Fecal Containment Devices and Bowel Management System

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Critically ill patients have multiple risk factors that increase the chance of pressure ulcer development. A valid and reliable pressure ulcer risk assessment tool should be used to assess a patient’s risk on admission and consistently throughout the hospitalization.1

• Patients with fecal incontinence and immobility are considered to be at increased risk of pressure ulcers.13,17,20

• Acutely ill patients are at high risk of fecal incontinence related to administration of a variety of mediations (i.e., antimicrobial, cardiovascular, central nervous system [CNS], and gastrointestinal agents),19 enteral feeding,2,22 disease processes (e.g., gastrointestinal, hepatic disease, spinal cord trauma, etc.), and enterotoxins (e.g., Clostridium difficile).2

• Personal protective equipment should be used when the source of the diarrhea is not identified, to avoid the possible spread of highly infectious organisms.

• Urinary and fecal incontinence results in skin breakdown.5,6,8,22 Excessive moisture changes the skin’s protective pH and increases the permeability of the skin, decreasing its protective function. Fecal content is more irritating than urine because digestive enzymes in feces contribute to erosion of skin.13

• Perineal skin damage may progress rapidly and ranges in severity, presenting with erythema, edema, weeping, denuded skin, and pain.8,9,13,16,23 Other negative outcomes may include skin ulceration and secondary infection, including bacterial (Staphylococcus) and yeast (Candida albicans) infections that increase discomfort and treatment costs.8,13,15,16

• Incontinence-associated dermatitis (IAD) is inflammation of the skin that occurs when urine or stool comes into contact with perineal or perigenital skin.9 IAD is the clinical term used to describe incontinence-associated skin damage. IAD often occurs in conjunction with pressure and shear and friction forces that precipitate pressure ulcers.9

• It is well established that excessive moisture and incontinence, especially fecal incontinence, significantly increases the patient’s risk of IAD and pressure ulcers; the research to guide fecal containment practice is limited.1–3,6,9,14,17,22

• Management of fecal incontinence should include the following elements:

Identification and treatment of the diarrhea. If the source of fecal incontinence cannot be eliminated, drug therapy may be used; however, the efficacy of these drugs is not known because randomized studies have focused on the management of chronic diarrhea in outpatients rather than acute diarrhea in hospitalized patients.22

Identification and treatment of the diarrhea. If the source of fecal incontinence cannot be eliminated, drug therapy may be used; however, the efficacy of these drugs is not known because randomized studies have focused on the management of chronic diarrhea in outpatients rather than acute diarrhea in hospitalized patients.22

Meticulous perineal skin care. Maintain clean, healthy skin by cleansing the skin with a pH-balanced no-rinse skin cleansing solution after each episode of diarrhea. Avoid soap and water. Most soaps are alkaline, and the skin’s pH is acidic (5.0 to 6.5); use of soap and water to cleanse the skin can further disrupt the skin’s protective properties.7

Meticulous perineal skin care. Maintain clean, healthy skin by cleansing the skin with a pH-balanced no-rinse skin cleansing solution after each episode of diarrhea. Avoid soap and water. Most soaps are alkaline, and the skin’s pH is acidic (5.0 to 6.5); use of soap and water to cleanse the skin can further disrupt the skin’s protective properties.7

Apply a moisturizer with skin protectant. Moisturizers help hydrate intact skin, replace oils in the skin, and soothe skin irritation. Moisturizers that contain petrolatum, lanolin, dimethicone, or zinc can provide a protective barrier to protect and sooth denuded area.8,10

Apply a moisturizer with skin protectant. Moisturizers help hydrate intact skin, replace oils in the skin, and soothe skin irritation. Moisturizers that contain petrolatum, lanolin, dimethicone, or zinc can provide a protective barrier to protect and sooth denuded area.8,10

Use absorbent underpads that wick effluent away from the skin and allow for circulation of air between the patient’s skin and support surface. Avoid use of adult briefs and diapers that trap the moisture against the skin. Change underpads frequently.16

Use absorbent underpads that wick effluent away from the skin and allow for circulation of air between the patient’s skin and support surface. Avoid use of adult briefs and diapers that trap the moisture against the skin. Change underpads frequently.16

Consider application of a fecal containment device or bowel management system.

Consider application of a fecal containment device or bowel management system.

• An external fecal containment device adheres directly to the perianal skin, moving feces away from the skin and into a drainage container. The device can remain in place for 1 to 2 days without leaking.18 If the device is well adhered and not leaking, it may remain in place longer if clinically indicated. Care must be taken during removal of the device to prevent skin trauma or tears.

• The general agreement in the literature is that the perianal incontinence pouch offers many advantages over diapers and balloon rectal catheters and is the least invasive method of fecal containment.11

• Some authors have recommended short-term management of fecal incontinence with devices intended for other purposes.14,16,22 Grogan and Kramer11 studied the use of a nasopharyngeal trumpet inserted into the rectum and then connected to a drainage bag as an effective means to contain fecal material.

• Little research has been conducted to explore or recommend the use of a mushroom catheter with a soft flared tip or balloon-tipped catheter to divert stool.21,22 Correct application of these products is important to prevent trauma to the rectum and internal structures. Adaptation of a device for an unapproved use may be associated with patient injury and concerns of increased liability if a problem arises.22 The clinician should use US Food and Drug Administration (FDA)–approved fecal containment systems rather than adapting devices for management of liquid feces.

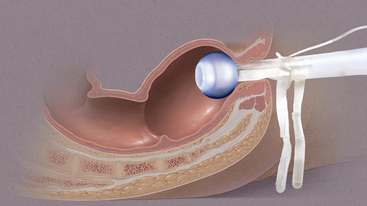

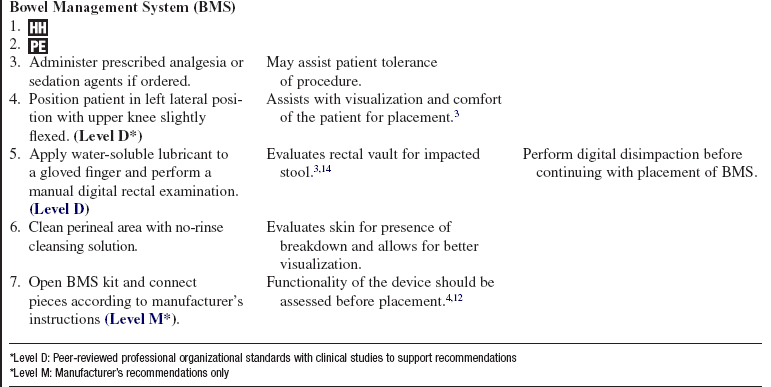

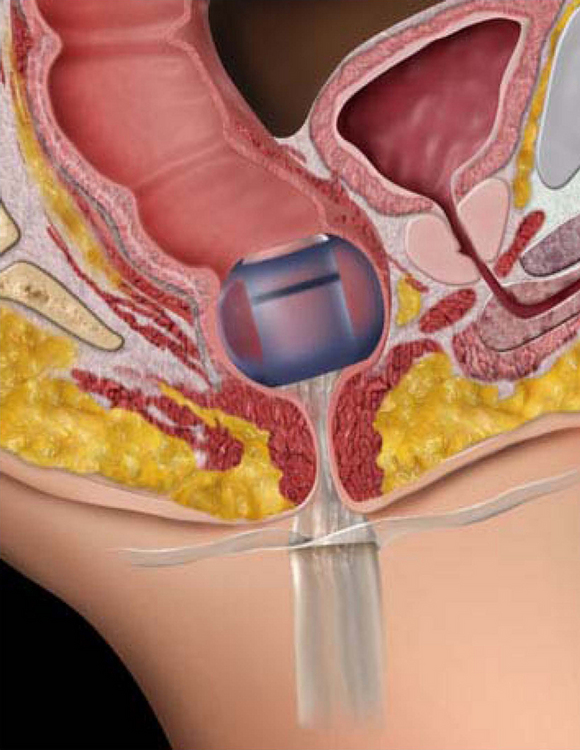

• Bowel management systems (BMS) are FDA-approved devices that may be inserted into the rectal vault for up to 29 days for the diversion of stool into a collection pouch (Figs. 130-1 and 130-2). Early research suggests the device does not harm the rectal mucosa but successfully diverts feces, allowing for perineal skin protection and healing.3,6,14

Manufacturer-specific contraindications for BMS include allergies to product components; children; adults with strictured anal canals; and patients with impactions or recent rectal surgery (less than 6 weeks), severe hemorrhoids, localized inflammatory process or disease, or an incompetent rectal sphincter.4,12

Manufacturer-specific contraindications for BMS include allergies to product components; children; adults with strictured anal canals; and patients with impactions or recent rectal surgery (less than 6 weeks), severe hemorrhoids, localized inflammatory process or disease, or an incompetent rectal sphincter.4,12

The BMS may be inserted to manage existing diarrhea or provide fecal diversion away from existing wounds; however, the stool should be liquid or semiliquid.

The BMS may be inserted to manage existing diarrhea or provide fecal diversion away from existing wounds; however, the stool should be liquid or semiliquid.

Use with caution in patients on anticoagulation therapy or with rectal varices, inflammatory bowel disease, low platelet count, or high international normalized ratio (INR).

Use with caution in patients on anticoagulation therapy or with rectal varices, inflammatory bowel disease, low platelet count, or high international normalized ratio (INR).

• If blood is present in the rectum, ensure there is no evidence of pressure necrosis from the device. Discontinuation of use of the device is recommended if evident. Notify physician for any signs of bleeding.

• Avoid use of ointments or lubricants with petroleum base because they may compromise the integrity of the BMS device.4,12

• Transient fecal incontinence and diarrhea are common among hospitalized patients. Goals of a bowel management program should be clearly discussed among all healthcare providers, patient, and family. Goals should include treatment of the cause of the fecal incontinence if possible and prevention of perineal tissue injury and may not require a containment device.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and rationale for insertion of a BMS.  Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased.

Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased.

• Discuss goals of bowel management program and expected benefits of the intervention.  Rationale: The patient is prepared for placement of the BMS, possible odors, and perineal skin and wound care interventions.

Rationale: The patient is prepared for placement of the BMS, possible odors, and perineal skin and wound care interventions.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Review medical record and discuss medical history with patient for possible contraindications before placement of BMS.  Rationale: Possible complications associated with placement of device are avoided.

Rationale: Possible complications associated with placement of device are avoided.

• Evaluate consistency of fecal contents; contents should be liquid to semiliquid to flow through the BMS.  Rationale: Liquid fecal consistency is important to prevent occlusion of the device.3

Rationale: Liquid fecal consistency is important to prevent occlusion of the device.3

• Assess perineal skin for presence of open areas and pressure ulcers and apply moisture barrier creams.  Rationale: BMS may be used to prevent and treat IAD, and additional skin care products may be indicated to assist in perineal skin healing.22

Rationale: BMS may be used to prevent and treat IAD, and additional skin care products may be indicated to assist in perineal skin healing.22

• Evaluate the patient need for analgesia or sedation.  Rationale: Patient may tolerate procedure more comfortably.

Rationale: Patient may tolerate procedure more comfortably.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Optimize lighting in room and provide privacy for patient.  Rationale: These measures allow for optimal assessment and patient comfort.

Rationale: These measures allow for optimal assessment and patient comfort.

• Place patient in a left lateral position or position of optimal comfort and visualization for anus and rectum.  Rationale: Positioning provides for effective visualization and enhances patient tolerance of procedure.3

Rationale: Positioning provides for effective visualization and enhances patient tolerance of procedure.3

References

1. Ayello, EA, Lyder, CH, Protecting patients from harm . preventing pressure ulcers in hospital patients . Nursing 2007; 37:36–40.

2. Beitz, JM, Fecal incontinence in acutely and critically ill patients. options in management. Ostomy Wound Manage 2006; 52:56–66.

3. Benoit, RA, Watts, C, The effect of a pressure ulcer prevention program and the bowel management system in reducing pressure ulcer prevalence in an ICU setting . JWOCN 2007; 34:163–175.

4. ConvaTec. Flexi-SealTM fecal management system. www.convaTec.com, December 12, 2008. [retrieved].

5. Doughty, DB. Prevention and early detection of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients. JWOCN. 2008; 35:76–78.

6. Echols, J, Friedman, BC, Mullins, RF, et al. Clinical utility and economic impact of introducing a bowel management system. JWOCN. 2007; 34:664–670.

![]() 7. Faria, DT, Shwayder, T, Krull, EA, Perineal skin injury . extrinsic environmental risk factors. Ostomy Wound Manage . 1996; 42:28–37.

7. Faria, DT, Shwayder, T, Krull, EA, Perineal skin injury . extrinsic environmental risk factors. Ostomy Wound Manage . 1996; 42:28–37.

8. Gray, M, Incontinence-related skin damage. essential knowledge. Ostomy Wound Manage 2007; 53:28–31.

9. Gray, M, Bliss, DZ, Doughty, DB, et al, Incontinence-associated dermatitis. a consensus. JWOCN 2007; 34:45–54.

10. Gray, M, Bohacek, L, Weir, D, et al, Moisture vs pressure. making sense out of perineal wounds. JWOCN 2007; 43 :134–142.

![]() 11. Grogan, T, Kramer, D, The rectal trumpet. use of a nasopharyngeal airway to contain fecal incontinence in critically ill patients. JWOCN. 2002; 29(1):193–201.

11. Grogan, T, Kramer, D, The rectal trumpet. use of a nasopharyngeal airway to contain fecal incontinence in critically ill patients. JWOCN. 2002; 29(1):193–201.

12. Hollister, Incorporated, ZassiTM bowel management system. www.holister.com, December 12, 2008 [retrieved].

13. Junkin, J, Selekof, JL, Prevalence of incontinence and associated skin injury in the acute care inpatient . JWOCN 2007; 34:260–269.

14. Keshava, A, Renwick, A, Stewart, P, et al, A nonsurgical means of fecal diversion. the Zassi Bowel Management System. Dis Colon Rectum 2007; 50:1017–1022.

15. Newman, DK, Double taboos. urinary and fecal incontinencethe state of the science. Ostomy Wound Manage 2007; 53:6–7.

16. Nix, D. Prevedntion and treatment of perineal skin breakdown due to incontinence. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2006; 52:26–28.

17. Padula, CA, Osborne, E, Williams, J, Prevention and early detection of pressure ulcers in hospitalized patients . JWOCN 2008; 35:65–75.

![]() 18. Palmieri, B, Benuzzi, Bellini, N, The anal bag. a modern approach to fecal incontinence management. Ostomy Wound Manage 2005; 51:44–52.

18. Palmieri, B, Benuzzi, Bellini, N, The anal bag. a modern approach to fecal incontinence management. Ostomy Wound Manage 2005; 51:44–52.

19. Roach, M, Christie, JA, Fecal incontinence in the elderly . Geriatrics . 2008; 63:13–22.

20. Vollman, KM. Ventilator-associated pneumonia and pressure ulcer prevention as targets for quality improvement in the ICU. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2006; 18:453–467.

![]() 21. Watterworth, B, Ryzeuski, J, Managing fecal incontinence . JWOCN 2005; 32:217–218.

21. Watterworth, B, Ryzeuski, J, Managing fecal incontinence . JWOCN 2005; 32:217–218.

22. Wishin, J, Gallagher, TJ, McCann, E. Emerging options for the management of fecal incontinence in hospitalized patients. JWOCN. 2008; 35:104–110.

23. Zulkowski, K, Perineal dermatitis versus pressure ulcer. distinguishing characteristics. Adv Skin Wound Care 2008; 21:382–388.

Bliss, DZ, Stuart, J, Savik, K, et al. Fecal incontinence in hospitalized patients who are acutely ill. Nurs Res. 2000; 49:101–108.

Gray, M, Ratliff, C, Donovan, A. Perineal skin care for the incontinent patient. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2002; 15:170–177.

Leandefel, CS, Bowers, BJ, Feld, AD, et al, National Institutes of Health State-of-Science Conference Statement . prevention of fecal and urinary incontinence in adults. Ann Intern Med 2008; 148:449–460.