Negative-Pressure Wound Therapy

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is an advanced wound care therapy that uses an occlusive wound dressing, tubing, and powered vacuum unit with a collection canister. Other terms found in the literature for NPWT include topical negative therapy (TPN) and subatmospheric pressure therapy.

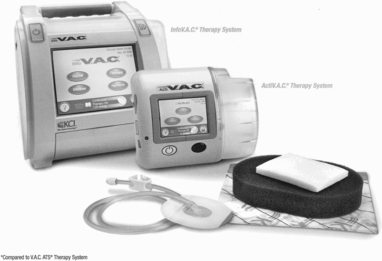

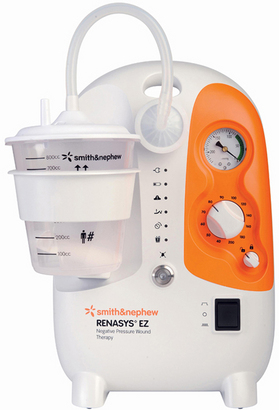

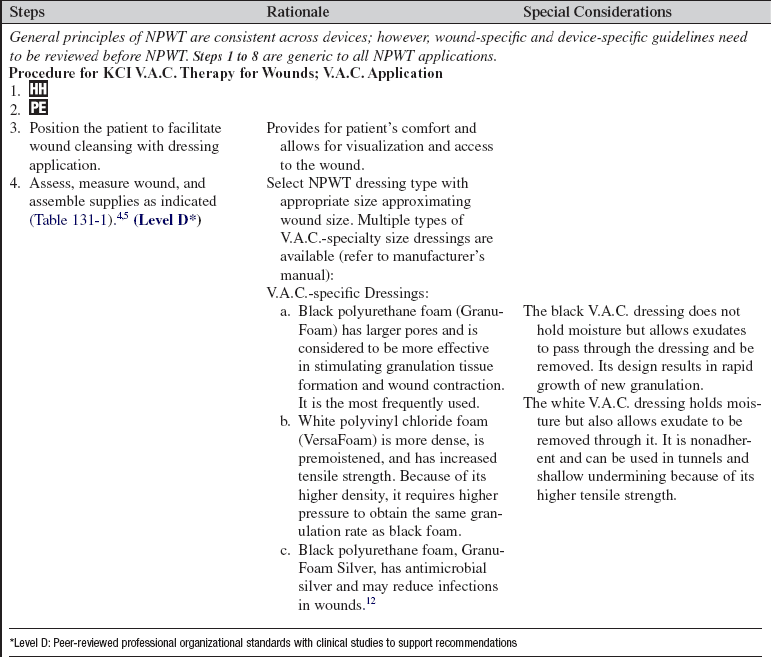

• Many different U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved vacuum units are on the market for NPWT.10 The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ) provides a review of current NPWT manufacturers.11 The most common devices seen in the acute care practice setting are ActiV.A.C.® and InfoV.A.C. Therapy Systems (KCI Licensing, Inc., San Antonio, TX; Fig. 131-1) and RENASYS EZ® (Smith & Nephew, St. Petersburg, FL8; Fig. 131-2). ActiV.A.C.® and Info V.A.C.®12 use a patented open-cell foam wound contact dressing, and RENASYS EZ®6 (and other newly developing units on the market) uses either an open-cell foam or the vacuum-pack method with an antimicrobial gauze packing dressing. The use of moistened gauze wound interface has also been reported in the literature as an effective dressing for NPWT.7

• Most randomized controlled studies and case studies on NPWT have been conducted with the V.A.C. therapy. No randomized controlled trials are found that compare the effectiveness of various NPWT techniques or systems.11 Further clinical research to evaluate wound closure outcomes with the different NPWT units is needed.5,8,10,11

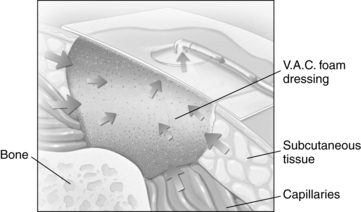

• NPWT assists with wound closure by applying a controlled subatmospheric (negative) pressure evenly over a wound bed. This mechanical stress creates a noncompressive force on the wound bed that dilates the arterioles, increasing the effectiveness of local circulation and enhancing the proliferation of granulation tissue.1,4,5 NPWT enhances lymphatic flow and removal of excessive fluid, decreasing wound edema and bacterial load at the wound site, further aiding wound healing (Fig. 131-3).1,2,4,5,9,10

• Wound healing is best achieved through adequate cleansing, débridement, and dressing of the wound bed on the basis of patient and wound characteristics.

• Wounds heal by either primary or secondary intention (see Fig. 126-1). Most clean surgical wounds heal by primary intention. Suturing each layer of tissue approximates the wound edges. These wounds typically heal quickly and require minimal wound care. Contaminated surgical or traumatic wounds (open wounds) heal by secondary intention. Wounds that heal by secondary intention granulate from the base of the wound to the skin surfaces; care must be taken to allow for uniform granulation and prevention of open pockets or tunneling.

• Openly granulating wounds heal more slowly and must remain moist to enhance tissue granulation. Wound care for these wounds focuses on maintaining a moist environment free of necrotic tissue, and decreasing pain.

• Open wounds may have excessive wound drainage that necessitates application of absorptive dressings, protection of periwound skin, and more frequent dressing changes to facilitate healing. NPWT provides wound drainage management and decreased frequency of dressing changes (most NPWT dressing changes are three times per week) with improved pain management.

• NPWT has been approved by the U.S. FDA for the following wounds:

Acute wounds (orthopedic trauma wounds, partial-thickness burns, abdominal wounds, surgical dehisced wounds, flaps, and grafts)

Acute wounds (orthopedic trauma wounds, partial-thickness burns, abdominal wounds, surgical dehisced wounds, flaps, and grafts)

Chronic wounds (diabetic wounds, pressure ulcers, leg ulcers)

Chronic wounds (diabetic wounds, pressure ulcers, leg ulcers)

• Goals of NPWT in the management of wounds may include wound bed preparation for skin grafts, full wound closure, decrease in wound size, removal of wound edema for delayed primary closure, and increased perfusion to marginally viable flaps.

• The effectiveness of NPWT should be evaluated with each dressing change to include a comprehensive wound assessment and weekly wound measurements. If wound measurements have not improved at least 15% after 2 weeks of therapy, reevaluate the continuation of NPWT with reassessment of wound healing variables.13

• Wounds with infections should have systemic antibiotic treatment before initiation of NPWT. If continued deterioration of the wound or infection persists, consider discontinuation of NPWT with possible evaluation for surgical drainage of infection per healthcare provider.

• Wounds treated with NPWT develop a characteristic, beefy red granulation bed. Pale, friable granulation tissue is a secondary sign of infection and may be more reliable than the traditional indicators of infection.3

• Dehisced infected sternal wounds with use of NPWT require effective débridement of infected bone and a specific nonadherent wound contact layer before a NPWT dressing is placed.

• Successful management of enteric fistulae with NPWT with use of special application techniques has been reported in case studies but no clinical trials at this time. See NPWT device manuals for specific techniques in the management of fistulae.

• Rapid formation of granulation tissue with NPWT can lead to development of abscesses. The surgically dehisced wound with NPWT should be monitored closely for abscess formation, particularly in patients with large irregular wounds with undermining present.

• Transcutaneous oxygen pressure (TcpO2) evaluation should be considered before initiation of NPWT to lower extremity or toe wounds because of vascular flow requirements that are needed for optimal wound healing with NPWT.

• Contraindications to use of NPWT include malignancy disease in the wound, untreated osteomyelitis, nonenteric and unexplored fistulae, and necrotic tissue with eschar present.10 See manufacturer NPWT manual for special precautions required with exposed blood vessels, organs, tendons, and nerves. Precautions should be used for wounds with active bleeding, for difficult wound hemostasis, and for patients undergoing anticoagulation therapy.

• For optimal NPWT with the V.A.C. device, at least 22 of 24 hours of daily uninterrupted therapy should be delivered. The newer vacuum units do not have research evidence at this time for required time duration of uninterrupted therapy for optimal wound healing. NPWT dressings are usually changed every 48 hours.5,7–10 However, infected wound beds may require more frequent dressing changes (every 12 hours), and dressings over grafts may be changed less frequently (every 3 to 5 days).5,8 The wound bed should be free of necrotic tissue and debris before application of the NPWT dressing.

• In highly exudative wounds, drainage from the wound bed may be significant in the first 24 to 48 hours of therapy. Studies have not suggested direct fluid replacements as necessary for ensuring homeostasis in highly exudative wounds.1,3,4 Excessive bleeding should be noted for discontinuation of therapy.

• Nutritional requirements for wound healing are great. These needs must be assessed, met, and monitored frequently because poor nutrition can impede successful NPWT wound healing.

• The NPWT units discussed previously (ActiV.A.C.® and InfoV.A.C.® Therapy Systems and RENASYS EZ®) have home units with increased portability. Smaller size and increased battery life allow for continuation of therapy outside of the acute hospital setting.

EQUIPMENT

• Standard Precautions equipment: gloves, gown, as indicated per institution policy

• Normal Precautions or wound cleanser with appropriate psi delivery device (see Procedure 126)

• Protective barrier film/wipe for periwound protection

• NPWT dressing with tubing/transparent drape kit (device-specific)

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Assess patient and family readiness to learn and any factors that may affect learning. Identification of the patient’s preferred learning strategies (auditory, visualization, return demonstration) is also important.  Rationale: The nurse can develop the most appropriate teaching strategy for each patient.

Rationale: The nurse can develop the most appropriate teaching strategy for each patient.

• Provide information about NPWT, the procedure, and the equipment.  Rationale: Information may decrease or alleviate anxiety by assisting patient and family to understand the procedure, why it is needed, and the preferred outcomes.

Rationale: Information may decrease or alleviate anxiety by assisting patient and family to understand the procedure, why it is needed, and the preferred outcomes.

• Explain the procedure and the reason for changing wound dressing.  Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased.

Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased.

• Discuss patient’s role during the dressing change procedure and in maintaining the NPWT system.  Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited; patient is prepared for wound management on discharge.

Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited; patient is prepared for wound management on discharge.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Fully assess wound with documentation of wound measurements, characteristics, and appropriateness for the procedure.  Rationale: Assessment ensures that use of NPWT is not contraindicated. Data are provided for comparison at successive dressing changes.

Rationale: Assessment ensures that use of NPWT is not contraindicated. Data are provided for comparison at successive dressing changes.

• Assess for signs and symptoms of wound infection, including the following:

Rationale: Although NPWT assists with removal of excessive fluid, thus reducing the potential of bacteria in the wound bed, assessment for signs and symptoms of wound infection is necessary, especially in patients with compromised conditions.

Rationale: Although NPWT assists with removal of excessive fluid, thus reducing the potential of bacteria in the wound bed, assessment for signs and symptoms of wound infection is necessary, especially in patients with compromised conditions.

• Determine baseline pain assessment.  Rationale: Data are provided for comparison with past procedure assessment data. The nurse can plan for preprocedure and intraprocedure analgesia.

Rationale: Data are provided for comparison with past procedure assessment data. The nurse can plan for preprocedure and intraprocedure analgesia.

• Determine baseline nutritional and fluid volume status.  Rationale: Adequate fluids and protein are necessary for optimal wound healing with NPWT.

Rationale: Adequate fluids and protein are necessary for optimal wound healing with NPWT.

• Assess medical history, especially related to bleeding problems, fistula formation, or malignant disease.  Rationale: NPWT may be contraindicated in these conditions.

Rationale: NPWT may be contraindicated in these conditions.

• Assess current medications specifically related to anticoagulant use.  Rationale: Possible areas of caution that should be monitored with NPWT use are identified.

Rationale: Possible areas of caution that should be monitored with NPWT use are identified.

• Assess current laboratory values, especially coagulation studies.  Rationale: Abnormalities possibly associated with risks related to NPWT use are identified.

Rationale: Abnormalities possibly associated with risks related to NPWT use are identified.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure patient and family understanding of procedure. Reinforce teaching points as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated, and a conduit for questions is provided.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated, and a conduit for questions is provided.

• Validate presence of patent intravenous access.  Rationale: Access may be needed for administration of intravenous analgesic medications.

Rationale: Access may be needed for administration of intravenous analgesic medications.

• Position the patient in a manner that will ensure patient comfort and privacy and facilitate dressing application.  Rationale: Patient is prepared to undergo procedure.

Rationale: Patient is prepared to undergo procedure.

• Administer prescribed analgesics if needed.  Rationale: Analgesics improve comfort level and tolerance of the procedure and decrease patient anxiety and discomfort.

Rationale: Analgesics improve comfort level and tolerance of the procedure and decrease patient anxiety and discomfort.

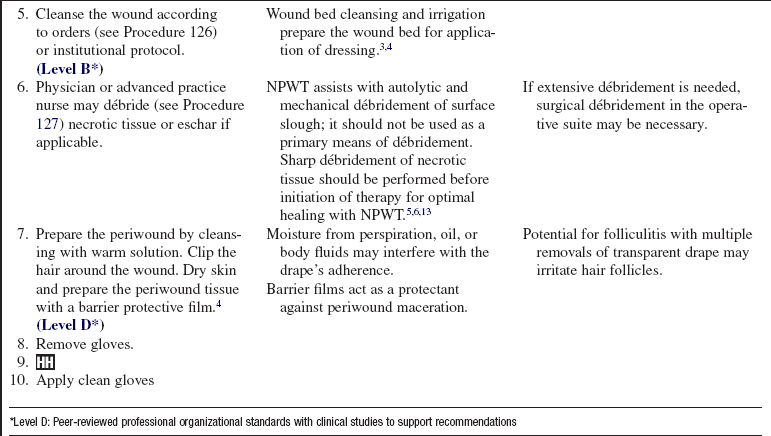

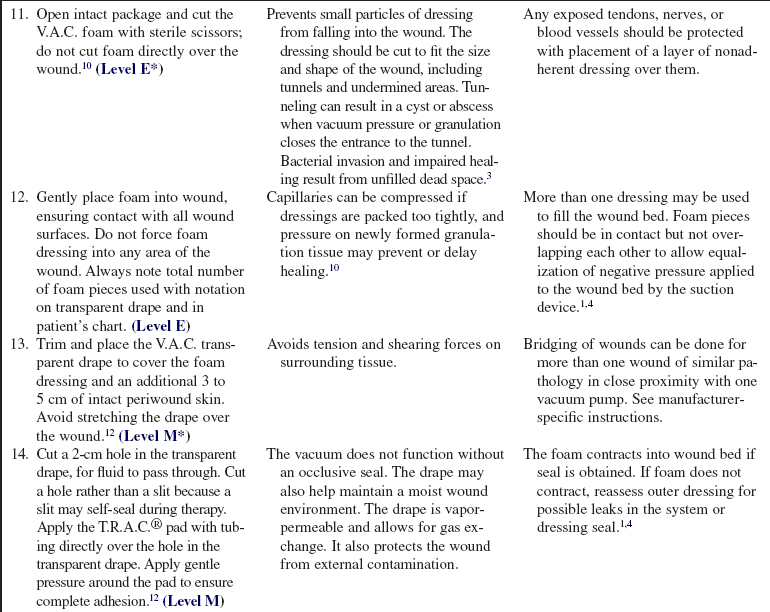

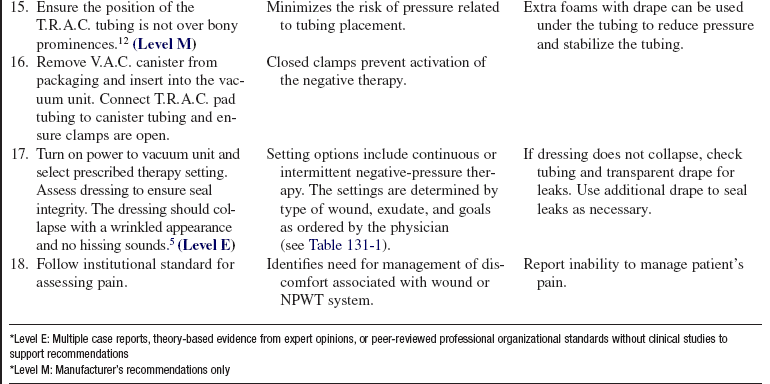

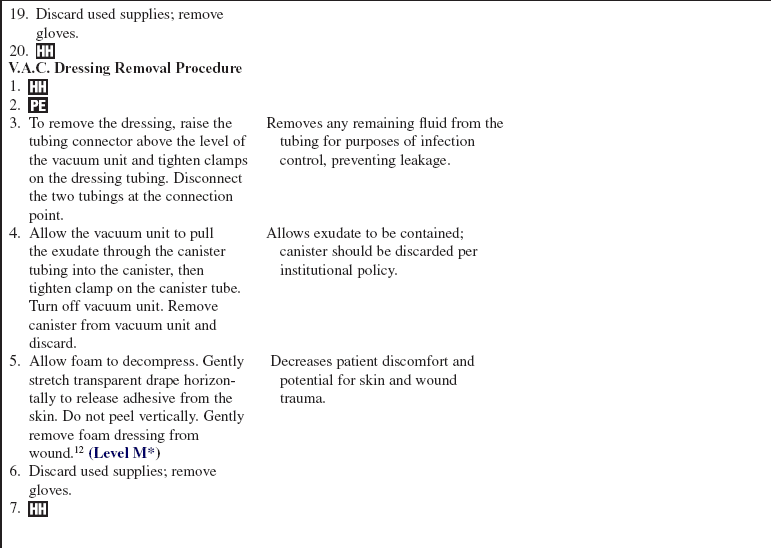

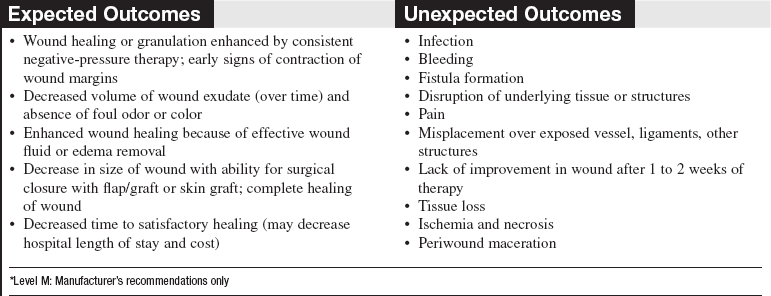

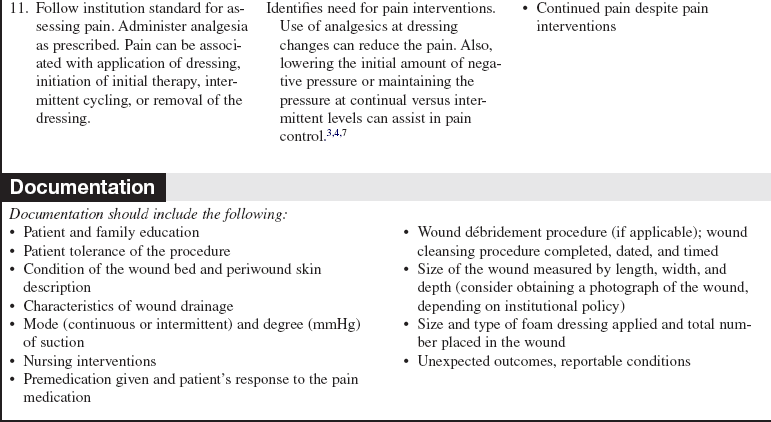

Table 131-1

Recommended Therapy Setting for KCI V.A.C. Therapy

| Wound Characteristics | Continuous Therapy | Intermittent Therapy |

| Difficult dressing application | x | |

| Flap | x | |

| Highly exuding | x | |

| Grafts | x | |

| Painful wounds | x | |

| Tunnels or undermining | x | |

| Unstable structures | x | |

| Minimally exuding | x | x |

| Large wounds | x | x |

| Small wounds | x | x |

| Stalled wound healing progress | x | x |

| V.A.C. white foam dressing | x | x |

(Adapted from Smith APS: V.A.C.® therapy clinical guidelines: a reference source for clinicians, San Antonio, TX, 2006, KCI Licensing, Inc.)

References

![]() 1. Argenta, LC, Morykwas, MJ, Vacuum-assisted closure. a new method for wound control and treatmentclinical experience. Ann Plastic Surg 1997; 38:563–576.

1. Argenta, LC, Morykwas, MJ, Vacuum-assisted closure. a new method for wound control and treatmentclinical experience. Ann Plastic Surg 1997; 38:563–576.

![]() 2. Armstrong, D, et al. Proceedings from the 2003 National V. A. C. ® Education Conference. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004; 50(4A Suppl):3S–27S.

2. Armstrong, D, et al. Proceedings from the 2003 National V. A. C. ® Education Conference. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2004; 50(4A Suppl):3S–27S.

![]() 3. Bergstrom, N, et al, Treatment of pressure ulcers. clinical practice guideline, no. 15. US Department of Health and -Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for -Healthcare Policy and Research, Rockville, MD, 1994. [AHCPR publication no. 95-0652].

3. Bergstrom, N, et al, Treatment of pressure ulcers. clinical practice guideline, no. 15. US Department of Health and -Human Services, Public Health Service, Agency for -Healthcare Policy and Research, Rockville, MD, 1994. [AHCPR publication no. 95-0652].

4. Broughton, G, et al, Wound healing. an overview. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 2006; 117(7S Suppl):1e-s–32e-s.

5. Bovill, E, et al, Topical negative pressure wound therapy. a review of its role and guidelines for its use in the management of acute wounds. Int Wound J. 2008; 65(3):722–731.

6. Campbell P, Smith J, Smith G, eds. Negative pressure wound therapy (NPWT) clinical case reports. St Petersburg, FL: Smith & Nephew, 2007.

7. Chariker, ME, Gerstle, TL, Morrison, CS. An algorithmic approach to the use of gauze-based negative-pressure wound therapy as a bridge to closure in pediatric extremity trauma. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 2009; 123(5):1510–1520.

8. Gupta, S, Differentiating negative pressure wound therapy devices. an illustrative case series. Wounds J. 2007; 19(1 Suppl):26S–28S.

9. Koehler, C, et al, Wound therapy using the vacuum-assisted closure device. clinical experience with novel indications. J Trauma. 2008; 65(3):722–732.

10. Long, MA, Blevins, A, Options in negative pressure wound therapy. five case studies. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009; 36(2):202–211.

11. Sullivan, N, Snyder, DL, Tipton, K, et al, Negative pressure wound therapy devices. technology assessment report, project ID WNDT1108. US Department of Health and Human Services, Agency for Healthcare Research Quality, Rockville, MD, 2009.. www.ahrq.gov/clinic/ta/negpresswtd [available at].

12. Smith, APS, V. A. C. ® therapy clinical guidelines. a reference source for clinicians. KCI Licensing, Inc, San Antonio, TX, 2006.

13. World Union of Wound Healing Societies (WUWHS). Principles of best practice: vacuum assisted closure. recommendation for use: a consensus document. MEP Ltd, London, 2008.