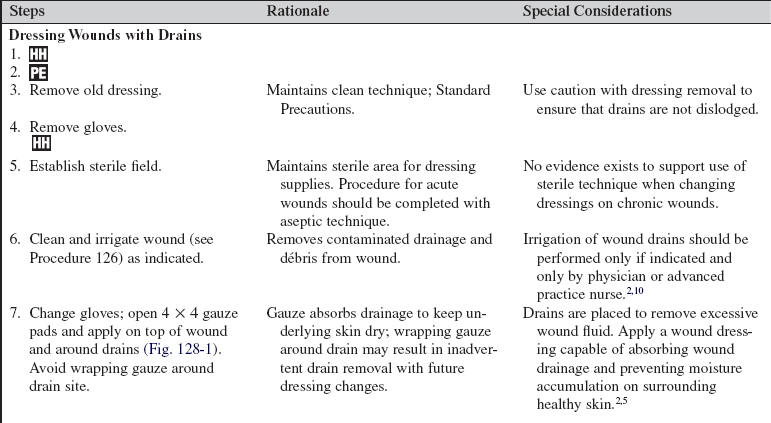

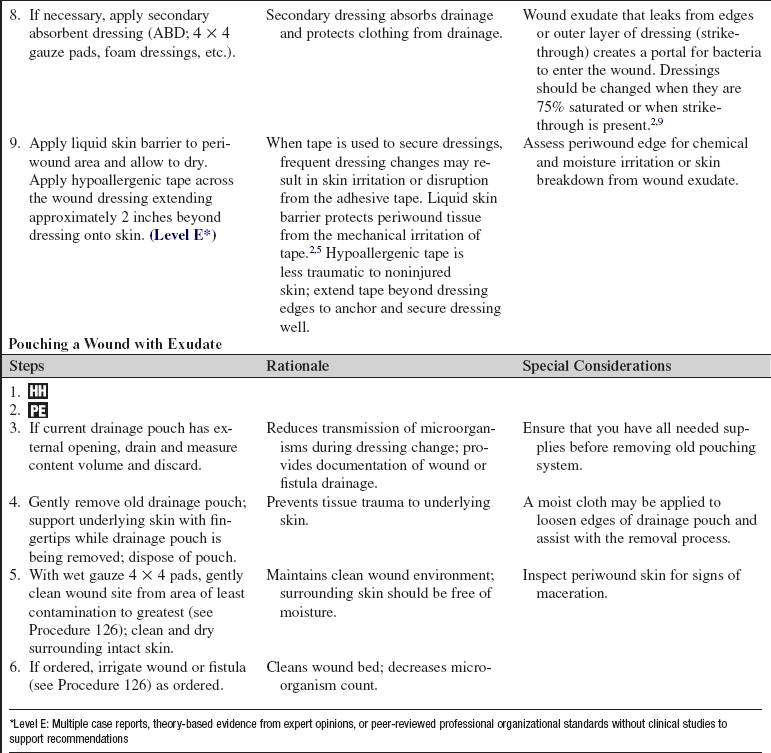

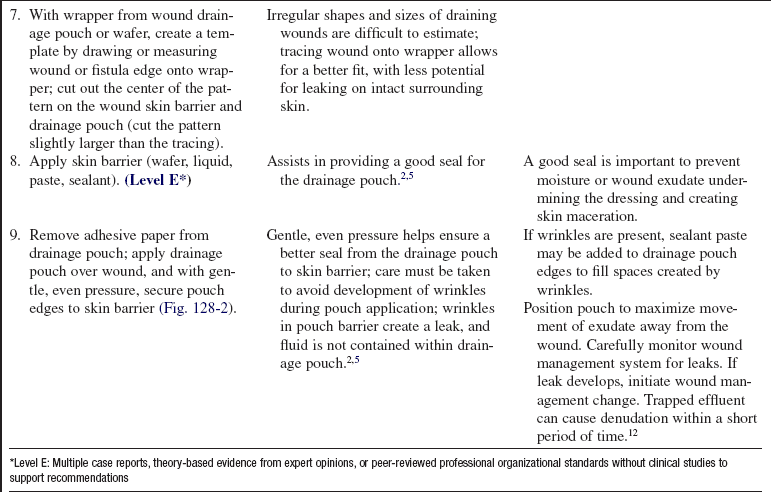

Wound Management with Excessive Drainage

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

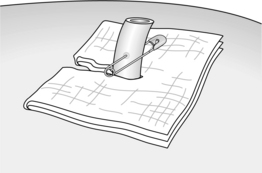

• Wound exudate is produced in response to the inflammatory phase of the healing process. As wounds heal, the amount of exudate should diminish. Chronic, nonhealing wounds may produce exudate for prolonged periods of time, necessitating effective management of the fluid.1,2,7,9–11

• Goals of wound care must be clearly identified so that proper wound care products are used.10 Wound healing is best achieved through adequate cleansing, débridement, and dressing of the wound bed on the basis of wound characteristics.

• Excessive wound fluid may create pressure in the wound bed and compromise perfusion. Excessive moisture may cause periwound tissue damage and extend the wound or skin injury.5,6

• Assessment of wound exudate should include the quantity, color, consistency, and odor of drainage. When changes in wound exudate occur, the cause should be explored. These changes along with other clinical signs and symptoms may indicate possible increase in bacterial burden or infection.

• Drains are placed in wounds to facilitate healing by providing an exit for excessive fluid accumulating in or near the wound bed. Most wound drains are surgically placed; drains may or may not be secured with sutures.

• Excessive wound fluid may provide a source for proliferation of microorganisms. Wound drains may be ports of microorganism entry; aseptic techniques must be strictly observed.

• Pouching is an effective means of collecting wound and fistula drainage.3,8 Suction may be used with pouching systems to pull fluid away from the wound bed.5

• Excessive wound drainage is removed to allow for wound healing to occur without tissue congestion, microorganism proliferation, and skin maceration.

• Excessive wound drainage may need to be calculated into the assessment of a patient’s daily intake and output.

• Negative-pressure wound therapy (see Procedure 131) stimulates tissue growth and promotes wound healing. The closed system also provides active withdrawal of excessive wound fluid to assist in the management of exudating wounds.4

• Assess the patient’s nutritional needs, specifically for protein, with exudating wounds.

• Excessive wound exudate production may result in the loss of up to 100 g of protein daily in wound exudate.2,9 Nutritional supplementation of protein is necessary for wound healing.

EQUIPMENT

• Nonsterile and sterile gloves; sterile field

• Personal protective equipment: gowns and face protection

• Sterile gauze (4 × 4 pads); abdominal pad (e.g., ABD) or other absorptive dressings may be needed

• Sterile water or normal saline (NS) solution for cleansing

• Liquid skin barrier, skin barrier wafers, paste, powder and sealant, or hydrocolloid to protect periwound surface

• Drainage bag or pouch: ostomy-type appliance

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and the reason for changing wound dressing; educate regarding potential odor during the procedure.  Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased.

Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased.

• Discuss patient’s role in dressing change procedure and maintenance of wound drains or pouches.  Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited; patient is prepared for wound management on discharge.

Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited; patient is prepared for wound management on discharge.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Monitor for signs and symptoms of wound infection, including the following:

Elevated temperature and white blood cell count

Elevated temperature and white blood cell count

Changes in wound drainage: amount, color, odor

Changes in wound drainage: amount, color, odor

Increased pressure or tenderness at wound site

Increased pressure or tenderness at wound site

Rationale: Early detection of infection facilitates prompt and appropriate interventions.

Rationale: Early detection of infection facilitates prompt and appropriate interventions.

• Assess patency of wound drainage system.  Rationale: Drains are frequently soft and pliable and thus can easily become kinked or blocked if wound drainage is fibrous in composition. Pouches with drainage systems may also become blocked with fibrous wound drainage; patency of the system is needed to ensure the wound drainage system moves exudate away from the wound.

Rationale: Drains are frequently soft and pliable and thus can easily become kinked or blocked if wound drainage is fibrous in composition. Pouches with drainage systems may also become blocked with fibrous wound drainage; patency of the system is needed to ensure the wound drainage system moves exudate away from the wound.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Follow institutional standard for assessing pain. Administer analgesia as prescribed.  Rationale: Identifies need for pain interventions.

Rationale: Identifies need for pain interventions.

• Place patient in position of optimal comfort and visualization for dressing the wound.  Rationale: Positioning provides for effective wound visualization and enhances patient tolerance of procedure.

Rationale: Positioning provides for effective wound visualization and enhances patient tolerance of procedure.

• Optimize lighting in room and provide privacy for patient.  Rationale: These measures allow for optimal wound assessment and patient comfort.

Rationale: These measures allow for optimal wound assessment and patient comfort.

Figure 128-1 Dressing a wound with a drain.

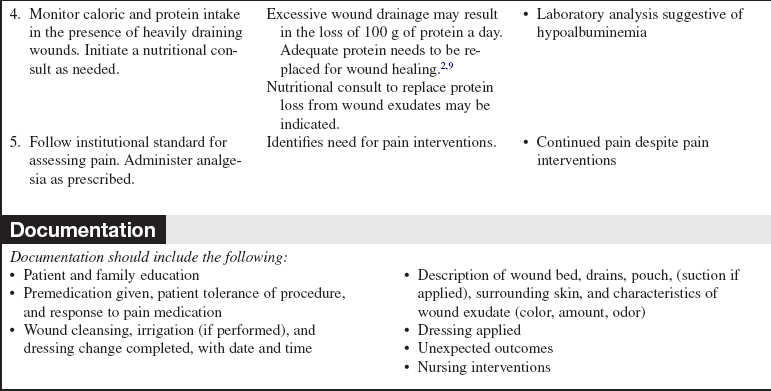

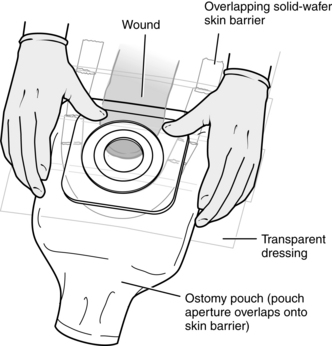

Figure 128-2 Pouching a wound.

References

1. Ayello, EA, The TIME principles of wound bed preparation . Adv Skin Wound Care. 2009; 22(Suppl 1):2–5.

2. Bates-Jensen BM, Ovington, L, Management of exudate and infectionSussman C, Bates-Jensen BM, eds.. Wound care . a collaborative practice manual. ed 3. 2007. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins: Philadelphia :215–233.

3. Bates-Jensen BM, Seaman, S, Management of malignant cutaneous wounds and fistulas. Sussman, C. Bates-Jensen, BM. Wound care . a collaborative practice manual. ed 3. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, Philadelphia, 2007:476–494.

4. Bovill, E, et al, Topical negative pressure wound therapy. a review of its role and guidelines for its use in the management of acute wounds. Int Wound J. 2008; 65(3):722–731.

5. Bryant, RA, Rolstad, BS, Management of drain sites and fistulasBryant RA, Nix DP, eds.. Acute & chronic wounds . current management concepts. ed 3. Mosby, Philadelphia, 2007:490–516.

6. Gray, M, Weir, D, Prevention and treatment of moisture-associated skin damage (maceration) in the periwound skin. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2007; 34(2):153–157.

![]() 7. Hanson, D, et al. Understanding wound fluid and the phases of healing. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005; 18(1):360–362.

7. Hanson, D, et al. Understanding wound fluid and the phases of healing. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2005; 18(1):360–362.

8. Naude, L, Exudate management. putting the patient first. Pro Nurs Today. 2008; 12(5):29–32.

9. Nix, DP, Patient assessment and evaluation of healing Bryant RA, Nix DP, eds. Acute & chronic wounds: current management concepts, ed 3, Philadelphia: Mosby, 2007.

![]() 10. Ovington, LG, Dealing with drainage. the what, why, and how of wound exudates. Home Healthcare Nurse 2002; 20:368–374.

10. Ovington, LG, Dealing with drainage. the what, why, and how of wound exudates. Home Healthcare Nurse 2002; 20:368–374.

11. Rolstad, BS, Ovington, LG, Principles of wound management Bryant RA, Nix DP, eds.. Acute & chronic wounds: current management concepts. ed 3. Mosby, Philadelphia, 2007:391–426.

12. Brindle, CT, Blankenship, J. Management of complex abdominal wounds with small bowel fistulae; isolation techniques and exudate control to improve outcomes. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurs. 2009; 36(4):396–404.

Hocevar, BJ, et al, Management of fistula in the abdominal region. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nursing . 2008; 35(4):417–423.

Skovgaard, R, Keiding, H, A cost-effectiveness analysis of fistula treatment in the abdominal region using a new integrated fistula and wound management system. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nursing . 2008; 35(6):592–595.

Trevillion, N. Cleaning wounds with saline or tap water. Emerg Nurse. 2008; 16(2):24–26.