Determination of Death in Adult Patients

Determination of Death in Adult Patients

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Death is determined with either irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions or irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brain stem.

• Historically, death had been described as the cessation of circulation and respiration (cardiopulmonary death). The advent of mechanical ventilation and cardiovascular support, however, presented new challenges for determination of death in patients with catastrophic cerebral insults whose cardiopulmonary function could be preserved with complex technology.3,5

• Initial efforts to define death in an age of technologic advancement included the development of the Harvard criteria, which described determination of a condition known as irreversible coma, cerebral death, or brain death.1

• Since the initial introduction of the Harvard criteria, the Uniform Determination of Death Act (UDDA) was published in 1980 and was recommended by the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Biobehavioral Research as a model statute for state legislation defining death.3

• UDDA asserts that “an individual who has sustained either (1) irreversible cessation of circulatory and respiratory functions, or (2) irreversible cessation of all functions of the entire brain, including the brainstem, is dead. A determination of death must be made in accordance with accepted medical standards.”3

• In cases of either cardiopulmonary or brain death, diagnosis of death requires both cessation of function and irreversibility.

• In cardiopulmonary death, cessation of function is determined with clinical examination.

• In cardiopulmonary death, irreversibility is confirmed with persistent cessation of functions during a period of observation.

• In brain death, cessation of function is determined when clinical evaluation discloses absence of both cerebral and brain stem function.

• In brain death, irreversibility is determined when the etiology of the coma is sufficient to account for the loss of brain function is established, the possibility of recovery of brain function is excluded, and the cessation of all brain function persists for a period of observation or therapy.3,5

• The concept of brain death continues to be a topic of international debate among clinicians, anthropologists, philosophers, and ethicists. This ongoing dialogue concerning the determination of death is a process of developing multidisciplinary consensus that is responsive to continually changing technology.6,7

• Although conceptualization of death continues to evolve, experts have generated clinical practice parameters for brain death diagnosis that are grounded in empirical knowledge, supported by sufficiently rigorous research, and substantiated by high degrees of clinical certainty.6,7

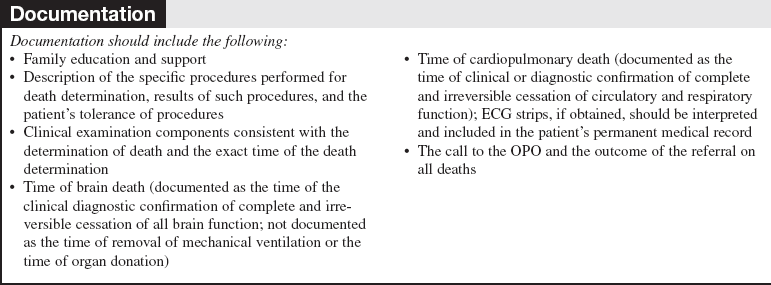

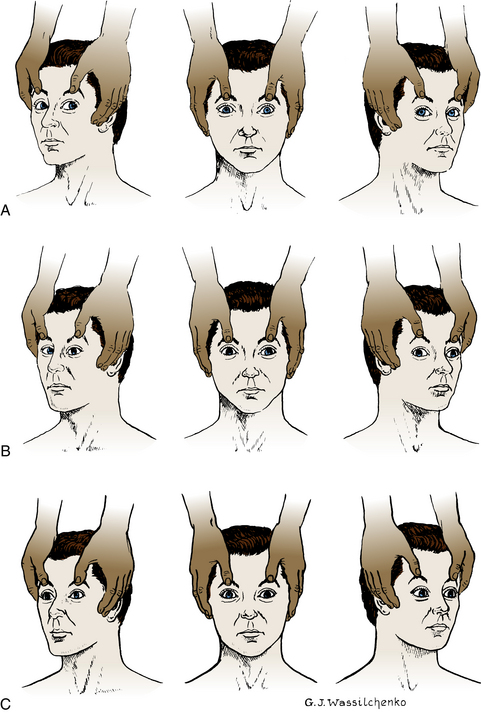

• Cardinal findings in brain death include coma or unresponsiveness, apnea, absence of cerebral motor responses to pain in all extremities, and absence of brain stem reflexes, including pupillary signs, ocular movements, facial sensory and motor responses, and pharyngeal and tracheal reflexes.

• Legal responsibility for assessment and declaration of death varies by state. Some states permit registered nurses and advanced practice nurses to determine death.

EQUIPMENT

• For cardiopulmonary death determination:

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

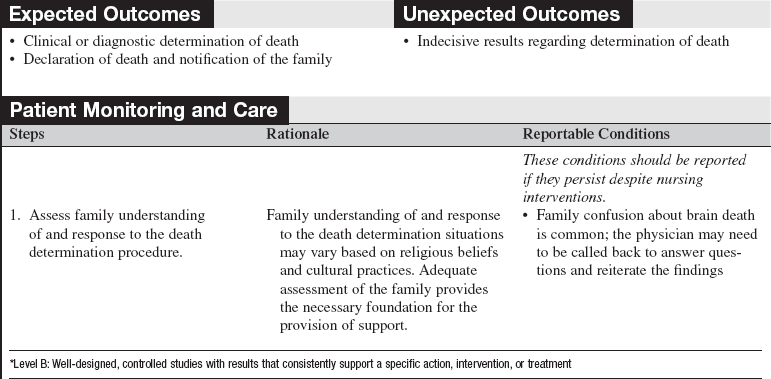

• Assess family understanding of the death determination procedure and its purpose.  Rationale: Clarification and repeat explanation may assist in allaying some stress and anxiety for grief-stricken family members.

Rationale: Clarification and repeat explanation may assist in allaying some stress and anxiety for grief-stricken family members.

• Explain potential outcomes of the death determination procedure.  Rationale: Awareness of the duration and expectations of death determination procedures may allay some stress and anxiety in grief-stricken family members.

Rationale: Awareness of the duration and expectations of death determination procedures may allay some stress and anxiety in grief-stricken family members.

• Assess family understanding of the concept of “brain-dead” if testing for brain death. Give clear definition of brain death and death as synonymous and reinforce repeatedly with the family.  Rationale: The concept of brain death may be confusing to family members because the term “brain dead” may imply that only the brain is dead and the rest of the body is alive. Brain death must be described as death.

Rationale: The concept of brain death may be confusing to family members because the term “brain dead” may imply that only the brain is dead and the rest of the body is alive. Brain death must be described as death.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess the patient’s baseline cardiopulmonary and neurologic status in preparation for determination of death.  Rationale: In cardiopulmonary death, clinical examination discloses absence of responsiveness, heartbeat, and respiratory effort. In brain death, clinical examination reveals an absence of both cerebral and brain stem function.

Rationale: In cardiopulmonary death, clinical examination discloses absence of responsiveness, heartbeat, and respiratory effort. In brain death, clinical examination reveals an absence of both cerebral and brain stem function.

• For brain death determination, the following prerequisites must also be met:

Acquire evidence of an acute catastrophic cerebral event consistent with the clinical diagnosis of brain death.

Acquire evidence of an acute catastrophic cerebral event consistent with the clinical diagnosis of brain death.

Exclude conditions that may confound the clinical assessment of brain death, such as acute metabolic or endocrine derangements or neuromuscular blockade.

Exclude conditions that may confound the clinical assessment of brain death, such as acute metabolic or endocrine derangements or neuromuscular blockade.

Confirm the absence of drug intoxication or poisoning.

Confirm the absence of drug intoxication or poisoning.

Maintain the patient’s core body temperature greater than or equal to 32°C.

Maintain the patient’s core body temperature greater than or equal to 32°C.

Rationale: The brain death determination procedure must confirm both cessation and irreversibility of all brain function. The previous four criteria are required for the confirmation of irreversible cessation of brain function.

Rationale: The brain death determination procedure must confirm both cessation and irreversibility of all brain function. The previous four criteria are required for the confirmation of irreversible cessation of brain function.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the family understands preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Facilitate the discussion of organ donation by notifying the organ procurement organization (OPO).  Rationale: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require that all deaths be reported to the local OPO regardless of age or circumstances. Many OPOs have instituted the use of clinical triggers to initiate the referral. The triggers are based on OPO and hospital agreed-on physical examination findings. Patients who are brain dead are potential candidates for organ donation. Request for organ donation is the responsibility of representatives from the OPO or a specially trained designated hospital requester after consultation with the OPO (see Procedure 136).2

Rationale: Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) require that all deaths be reported to the local OPO regardless of age or circumstances. Many OPOs have instituted the use of clinical triggers to initiate the referral. The triggers are based on OPO and hospital agreed-on physical examination findings. Patients who are brain dead are potential candidates for organ donation. Request for organ donation is the responsibility of representatives from the OPO or a specially trained designated hospital requester after consultation with the OPO (see Procedure 136).2

• Place the patient in a supine position.  Rationale: Positioning facilitates patient assessment, oculovestibular testing, and arterial puncture.

Rationale: Positioning facilitates patient assessment, oculovestibular testing, and arterial puncture.

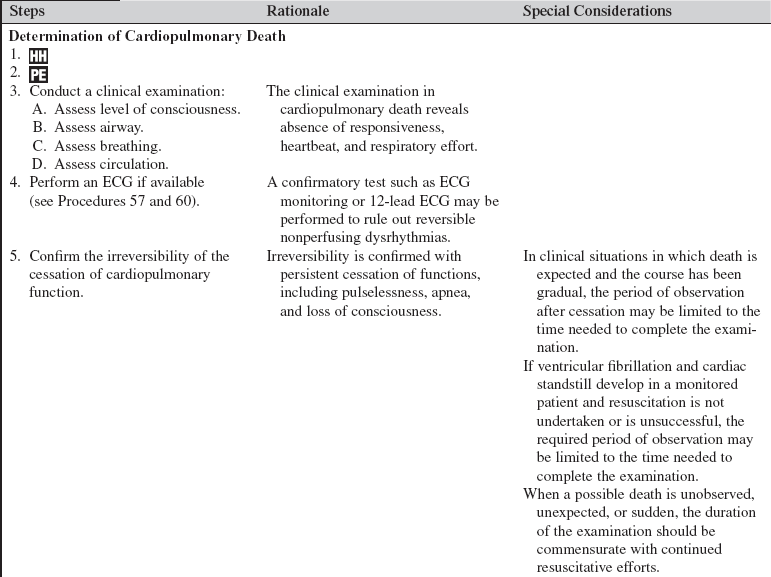

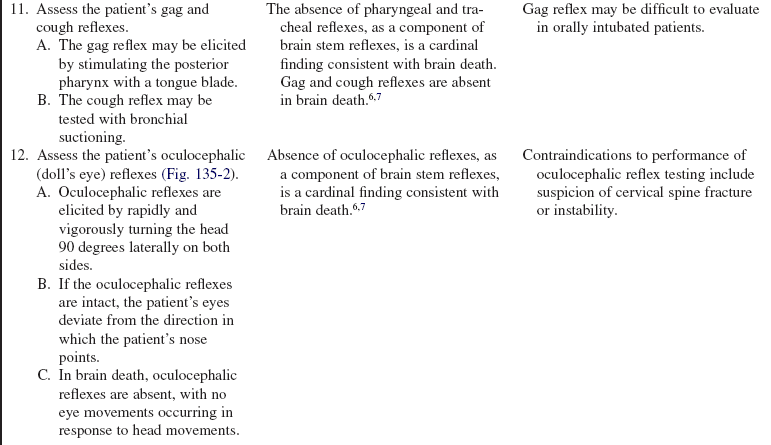

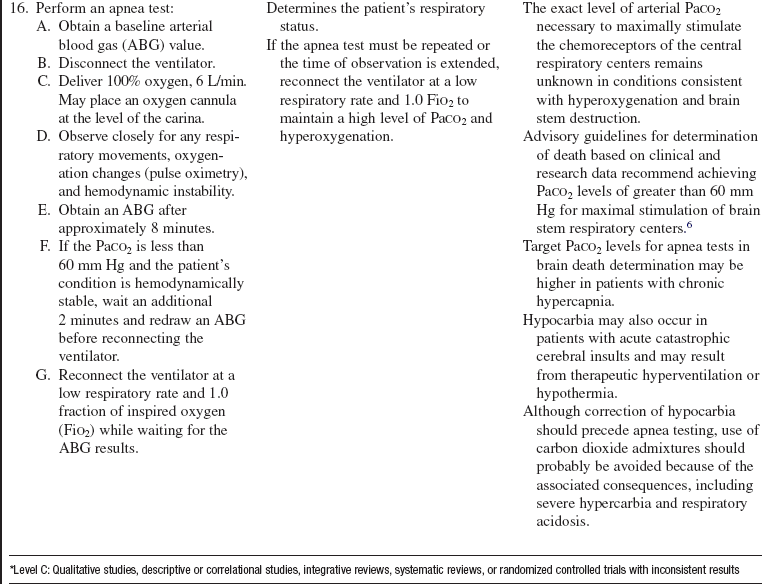

Table 135-1

| Positive apnea test results | Respiratory movements are absent. Posttest arterial PaCO2 is ≥ 60 mm Hg. Supports clinical determination of brain death. |

| Negative apnea test results | Respiratory movements are observed regardless of arterial PaCO2 level. Does not support clinical determination of brain death; apnea test may be repeated after a change in clinical status is observed. |

| Apnea test results of cardiovascular or pulmonary instability | Systolic blood pressure falls below 90 mm Hg. Arterial oxygen desaturation below therapeutic levels occurs. Cardiac dysrhythmias occur. Immediately draw an arterial blood gas sample and reconnect the ventilator. Confirmatory test to finalize clinical determination of brain death may be performed. |

| Inconclusive apnea test results | No respiratory movements are observed. Posttest arterial PaCO2 is < 60 mm Hg without significant cardiovascular instability. Apnea test may be repeated with 10 minutes of apnea. |

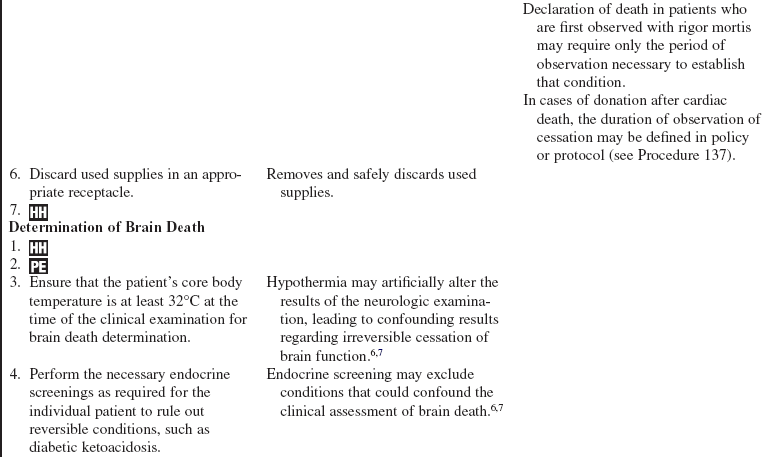

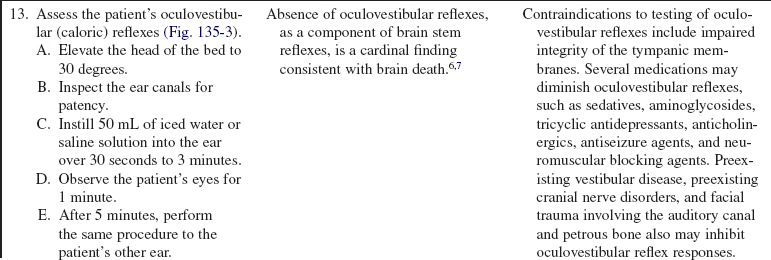

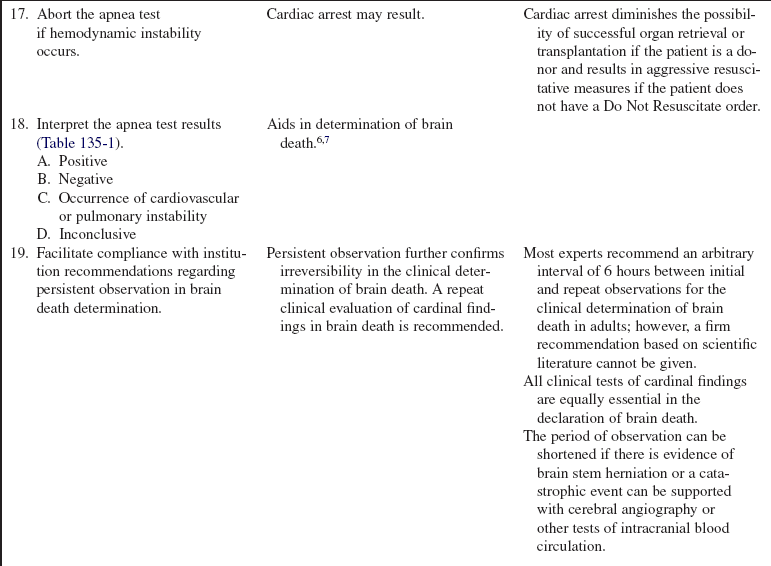

Table 135-2

Confirmatory Brain Death Test Results

| Cerebral angiography | No intracerebral filling at the level of the carotid bifurcation or circle of Willis External carotid circulation patent |

| Electroencephalogram (EEG) | No electrical activity during a period of at least 30 minutes of recording |

| Transcranial Doppler ultrasound scan | Absent diastolic or reverberating flow Flow only through systole or retrograde diastolic flow Small systolic peaks in early systole |

| Technetium 99m brain scan (cerebral blood flow scan) | No uptake of isotope in brain parenchyma (“hollow skull phenomenon”) |

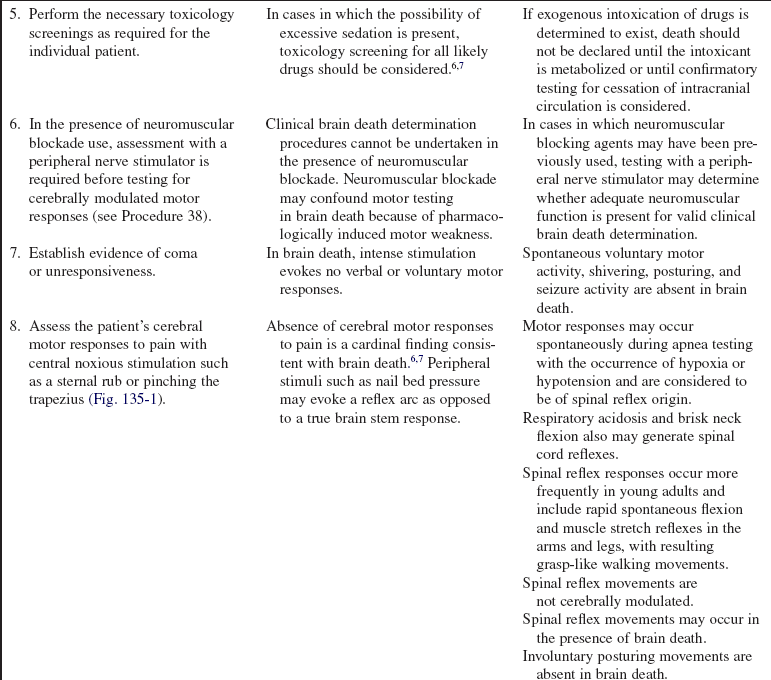

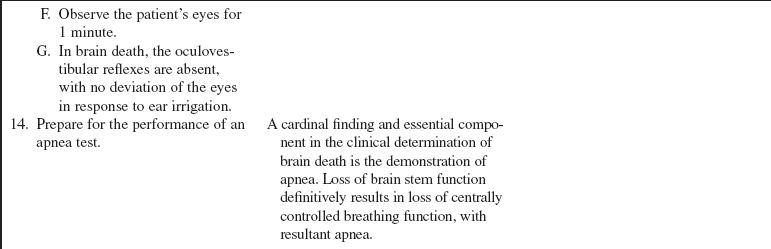

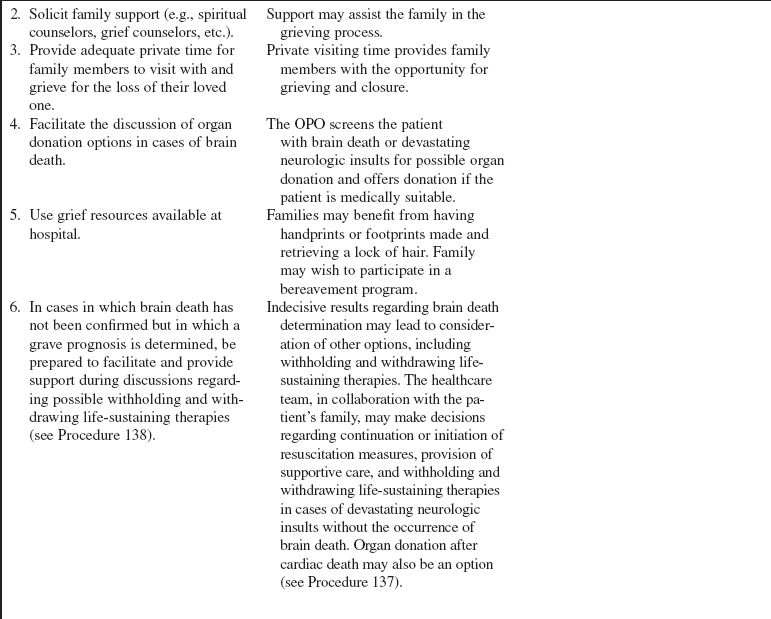

Figure 135-1 The trapezius pinch.

References

![]() 1. A definition of irreversible coma. report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death. JAMA. 1968; 205(6):337–340.

1. A definition of irreversible coma. report of the Ad Hoc Committee of the Harvard Medical School to Examine the Definition of Brain Death. JAMA. 1968; 205(6):337–340.

2. Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Hospital conditions of participation about organ/tissue donation,. www.cms.gov/manuals/downloads/som107ap_a_hospitals.pdf, November 6, 2008. [retrieved].

![]() 3. Guidelines for the determination of death, report of the medical consultants on the diagnosis of death to the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research . JAMA. 1981; 246(19):2184–2186.

3. Guidelines for the determination of death, report of the medical consultants on the diagnosis of death to the President’s Commission for the Study of Ethical Problems in Medicine and Biomedical and Behavioral Research . JAMA. 1981; 246(19):2184–2186.

4. Heran, MK, Heran, NS, Shemie, SD. A review of ancillary tests in evaluating brain death. Can J Neurol Sci. 2008; 35(4):409–419.

![]() 5. Practice parameters for determining brain death in adults (summary statement), the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology . Neurology. 1995; 45(5):1012–1014.

5. Practice parameters for determining brain death in adults (summary statement), the Quality Standards Subcommittee of the American Academy of Neurology . Neurology. 1995; 45(5):1012–1014.

![]() 6. Wijdicks, EF, Determining brain death in adults . Neurology. 1995; 45(5):1003–1011.

6. Wijdicks, EF, Determining brain death in adults . Neurology. 1995; 45(5):1003–1011.

7. Wijdicks, EF, Rabinstein, AA, Manno, EM, et al, Pronouncing brain death. contemporary practice and safety of the apnea test . Neurology. 2008; 71(16):1240–1244.

8. Young, GB, Shemie, SD, Doig, CJ, et al, Brief review. the role of ancillary tests in the neurological determination of death. Can J Anaesth. 2006; 53(6):620–627.