Withholding and Withdrawing Life-Sustaining Therapy

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Withholding life-sustaining therapy (LST) is defined as “the considered decision not to institute a medically appropriate and potentially beneficial therapy, with the understanding that the patients will probably die without the therapy in question.”10

• Withdrawal of LST is defined as “the cessation and removal of an ongoing medical therapy with the explicit intent not to substitute an equivalent alternative treatment; it is fully anticipated that the patient will die following the change in therapy.”10

• Knowledge of state regulations, and hospital policies or procedures, regarding end-of-life decision making is essential.

• Hospitals should have policies that direct the process to withhold and withdraw LST.

• As much information as possible should be obtained from the patient regarding preferences about LST.

• If the patient is unable to communicate or chooses not to communicate, information should be obtained from the patient’s designated surrogate, family, or healthcare providers regarding the patient’s desired wishes about LST. This information may be ascertained from an advance directive or from verbal conversations with the surrogate, family, friends, or healthcare providers.

• Advance directives may exist in the form of a living will or a healthcare proxy.

A living will is a document that identifies treatments a patient would or would not want under specific end-of-life situations. Most are specific to terminal illness, permanent state of unconsciousness, or persistent vegetative state.

A living will is a document that identifies treatments a patient would or would not want under specific end-of-life situations. Most are specific to terminal illness, permanent state of unconsciousness, or persistent vegetative state.

A healthcare proxy or a durable power of attorney for healthcare is a document that identifies a predetermined person who has been given the authority to represent the patient’s preferences in healthcare decision making if the patient is unable to make decisions (e.g., comatose state) or chooses not to participate.

A healthcare proxy or a durable power of attorney for healthcare is a document that identifies a predetermined person who has been given the authority to represent the patient’s preferences in healthcare decision making if the patient is unable to make decisions (e.g., comatose state) or chooses not to participate.

• Some patients have letters or other informal documents in which they convey their preferences for factors that should affect decision making and identify someone who can represent their wishes in decision making.

• Patients have a moral and legal right and responsibility to make decisions about their healthcare and the use of LST.

• Decision-making capacity is determined by an individual’s ability to2:

• If a patient no longer has decision-making capacity, the patient’s preferences should be represented by the patient’s healthcare proxy. The ideal proxy, even if not specified within a legal framework, is the person who can represent the patient’s wishes, not the surrogate’s. That is, decisions made by the healthcare proxy or surrogate should be based on the patient’s previously stated wishes or, if there were no specific statements on presumed preferences, based on lifestyle and prior choices.

• Usually the patient’s family is involved in the process of withholding and withdrawing LST. On occasion, the patient prefers that the family not be involved. If the patient does not want the family to be involved, the healthcare team should work with the patient to identify another person who can serve as the healthcare proxy or surrogate in the event that the patient loses decision-making capacity.

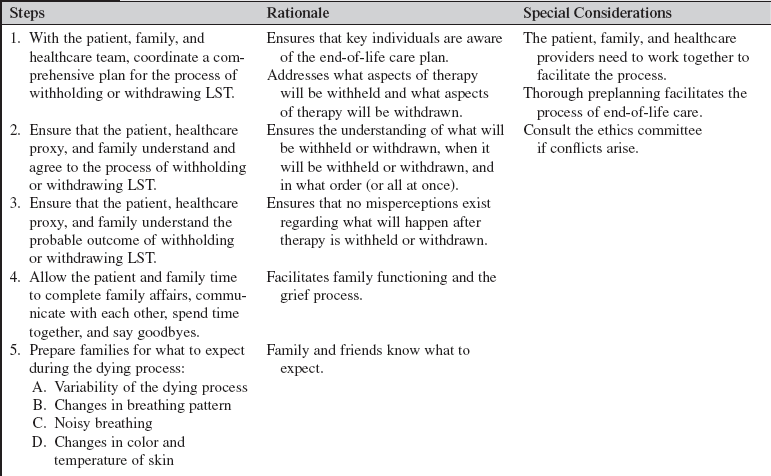

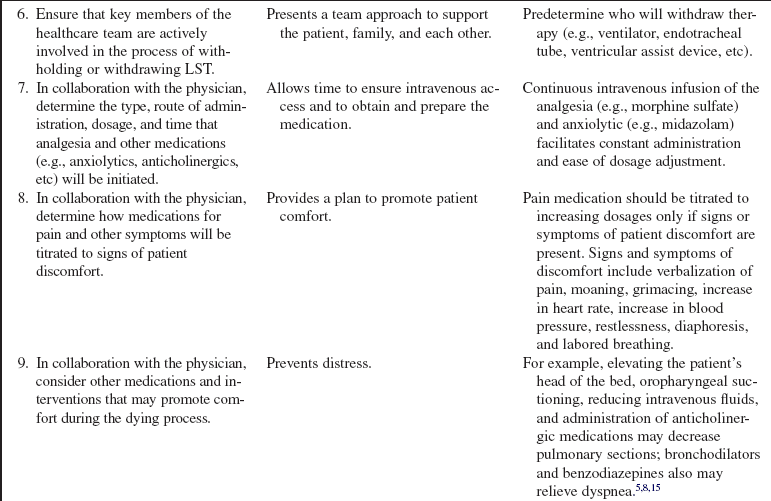

• Dialogue regarding end-of-life care should be comprehensive. Discussions should include the healthcare team, the patient, and the patient’s family. Discussions should include what treatments are going to be withheld or withdrawn and should focus on patient wishes and medically appropriate goals of care. If the goal of care is a peaceful death, then all therapies that do not contribute toward this goal should be considered for discontinuation, including cessation of vasoactive agents, ventilatory therapy, assist devices, implantable cardioverter-defibrillator therapy, intravenous fluids, nutrition, laboratory studies, radiographs, extubation, etc.

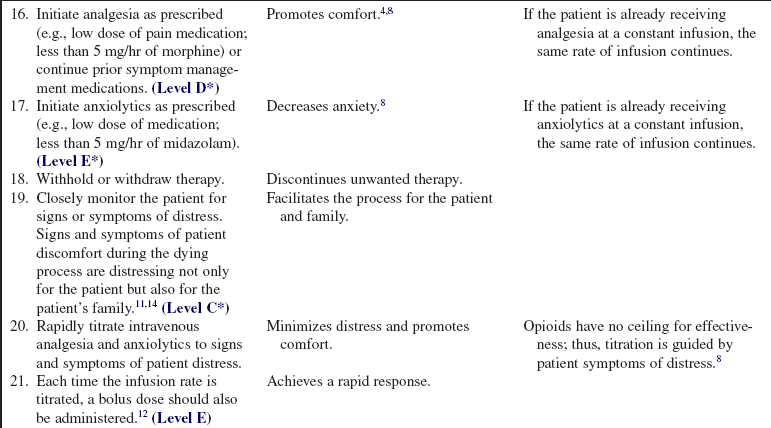

• Therapies that support the goal of a peaceful death should be continued, such as administration of analgesia to promote comfort and anxiolytics to decrease anxiety.

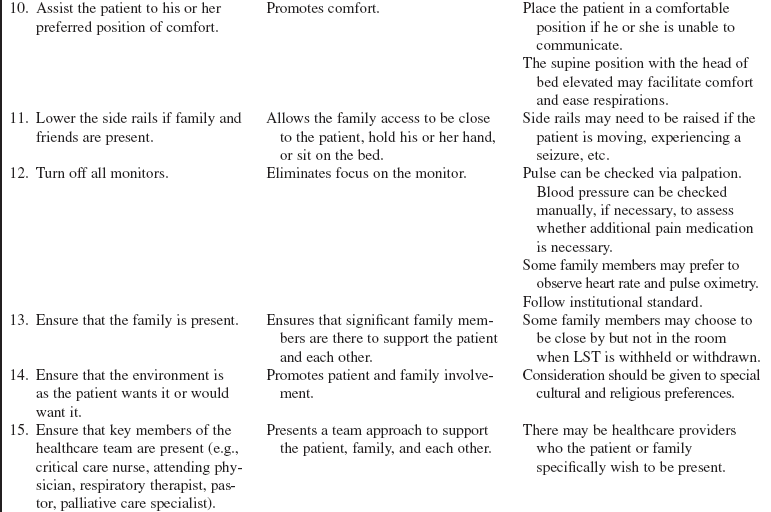

• Patient comfort should also be promoted by ensuring a comfortable position, frequent skin and mouth care, and interventions to relieve signs and symptoms of distress.

• Families need to be supported throughout the end-of-life decision-making process.

• Families should be encouraged to say final goodbyes and to be present should they desire during the dying process.

• Patients, families, and healthcare providers often have different values.

• Healthcare providers are responsible for knowing how their personal beliefs affect their interactions with patients, families, and other healthcare providers.

• Patients and their families should be actively involved in all healthcare decisions, including end-of-life decisions (unless the patient requests that family members not be involved; see previous discussion).

• Family members involved in end-of-life decision making should be guided by their knowledge of what the patient wants or would want.

• If a critical care nurse cannot support the patient and family in the process of withholding or withdrawing LST, the critical care nurse should proceed through the appropriate channels to transfer care to another critical care nurse.

• It is recommended that paralyzing agents are discontinued and cleared from the patient’s body before withdrawal of LST.13

• Maintenance of patient dignity and comfort is essential at all times, and especially at the end of life.

• Opioid administration to treat pain rarely causes respiratory depression when carefully titrated to a patient’s distress.3,7

• Nurses should use effective doses of medications prescribed for symptom control; nurses have a moral obligation to advocate on behalf of the patient when prescribed medications are not sufficient to manage distressing symptoms.1

• Uncontrolled pain should be considered an emergency, with the entire healthcare team taking responsibility to provide relief.6

• Family meetings can be helpful in aiding patients, families, and healthcare providers in planning end-of-life care.

• Palliative care is interdisciplinary care that aims to relieve suffering and improve quality of life for patients with serious illness and their families.9 Palliative care should be integrated into the care of acutely ill or injured patients in the intensive care unit (ICU).15

• Hospital ethics committees can be helpful in aiding patients, families, and healthcare providers when conflicts arise with decision making or during withholding or withdrawing LST discussions.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• In collaboration with the physician and the critical care team, inform the patient and family of the patient’s current condition and prognosis.  Rationale: The patient and family are informed of and prepared for anticipated outcomes.

Rationale: The patient and family are informed of and prepared for anticipated outcomes.

• Explain resources available to aid with end-of-life decision making (e.g., nurses, physicians, social workers, pastoral care, grief counselors, palliative care team, ethics consultation, ethics committee).  Rationale: Additional resources and support are offered to assist the patient or family with end-of-life decisions.

Rationale: Additional resources and support are offered to assist the patient or family with end-of-life decisions.

• Describe how the patient is likely to respond to withholding or withdrawing of therapies, including expected outcomes and unexpected outcomes.  Rationale: The patient and family are prepared for the process. If death is anticipated, the dying process may progress quickly or slowly (e.g., occurring within minutes or lasting days). Although rare, death may not ensue after LST is withheld or withdrawn.

Rationale: The patient and family are prepared for the process. If death is anticipated, the dying process may progress quickly or slowly (e.g., occurring within minutes or lasting days). Although rare, death may not ensue after LST is withheld or withdrawn.

• Explain that analgesia and anxiolytics will be administered before withholding or withdrawing LST to prevent discomfort and after withholding or withdrawing LST to relieve any signs or symptoms of discomfort.  Rationale: Patient and family anxiety is decreased with the knowledge that patient comfort will be promoted.

Rationale: Patient and family anxiety is decreased with the knowledge that patient comfort will be promoted.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assist the physician or advanced practice nurse in assessment of the patient’s decision-making capacity.  Rationale: Patients with decision-making capacity should make their own therapy decisions.

Rationale: Patients with decision-making capacity should make their own therapy decisions.

• If patients do not have decision-making capacity, determine whether the patient has a designated healthcare proxy or surrogate.  Rationale: The patient’s healthcare proxy should make decisions for the patient if he or she no longer has decision-making capacity.

Rationale: The patient’s healthcare proxy should make decisions for the patient if he or she no longer has decision-making capacity.

• If patients do not have decision-making capacity or a healthcare proxy, identify key individuals who can best represent patient preferences and who will be active participants in therapy decisions.  Rationale: Family members must be able to communicate patient wishes for end-of-life care or be able to determine to the best of their knowledge what therapies the patient would or would not want. The patient may also have communicated therapy wishes to primary care providers and friends.

Rationale: Family members must be able to communicate patient wishes for end-of-life care or be able to determine to the best of their knowledge what therapies the patient would or would not want. The patient may also have communicated therapy wishes to primary care providers and friends.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Collaborate with the patient and family to plan the day and time that LST will be withheld or withdrawn.  Rationale: Family and friends have time to spend with the patient and to arrive from out of town. The healthcare team has time to plan availability to be present during therapy changes.

Rationale: Family and friends have time to spend with the patient and to arrive from out of town. The healthcare team has time to plan availability to be present during therapy changes.

• Identify family or friends whom the patient and family would like present during the withholding or withdrawal process.  Rationale: The patient and family are involved in planning of the withholding or withdrawal of therapy, and patient preferences are respected.

Rationale: The patient and family are involved in planning of the withholding or withdrawal of therapy, and patient preferences are respected.

• In addition to nursing, medicine, and possibly respiratory therapy, identify additional members of the healthcare team who the patient or family would like present during the withholding or withdrawal process (e.g., clergy, social worker, palliative care specialist, grief counselor).  Rationale: The patient and family are provided control as they determine essential members of the healthcare team who should be involved with the withholding or withdrawing of therapy process.

Rationale: The patient and family are provided control as they determine essential members of the healthcare team who should be involved with the withholding or withdrawing of therapy process.

• Encourage the patient and family to personalize the environment by bringing in music or other items that will make the room as the patient would want it to be.  Rationale: An individualized, peaceful, caring environment is promoted.

Rationale: An individualized, peaceful, caring environment is promoted.

• Establish or maintain a patent intravenous access.  Rationale: Intravenous access is necessary for administration of analgesia and anxiolytics.

Rationale: Intravenous access is necessary for administration of analgesia and anxiolytics.

References

![]() 1. American Nurses Association, American Nurses Association position statement on pain management and control of distressing symptoms in dying patients . ANA, Washington, DC, 2003.

1. American Nurses Association, American Nurses Association position statement on pain management and control of distressing symptoms in dying patients . ANA, Washington, DC, 2003.

![]() 2. Beauchamp, TL, Childress, JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, ed 5. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

2. Beauchamp, TL, Childress, JF. Principles of biomedical ethics, ed 5. New York: Oxford University Press; 2001.

3. Campbell, ML, Treating distress at the end of life. the principle of double effect. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2008; 19(3):340–344.

![]() 4. Campbell, ML, Bizek, KS, Thill, MC, Patient responses during rapid terminal weaning from mechanical ventilation. a prospective study. Crit Care Med 1999; 27:73–77.

4. Campbell, ML, Bizek, KS, Thill, MC, Patient responses during rapid terminal weaning from mechanical ventilation. a prospective study. Crit Care Med 1999; 27:73–77.

5. Clark, K, Butler, M. Noisy respiratory secretions at the end of life. Curr Opin Support Palliat Care. 2009; 3(2):120–124.

6. Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, HPNA position statement. pain management . HPNA, Pittsburgh, 2008.

7. Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, HPNA position statement. the ethics of opiate use within palliative care . HPNA, Pittsburgh, 2008.

8. Medina, J, Puntillo, K, AACN protocols for practice . palliative care and end-of-life issues in critical care . Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, MA, 2006.

9. National Consensus Project for Quality Palliative Care. ed 2. Clinical practice guidelines for quality palliative care, Pittsburgh, 2009.

![]() 10. Prendergast, TJ, Claessens, MT, Luce, JM. A national survey of end-of-life care for critically ill patients. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1998; 158:1163–1167.

10. Prendergast, TJ, Claessens, MT, Luce, JM. A national survey of end-of-life care for critically ill patients. Am J Resp Crit Care Med. 1998; 158:1163–1167.

![]() 11. Tolle, SW, et al. Families reports of barriers to optimal care of the dying. Nurs Res. 2000; 49(6):310–317.

11. Tolle, SW, et al. Families reports of barriers to optimal care of the dying. Nurs Res. 2000; 49(6):310–317.

12. Truog, RD, Campbell, ML, Curtis, JR, et al, Recommendations for end-of-life care in the intensive care unit. a consensus statement by the American College of Critical Care Medicine. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36(3):953–963.

![]() 13. Truog, RD, Burns, JP, Mitchell, C, et al. Pharmacologic paralysis and withdrawal of mechanical ventilation at the end of life. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342(7):508–511.

13. Truog, RD, Burns, JP, Mitchell, C, et al. Pharmacologic paralysis and withdrawal of mechanical ventilation at the end of life. N Engl J Med. 2000; 342(7):508–511.

14. Wiegand DL, Petri L : Is a good death possible after withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy ? Crit Care Clin North Am. In press

15. Wiegand, DL, Williams, LD. End-of-life care. In: Carlson K, ed. AACN advanced critical care nursing. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009:1507–1525.

16. Wiegand, DL, Withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy after sudden, unexpected life-threatening illness or injury . interactions between patients’ families, healthcare providers, and the healthcare system. Am J Crit Care. 2006; 15(2):178–187.

![]() Ballentine, JM, Pacemaker and defibrillator deactivation in competent hospice patients. an ethical consideration. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2005; 22:14–19.

Ballentine, JM, Pacemaker and defibrillator deactivation in competent hospice patients. an ethical consideration. Am J Hosp Palliat Med 2005; 22:14–19.

![]() Braun, TC, Hagen, NA, Hatfield, RE, et al. Cardiac defibrillators in terminal care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999; 18:126–131.

Braun, TC, Hagen, NA, Hatfield, RE, et al. Cardiac defibrillators in terminal care. J Pain Symptom Manage. 1999; 18:126–131.

Campbell, ML. Terminal dyspnea and respiratory distress. Crit Care Clin North Am. 2004; 20:403–417.

Campbell, ML, Forgoing life-sustaining therapy . AACN, Laguna Niguel, CA, 1998.

Daly, BJ, Thomas, D, Dyer, MA. Procedures used in withdrawal of mechanical ventilation. Am J Crit Care. 1996; 5(5):331–338.

Dudzinski, DM. Ethics guidelines for destination therapy. Ann Thorac Surg. 2006; 81:1185–1188.

Goldstein, NE, Lampert, R, Bradley, E, et al. Management of implantable cardioverter defibrillators in end-of-life care. Ann Intern Med. 2004; 141:835.

Grassman, D. EOL considerations in defibrillator deactivation. Am J Hospice Palliat Med. 2005; 22:179–180.

The Hastings Center, Guidelines on the termination of life sustaining treatment and the care of the dying . University Press, Bloomington, IN, 1987.

Hospice and Palliative Nurses Association, HPNA position statement. withholding and/or withdrawing life sustaining therapies,. HPNA, Pittsburgh, 2008.

Lampert R, et al : HRS expert consensus statement on the management of Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Devices (CIEDs) in patients nearing end of life or requesting withdrawal of therapy. ( In Press ). Heart Rhythm.

Lewis, WR, Luebke, DL, Johnson, NJ, et al. Withdrawing implantable defibrillator shock therapy in terminally ill patients. Am J Med. 2006; 119:892.

Mayer, SA, Kossoff, SB. Withdrawal of life support in the neurological intensive care unit. Neurology. 1999; 52(8):1602–1609.

Nambisan, V, Chao, D, Dying and defibrillation. a shocking experience. Palliat Med 2004; 18:482–483.

President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research, Deciding to forego life-sustaining treatment. a report on the ethical medical, and legal issues in treatment decisions. US Government Printing Office, Washington DC, 1983.

MacIver, J, Ross, HJ. Withdrawal of ventricular assist device support. J Palliat Care. 2006; 21:151–156.

Morreim, EH, Surgically implanted devices. ethical challenges in a very different kind of research. Thorac Surg Clin 2005; 15:555–563.

Pellegrino, ED, Decisions to withdraw life-sustaining treatment. a moral algorithm. JAMA 2000; 283:1065–1067.

Tilden, VP, Tolle, SW, Nelson, CA, et al. Family decision making in foregoing life-extending treatments. J Family Nurs. 1999; 5:426–442.

Tilden, VP, Tolle, SW, Garland, MJ, et al, Decisions about life sustaining treatment. impact of physicians’ behavior on the family. Arch Intern Med. 1995; 155(6):633–638.

Wiegand, DL, In their own time. the family experience during the process of withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. J Palliat Med. 2008; 11(8):1115–1121.

Wiegand, DL, Deatrick, JA, Knafl, K. Family management styles related to withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy from adults who are acutely ill or injured. J Family Nurs. 2008; 14(1):16–32.

Wiegand, DL, Kalowes, PG. Withdrawal of cardiac medications and devices. AACN Adv Crit Care. 2007; 18(4):415–425.

Wiegand, DL, Families and withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy. state of the science. J Family Nurs. 2006; 12(2):165–184.