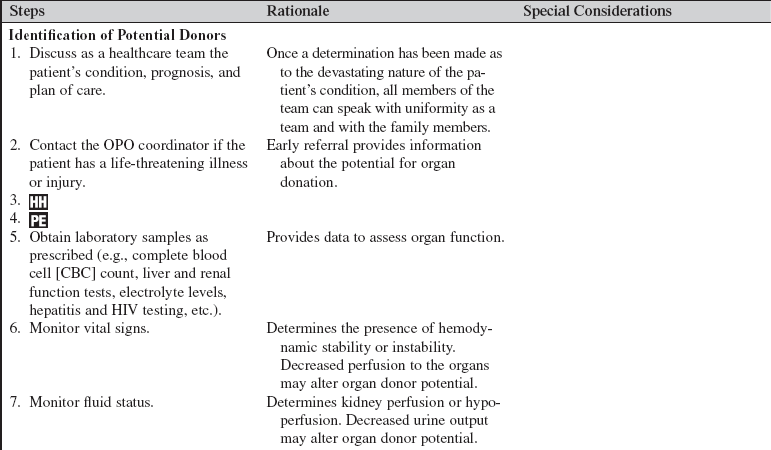

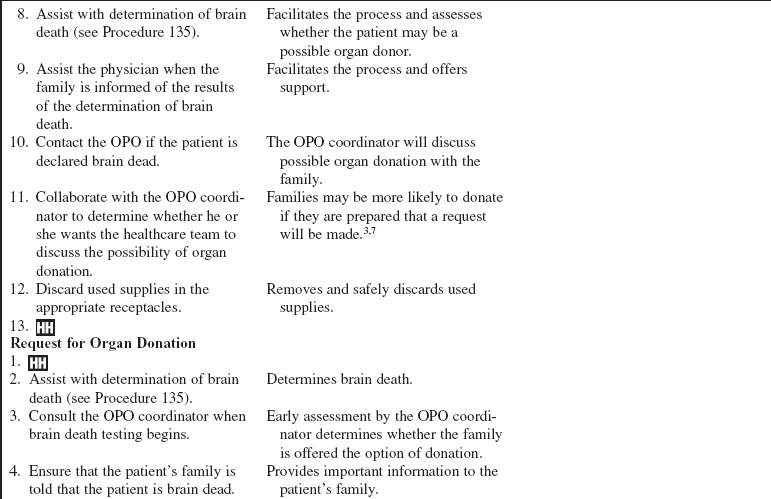

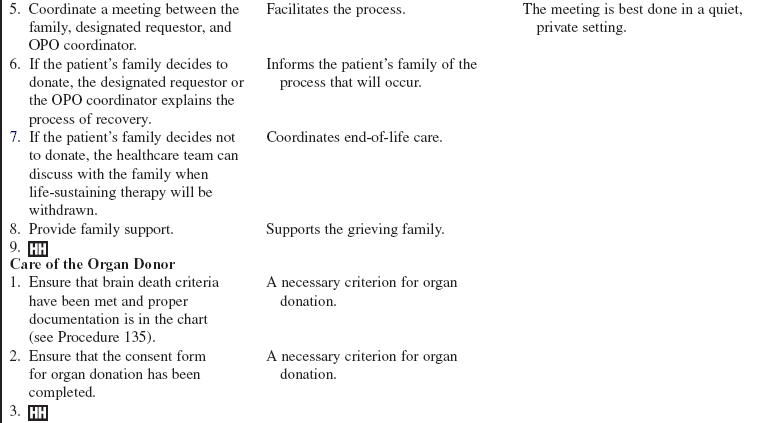

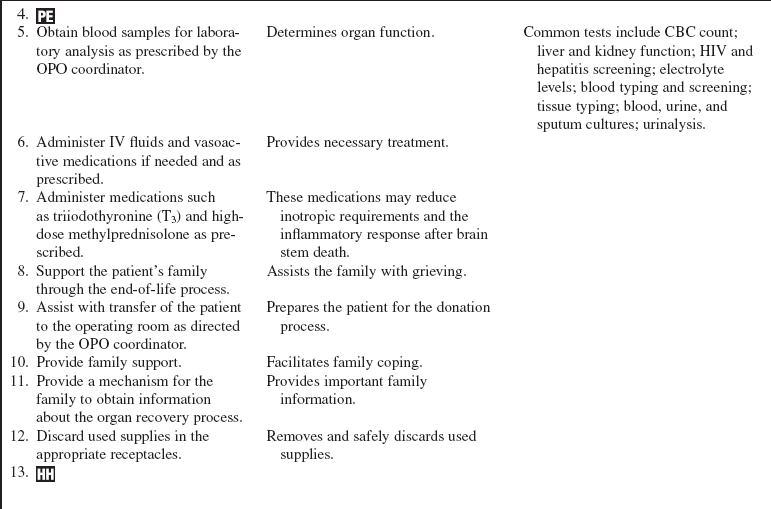

Organ Donation: Identification of Potential Organ Donors, Request for Organ Donation, and Care of the Organ Donor

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Organ transplantation continues to improve every year. This success has led to the situation in which the demand for organs is greater than the supply.4 From January 2009-January 2010, patients received 2,198 transplants. As of April 2010, there were 107,173 people on the waiting list.

• In 1968, the Uniform Anatomical Gift Act was created by the National Conference of Commissioners on Uniform State Laws. This document established a uniform Donor Card as a legal document for anyone 18 years or older to legally donate organs upon death.

• In 1980, the Uniform Determination of Death Act was passed into law; this act states that death may be declared with the cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or with irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem.

• In 1984, the National Organ Transplant Act established a nationwide computer registry operated by the United Network for Organ Sharing and authorized the funding of regional organ procurement organizations.

• As of 1998, every death or imminent death in a U.S. hospital must be reported to an organ procurement agency to meet the federal rules of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services.8

• In 2005, the Organ Donation and Recovery Improvement Act provided additional funding for individuals making living donations, funded research to increase public awareness of the donation process, and funded programs to increase hospital donation activities.

• The two types of donors are heart-beating and non–heart-beating donors.

• Heart-beating donation occurs when an individual has sustained a devastating intracranial catastrophe that results in the death of all neurologic functioning, including the brain stem. After two independent neurologic examinations are passed, an individual is declared legally dead and can be considered for potential organ donation. These patients are the single largest source of transplantable organs.10

• Donation after cardiac death or non–heart-beating donation can be considered after a number of devastating illnesses or injuries that can be classified on the basis of the Maastricht classification.1,2 Donation after cardiac death is a decision that can be made for a patient having life-sustaining therapy withdrawn. The patient is assessed to determine if he or she is a potential organ donor, and the family is approached for consent by an independent team of healthcare providers (not the recovery team of healthcare providers). After the family has consented and said their final goodbyes, the withdrawal of life-sustaining therapy process occurs. After a predefined period of asystole, usually 2 to 5 minutes, the patient is pronounced dead by an independent physician and the organ recovery process is initiated (see Procedures 135 and 137).

• The Joint Commission has a set of standards specific to organ procurement and hospital policies and procedures and their relationship to the regional Organ Procurement Organization (OPO).5,6

• Various legal documents (i.e., advance directives, wills, and driver licenses) direct all those involved as to the wishes of the individual to donate. Most OPOs recognize the obligation to maximize the recovery of organs for the benefit of those recipients awaiting life-saving transplantation; however, the implementation of this process should be accomplished in a respectful manner that honors the donor’s wishes. This process must include an approach that provides continuing support and care for the family while guiding them toward an understanding of their loved one’s wishes.7

• The patient remains in the critical care unit while the organs to be donated are evaluated and suitable candidates are determined through regional and national registries.

• If the potential donor has a do not resuscitate (DNR) order in place and the family has given consent to donate organs, the DNR is revoked with the knowledge and consent of the family. Thus, if a cardiac arrest occurs, advanced cardiac life support (ACLS) is initiated. If resuscitation attempts fail and recovery teams are available, the recovery process takes place as soon as possible.

• Costs incurred are the responsibility of the regional OPO.

• Early referral to the local OPO is of prime importance. Two common recognition points are a Glasgow Coma Scale score of 5 or less and the absence of two or more brain stem reflexes, which are indicative of a poor outcome in at least 70% of the patients.3

• “First mention” and “decoupling” are two important concepts related to early referral and early intervention.

• First mention involves the healthcare provider providing an awareness of the possibility of donation. Early awareness of the possibility of organ donation correlates with family consent to donate organs, whereas families surprised by the possibility of organ donation are more likely to react negatively.7 Thus, families may be more likely to donate if they are prepared that a request will be made.3

• Decoupling refers to the timing of the pronouncement of patient death (or the anticipation of death) and the request to consider donation of organs. The two events should not occur at the same time.

EQUIPMENT

• Central venous access (e.g., pulmonary artery or triple-lumen catheter)

• Blood pressure monitoring system (invasive or noninvasive)

Additional equipment, to have available as needed, includes the following:

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Inform the family of the patient’s current condition.  Rationale: The family is kept informed and is prepared for realistic expectations of the patient’s outcome.

Rationale: The family is kept informed and is prepared for realistic expectations of the patient’s outcome.

• After the OPO has formally requested family consent for organ donation, collaborate with the OPO in answering important family questions. Family members may want information regarding which organ(s) can be donated, possible disfigurement, hospital costs, funeral arrangements, etc.  Rationale: This provides family members with important information and may decrease family anxiety regarding the donation process.

Rationale: This provides family members with important information and may decrease family anxiety regarding the donation process.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

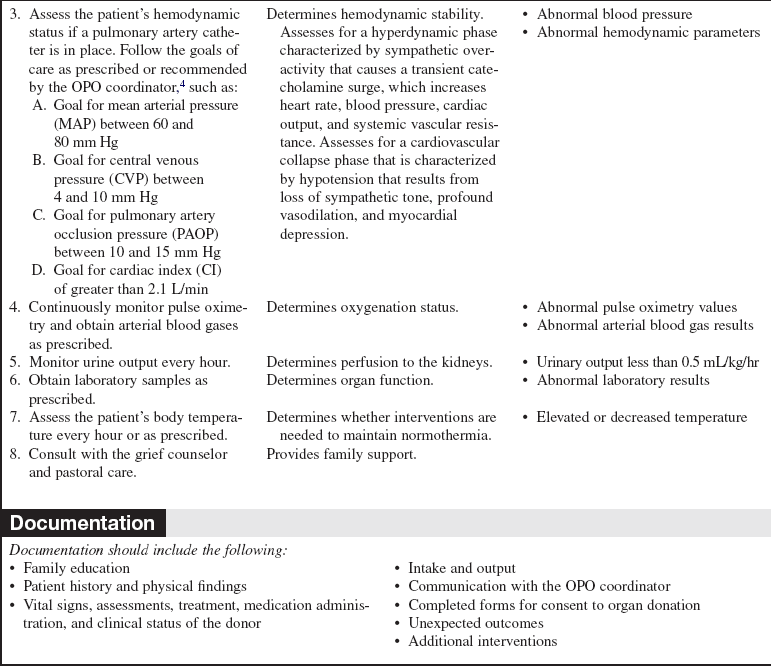

• Assess the patient’s vital signs, hemodynamic parameters, and fluid status.  Rationale: Assessment provides baseline data and important data regarding the organ survivability to transplant.

Rationale: Assessment provides baseline data and important data regarding the organ survivability to transplant.

• Assess the patient’s current laboratory results (e.g., electrolyte, blood urea nitrogen, creatinine).  Rationale: Assessment provides baseline data and important data regarding the organ survivability to transplant.

Rationale: Assessment provides baseline data and important data regarding the organ survivability to transplant.

• Assess oxygenation.  Rationale: Assessment provides baseline data and important data regarding the organ survivability to transplant.

Rationale: Assessment provides baseline data and important data regarding the organ survivability to transplant.

• Obtain a thorough medical and social history from the family about the patient, including age, injuries, chronic diseases, and family, social, medical, and surgical history. Of particular interest is any history of renal, cardiac, liver, pulmonary, or pancreatic disease; malignant disease; hepatitis; diabetes; or human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) status. In the case of young female patients, pregnancy status should be determined before donation. In the case of young male patients, families should be aware of the possibility for sperm donation.  Rationale: This information assists the OPO transplant coordinator in assessment of the medical suitability of the patient for organ donation and possible patient-specific considerations.

Rationale: This information assists the OPO transplant coordinator in assessment of the medical suitability of the patient for organ donation and possible patient-specific considerations.

• Assess the family members’ understandings of the patient’s current condition, prognosis, and plan of care.  Rationale: Assessment aids in determining family understanding. Organ donation should not be discussed until family members acknowledge their loved one’s terminal status.7

Rationale: Assessment aids in determining family understanding. Organ donation should not be discussed until family members acknowledge their loved one’s terminal status.7

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the family understands preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• When neurologic testing to determine clinical brain death begins, ensure that the patient is normothermic and that no sedating or paralyzing medications have been given.  Rationale: Hypothermia and sedating or paralyzing medications interfere with brain death testing.

Rationale: Hypothermia and sedating or paralyzing medications interfere with brain death testing.

• Facilitate the discussion of organ donation by notification of the OPO.  Rationale: The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require that all deaths be reported to the OPO regardless of age or circumstances. Many OPOs have instituted the use of clinical triggers to initiate the referral. The triggers are based on OPO and hospital agreed-upon physical examination findings.

Rationale: The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require that all deaths be reported to the OPO regardless of age or circumstances. Many OPOs have instituted the use of clinical triggers to initiate the referral. The triggers are based on OPO and hospital agreed-upon physical examination findings.

• Patients who are brain dead are potential candidates for organ donation. Follow hospital policy regarding first mention.  Rationale: Request for organ donation is the responsibility of representatives from the OPO or a specially trained designated hospital requester after consultation with the OPO.7

Rationale: Request for organ donation is the responsibility of representatives from the OPO or a specially trained designated hospital requester after consultation with the OPO.7

• If a decision is made to donate organs, follow the plan of care determined by the OPO.  Rationale: The plan of care provides important care to promote organ survivability to transplant.

Rationale: The plan of care provides important care to promote organ survivability to transplant.

• An arterial catheter may be inserted, if not already in place.  Rationale: Assessment of blood pressure and ease of blood sampling are facilitated.

Rationale: Assessment of blood pressure and ease of blood sampling are facilitated.

• Involve additional hospital resources (e.g., clergy, grief counselors, palliative care specialists).  Rationale: Additional family support is provided throughout the end-of-life process. Pastoral care may offer additional insights into faith, hope, and encouragement to those who may be experiencing despondency, remorse, guilt, or anger at this time.

Rationale: Additional family support is provided throughout the end-of-life process. Pastoral care may offer additional insights into faith, hope, and encouragement to those who may be experiencing despondency, remorse, guilt, or anger at this time.

References

![]() 1. Brook, NR, Nicholson, ML, Kidney transplant from non heart-beating donors. Surg J Royal Coll Surg Edinb Ireland . 2003; 1:311–322.

1. Brook, NR, Nicholson, ML, Kidney transplant from non heart-beating donors. Surg J Royal Coll Surg Edinb Ireland . 2003; 1:311–322.

![]() 2. Doig, CJ, Rocker, G, Retrieving organs from non-heart-beating organ donors. a review of medical and ethical issues. Can J Anesth 2003; 50:1069–1076.

2. Doig, CJ, Rocker, G, Retrieving organs from non-heart-beating organ donors. a review of medical and ethical issues. Can J Anesth 2003; 50:1069–1076.

3. Ehrle, R. Timely referral of potential organ donors. Crit Care Nurse. 2006; 26:88–93.

![]() 4. Intensive Care Society. Guidelines for adult organ and tissue donation. www.ics.ac.uk, 2004. [retrieved November 3, 2008, from].

4. Intensive Care Society. Guidelines for adult organ and tissue donation. www.ics.ac.uk, 2004. [retrieved November 3, 2008, from].

5. Joint Commission, JCAHO standards related to organ donation. www.jointcommission.org, 2008 [retrieved November 3, 2008, from].

6. Joint, Commission. Revisions to standard LD. 3. 110. Joint Commission Perspect. 2006; 26:7.

![]() 7. Metzger, RA, et al, Research to practice. a national consent conference. Prog Transplant 2005; 15:1–6.

7. Metzger, RA, et al, Research to practice. a national consent conference. Prog Transplant 2005; 15:1–6.

8. New York Organ Donor Network. History of organ transplantation. www.donatelifeny.org, 2008. [retrieved October 21, 2008, from].

9. OrganDonor, Gov. Access to U. S. government information on organ & tissue donation and transplantation. www.organdonor.gov, 2010. [retrieved May 4, 2010 from].

![]() 10. Siminoff, LA, et al, Factors influencing families’ consent for donation of solid organs for transplantation . JAMA 2001; 286:71–77.

10. Siminoff, LA, et al, Factors influencing families’ consent for donation of solid organs for transplantation . JAMA 2001; 286:71–77.