Tracheal Tube Cuff Care

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• The tracheal tube cuff is an inflatable balloon that surrounds the shaft of the tracheal tube near its distal end. When inflated, the cuff presses against the tracheal wall to prevent air leakage and pressure loss from the lungs.

• Appropriate cuff care helps prevent major pulmonary aspirations, prepare for tracheal extubation, decrease the risk of inadvertent extubation, provide a patent airway for ventilation and removal of secretions, and decrease the risk of hospital-acquired infections.

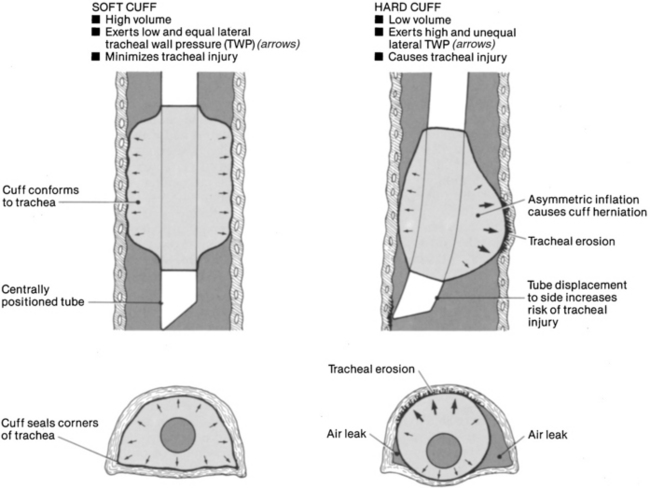

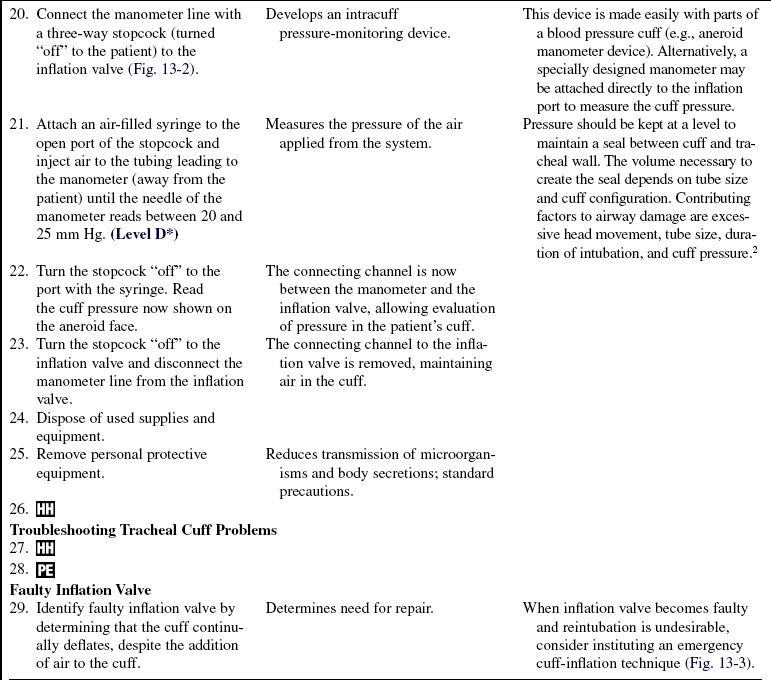

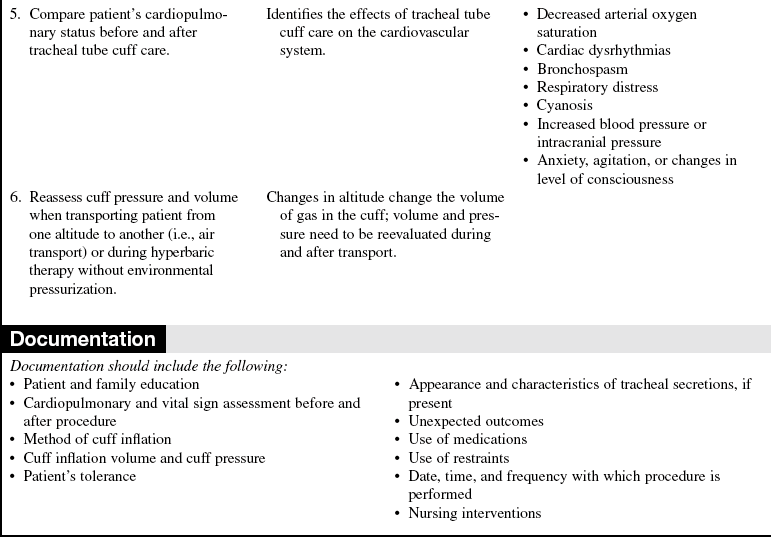

• Although a variety of endotracheal and tracheal tubes exists, the most desirable tube provides a maximum airway seal with minimal tracheal wall pressure, with a high-volume low-pressure cuff (Fig. 13-1). This cuff has a relatively large inflation volume that requires lower filling pressure to obtain a seal (<25 mm Hg or 34 cm H2O). Note: 1 mm Hg = 1.36 cm H2O, or 1 cm H2O = 0.74 mm Hg.

• High-volume low-pressure cuffs allow a large surface area to come into contact with the tracheal wall, distributing the pressure over a much greater area. The older cuff design (low-volume high-pressure) may require 40 mm Hg (54.4 cm H2O) to obtain an effective seal and is undesirable.

• The amount of pressure and volume necessary to obtain a seal and prevent mucosal damage depends on tube size and design, cuff configuration, mode of ventilation, and the patient’s arterial blood pressure.

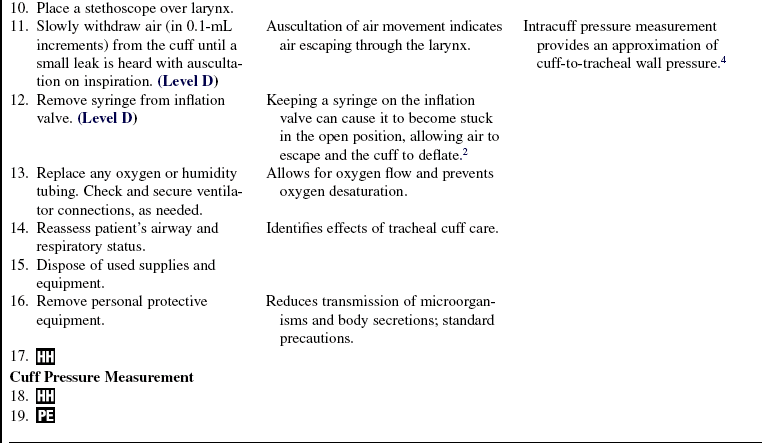

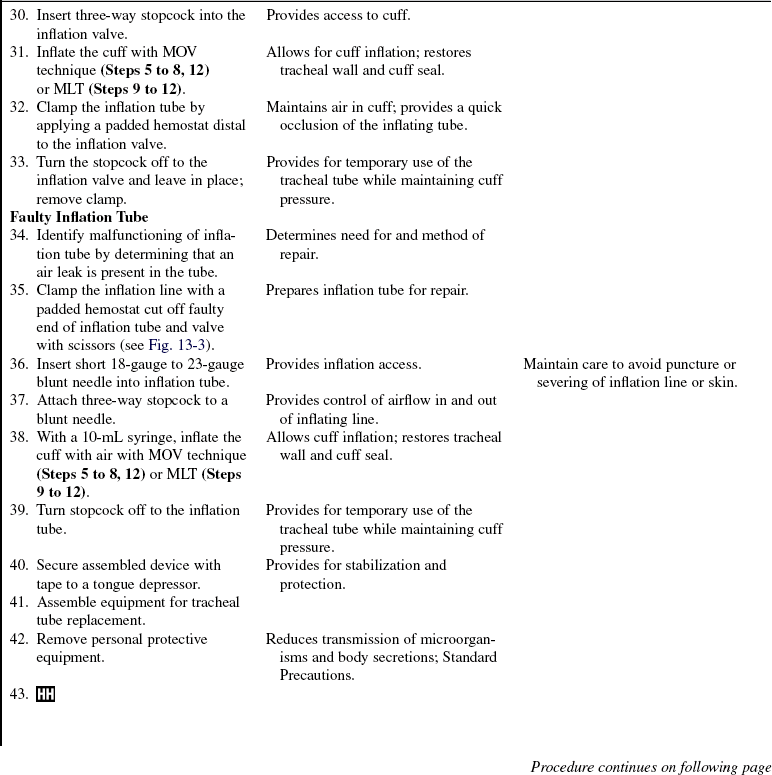

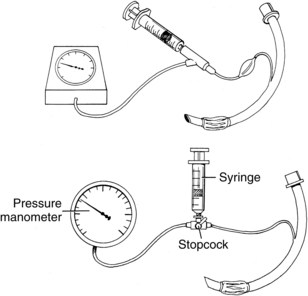

• A variety of devices are available to measure cuff pressures, including bedside sphygmomanometers, special aneroid cuff manometers, and electronic cuff pressure devices. Ideally, the cuff pressures should be between 20 and 25 mm Hg and still meet the goals of cuff use. Tracheal capillary perfusion pressure is 25 to 35 mm Hg for patients with normotensive conditions. Lower cuff pressures are associated with less mucosal damage but also are associated with silent aspiration, which has been shown to be more prevalent at cuff pressures less than 20 mm Hg.1,6,8

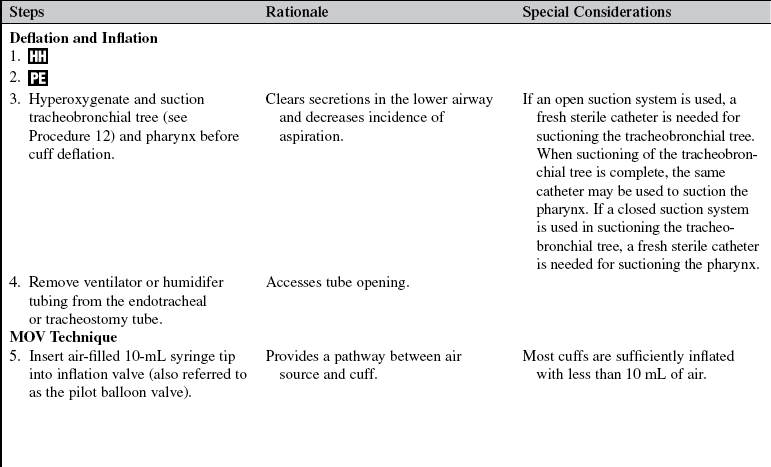

• Two techniques, minimal leak technique (MLT) and minimal occlusion volume (MOV), are used to inflate and monitor air in the cuff.

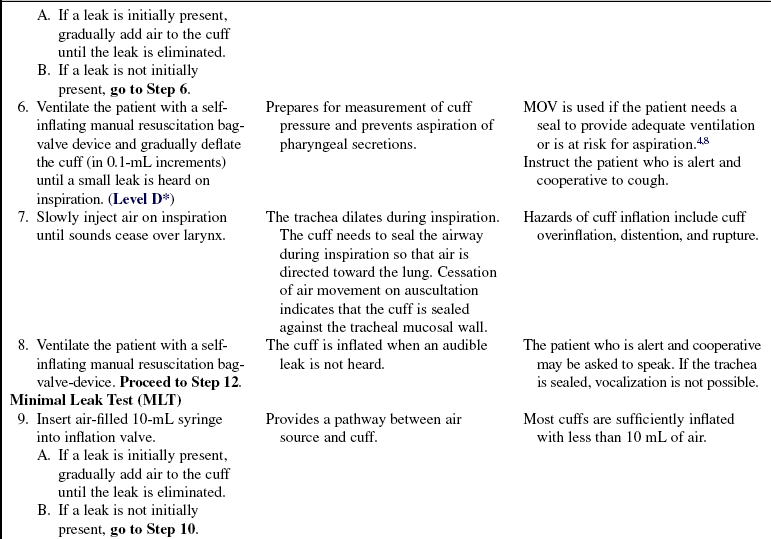

The MLT involves air inflation of the tube cuff until any leak stops; then, a small amount of air is removed slowly until a small leak is heard on inspiration. Problems with this technique include difficulty maintaining positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP), aspiration around the cuff, and increased movement of the tube in the trachea during cuff deflation.2,4,5,7,8 Aspiration may be prevented with deep pharyngeal suctioning before use of the MLT.

The MLT involves air inflation of the tube cuff until any leak stops; then, a small amount of air is removed slowly until a small leak is heard on inspiration. Problems with this technique include difficulty maintaining positive end expiratory pressure (PEEP), aspiration around the cuff, and increased movement of the tube in the trachea during cuff deflation.2,4,5,7,8 Aspiration may be prevented with deep pharyngeal suctioning before use of the MLT.

The MOV consists of injection of air into the cuff until no leak is heard, then withdrawal of the air until a small leak is heard on inspiration, and then addition of more air until no leak is heard on inspiration.2,4,5,7,8

The MOV consists of injection of air into the cuff until no leak is heard, then withdrawal of the air until a small leak is heard on inspiration, and then addition of more air until no leak is heard on inspiration.2,4,5,7,8

• Each technique has distinct advantages. MLT decreases tracheal mucosal injury and assists in mobilizing secretions forward into the pharynx. MOV is used if the patient needs a seal to provide adequate ventilation or is at risk for aspiration.4,8

• Although rare since the use of high-volume low-pressure devices became common, the adverse effects of tracheal tube cuff inflation include tracheal stenosis, necrosis, tracheoesophageal fistulas, and tracheomalacia. These complications may be more likely to occur in conditions that adversely affect tissue response to mucosal injury, such as hypotension. Two major mechanisms are mainly responsible for airway damage: tube movement and pressure. Duration of intubation also plays a significant role.4,8

• Routine cuff deflation is unnecessary and is no longer recommended.4

• Unintentional extubation and tube manipulation can occur with ineffective patient restraint or sedation, inadequate securing of the tube, incorrect tube size and length, improper support or respiratory underinflation of endotracheal cuff, and prolonged intubation.4

EQUIPMENT

• Pressure manometer with extension line or specially designed manometer to measure cuff pressures

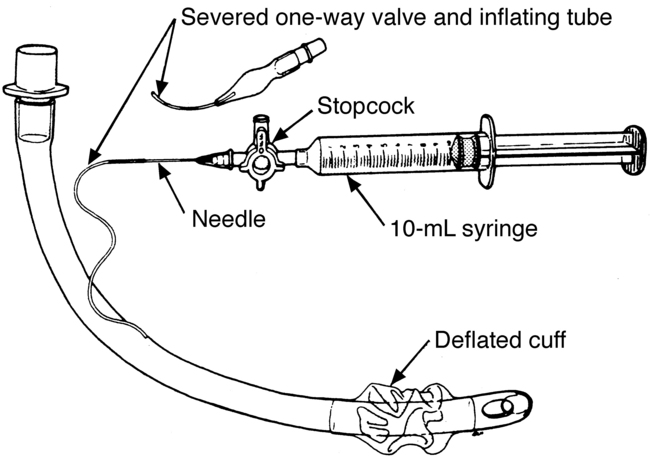

Additional equipment (for cuff inflation with faulty inflating device) includes the following:

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure (if patient condition and time allow) and the reason for tracheal tube cuff care.  Rationale: This communication identifies patient and family knowledge deficits concerning the patient’s condition, procedure, expected benefits, and potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and voice concerns. Explanations decrease patient anxiety and enhance cooperation.

Rationale: This communication identifies patient and family knowledge deficits concerning the patient’s condition, procedure, expected benefits, and potential risks and allows time for questions to clarify information and voice concerns. Explanations decrease patient anxiety and enhance cooperation.

• Explain the patient’s role in assisting with cuff care.  Rationale: This information elicits patient cooperation.

Rationale: This information elicits patient cooperation.

• Explain that the procedure can be uncomfortable and cause the patient to cough.  Rationale: This explanation elicits patient cooperation.

Rationale: This explanation elicits patient cooperation.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Assess presence of bilateral breath sounds.  Rationale: This assessment assists in verification of tube placement.

Rationale: This assessment assists in verification of tube placement.

• Assess signs and symptoms of cuff leakage, as follows:

Audible or auscultated inspiratory leak over larynx

Audible or auscultated inspiratory leak over larynx

Patient able to vocalize audibly

Patient able to vocalize audibly

Inflation (pilot) valve balloon deflation

Inflation (pilot) valve balloon deflation

Loss of inspiratory and expiratory volume on patient with mechanical ventilation

Loss of inspiratory and expiratory volume on patient with mechanical ventilation  Rationale: An adequate seal of cuff to tracheal wall does not permit air to flow past the cuff.

Rationale: An adequate seal of cuff to tracheal wall does not permit air to flow past the cuff.

• Assess signs and symptoms of inadequate ventilation, as follows:

Rising arterial carbon dioxide tension

Rising arterial carbon dioxide tension

Patient-ventilator dyssynchrony

Patient-ventilator dyssynchrony

Increasing (early sign) or decreasing (late sign) arterial blood pressure

Increasing (early sign) or decreasing (late sign) arterial blood pressure

Activation of expiratory or inspiratory volume alarms on mechanical ventilator

Activation of expiratory or inspiratory volume alarms on mechanical ventilator  Rationale: Inadequate ventilation results when cuff seal is improper or cuff leak is extensive.

Rationale: Inadequate ventilation results when cuff seal is improper or cuff leak is extensive.

• Assess amount of air or pressure previously used to inflate the cuff.  Rationale: The amount of air previously used to inflate the cuff can be used as a guideline to determine changes in volume or pressure or both.

Rationale: The amount of air previously used to inflate the cuff can be used as a guideline to determine changes in volume or pressure or both.

• Assess size of tracheal tube and size of patient.  Rationale: Volume and pressure of air needed to seal the airway depend on the relationship of tube and trachea diameters.

Rationale: Volume and pressure of air needed to seal the airway depend on the relationship of tube and trachea diameters.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Place patient in semi-Fowler’s position.  Rationale: This positioning promotes general relaxation, oxygenation, and ventilation. It also reduces stimulation of the gag reflex and risk of aspiration.

Rationale: This positioning promotes general relaxation, oxygenation, and ventilation. It also reduces stimulation of the gag reflex and risk of aspiration.

References

1. Hess, D. Tracheostomy tubes and related appliances. Respir Care. 2005; 50(4):497–509.

2. MacIntyre, N, Branson, R. Mechanical ventilation,, ed 2. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2009.

3. Morris, L, Zoumalan, R, Roccaforte, D, et al, Monitoring -tracheal tube cuff pressures in the intensive care unit. a comparison of digital palpation and manometry. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 2007; 116(9):639–642.

4. Pierce, L, Airway maintenance. Management of the mechanically ventilated patient. ed 2. Saunders, St Louis, 2007.

![]() 5. Plambeck, A, Adult ventilation management. Corexcel. www.corexcel.com/courses/vent.htm, 2004 [retrieved April 22, 2004].

5. Plambeck, A, Adult ventilation management. Corexcel. www.corexcel.com/courses/vent.htm, 2004 [retrieved April 22, 2004].

6. Roman, M. Tracheostomy tubes. Medsurg Nurs. 2005; 14(2):143–145.

7. St John R, Protocols for practice. airway management. Crit Care Nurse. 2004; 24(2):93–96.

8. Urden, L, Stacy, K, Lough, M, et al, Thelan’s critical -care nursing. diagnosis and management. Mosby, St Louis, 2005.