Débridement: Pressure Ulcers, Burns, and Wounds

Débridement: Pressure Ulcers, Burns, and Wounds

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Before wound débridement, the patient and wound should be assessed for underlying causes, patient’s physical condition, nutritional status, and current healthcare treatment plan, including medications.3

• Normal wound healing progresses through an orderly sequence of three overlapping phases: inflammation, proliferation, and reepithelialization and remodeling.

• The presence of necrotic tissue or debris interrupts the normal sequence of wound healing, retards healing processes, and provides a medium that promotes bacterial growth.4

• Acute wounds may be classified as either partial-thickness or full-thickness wounds. Partial-thickness wounds penetrate the epidermis and part of the dermis; partial-thickness wounds can be further described as superficial or deep partial-thickness wounds. Full-thickness wounds extend to all skin layers, the epidermis and dermis, and may penetrate subcutaneous tissues.3

• Pressure ulcers are defined as localized injury to the skin or underlying tissue usually over a bony prominence as a result of pressure.7 The National Pressure Ulcer Advisory Panel (NPUAP) staging system is used to describe pressure ulcers.1,7

Stage I: Intact skin with nonblanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching, but the area may differ in color from surrounding tissues.7

Stage I: Intact skin with nonblanchable redness of a localized area usually over a bony prominence. Darkly pigmented skin may not have visible blanching, but the area may differ in color from surrounding tissues.7

Stage II: Presents as partial-thickness loss of dermis as a shallow open ulcer with a red-pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled blister.7

Stage II: Presents as partial-thickness loss of dermis as a shallow open ulcer with a red-pink wound bed, without slough. May also present as an intact or open/ruptured serum-filled blister.7

Stage III: Is described as full-thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible; however, bone, tendon, and muscle are not exposed. Undermining and tunneling may also be present, as well as slough.7

Stage III: Is described as full-thickness tissue loss. Subcutaneous fat may be visible; however, bone, tendon, and muscle are not exposed. Undermining and tunneling may also be present, as well as slough.7

Stage IV: Presents as a full-thickness tissue injury to include exposed bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some parts of the wound bed.

Stage IV: Presents as a full-thickness tissue injury to include exposed bone, tendon, or muscle. Slough or eschar may be present on some parts of the wound bed.

Unstageable: Tissue injury that cannot be adequately assessed because of the slough or eschar covering the wound base. Wound débridement should occur before staging the tissue injury.1,7

Unstageable: Tissue injury that cannot be adequately assessed because of the slough or eschar covering the wound base. Wound débridement should occur before staging the tissue injury.1,7

Suspected deep tissue injury: A purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister from damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure or shear. The area may be painful, boggy, warmer, or cooler as compared with adjacent tissue.7

Suspected deep tissue injury: A purple or maroon localized area of discolored intact skin or blood-filled blister from damage of underlying soft tissue from pressure or shear. The area may be painful, boggy, warmer, or cooler as compared with adjacent tissue.7

• Necrotic tissue is nonviable tissue and may range in color from whitish gray, tan, yellow, and finally progressing to black. Necrotic tissue nourishes bacteria and slows healing by retarding the inflammatory phase.4 It may lead to deeper penetration of bacteria into tissues, resulting in cellulites, osteomyelitis, and possible limb loss.5

• Débridement provides a mechanism of removal of necrotic tissue and reestablishes normal phases of wound healing.

• Vascular evaluation is essential before wound débridement. Inadequate perfusion may result in the wound extending into a deeper dermal or full-thickness wound after débridement.9 Pressure ulcers, burns, and chronic wounds may develop necrotic tissue that requires débridement for wound healing to progress.

• Débridement may be achieved with several methods2:

Surgical débridement: Fast and effective means of removal of devitalized tissue. Requires local anesthesia, use of sterile instruments, and conditions and availability of a qualified clinician.2,9 Large amounts of necrotic tissue may be removed. This may be considered in burn patients with large amounts of eschar or with necrotizing soft tissue infections (i.e., necrotizing fasciitis).5

Surgical débridement: Fast and effective means of removal of devitalized tissue. Requires local anesthesia, use of sterile instruments, and conditions and availability of a qualified clinician.2,9 Large amounts of necrotic tissue may be removed. This may be considered in burn patients with large amounts of eschar or with necrotizing soft tissue infections (i.e., necrotizing fasciitis).5

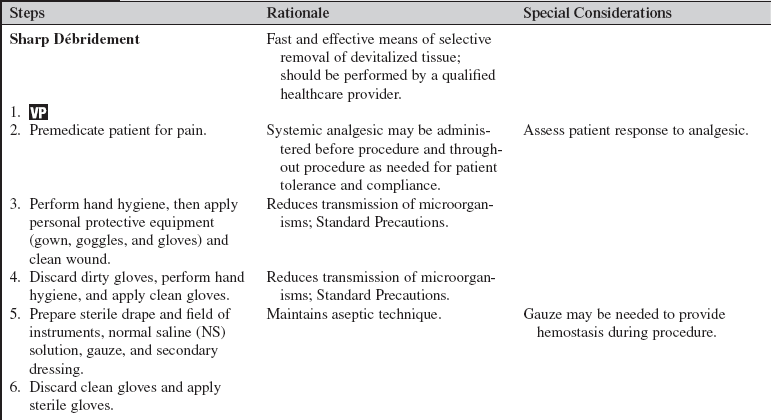

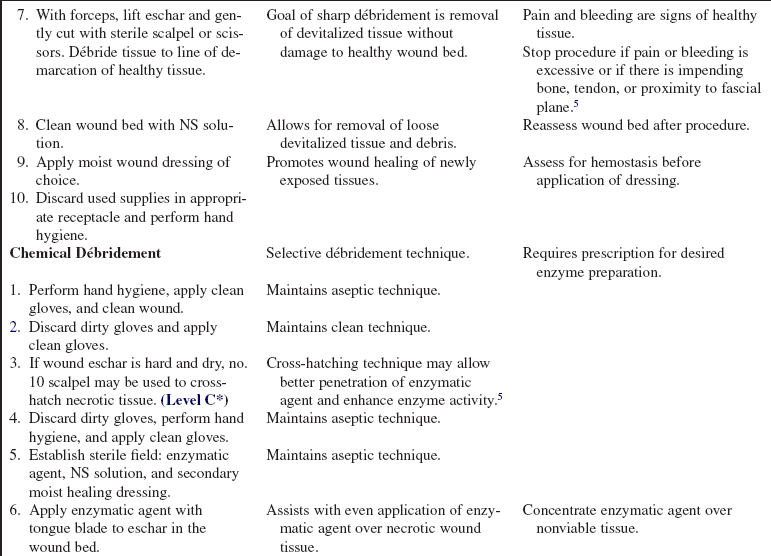

Sharp débridement: Similar to surgical debridement, but local anesthesia may or may not be administered. Sharp débridement procedures should be performed only by qualified physicians, advanced practice nurses, and other healthcare providers (including critical care nurses) with additional knowledge, skills, and demonstrated competence per professional licensure or institutional standard.2,9 This kind of débridement may be done at the bedside, in a clinic, or at an office. Sharp débridement is best for adherent dry eschar with or without infection present. The bacterial count is rapidly reduced.4 Sharp débridement may be difficult on hard, dry wounds. Consider enzymatic débridement as first option.9 Sharp débridement should be discontinued in presence of pain, bleeding, or exposure of underlying structures.

Sharp débridement: Similar to surgical debridement, but local anesthesia may or may not be administered. Sharp débridement procedures should be performed only by qualified physicians, advanced practice nurses, and other healthcare providers (including critical care nurses) with additional knowledge, skills, and demonstrated competence per professional licensure or institutional standard.2,9 This kind of débridement may be done at the bedside, in a clinic, or at an office. Sharp débridement is best for adherent dry eschar with or without infection present. The bacterial count is rapidly reduced.4 Sharp débridement may be difficult on hard, dry wounds. Consider enzymatic débridement as first option.9 Sharp débridement should be discontinued in presence of pain, bleeding, or exposure of underlying structures.

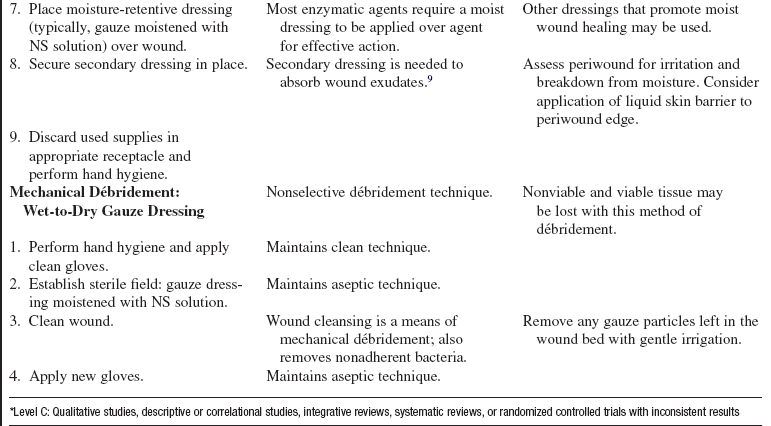

Chemical (enzymatic) débridement: Highly selective method of removal of necrotic tissue. Relies on naturally occurring enzymes that are exogenously applied to the wound surface to degrade tissue. This is a slower process that requires a moist wound bed with adequate secondary dressing to absorb wound exudate. Enzymatic débriding agents may be selective or nonselective to viable tissues. Nonselective agents may be best for thick, leathery, adherent eschar. Selective agents may be best when excess protein buildup is present.6 Examples of wounds that may benefit from chemical débridement are a partial-thickness burn wound or unstageable pressure ulcer.

Chemical (enzymatic) débridement: Highly selective method of removal of necrotic tissue. Relies on naturally occurring enzymes that are exogenously applied to the wound surface to degrade tissue. This is a slower process that requires a moist wound bed with adequate secondary dressing to absorb wound exudate. Enzymatic débriding agents may be selective or nonselective to viable tissues. Nonselective agents may be best for thick, leathery, adherent eschar. Selective agents may be best when excess protein buildup is present.6 Examples of wounds that may benefit from chemical débridement are a partial-thickness burn wound or unstageable pressure ulcer.

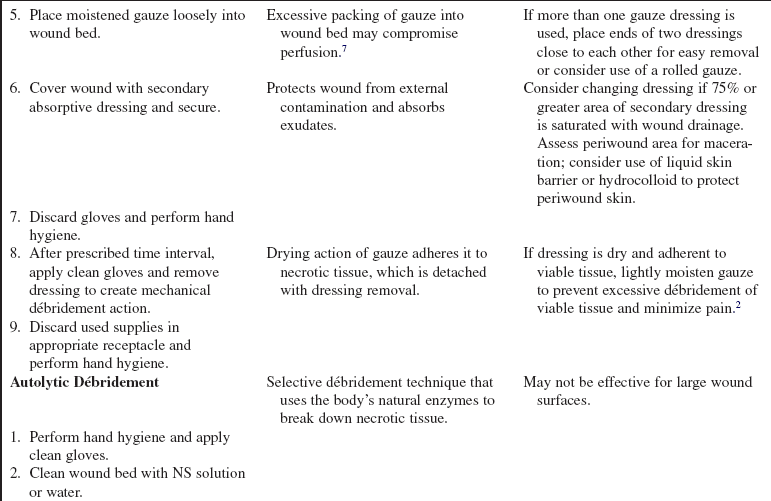

Mechanical débridement: Method of physical removal of debris from the wound. Methods range from wet-to-dry gauze dressings, irrigation, pulsatile lavage, and whirlpool therapy. Débridement is nonselective, and healthy tissue and necrotic tissue and debris may be removed in the process, causing bleeding and pain.

Mechanical débridement: Method of physical removal of debris from the wound. Methods range from wet-to-dry gauze dressings, irrigation, pulsatile lavage, and whirlpool therapy. Débridement is nonselective, and healthy tissue and necrotic tissue and debris may be removed in the process, causing bleeding and pain.

Autolytic débridement: Uses the properties of moisture-interactive dressings to facilitate digestion of devitalized tissue by the body’s own enzymes. Typically, if tissue autolysis does not begin to appear in the wound in 24 to 72 hours, another method of débridement should be considered.2

Autolytic débridement: Uses the properties of moisture-interactive dressings to facilitate digestion of devitalized tissue by the body’s own enzymes. Typically, if tissue autolysis does not begin to appear in the wound in 24 to 72 hours, another method of débridement should be considered.2

Physicians, advanced practice nurses, or physician extenders who have demonstrated knowledge and competency should perform surgical débridement.

Physicians, advanced practice nurses, or physician extenders who have demonstrated knowledge and competency should perform surgical débridement.

• Sharp débridement should be performed by physicians, advanced practice nurses, registered nurses, and physical therapists with documented educational course completion and validation of knowledge and skill. One should check with state regulatory agencies before performing sharp wound débridement.10

• A key to successful safe sharp débridement is assessment and knowledge of anatomy.5 All wound care procedures should adhere to principles of aseptic technique.

• Clinical judgment should be used in determining whether clean or sterile technique is indicated in the wound dressing procedure. Generally speaking, acute wounds may be cared for with sterile technique and chronic wounds may be cared for with clean technique.1 The clinician must assess the patient, type or stage of wound, and type of procedure in deciding which technique should be used in wound care.

EQUIPMENT

Personal protective equipment (gown, goggles, mask)

Personal protective equipment (gown, goggles, mask)

Normal saline solution or water to clean wound

Normal saline solution or water to clean wound

Clean gloves or sterile gloves (depending on type and age of wound)

Clean gloves or sterile gloves (depending on type and age of wound)

Enzymatic preparation or solution (prescribed)

Enzymatic preparation or solution (prescribed)

Filler dressing if needed; secondary absorptive dressing

Filler dressing if needed; secondary absorptive dressing

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Vascular assessment should be completed before débridement.  Rationale: Poor perfusion may result in the extension of the wound after débridement.

Rationale: Poor perfusion may result in the extension of the wound after débridement.

• Assess tissues or underlying structures before sharp débridement.  Rationale: Sharp débridement is contraindicated if underlying structures such as muscle, bone, tendon, and blood vessels may be exposed.

Rationale: Sharp débridement is contraindicated if underlying structures such as muscle, bone, tendon, and blood vessels may be exposed.

• Assess for signs and symptoms of local and systemic infection.  Rationale: Débridement may seed bacteria into systemic circulation; appropriate antibiotics should be considered before débridement in at-risk patient populations.8 Surgical débridement, the most aggressive type of débridement, is the method of choice when signs of severe cellulitis or sepsis are present.1

Rationale: Débridement may seed bacteria into systemic circulation; appropriate antibiotics should be considered before débridement in at-risk patient populations.8 Surgical débridement, the most aggressive type of débridement, is the method of choice when signs of severe cellulitis or sepsis are present.1

• Ensure that coagulation parameters are within normal limits.  Rationale: Coagulation abnormalities may result in unwanted bleeding complications from the débridement process.

Rationale: Coagulation abnormalities may result in unwanted bleeding complications from the débridement process.

• Assess the patient for pain and consider premedication.  Rationale: Medication decreases patient discomfort.

Rationale: Medication decreases patient discomfort.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers. Obtain informed consent for surgical and sharp débridement.2,11  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention. Informed consent ensures patient knowledge of procedure.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention. Informed consent ensures patient knowledge of procedure.

• Before the procedure, comply with Universal Protocol requirements.11 Ensure all relevant studies and documents, including informed consent, are available. Ensure site markings have been made where appropriate. Prior to surgical or sharp débridement, perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Premedicate patient with prescribed analgesic, if needed. Assess patient’s response to analgesic before start of procedure. Reassess patient’s need for additional analgesic agents throughout débridement procedure. Consider topical lidocaine solution.  Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased. Pain results in vasoconstriction of the cutaneous tissues from the increase in adrenergic activity. Adequate pain control improves tissue perfusion and results in improved healing.3

Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased. Pain results in vasoconstriction of the cutaneous tissues from the increase in adrenergic activity. Adequate pain control improves tissue perfusion and results in improved healing.3

• Place patient in position of optimal comfort and visualization for dressing the wound. Keep the patient warm while the wound is exposed.  Rationale: Positioning provides for effective wound visualization and enhances patient tolerance of procedure. Keeping the patient warm prevents vasoconstriction that impairs wound healing.

Rationale: Positioning provides for effective wound visualization and enhances patient tolerance of procedure. Keeping the patient warm prevents vasoconstriction that impairs wound healing.

• Optimize lighting in room and provide privacy for patient.  Rationale: Optimal wound assessment and patient comfort are provided.

Rationale: Optimal wound assessment and patient comfort are provided.

References

![]() 1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Treatment of pressure ulcers. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and -Human Services; 1994. [AHCPR Publication No. 95-0652].

1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research. Treatment of pressure ulcers. Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and -Human Services; 1994. [AHCPR Publication No. 95-0652].

2. Anderson, I. Debridement methods in wound care. Nurs Stand. 2006; 20(24):65–72.

3. Broughton, G, et al, Wound healing. an overview. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 2006; 117(7S):1e-s–32e-s.

4. Calianno, C, et al, Wound bed preparation. laying the foundation for treating chronic wounds, part 1. Wound Skin Care. 2006; 36(2):70.

5. Kirshen, C, et al, Debridement. a vital component of wound bed preparation. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2006; 19(9):506–517.

6. Kravitz, S, et al, Management of skin ulcers. understanding the mechanism and selection of enzymatic debriding agents. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2008; 21(2):72–74.

7. NPUAP. Pressure ulcer stages revised. www.npuap.org, September 24, 2008. [retrieved from].

![]() 8. Ovington, LG. Hanging wet-to-dry dressings out to dry. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2002; 15:79–89.

8. Ovington, LG. Hanging wet-to-dry dressings out to dry. Adv Skin Wound Care. 2002; 15:79–89.

![]() 9. Rodeheaver, GT, Pressure ulcer debridement and cleansing. a review of current literature. Ostomy Wound Manage 1999; 45:80–86.

9. Rodeheaver, GT, Pressure ulcer debridement and cleansing. a review of current literature. Ostomy Wound Manage 1999; 45:80–86.

![]() 10. Thomaselli, N, WOCN position statement. conservative sharp wound debridement for registered nurses. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses 1995; 22:32A.

10. Thomaselli, N, WOCN position statement. conservative sharp wound debridement for registered nurses. J Wound Ostomy Continence Nurses 1995; 22:32A.

![]() 11. The Joint Commission. Universal protocol for preventing wrong site, wrong procedure, wrong person surgery. www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/UniversalProtocol, 2003. [retrieved January 8, 2009, from].

11. The Joint Commission. Universal protocol for preventing wrong site, wrong procedure, wrong person surgery. www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/UniversalProtocol, 2003. [retrieved January 8, 2009, from].

Dryburgh, N, Smith, F, Donaldson, J, et al, Debridement for surgical wounds. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008(3), doi: 10. 1002/14651858. [CD006214].

Byrant, RA, Nix, CP, Acute and chronic wounds. ed 3. Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2007.

Siegel, JD, Rhinehart, E, Jackson, M, et al. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 2007.

Sussman, C, Fowler, E, Wethe, J. Sharp debridement of wounds . Torrance, CA: Sussman Physical Therapy, Inc; 1995.

Rationale: Explanation decreases patient anxiety and comfort and informs patient.

Rationale: Explanation decreases patient anxiety and comfort and informs patient.