Donation After Cardiac Death

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

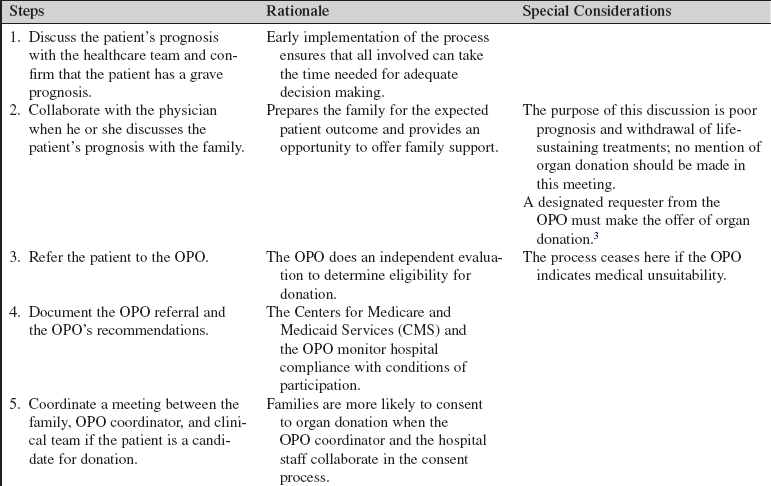

• Knowledge is needed of federal rules, state laws, organ procurement organization (OPO) policies, and hospital policies regarding donation after cardiac death. In 2007, The Joint Commission required hospitals, in coordination with the OPO, to create either donation after cardiac death (DCD) policies or justifications for opting out.2,3

• DCD occurs after irreversible cessation of cardiopulmonary function (see Procedure135).

A patient is ventilator-dependent, and not brain dead, and decisions have been made to withdraw mechanical ventilation.

A patient is ventilator-dependent, and not brain dead, and decisions have been made to withdraw mechanical ventilation.

Patient meets OPO designation for suitability for donation.

Patient meets OPO designation for suitability for donation.

Cardiopulmonary death is likely to occur soon after withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (e.g., less than 90 minutes). The prescribed time interval may vary according to the transplant surgical team and organ.

Cardiopulmonary death is likely to occur soon after withdrawal of mechanical ventilation (e.g., less than 90 minutes). The prescribed time interval may vary according to the transplant surgical team and organ.

• Families of patients considered for donation after cardiac death are dealing only secondarily with the request for organ donation. First, these families are dealing with the severe injury or illness of the patient that may have occurred suddenly.

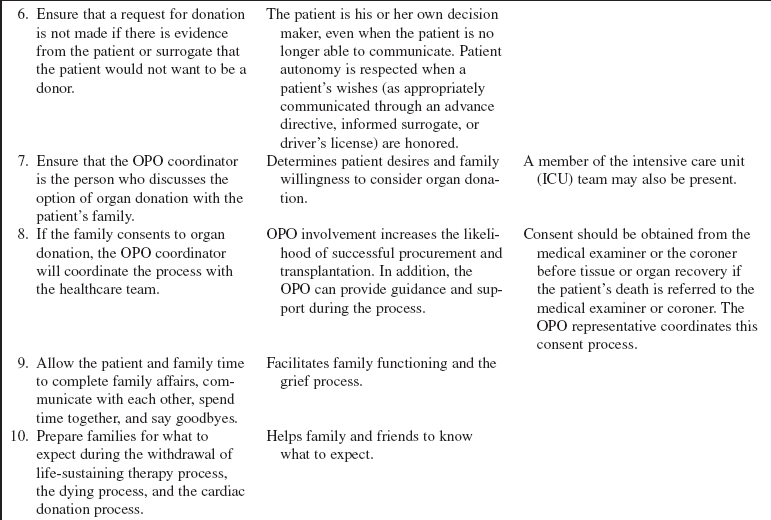

• The decision to cease prolonged measures, including mechanical ventilation, must occur before the discussion about donation after cardiac death.

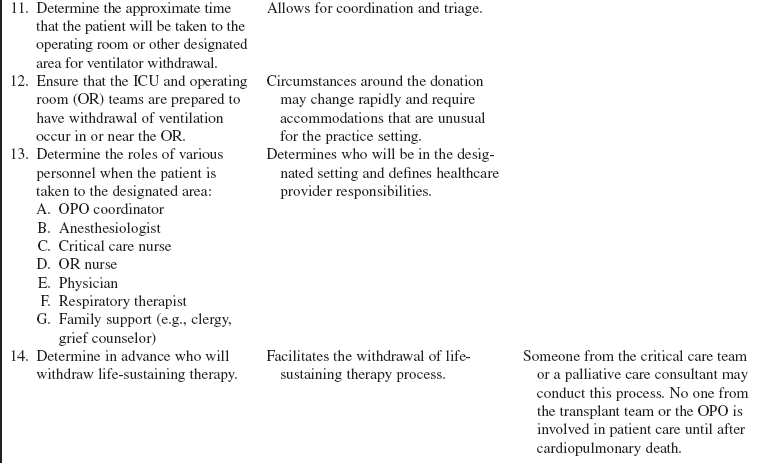

• The healthcare team that has cared for the potential donor must continue to care for the patient until cardiopulmonary death is pronounced.

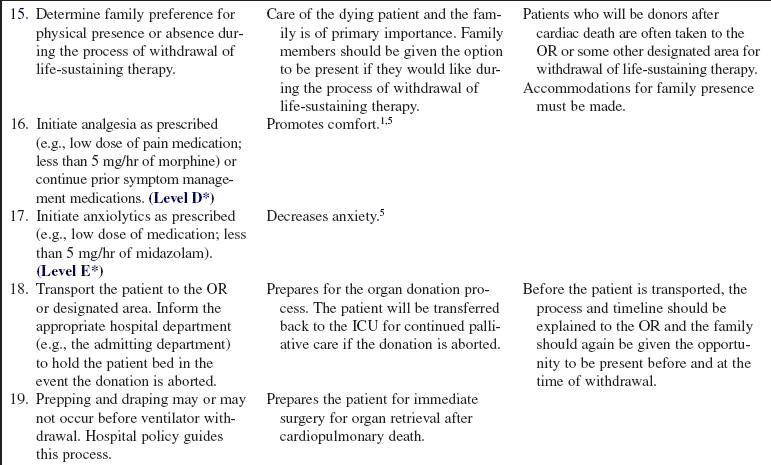

• Palliative care is the treatment goal of the potential donor until death is pronounced. A palliative care consultant, if available, may participate in the predeath processes.4

• Palliative care continues if the donation is aborted for any reason after ventilation is withdrawn (e.g., the patient’s death does not follow rapidly after ventilator withdrawal).

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Inform the family of the patient’s current condition.  Rationale: The family is kept informed and is prepared for realistic expectations about the patient’s expected outcome.

Rationale: The family is kept informed and is prepared for realistic expectations about the patient’s expected outcome.

• Explain the medical and nursing care provided to the patient.  Rationale: The family understands therapies provided to treat and support the patient.

Rationale: The family understands therapies provided to treat and support the patient.

• Introduce the OPO designated requester when it is time to request organ donation.  Rationale: Request for organ donation is the responsibility of representatives from the OPO or a specially trained designated hospital requester.3

Rationale: Request for organ donation is the responsibility of representatives from the OPO or a specially trained designated hospital requester.3

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• With the critical care team, ascertain who is the patient’s surrogate decision maker if the patient lacks capacity to make his or her own decisions.  Rationale: Hospital policy guides identification of the surrogate based on statute.

Rationale: Hospital policy guides identification of the surrogate based on statute.

• Review with the family the medical and social history of the patient, including current age, injuries, chronic diseases, surgical history, familial history, and social habits. Of particular interest is a history of renal disease, hypertension, diabetes mellitus, malignant disease, hepatitis, and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).  Rationale: This information is important so that the OPO transplant coordinator can assess the medical suitability of the patient for organ donation.

Rationale: This information is important so that the OPO transplant coordinator can assess the medical suitability of the patient for organ donation.

• Perform a physical assessment, with emphasis on old surgical scars, needle track marks, tattoos, body piercing, congenital anomalies, and injuries.  Rationale: These are indicators of physical conditions or social behaviors that may influence organ suitability for transplantation. Patients with recent tattoos and body piercings or fresh needle tracks are considered high risk and may not be accepted as a donor by the transplant team.

Rationale: These are indicators of physical conditions or social behaviors that may influence organ suitability for transplantation. Patients with recent tattoos and body piercings or fresh needle tracks are considered high risk and may not be accepted as a donor by the transplant team.

• Monitor pertinent patient data, including urine output, liver function studies, renal function studies, electrolytes, serum osmolality, coagulation panel, and urine studies, including specific gravity and culture results.  Rationale: Data are provided that may influence organ suitability for transplantation.

Rationale: Data are provided that may influence organ suitability for transplantation.

• Determine an accurate measurement of the patient’s height and weight.  Rationale: This information is important for matching organs to a recipient of a corresponding body size.

Rationale: This information is important for matching organs to a recipient of a corresponding body size.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the family understands preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed. Families need special emotional consideration during all counseling and teaching.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Refer patients with a potentially life-threatening illness or injury to the OPO as early as possible for evaluation as a potential organ donor. Specific criteria do not exist for referral, unlike the case with the brain-dead organ donor.  Rationale: The OPO coordinator can evaluate the patient, and the critical care nurse is provided with information about the patient’s potential as an organ donor.

Rationale: The OPO coordinator can evaluate the patient, and the critical care nurse is provided with information about the patient’s potential as an organ donor.

• Involve additional hospital resources (e.g., clergy, grief counselors, palliative care specialists).  Rationale: Additional family support is provided throughout the end of the life process. Pastoral care may offer additional insights into faith, hope, and encouragement to those who may be experiencing despondency, remorse, guilt, or anger at this time.

Rationale: Additional family support is provided throughout the end of the life process. Pastoral care may offer additional insights into faith, hope, and encouragement to those who may be experiencing despondency, remorse, guilt, or anger at this time.

References

![]() 1. Campbell, ML, Bizek, KS, Thill, MC, Patient responses during rapid terminal weaning from mechanical ventilation. a prospective study. Crit Care Med 1999; 27:73–77.

1. Campbell, ML, Bizek, KS, Thill, MC, Patient responses during rapid terminal weaning from mechanical ventilation. a prospective study. Crit Care Med 1999; 27:73–77.

2. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital conditions of participation about organ/tissue donation. www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/som107ap_a_hospitals.pdf, November 6, 2008. [retrieved].

3. Fidler, SA. Implementing donation after cardiac death protocols. J Health Life Sci Law. 2008; 2(1):123–125-149.

4. Kelso, CM, Lyckholm, LJ, Coyne, PJ, et al. Palliative care consultation in the process of organ donation after cardiac death. J Palliat Med. 2007; 10(1):118–126.

5. Medina, J, Puntillo, K, AACN protocols for practice. palliative care and end-of-life issues in critical care,. Jones and Bartlett Publishers, Sudbury, MA, 2006.

American College of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Recommendations for non-heart-beating organ donation. a position paper by the ethics committee. Crit Care Med 2001; 29:1826–1831.

Arnold, RM, Youngner, SJ, Time is of the essence. the pressing need for comprehensive non-heart-beating cadaveric donation policies. Transplant Proc 1995; 27:2913–2921.

D’Alessandro, AM, Hoffman, RM, Belzer, FO, Non-heart-beating donors. one response to the organ shortage. Transplantation Rev 1995; 9:168–176.

Edwards, JM, Hasz, RD, Robertson, AM, Non-heart-beating organ donation. process and review. AACN Clin Issues Crit Care 1999; 10:293–300.

Frader, J, Non-heart-beating organ donation. personal and institutional conflicts of interest. Kennedy Inst Ethics J 1993; 3:189–198.

Institute of Medicine, Potts, J, principal, investigator, Non-heart-beating organ transplantation. medical and ethics issues in procurement. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 1997.

Institute of Medicine, Non-heart-beating organ transplantation. practice and protocols. National Academy Press, Washington, DC, 2000.

Younger, SJ, Arnold, RM. Ethical, psychosocial, and public policy implications of procuring organs from non-heart-beating cadaver donors. JAMA. 1993; 269:2769–2774.

Van Norman GA, Another matter of life and death. what every anesthesiologist should know about the ethical, legal, and policy implications of the non-heart-beating cadaver organ donor. Anesthesiology 2003; 98:763–773.