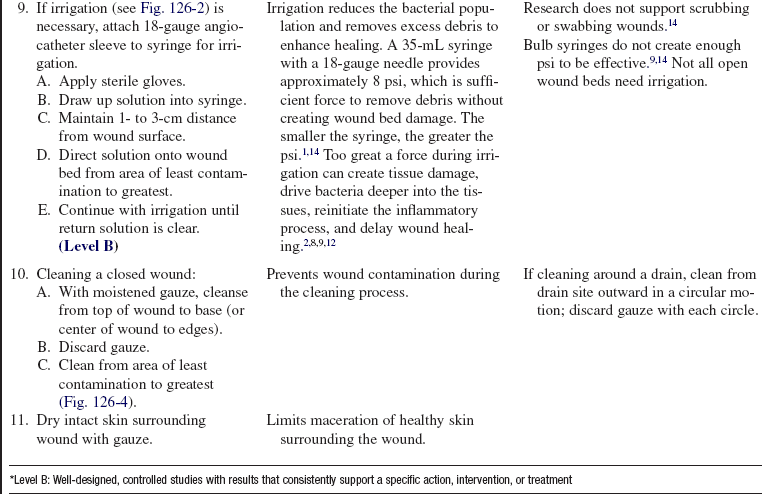

Cleaning, Irrigating, Culturing, and Dressing an Open Wound

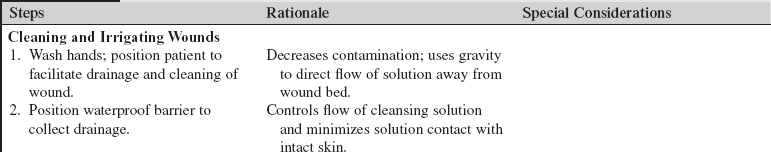

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

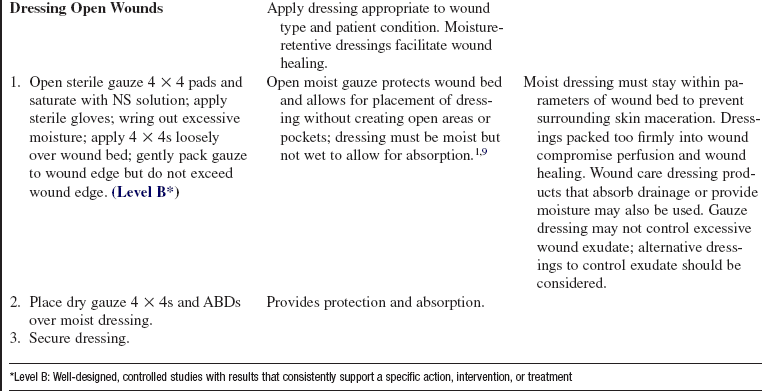

• Goals of wound care must be clearly outlined so that proper wound care products are used.

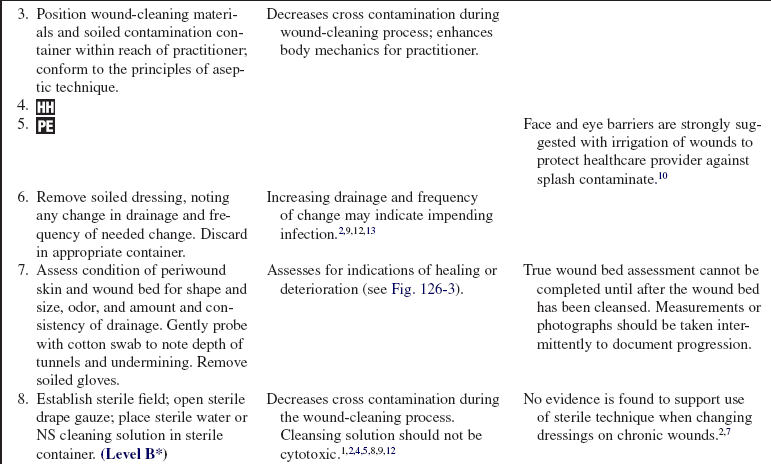

• Wound care products should be matched to the patient and wound conditions. Although no specific dressing is considered superior to others,9,13 properties of dressing products are different and should be assessed relative to wound treatment goals.2,9

Dressings may be categorized as semiocclusive or occlusive. Semiocclusive dressings are semipermeable to gases (O2, CO2, moisture) and are impermeable to liquids; they provide the moist wound healing environment that optimizes wound healing. Occlusive dressings lack permeability to gases and liquids.

Dressings may be categorized as semiocclusive or occlusive. Semiocclusive dressings are semipermeable to gases (O2, CO2, moisture) and are impermeable to liquids; they provide the moist wound healing environment that optimizes wound healing. Occlusive dressings lack permeability to gases and liquids.

Coarse gauze, used in a wet-to-dry dressing, nonselectively débrides the wound bed mechanically and absorbs wound fluid.

Coarse gauze, used in a wet-to-dry dressing, nonselectively débrides the wound bed mechanically and absorbs wound fluid.

Dressings such as calcium alginates, foams, and hydrofibers enhance wound exudate absorption; hydrogels, hydrocolloids, and transparent films provide moisture to nondraining wounds with minimal absorption.

Dressings such as calcium alginates, foams, and hydrofibers enhance wound exudate absorption; hydrogels, hydrocolloids, and transparent films provide moisture to nondraining wounds with minimal absorption.

Wounds with excessive wound drainage also require protection of periwound skin (i.e., skin barrier wipes).

Wounds with excessive wound drainage also require protection of periwound skin (i.e., skin barrier wipes).

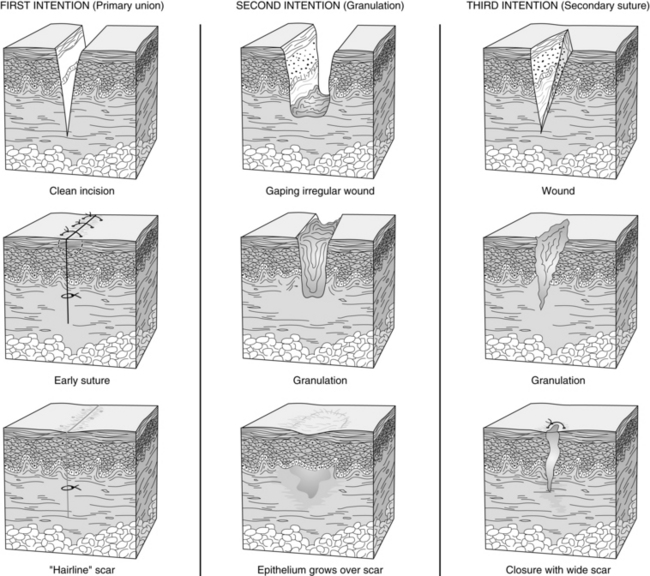

• Wounds heal by primary, secondary, or tertiary intention (Fig. 126-1).

Normal wound healing is often described as a progressive process that involves three overlapping phases: inflammation, proliferation, and maturation. The inflammatory phase is marked for hemostasis, increased vasodilation, and migration of neutrophils and macrophages to the area. The proliferation phase begins 2 to 4 days after injury and is the healing phase of the wound process in which epithelialization, angiogenesis, and collagen synthesis predominate.8,9 The maturation phase involves the body remodeling collagen fiber and increasing tissue tensile strength.8,9

Normal wound healing is often described as a progressive process that involves three overlapping phases: inflammation, proliferation, and maturation. The inflammatory phase is marked for hemostasis, increased vasodilation, and migration of neutrophils and macrophages to the area. The proliferation phase begins 2 to 4 days after injury and is the healing phase of the wound process in which epithelialization, angiogenesis, and collagen synthesis predominate.8,9 The maturation phase involves the body remodeling collagen fiber and increasing tissue tensile strength.8,9

Most clean wounds heal by primary intention. Suturing each layer of tissue approximates the wound edges. These wounds typically heal quickly and require minimal wound care.

Most clean wounds heal by primary intention. Suturing each layer of tissue approximates the wound edges. These wounds typically heal quickly and require minimal wound care.

Open wounds heal by secondary intention by granulating from the base of the wound to the skin surfaces and contracting and epithelializing from the wound edges; care must be taken to allow for uniform granulation and prevention of open pockets or tunneling.

Open wounds heal by secondary intention by granulating from the base of the wound to the skin surfaces and contracting and epithelializing from the wound edges; care must be taken to allow for uniform granulation and prevention of open pockets or tunneling.

Tertiary intention involves a period of secondary healing to achieve edema reduction and decreased exudate production, followed by surgical closure for primary healing.

Tertiary intention involves a period of secondary healing to achieve edema reduction and decreased exudate production, followed by surgical closure for primary healing.

• Clean, moist wound beds allow for effective wound healing under the support of a dressing.

Openly granulating wounds heal more slowly, may result in drying of granulating tissue and tissue death, and may be more painful for the patient.

Openly granulating wounds heal more slowly, may result in drying of granulating tissue and tissue death, and may be more painful for the patient.

The presence of exudate is not synonymous with infection but is the natural result of the inflammatory response to maintain moisture and allow movement and replication of epithelial cells necessary for healing. A change in volume, color, or consistency of exudate may indicate impending infection.2,4,12

The presence of exudate is not synonymous with infection but is the natural result of the inflammatory response to maintain moisture and allow movement and replication of epithelial cells necessary for healing. A change in volume, color, or consistency of exudate may indicate impending infection.2,4,12

• Wound cleansing should be accomplished with minimal chemical or mechanical trauma.

Cytotoxic cleaning agents (i.e., chlorhexidine, iodine, hydrogen peroxide) should be limited because they can delay healing.1,4,9,12

Cytotoxic cleaning agents (i.e., chlorhexidine, iodine, hydrogen peroxide) should be limited because they can delay healing.1,4,9,12

Wound cleaning solutions should be pH neutral.

Wound cleaning solutions should be pH neutral.

Normal saline (NS) solution is the cleaning agent of choice; however, tap water is safe and effective for cleaning of most acute and chronic wounds.1,5,14

Normal saline (NS) solution is the cleaning agent of choice; however, tap water is safe and effective for cleaning of most acute and chronic wounds.1,5,14

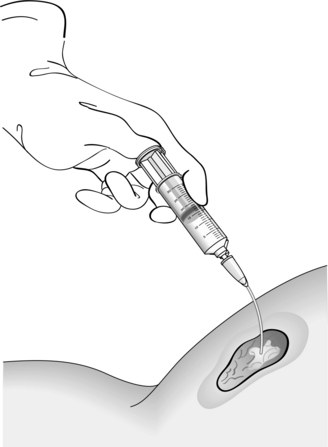

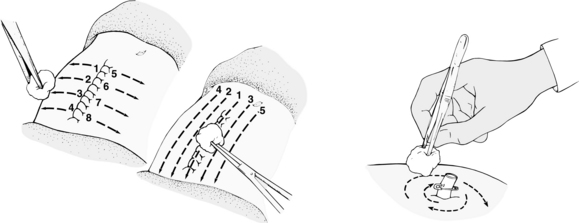

The cleaning solution must be delivered with enough force to physically loosen foreign materials and bacteria without injuring the tissue. Effective wound cleaning is best achieved when solution is delivered at 8 to 13 psi (Fig. 126-2). A 35-mL syringe attached to an 18-gauge angiocatheter tip only delivers fluid at 8 psi. A 12-mL syringe with a 22-gauge angiocatheter tip provides 13 psi. (Increasing syringe size decreases the pressure of the stream, and increasing the bore of the catheter tip increases the pressure.) Pressures greater than 15 psi may actually force bacteria and debris deeper into the wound bed.2,8,9,12

The cleaning solution must be delivered with enough force to physically loosen foreign materials and bacteria without injuring the tissue. Effective wound cleaning is best achieved when solution is delivered at 8 to 13 psi (Fig. 126-2). A 35-mL syringe attached to an 18-gauge angiocatheter tip only delivers fluid at 8 psi. A 12-mL syringe with a 22-gauge angiocatheter tip provides 13 psi. (Increasing syringe size decreases the pressure of the stream, and increasing the bore of the catheter tip increases the pressure.) Pressures greater than 15 psi may actually force bacteria and debris deeper into the wound bed.2,8,9,12

Figure 126-2 Irrigation of a wound.

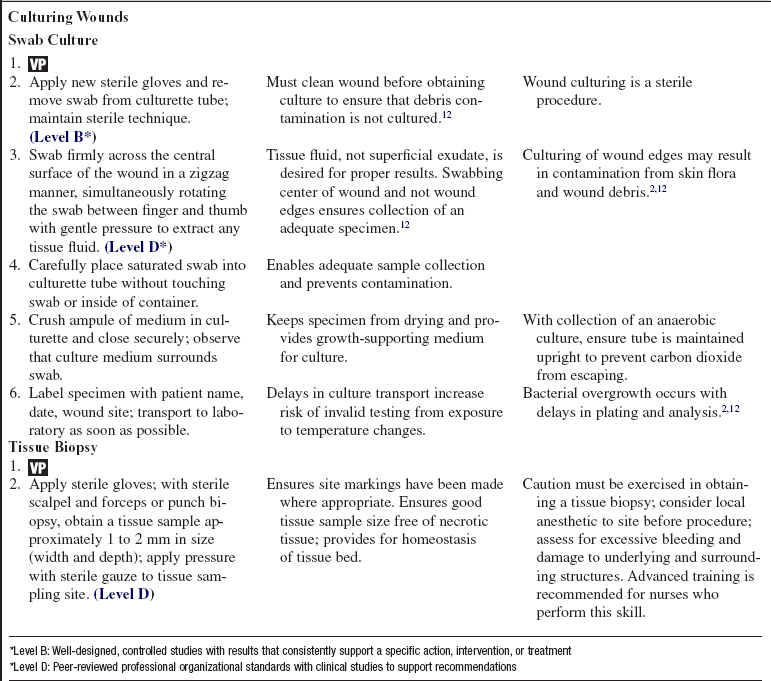

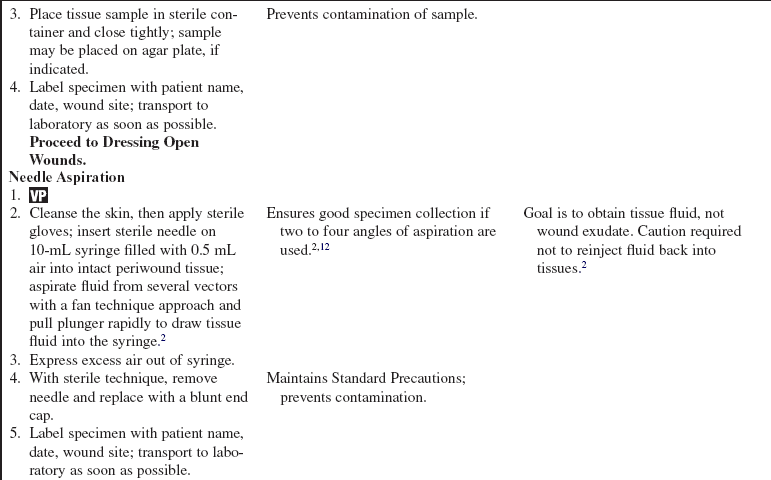

• Wound infections delay wound healing. Wound cultures (obtained before antibiotic therapy) may isolate organisms and differentiate between colonization and active infection.

Wound contamination is the presence of bacteria on the wound surface that are not actively multiplying. Signs and symptoms of infection are not present, and healing is not impaired.4,12

Wound contamination is the presence of bacteria on the wound surface that are not actively multiplying. Signs and symptoms of infection are not present, and healing is not impaired.4,12

Colonization is the presence of bacteria in the wound that are actively multiplying or forming colonies. Colonization can delay healing but may not elicit signs of infection.

Colonization is the presence of bacteria in the wound that are actively multiplying or forming colonies. Colonization can delay healing but may not elicit signs of infection.

Wound infection is present if organisms are present at 105 colony-forming units per milliliter (103 for virulent organisms like β-hemolytic strep4) in conjunction with clinical findings such as erythema, edema, pain, purulence, fever, and leukocytosis.

Wound infection is present if organisms are present at 105 colony-forming units per milliliter (103 for virulent organisms like β-hemolytic strep4) in conjunction with clinical findings such as erythema, edema, pain, purulence, fever, and leukocytosis.

With the proliferation of organisms like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and aggressive bacteria that cause necrotizing soft tissue infections (e.g., group A Streptococci and Streptococcus pyogenes), the standard of empirically implementing antibiotic treatment without wound culture is being questioned. Knowledge of whether resistant strains of bacteria are present at the onset of treatment is critical to provide the optimal situation for healing and rapid intervention.4,11

With the proliferation of organisms like methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA) and aggressive bacteria that cause necrotizing soft tissue infections (e.g., group A Streptococci and Streptococcus pyogenes), the standard of empirically implementing antibiotic treatment without wound culture is being questioned. Knowledge of whether resistant strains of bacteria are present at the onset of treatment is critical to provide the optimal situation for healing and rapid intervention.4,11

Bacterial invasion of wounds is managed with cleansing, débridement (see Procedure 127), and antibiotic therapy (local or systemic). Soaking can macerate wound and periwound tissues and may not improve bacterial counts.14

Bacterial invasion of wounds is managed with cleansing, débridement (see Procedure 127), and antibiotic therapy (local or systemic). Soaking can macerate wound and periwound tissues and may not improve bacterial counts.14

CRITICAL CARE DIMENSION

Critically ill patients commonly encounter factors that impair adequate wound healing, compounding the risks for poor patient outcomes. Nursing care should focus on early recognition and correction of underlying systemic disorders and patient-specific comorbidities that can impede wound healing goals.2,8,9,12,13

• Frequent comorbidities that can compromise optimal healing trajectories are diabetes mellitus, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, peripheral vascular disease, cancer, endocrine imbalances, renal failure, cerebral vascular accident, nicotine addiction, alcohol abuse, neurovascular deficit, obesity, and ascites.

• Trauma-associated wound considerations include penetrating injuries that create anaerobic pockets and deep tissue injury; reperfusion of previously ischemic injuries that can trigger paradoxic injury extension; and possible contamination with organic and inorganic bodies that can inhibit effective wound healing, including feces, saliva, soils, and environmental vectors such as metal, rock, and glass.

• Sometimes medications and treatment interventions may jeopardize wound healing goals. Medications that impair tissue perfusion (i.e., vasoconstrictors) or the immune response (i.e., steroids, immunomodulators, antirejection drugs, antineoplastics) and treatments that impair tissue hydration (diuretics and fluid restrictions) may adversely affect wound healing.

• Poor nutritional status includes low serum protein, vitamin C, zinc, copper, and magnesium.

• Altered blood chemistries, especially hypokalemia and hyperglycemia (>200 mg/dL) and acid-base disturbances, should be assessed.

• Other factors that compound effective wound healing include hypothermia or hyperthermia, extended surgical procedures, intraoperative hypotension, immobility, hypoxemia, anemia, poor tissue oxygenation, sepsis, extremes of age, inadequate sleep or rest, uncontrolled pain, clotting abnormalities, mechanical friction on the wound, and the development of adhesions or hypertrophic or keloid scars.

EQUIPMENT

• Nonsterile and sterile gloves (two pairs); sterile field (depending on type and age of wound)

• Personal protective equipment (as needed)

• Two or three sterile cotton-tipped applicators for use in measurement

• (NS) solution or ordered irrigation solution

• Sterile 35-mL slip-tip syringe and 18-gauge angiocatheter sheath for irrigation (if necessary)

• Sterile gauze (4 × 4); possibly, ABD dressings (if the wound has excessive drainage, an absorptive dressing may be necessary; if the wound has minimal drainage, a moisture-enhancing dressing may be needed)

• Liquid skin barrier or wafer; apply around the wound edge to protect periwound tissue

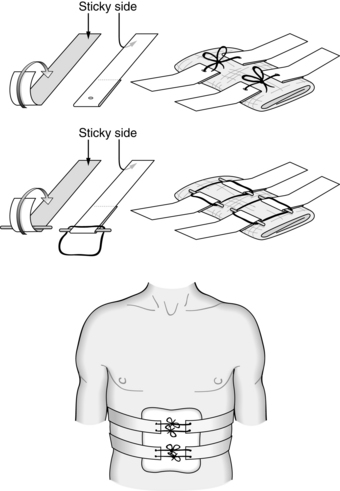

• Hypoallergenic tape; tubular mesh bandage or one set of Montgomery straps

Additional equipment to have available, if needed, includes the following:

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and rationale that supports wound cleaning and dressing management.  Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased.

Rationale: Patient anxiety and discomfort are decreased.

• Discuss patient’s role in the procedure.  Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited; patient is prepared for wound management on discharge (as appropriate).

Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited; patient is prepared for wound management on discharge (as appropriate).

• Explain the reason for obtaining a wound culture.  Rationale: Patient anxiety is decreased.

Rationale: Patient anxiety is decreased.

• Discuss signs and symptoms of local and systemic wound infection (erythema, pain, increased wound drainage, odor, fever) and inform when patient should consult a healthcare provider.  Rationale: The patient is prepared for wound management on discharge.

Rationale: The patient is prepared for wound management on discharge.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

Wound drainage (amount, consistency, color, and possible odor)

Wound drainage (amount, consistency, color, and possible odor)

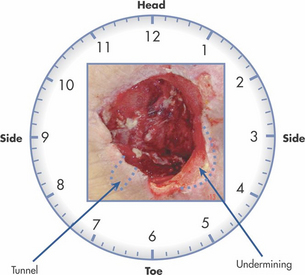

Size, shape, length, width, and depth of wound bed, including pockets (Fig. 126-3)

Size, shape, length, width, and depth of wound bed, including pockets (Fig. 126-3)

Appearance of wound bed (color, presence of debris; i.e., necrotic or darkened areas on tissue bed are black; slough is green or cream yellow; and healthy tissue is red)

Appearance of wound bed (color, presence of debris; i.e., necrotic or darkened areas on tissue bed are black; slough is green or cream yellow; and healthy tissue is red)

Condition of wound margins and periwound skin (intact versus maceration or xerosis; abnormal textures/undermining)

Condition of wound margins and periwound skin (intact versus maceration or xerosis; abnormal textures/undermining)

Presence of erythema (blanches with pressure) or ecchymosis (does not blanch with pressure)

Presence of erythema (blanches with pressure) or ecchymosis (does not blanch with pressure)

Elevated temperature or localized warmth at wound site

Elevated temperature or localized warmth at wound site

White blood cell count; may be elevated or show a change from baseline

White blood cell count; may be elevated or show a change from baseline

With advance age, subtle changes in activity and cognition may be the only indications of infection2,6

With advance age, subtle changes in activity and cognition may be the only indications of infection2,6

Rationale: Assessment provides information about the healing process and assists in early identification of wound infection. True wound bed assessment cannot be completed until after the wound bed has been cleansed.

Rationale: Assessment provides information about the healing process and assists in early identification of wound infection. True wound bed assessment cannot be completed until after the wound bed has been cleansed.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Place patient in position of optimal comfort and visualization for wound care procedures.  Rationale: Proper positioning provides for effective wound visualization and enhances patient tolerance of procedure.

Rationale: Proper positioning provides for effective wound visualization and enhances patient tolerance of procedure.

• Optimize lighting in room and provide privacy for patient.  Rationale: Lighting allows for optimal wound assessment, and privacy provides patient comfort.

Rationale: Lighting allows for optimal wound assessment, and privacy provides patient comfort.

• Administer premedication with prescribed analgesic, if indicated.  Rationale: Medication decreases patient anxiety and increases comfort. Pain and stress are recognized deterrents for healing.3,13

Rationale: Medication decreases patient anxiety and increases comfort. Pain and stress are recognized deterrents for healing.3,13

Figure 126-4 Cleaning of a wound. (From Potter PA, Perry A: Basic nursing: essentials for practice, ed 5, St Louis, 2003, Mosby.)

Figure 126-5 Montgomery straps.

References

![]() 1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Clinical practice guideline. treatment of pressure ulcers,. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, 1994.

1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Clinical practice guideline. treatment of pressure ulcers,. US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, 1994.

2. Bates-Jensen BM, Ovington, LG. Management of exudate and infection. In: Sussman C, Bates-Jensen BM, eds. Wound care: a collaborative practice manual. ed 3. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer; 2007:215–233.

![]() 3. Broadbent, E, Petrie, K, Alley, PG, et al. Psychological stress impairs early wound repair following surgery. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65(5):865–869.

3. Broadbent, E, Petrie, K, Alley, PG, et al. Psychological stress impairs early wound repair following surgery. Psychosom Med. 2003; 65(5):865–869.

![]() 4. Edwards, R, Harding, KG. Bacteria and wound healing. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004; 17(2):91–96.

4. Edwards, R, Harding, KG. Bacteria and wound healing. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2004; 17(2):91–96.

5. Fernandez, R, Griffiths, R. Water for wound cleansing. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2008; 23(1):CD003861.

6. Johnson, CB, Harper, GM, Landsfeld, CS. Geriatric -medicine. In: McPhee SJ, Papadakis MA, Tierney LM, Jr., eds. Current medical diagnosis and treatment. ed 47. New York: Lange Medical Books/McGraw-Hill; 2008:51–66.

![]() 7. Lawson, C, Juliano, L, Ratilff, CR. Does sterile or nonsterile technique make a difference in wounds healing by -secondary intention. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2003; 49(4):56–60.

7. Lawson, C, Juliano, L, Ratilff, CR. Does sterile or nonsterile technique make a difference in wounds healing by -secondary intention. Ostomy Wound Manage. 2003; 49(4):56–60.

8. Makic, MB, McQuillan, KA. Wound healing and soft -tissue injuries. In: McQuillan KA, Makic MB, Whalen E, eds. Trauma nursing: from resuscitation through -rehabilitation. ed 4. St Louis: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:306–329.

9. Rolstad, BS, Ovington, LG. Principles of wound management. In: Byrant RA, Nix CP, eds. Acute and chronic wounds. ed 3. Philadelphia: Mosby Elsevier; 2007:-391–426.

10. Siegel, JD, Rhinehart, E, Jackson, M, et al, Healthcare Infection Control Practices Advisory Committee, guideline for isolation precautions. preventing transmission of infectious agents in healthcare settings; transmission-based precautions,. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, 2007.

11. Storr, A, Inappropriate therapy for methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. resource utilization and cost implications. Crit Care Med. 2008; 36(8):2335–2340.

12. Stotts, N, Wound infection. diagnosis and managementByrant RA, Nix CP, eds.. Acute and chronic wounds. ed 3. Mosby Elsevier, Philadelphia, 2007:161–175.

13. Sussman, C, Bates-Jensen, B, Wound healing physiology. acute and chronicSussman C, Bates-Jensen B, eds.. Wound care: a collaborative practice manual for health professionals. ed 3. Wolters Kluwer, Philadelphia, 2007:21–51.

14. The Joanna Briggs Institute, Solutions, techniques and pressure for wound cleansing. www.joannabriggs.edu.au retrieved September 10, 2008, from. Best Pract. 2006; 10(2):1–4.

Baranoski, S, Choosing a wound dressing. part I. Nursing. 2008; 38(1):60–616.

Baranoski, S, Choosing a wound dressing. part II. Nursing. 2008; 38(2):14–15.

Bates-Jensen, BM, MacLean. Quality indicators for the care of pressure ulcers in vulnerable elders. J Am Geriatr Soc. 2007; 55(Suppl 2):S409–S416.

Moore, Z, Cowan, S. A systematic review of wound cleansing for pressure ulcers. J Clin Nurs. 2008; 17(15):1963–1972.

Wound Ostomy and Continence Nurses (WOCN) Society. Guideline for prevention and management of pressure ulcers (series),. Glenview, IL: WOCN; 2003.