Calculating Doses and Flow Rates and Administering Continuous Intravenous Infusions

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of aseptic technique is necessary.

• Nurses must be aware of the indications, actions, side effects, dosages, administration/storage, assessment, and evaluation for medications administered.

• Many different types of medications are delivered as continuous intravenous (IV) infusions in acute and critical care settings. These medications include, but are not limited to, vasoactive, inotropic, antidysrhythmic, sedative, and analgesic agents. Hemodynamic assessment and electrocardiographic (ECG) monitoring are frequently necessary to evaluate the patient’s response to the infusion. The nurse must be familiar with monitoring equipment such as cardiac monitors, arterial lines, pulmonary artery catheters, and noninvasive blood pressure cuffs.

• Titration is adjustment of the dose, either increasing or decreasing, to attain the desired patient response. Weaning is a gradual decrease of the dose when the medication is being discontinued.

• Alterations or interruptions of the flow rate can significantly affect the dose of medication being delivered and adversely affect the patient. For accurate delivery of IV medications, volume-controlled infusion devices are required

• “Smart technologies” are electronic devices, such as computers, bedside monitors, and infusion pumps, that perform calculations of doses and flow rates after information is entered and programmed by the user. Although these devices are not universally available, their use may help to reduce medication errors.4

• Smart pumps are infusion pumps with comprehensive libraries of drugs and dose calculation software that can perform a “test of reasonableness” to check that programming is within preestablished institutional limits before the infusion can begin, which can reduce medication errors, improve workflow, and provide a source of data for continuous quality improvement.10

• Use of smart infusion pumps with activated dosage error reduction software alerts the practitioner when safe doses and infusion rates have been exceeded.7 The clinician must use the technology consistently to avoid serious medication infusion errors.6

• Be aware that double key bounce and double keying errors may occur when pressing a number key once on an infusion pump, resulting in the unintended consequence of a repeat of that same number. This can result in infusing medications at a higher rate than expected.5

• Three factors are involved in the calculations for continuous IV infusions:

The concentration is the amount of medication diluted in a given volume of IV solution (e.g., 400 mg dopamine diluted in 250 mL normal saline [NS] solution, resulting in a concentration of 1.6 mg/mL; or 2 g lidocaine diluted in 500 mL 5% dextrose in water [D5W], yielding a concentration of 4 mg/mL). The concentration is also expressed as amount of medication per milliliter of fluid.

The concentration is the amount of medication diluted in a given volume of IV solution (e.g., 400 mg dopamine diluted in 250 mL normal saline [NS] solution, resulting in a concentration of 1.6 mg/mL; or 2 g lidocaine diluted in 500 mL 5% dextrose in water [D5W], yielding a concentration of 4 mg/mL). The concentration is also expressed as amount of medication per milliliter of fluid.

The dose of the medication is the amount of medication to be administered over a certain length of time (e.g., dopamine 5 mcg/kg/min, lidocaine 2 mg/min, or diltiazem 5 mg/hr). The units of measure for the dose differ for various medications. The length of time is 1 minute or 1 hour. If the medication is weight-based, the dose of the medication is per kilogram of patient weight.

The dose of the medication is the amount of medication to be administered over a certain length of time (e.g., dopamine 5 mcg/kg/min, lidocaine 2 mg/min, or diltiazem 5 mg/hr). The units of measure for the dose differ for various medications. The length of time is 1 minute or 1 hour. If the medication is weight-based, the dose of the medication is per kilogram of patient weight.

The flow rate is the rate of delivery of the IV fluid solution expressed as volume of IV fluid delivered per unit of time (e.g., 20 mL/hr). The unit of measure of the flow rate is milliliter per hour.

The flow rate is the rate of delivery of the IV fluid solution expressed as volume of IV fluid delivered per unit of time (e.g., 20 mL/hr). The unit of measure of the flow rate is milliliter per hour.

• All units of measure in the formula must be the same. It frequently is necessary to perform some conversions on the concentration before entering it into the formula. The units of measure of the concentration must be converted to the same units of measure of the dose (e.g., the concentration of dopamine is measured in milligrams, but the dose of dopamine is measured in micrograms).

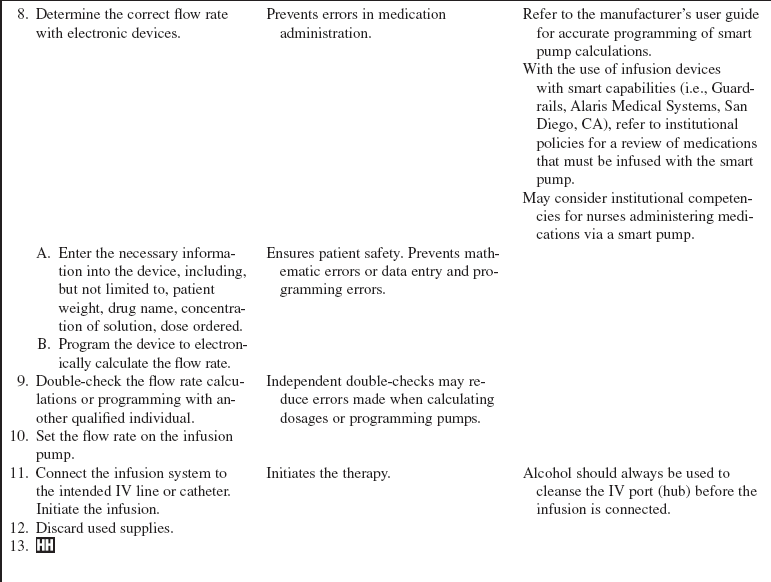

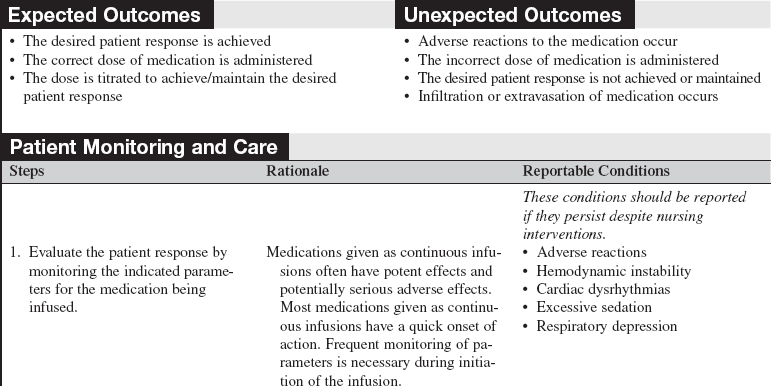

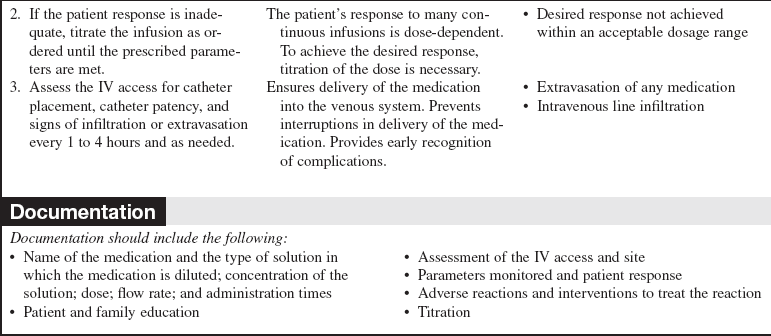

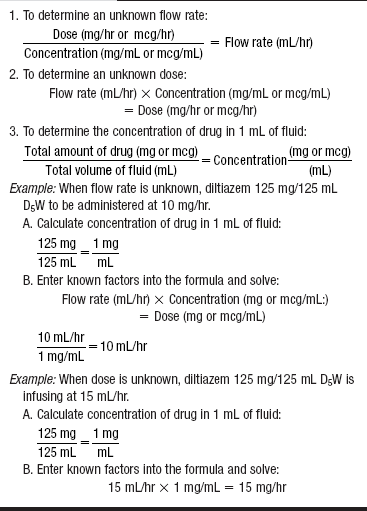

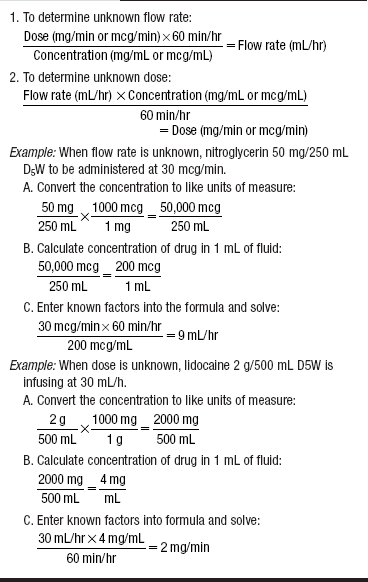

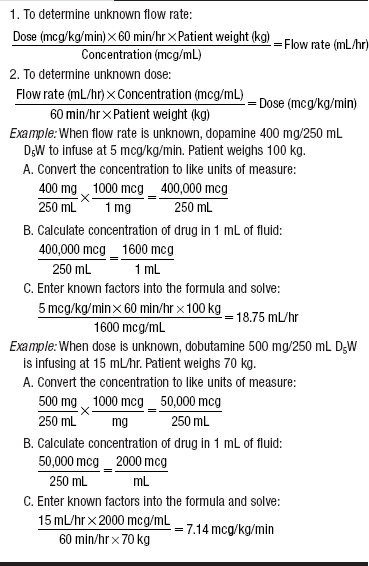

• The mathematic formula for continuous IV infusion contains the three factors involved in continuous infusion (Table 139-1). When two factors are known, the third can be calculated with the basic formula. Therefore, when the concentration of the solution and the prescribed dose are known, the flow rate can be determined. When the concentration of the solution and the flow rate are known, the dose can be determined. Variations on the basic formula are used to allow for medications delivered per hour or per minute and for medications that are weight-based (Tables 139-2 and 139-3).

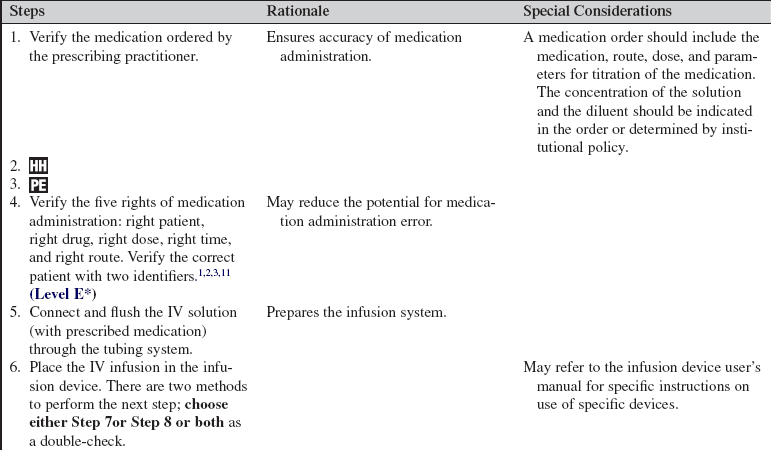

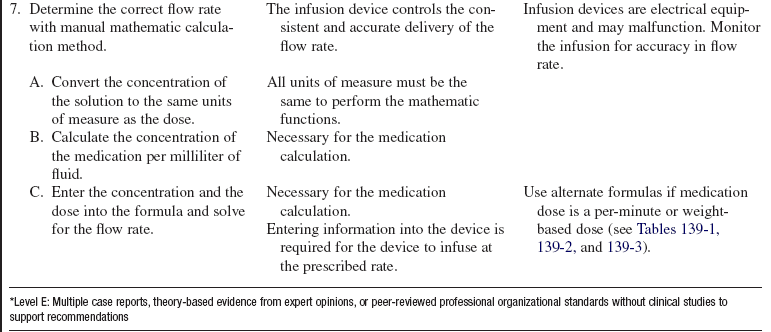

Table 139-1

*Because there are units on the top of the equation and units on the bottom of the equation, to ensure that the final units are correct, the units on the bottom of the equation must be inverted and multiplied by the units of the top of the equation.

Table 139-2

Variation for Medication Doses Measured per Minute (mg/min or mcg/min)*

*The time factor of 60 min/hr must be added to the basic formula.

Table 139-3

Variation for Weight-Based Medication Doses Measured per Minute (mcg/kg/min)*

*The patient’s weight in kilograms and the time factor of 60 min/hr must be added to the basic formula.

• Calculations for weight-based medications include the patient’s weight in the formula. The choice of which weight to use can be challenging. Much disagreement and inconsistency are found in the literature as to which weight to use, ideal body weight, actual body weight, or dry body weight.2,7 Distribution of specific medications across fat and fluid body compartments varies, thus affecting the therapeutic level. Because most medications are titrated to patient response and a desired clinical end point, a consistent approach is to use the patient’s admission weight for initial dose calculations. The clinical pharmacist then should be consulted for obese patients and for medications that have potentially dangerous toxicities.

• Central IV access should be used for vasoconstrictive medications and medications that can cause tissue damage when extravasated.3 Mechanisms and agents that may cause tissue damage include osmotic damage from hyperosmolar solutions, ischemic necrosis caused by vasoconstrictors and certain cation solutions, direct cellular toxicity caused by antineoplastic agents, direct tissue damage from pH strong acids and bases, and direct irritation.9

• The Joint Commission goal for medication safety includes standardization and limiting the number of drug concentrations available in organizations.11 Standardized dosing methods for the same medications reduce IV infusion errors.7

• The Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHI) recommendations for IV medication safety include conducting independent double checks, dose calculation aids on IV solution bag labels, use of IV smart infusion pumps with safety features, and use of premade dose and flow-rate charts.1

• Another recommendation identified the positive impact of regular drug administration updates and formal arithmetic testing on the frequency and cause of medication errors that are the result of lack of ability to calculate drug dosage correctly.8

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the indications and expected response to the pharmacologic therapy.  Rationale: Patients and families need explanations of the plan of care and interventions.

Rationale: Patients and families need explanations of the plan of care and interventions.

• Instruct the patient to report adverse symptoms, as indicated. Reportable symptoms include, but are not limited to, pain, burning, itching, or swelling at the IV site; dizziness; shortness of breath; palpitations; and chest pain.  Rationale: Reporting assists the nurse to evaluate the response to the pharmacologic therapy and to identify adverse reactions.

Rationale: Reporting assists the nurse to evaluate the response to the pharmacologic therapy and to identify adverse reactions.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess medication allergies.  Rationale: Assessment provides identification and prevention of allergic reactions.

Rationale: Assessment provides identification and prevention of allergic reactions.

• Obtain vital signs and hemodynamic parameters.  Rationale: The need for vasoactive agents is established, and baseline data are provided to evaluate the response to therapy.

Rationale: The need for vasoactive agents is established, and baseline data are provided to evaluate the response to therapy.

• Assess the ECG results.  Rationale: Assessment establishes the need for antidysrhythmic therapy and provides baseline data.

Rationale: Assessment establishes the need for antidysrhythmic therapy and provides baseline data.

• Obtain other assessments relevant to the medication being administered (e.g., sedation scale for continuous IV sedatives).  Rationale: Patients are assessed for specific parameters that are affected by various medications in order to note the efficacy of the medications and to ensure their safe delivery.2

Rationale: Patients are assessed for specific parameters that are affected by various medications in order to note the efficacy of the medications and to ensure their safe delivery.2

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Weigh the patient, if the medication is weight-based.  Rationale: Calculation of the correct dose based on patient weight is permitted. If the patient’s weight has changed during hospitalization because of edema or other causes, use of the baseline admission weight is preferable.

Rationale: Calculation of the correct dose based on patient weight is permitted. If the patient’s weight has changed during hospitalization because of edema or other causes, use of the baseline admission weight is preferable.

• Verify patency or obtain patent, appropriate IV access.  Rationale: Delivery of the medication into the IV space is ensured. Some continuous infusion medications require central line access to prevent irritation or damage to smaller peripheral veins and to reduce the risk for extravasation.

Rationale: Delivery of the medication into the IV space is ensured. Some continuous infusion medications require central line access to prevent irritation or damage to smaller peripheral veins and to reduce the risk for extravasation.

References

1. Crimlisk, J, Johnstone, D, Sanchez, G, Evidence-based practice, clinical simulations workshop, and intravenous medications. moving toward safer practice. Med Surg Nurs. 2009; 18(3):153–160.

2. Deglin, JH, Vallerand, AH. Davis’s drug guide for nurses, ed 11. Philadelphia: F. A. Davis Co; 2009.

3. Ekle E. &, Sibley A, eds. Nurses handbook of IV drugs, ed 3, Sudbury, MA: Jones & Bartlett -Publishers, 2009.

![]() 4. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), Medication safety alert. smart infusion pumps join CPOE and bar coding as important ways to prevent medications errors. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Huntington Valley, PA, 2002.

4. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), Medication safety alert. smart infusion pumps join CPOE and bar coding as important ways to prevent medications errors. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Huntington Valley, PA, 2002.

5. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), Medication safety alert nurse advise. ERRdouble key bounce and double keying errors. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Huntington Valley, PA, 2006.

6. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP). Smart pumps are not smart on their own. ISMP Medication Safety Alert. 2007; 12(8):1–2.

7. Institute for Safe Medication Practices (ISMP), Medication safety alert nurse advise. ERRlack of standard dosing methods contributes to IV infusion errors,. Institute for Safe Medication Practices, Huntington Valley, PA, 2008.

8. Pentin, J, Smith, J, Drug calculations. are they safer with or without a calculator. Br J Nurs. 2006; 15(14):778–781.

9. Polovich M, Whitford JM, Olsen M, eds. Chemotherapy and biotherapy guidelines and recommendations for practice, ed 3, Pittsburgh: ONS Publishing, 2009.

![]() 10. Reves, JG. “Smart pump” technology reduces errors, 2003. http://www.apsf.org/resource_center/newsletter/2003/spring/smartpump.htm, July 28, 2009. [retrieved].

10. Reves, JG. “Smart pump” technology reduces errors, 2003. http://www.apsf.org/resource_center/newsletter/2003/spring/smartpump.htm, July 28, 2009. [retrieved].

11. Spratto G, Woods A, eds.. 2008 PDR nurse’s drug handbook. patient safety goals [appendix 12]. Thompson Healthcare Inc and Delmar Learning: Clifton Park, NY, 2008.

![]() Guiliano, K, et al. A new strategy for calculating medication infusion rates. Crit Care Nurs. 1993; 13:77–82.

Guiliano, K, et al. A new strategy for calculating medication infusion rates. Crit Care Nurs. 1993; 13:77–82.

![]() Hadaway, LC. How to safeguard delivery of high-alert IV drugs. Nursing. 2001; 31:36–42.

Hadaway, LC. How to safeguard delivery of high-alert IV drugs. Nursing. 2001; 31:36–42.

![]() Keohane, C, Hayes, J, Saniuk, C, et al. Intravenous medication safety and smart infusion systems. J Infusion Nurs. 2005; 28(5):321–328.

Keohane, C, Hayes, J, Saniuk, C, et al. Intravenous medication safety and smart infusion systems. J Infusion Nurs. 2005; 28(5):321–328.

![]() McMillen, P. Calculating medication dosages. Crit Care Nurs. 2000; 20:17–19.

McMillen, P. Calculating medication dosages. Crit Care Nurs. 2000; 20:17–19.

![]() Shilling, McCann, JA. executive publisherSpringhouse’s dosage calculations made incredibly easy, ed 2. Springhouse, PA: Springhouse; 2000.

Shilling, McCann, JA. executive publisherSpringhouse’s dosage calculations made incredibly easy, ed 2. Springhouse, PA: Springhouse; 2000.