Wound Closure

Wound Closure

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• The skin is the largest organ of the body and has two major tissue layers. The outermost layer, the epidermis, is made of stratified, squamous cells with keratin and melanin. This layer protects against environmental exposure, restricts water loss, and gives color. The inner layer, the dermis, is made of fibroelastic connective tissue with capillaries, lymphatics, and nerve endings and provides nourishment and strength. The layer beneath the dermis is the subcutaneous tissue, composed of areolar and fatty connective tissue to provide insulation, shock absorption, and calorie reserve.

• The natural components of wound healing include three overlapping phases of healing: inflammation, proliferation, and maturation.

Inflammation: Wound extends through the epidermis, disrupts blood vessels, and exposes collagen, activating the clotting cascade and inflammatory response. Vascular and cellular responses are designed to protect the body against foreign substances and limit blood loss via vasoconstriction and development of a clot providing hemostasis. The inflammatory response activates macrophages and clears the wound of cellular debris. Hemostasis with fibrin formation creates a protective wound scab. Kinins and prostaglandins produce local vasodilation and increase permeability of the vasculature, thereby promoting development of inflammatory exudate. Inflammation brings chemical stimuli for wound repair. Wounds left open for 3 hours show a dramatic increase in vascular permeability, which results in thick inflammatory exudate and may limit the therapeutic value of antibiotics.5,21

Inflammation: Wound extends through the epidermis, disrupts blood vessels, and exposes collagen, activating the clotting cascade and inflammatory response. Vascular and cellular responses are designed to protect the body against foreign substances and limit blood loss via vasoconstriction and development of a clot providing hemostasis. The inflammatory response activates macrophages and clears the wound of cellular debris. Hemostasis with fibrin formation creates a protective wound scab. Kinins and prostaglandins produce local vasodilation and increase permeability of the vasculature, thereby promoting development of inflammatory exudate. Inflammation brings chemical stimuli for wound repair. Wounds left open for 3 hours show a dramatic increase in vascular permeability, which results in thick inflammatory exudate and may limit the therapeutic value of antibiotics.5,21

Proliferation and epithelialization: This phase of wound healing is characterized by generation of new tissue, angiogenesis, and collagen formation. After an incision, the divided parts of the epithelium are closed by cellular migration and mitosis, forming an epithelial bridge that protects the wound against bacteria. When the skin edges are slightly everted with suturing, epithelial bridging occurs within 18 to 24 hours. Wounds that have approximated skin edges may take 36 hours to epithelialize. If the edges are inverted, it may take up to 72 hours to completely epithelialize.5

Proliferation and epithelialization: This phase of wound healing is characterized by generation of new tissue, angiogenesis, and collagen formation. After an incision, the divided parts of the epithelium are closed by cellular migration and mitosis, forming an epithelial bridge that protects the wound against bacteria. When the skin edges are slightly everted with suturing, epithelial bridging occurs within 18 to 24 hours. Wounds that have approximated skin edges may take 36 hours to epithelialize. If the edges are inverted, it may take up to 72 hours to completely epithelialize.5

Maturation is the remodeling phase of wound tissues during which collagen is reorganized to increase strength of the new tissue.

Maturation is the remodeling phase of wound tissues during which collagen is reorganized to increase strength of the new tissue.

• Wound healing occurs via primary or secondary intention.

• Primary intention is used with limited tissue loss; the wound is clean, and the wound edges can be approximated and closed, frequently with sutures or staples.

• Secondary intention is used when either a large amount of tissue has been lost or the wound is contaminated.21 Wound dressing techniques are used to clean the wound and encourage development of granulation tissue and reepithelialization for wound closure.

• The goals of primary wound closure are to stop bleeding, prevent infection, preserve function, and restore appearance.

• Principles of proper wound closure include the following:

Elimination of dead space where serum and blood can accumulate, thus decreasing the risk for infection

Elimination of dead space where serum and blood can accumulate, thus decreasing the risk for infection

Accurate approximation of deep tissue layers to each other with minimal tension on the surrounding tissues

Accurate approximation of deep tissue layers to each other with minimal tension on the surrounding tissues

Avoidance of tissue ischemia and strangulation from tying sutures too tightly

Avoidance of tissue ischemia and strangulation from tying sutures too tightly

Decreased risk for infection by closing clean wounds within 3 to 8 hours of injury and using aseptic technique in all aspects of wound management

Decreased risk for infection by closing clean wounds within 3 to 8 hours of injury and using aseptic technique in all aspects of wound management

• Risk factors for surgical site infections include intrinsic factors (such as age, active skin condition, smoking status, body mass index, and comorbidities) and extrinsic factors (e.g., preoperative, perioperative, and postoperative patient care practices, such as preoperative skin preparation and postoperative dressings).14 Risk factors for infection in a traumatic laceration include extremes of age, history of diabetes mellitus, chronic renal failure, jagged wound edges, stellate shape, visible contamination, injury deeper than the subcutaneous tissue, and presence of a foreign body.10,15,18

• Hair removal around suture site is not necessary before suturing unless the hair interferes with the procedure. Removal of hair has been associated with higher risk of infection. If hair must be removed, an electric clipper is preferred. A razor can cause abrasions and microscopic skin nicks that may increase the risk of infection.6,14,16,19

• Depending on the clinical setting, referral to an appropriate specialist (e.g., vascular, orthopedic, plastic, or general surgeon) may be warranted for wounds with damage to the blood supply, nerves, or joint; wounds on the face; or wounds with extensive tissue damage or infection.

• Wounds contaminated or infected with saliva, feces, or purulent exudate or that have been open longer than 8 hours may benefit from delayed closure on or after the fourth day to decrease the risk for infection.

• Wounds may be closed with several techniques: sutures, staples, adhesive skin strips (i.e., Steri-Strips, or skin adhesives.

Staples provide the strongest closure, skin adhesives and sutures are next strongest, and adhesive skin strips are the weakest.1

Staples provide the strongest closure, skin adhesives and sutures are next strongest, and adhesive skin strips are the weakest.1

Stapling is faster, less expensive, and more cosmetically acceptable than suturing in the repair of many types of traumatic lacerations. Staples are useful for lacerations to the scalp, trunk, and extremities. They are slightly more painful to remove.

Stapling is faster, less expensive, and more cosmetically acceptable than suturing in the repair of many types of traumatic lacerations. Staples are useful for lacerations to the scalp, trunk, and extremities. They are slightly more painful to remove.

Adhesive skin strips (i.e., Steri-Strips) and skin adhesives are found to be equal in cosmetic outcomes and acceptability.12,15 They are best used on wounds that are not under tension.

Adhesive skin strips (i.e., Steri-Strips) and skin adhesives are found to be equal in cosmetic outcomes and acceptability.12,15 They are best used on wounds that are not under tension.

Skin adhesives such as 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond, Ethicon, Inc.) have been shown to be equivalent to sutures in repair of simple, clean wounds on children. Adhesives should not be used over joints; on hands, feet, lips, or mucosa; on infected, puncture, or stellate wounds; or in patients with poor circulation or a propensity to form keloids.6 They are best suited for short (less than 6 to 8 cm), low-tension, clean-edged, straight to curvilinear wounds that do not cross joints or creases.2,7,8

Skin adhesives such as 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond, Ethicon, Inc.) have been shown to be equivalent to sutures in repair of simple, clean wounds on children. Adhesives should not be used over joints; on hands, feet, lips, or mucosa; on infected, puncture, or stellate wounds; or in patients with poor circulation or a propensity to form keloids.6 They are best suited for short (less than 6 to 8 cm), low-tension, clean-edged, straight to curvilinear wounds that do not cross joints or creases.2,7,8

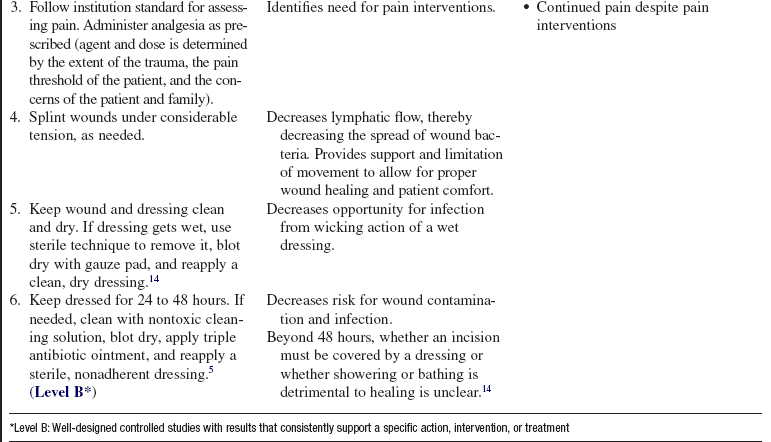

Curved needles are either tapered or cutting. Needles used for skin closure have an angle of 135 degrees.

Curved needles are either tapered or cutting. Needles used for skin closure have an angle of 135 degrees.

Tapered needles are used in soft tissues (intestine, blood vessels, muscle, and fascia) and produce minimal tissue damage.

Tapered needles are used in soft tissues (intestine, blood vessels, muscle, and fascia) and produce minimal tissue damage.

Cutting needles are used to approximate tougher tissue, such as skin. Reverse cutting needles have a cutting edge on the outside of the curve and provide a wall of tissue, rather than an incision, for the suture to rest against. This method resists suture cut-through and is therefore preferred.

Cutting needles are used to approximate tougher tissue, such as skin. Reverse cutting needles have a cutting edge on the outside of the curve and provide a wall of tissue, rather than an incision, for the suture to rest against. This method resists suture cut-through and is therefore preferred.

Most needles are swaged, or molded, around the suture, providing convenience, safety, and speed in suture placement.

Most needles are swaged, or molded, around the suture, providing convenience, safety, and speed in suture placement.

Needles should be handled only with needle holders to prevent needle damage to surrounding tissue and injury to the user.

Needles should be handled only with needle holders to prevent needle damage to surrounding tissue and injury to the user.

Suture material is characterized by tissue reactivity, flexibility, knot-holding ability, wick action, and tensile strength. Suture size is indicated by “0.” The higher the number that precedes “0,” the smaller the suture (e.g., 4-0 is smaller than 3-0).

Suture material is characterized by tissue reactivity, flexibility, knot-holding ability, wick action, and tensile strength. Suture size is indicated by “0.” The higher the number that precedes “0,” the smaller the suture (e.g., 4-0 is smaller than 3-0).

Sutures are absorbable or nonabsorbable, braided, or monofilament.

Sutures are absorbable or nonabsorbable, braided, or monofilament.

Absorbable suture (i.e., natural gut, synthetic polymers) is used for layered closures. Gut suture is broken down via phagocytosis and induces a moderate inflammatory reaction. Chromic gut suture has increased strength and lasts longer in tissue, but it is not used on the skin because it can cause a severe tissue reaction. Synthetic absorbable sutures are favored over gut because of decreased infection rates and increased strength and longevity.3

Absorbable suture (i.e., natural gut, synthetic polymers) is used for layered closures. Gut suture is broken down via phagocytosis and induces a moderate inflammatory reaction. Chromic gut suture has increased strength and lasts longer in tissue, but it is not used on the skin because it can cause a severe tissue reaction. Synthetic absorbable sutures are favored over gut because of decreased infection rates and increased strength and longevity.3

Nonabsorbable sutures are either natural fibers (i.e., silk, cotton, linen) or synthetic (i.e., nylon, Dacron, polyethylene) and are best for superficial lacerations because they are supple and easily handled and facilitate knot construction.

Nonabsorbable sutures are either natural fibers (i.e., silk, cotton, linen) or synthetic (i.e., nylon, Dacron, polyethylene) and are best for superficial lacerations because they are supple and easily handled and facilitate knot construction.

Braided sutures are stronger, but the small spaces between the braids may harbor infection.

Braided sutures are stronger, but the small spaces between the braids may harbor infection.

Monofilament is best suited for skin closure because it produces less inflammatory response; however, the knots are less dependable.

Monofilament is best suited for skin closure because it produces less inflammatory response; however, the knots are less dependable.

Nonabsorbable synthetic monofilament sutures (i.e., 4-0 or 5-0 nylon) are preferred for skin closure. Synthetic braided absorbable sutures provide the best closure for interrupted dermal sutures and ligation of bleeding vessels.

Nonabsorbable synthetic monofilament sutures (i.e., 4-0 or 5-0 nylon) are preferred for skin closure. Synthetic braided absorbable sutures provide the best closure for interrupted dermal sutures and ligation of bleeding vessels.

Preferred knotting technique involves a square knot or double loop followed by a square knot tie.

Preferred knotting technique involves a square knot or double loop followed by a square knot tie.

Injured tissue becomes edematous, and the suture tightens automatically within 12 to 24 hours; therefore, the practitioner must avoid tying the suture too tightly, which could produce tissue necrosis.

Injured tissue becomes edematous, and the suture tightens automatically within 12 to 24 hours; therefore, the practitioner must avoid tying the suture too tightly, which could produce tissue necrosis.

The number of sutures required is the minimum needed to hold the wound edges exactly opposed without crimping. Tension should be minimized but not eliminated on the wound edges. The more tension on a wound, the closer the sutures should be placed.

The number of sutures required is the minimum needed to hold the wound edges exactly opposed without crimping. Tension should be minimized but not eliminated on the wound edges. The more tension on a wound, the closer the sutures should be placed.

Lacerations are approximated with a variety of suturing techniques5:

Lacerations are approximated with a variety of suturing techniques5:

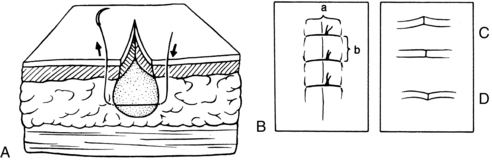

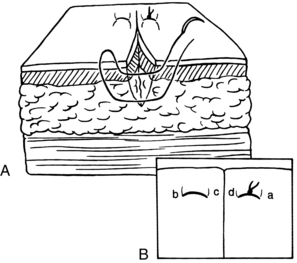

Simple interrupted dermal suture (Fig. 124-1) is used when the skin margins are level or slightly everted. The needle should enter and exit the skin surface at a right angle. The stitch should be as wide as the suture is deep and no closer than 2 mm apart. The knot should be tied with an instrument tie and repeated four or five times. The first suture is placed in the midportion of the wound. Additional sutures are placed in bisected portions of the wound until it is appropriately closed.

Simple interrupted dermal suture (Fig. 124-1) is used when the skin margins are level or slightly everted. The needle should enter and exit the skin surface at a right angle. The stitch should be as wide as the suture is deep and no closer than 2 mm apart. The knot should be tied with an instrument tie and repeated four or five times. The first suture is placed in the midportion of the wound. Additional sutures are placed in bisected portions of the wound until it is appropriately closed.

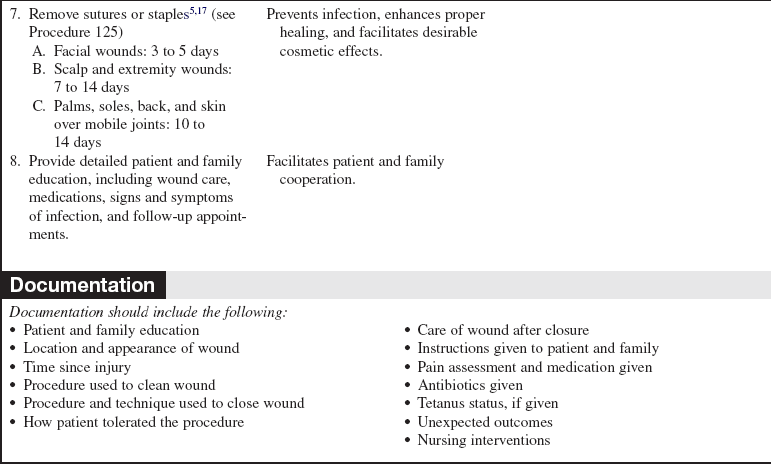

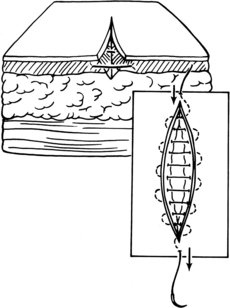

• Subcutaneous suture with inverted knot or buried stitch (Fig. 124-2) is used for deeper wounds or wounds under tension. Absorbable sutures are used with the knot inverted below the skin margin. Begin at the bottom of the wound, come up and go straight across the incision to the base again, and tie. Deep, buried subcutaneous sutures are used to reduce the tension on skin sutures, close dead space beneath a wound, and allow for early suture removal.9,13

Figure 124-2. Inverted subcutaneous suture. Also shown is layered closure. (From Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s procedures for primary care, ed 2, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

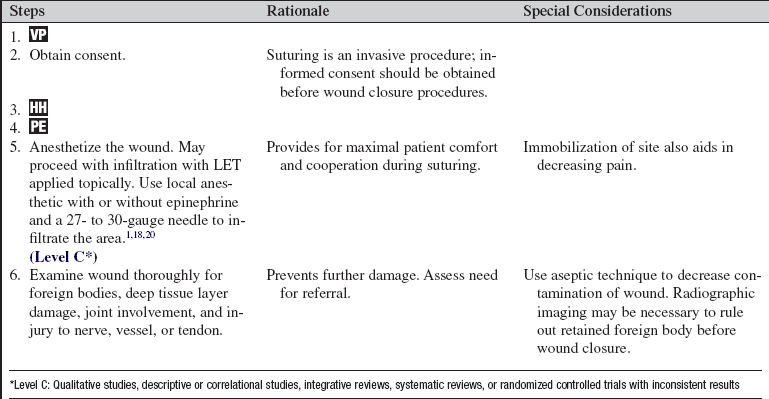

• Vertical mattress suture (Fig. 124-3) promotes eversion of the skin, which promotes less prominent scarring.13 Mattress sutures are used when skin tension is present or where the skin is very thick (palms and soles of feet). This suture is identical to a simple suture, but an additional suture is taken very close to the edge of each side of the wound.

Figure 124-3 Vertical mattress suture. A, Cross section. B, Overhead view. Begin at a, and go under skin to b. Come out, go in at c, and exit at d. (From Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s procedures for primary care, ed 2, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

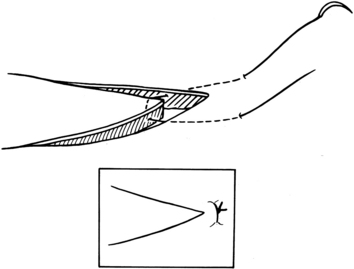

• Three-point or half-buried mattress suture (Fig. 124-4) is used to close an acute corner of a laceration without impairing blood flow to the tip. The needle is inserted into the skin on the nonflap portion of the wound, passed transversely through the tip, and returned on the opposite side of the wound, paralleling the point of entrance. The suture is then tied, drawing the tip snugly in place.9,13

Figure 124-4 Three-point or half-buried mattress. (From Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s procedures for primary care, ed 2, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

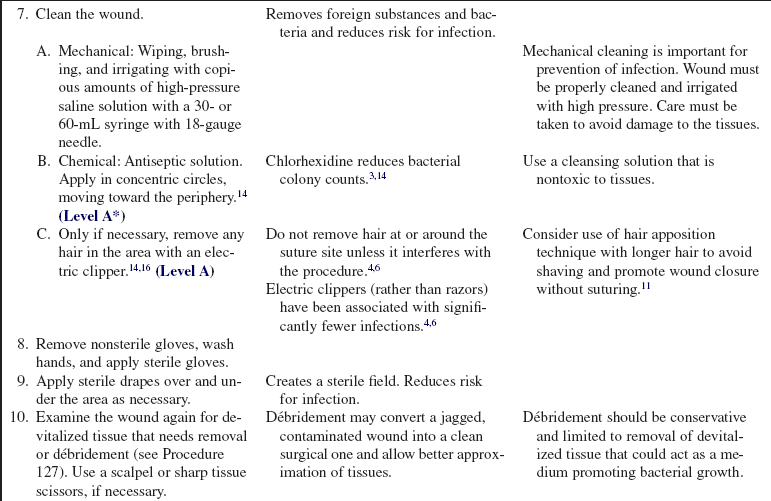

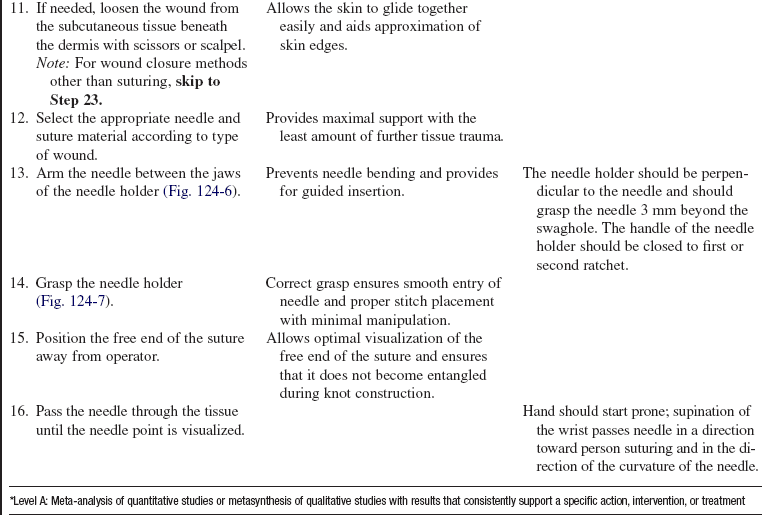

• Subcuticular running suture (Fig. 124-5) is used for linear wounds under little or no tension and allows for edema formation. Wound approximation may not be as meticulous as with an interrupted dermal suture. An anchor suture is placed at one end of the wound, then continuous sutures are placed at right angles to the wound less than 3 mm apart. The wound is pulled together and the other end secured with either another square knot or tape under slight tension.

Figure 124-5 Subcuticular running suture. (From Pfenninger JL, Fowler GC, editors: Pfenninger and Fowler’s procedures for primary care, ed 2, St Louis, 2006, Mosby.)

Sutures must be completely removed in a timely fashion to avoid further tissue inflammation and possible infection. Sutures on extremities and the trunk should be removed in 8 to 14 days; those on the face should be removed in 3 to 5 days; and those on the palms, soles, back, and skin over mobile joints should be removed in 10 to 14 days.5,17

Sutures must be completely removed in a timely fashion to avoid further tissue inflammation and possible infection. Sutures on extremities and the trunk should be removed in 8 to 14 days; those on the face should be removed in 3 to 5 days; and those on the palms, soles, back, and skin over mobile joints should be removed in 10 to 14 days.5,17

EQUIPMENT

• Local anesthetic (with or without epinephrine)

• Chlorhexidine solution3 and sterile normal saline (NS) solution

• 30- or 60-mL syringe and 18-gauge needle

• Sterile gloves, mask, eye protection

• Electric clippers (only if hair removal necessary)

• Note: Some hospitals use prepackaged suture kits; thus, it may be unnecessary to assemble all of the items listed here if such a kit is available.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and risks and reassure the patient and family.  Rationale: Explanation decreases patient anxiety and encourages patient and family cooperation and understanding of procedure.

Rationale: Explanation decreases patient anxiety and encourages patient and family cooperation and understanding of procedure.

• As appropriate, instruct the patient and family on aftercare: pain medication, wound care, observation for signs and symptoms of infection, and when to have wound closure material removed.  Rationale: Instruction facilitates patient comfort, decreases risk for infection, and encourages prompt intervention to treat possible infection.

Rationale: Instruction facilitates patient comfort, decreases risk for infection, and encourages prompt intervention to treat possible infection.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Obtain history of present injury and medical history.  Rationale: This knowledge allows a better understanding of the nature of the injury and any complicating factors to wound healing.

Rationale: This knowledge allows a better understanding of the nature of the injury and any complicating factors to wound healing.

• Assess damage to peripheral nerve, blood supply, or motor function; radiographs may be needed to assess for bone injury.  Rationale: Assessment determines the need for referral to a specialist.

Rationale: Assessment determines the need for referral to a specialist.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that patient understands preprocedural teachings and obtain consent. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Suturing is an invasive procedure, so consent should be obtained before the procedure is started. Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Suturing is an invasive procedure, so consent should be obtained before the procedure is started. Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Administer pain medication as necessary. Consider moderate procedural sedation for laceration repair in children.15 Consider use of LET (lidocaine, 4%; epinephrine, 0.1%; and tetracaine, 0.5%) topically for children.  Rationale: Pain medication reduces activity significantly during suturing to provide a stable field.

Rationale: Pain medication reduces activity significantly during suturing to provide a stable field.

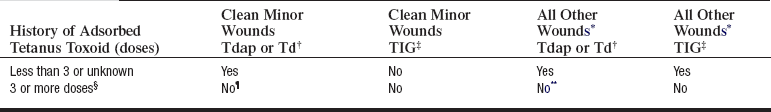

• Administer tetanus prophylaxis, if necessary (Table 124-1).  Rationale: Possibility of tetanus from unclean wound is prevented.

Rationale: Possibility of tetanus from unclean wound is prevented.

Table 124-1

Guide to Tetanus Prophylaxis in Wound Management

*Such as (but not limited to) wounds contaminated with dirt, feces, soil, and saliva; puncture wounds; avulsions; and wounds resulting from missiles, crushing, burns, and frostbite.

†For children younger than 7 years of age, DTaP is recommended; if pertussis vaccine is contraindicated, DT is given. For persons 7 to 9 years of age or 65 years or older, Td is recommended. For persons 10 to 64 years, Tdap is preferred to Td if the patient has never received Tdap and has no contraindication to pertussis vaccine. For persons 7 years of age or older, if Tdap is not available or not indicated because of age, Td is preferred to TT.

‡TIG, Human tetanus immune globulin. Equine tetanus antitoxin should be used when TIG is not available.

§If only three doses of fluid toxoid have been received, a fourth dose of toxoid, preferably an adsorbed toxoid, should be given. Although licensed, fluid tetanus toxoid is rarely used.

¶Yes, if it has been 10 years or longer since the last dose.

**Yes, if it has been 5 years or longer since the last dose. More frequent boosters are not needed and can accentuate side effects.

(Manual for the surveillance of vaccine-preventable diseases, ed 4, 2008, available at www.cdc.gov/vaccines/pubs/surv-manual/chpt16-tetanus.htm#9.)

References

![]() 1. Autio, L, Olson, KK, The four S’s of wound management. staples, sutures, Steri-Strips, and sticky stuff. Holist Nurs Pract 2002; 16:80–88.

1. Autio, L, Olson, KK, The four S’s of wound management. staples, sutures, Steri-Strips, and sticky stuff. Holist Nurs Pract 2002; 16:80–88.

2. Beam, JW. Tissue adhesives for simple traumatic lacerations. J Athletic Training. 2008; 43(2):222–224.

![]() 3. Chaiyakunapruk, N, et al, Chlorhexidine compared with povidone-iodine solution for vascular catheter-site care. a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136:792–801.

3. Chaiyakunapruk, N, et al, Chlorhexidine compared with povidone-iodine solution for vascular catheter-site care. a meta-analysis. Ann Intern Med 2002; 136:792–801.

4. Cole, E. Wound closure using adhesive strips. Nurs Stand. 2007; 22(9):48–49.

![]() 5. Edlich, RF, Woods, JA, Drake, DB. Scientific basis of wound closure techniques. Norwalk, CT: Auto Suture Company; 1996.

5. Edlich, RF, Woods, JA, Drake, DB. Scientific basis of wound closure techniques. Norwalk, CT: Auto Suture Company; 1996.

![]() 6. Edlich, RF, et al. A scientific basis for choosing the technique of hair removal used prior to wound closure. J Emerg Nurs. 2000; 26:134–139.

6. Edlich, RF, et al. A scientific basis for choosing the technique of hair removal used prior to wound closure. J Emerg Nurs. 2000; 26:134–139.

![]() 7. Farion, KJ, et al, Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations. a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acad Emerg Med 2003; 10:110–118.

7. Farion, KJ, et al, Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations. a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acad Emerg Med 2003; 10:110–118.

![]() 8. Farion, KJ, Russell, KF, Osmond, MH, et al, Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 4:CD003326, doi: 10. 1002/14651858. [CD003326].

8. Farion, KJ, Russell, KF, Osmond, MH, et al, Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations in children and adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2004; 4:CD003326, doi: 10. 1002/14651858. [CD003326].

![]() 9. Hanasono, MM, Hotchkiss, RN. Locking horizontal mattress suture. Dermatol Surg. 2005; 31:572–573.

9. Hanasono, MM, Hotchkiss, RN. Locking horizontal mattress suture. Dermatol Surg. 2005; 31:572–573.

10. Henry, FP, Purcell, EM, Eadie, PA, The human bite injury. a clinical audit and discussion regarding the management of this alcohol fuelled phenomenon. Emerg Med J 2007; 23:455–458.

![]() 11. Hock, MO, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the hair apposition technique with tissue glue to standard suturing in scalp lacerations (HAT study). Ann Emerg Med. 2002; 40:19–26.

11. Hock, MO, et al. A randomized controlled trial comparing the hair apposition technique with tissue glue to standard suturing in scalp lacerations (HAT study). Ann Emerg Med. 2002; 40:19–26.

![]() 12. Khachemoune, A, et al, Dehisced clean wound. resuture it or steri-strip it. Dermatol Surg 2004; 30:431–432.

12. Khachemoune, A, et al, Dehisced clean wound. resuture it or steri-strip it. Dermatol Surg 2004; 30:431–432.

![]() 13. Krunic, AL, Weitzul, S, Taylor, RS, Running combined simple and vertical mattress suture. a rapid skin-everting stitch. Dermatol Surg 2005; 31:1325–1329.

13. Krunic, AL, Weitzul, S, Taylor, RS, Running combined simple and vertical mattress suture. a rapid skin-everting stitch. Dermatol Surg 2005; 31:1325–1329.

![]() 14. Mangram, AJ, et al. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999; 20:247–278. [1999].

14. Mangram, AJ, et al. Guideline for prevention of surgical site infection. Infect Control Hosp Epidemiol. 1999; 20:247–278. [1999].

15. Moreira, ME, Markovchick, VJ. Wound management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007; 25:873–899.

![]() 16. Moureau, NL. Is your skin prep technique up-to-date. Nursing. 2003; 33(11):17.

16. Moureau, NL. Is your skin prep technique up-to-date. Nursing. 2003; 33(11):17.

![]() 17. Reilly, J. Evidence-based surgical wound care on surgical wound infection. Br J Nurs. 2002; 11(16 Suppl):S4–S12.

17. Reilly, J. Evidence-based surgical wound care on surgical wound infection. Br J Nurs. 2002; 11(16 Suppl):S4–S12.

18. Singer, AJ, Dagum, AB. Current management of acute cutaneous wounds. N Engl J Med. 2008; 359:1037–1046.

19. Tanner, J, Woodings, D, Moncaster, K, Preoperative hair removal to reduce surgical site infection. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006; 3:CD004122, doi: 10. 1002/1465185858. [CD004122. pub3].

20. Waterbrook, AL, Germann, CA, Southall, JC. Is epinephrine harmful when used with anesthetics for digital nerve blocks. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 50:472–475.

21. Zehtabchi, S. The role of antibiotic prophylaxis for prevention of infection in patients with simple hand lacerations. Ann Emerg Med. 2007; 49(5):682–689.

![]() This procedure should be performed only by physicians, advanced practice nurses, and other healthcare professionals (including critical care nurses) with additional knowledge, skills, and demonstrated competence per professional licensure or institutional standard.

This procedure should be performed only by physicians, advanced practice nurses, and other healthcare professionals (including critical care nurses) with additional knowledge, skills, and demonstrated competence per professional licensure or institutional standard.

*Tracey Anderson would like to acknowledge the significant work done by the original chapter author, Peggy Kirkwood.