Intracompartmental Pressure Monitoring

Intracompartmental Pressure Monitoring

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

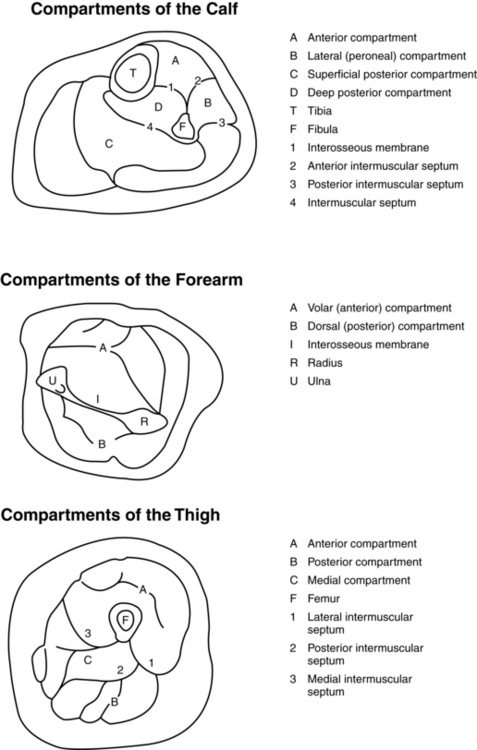

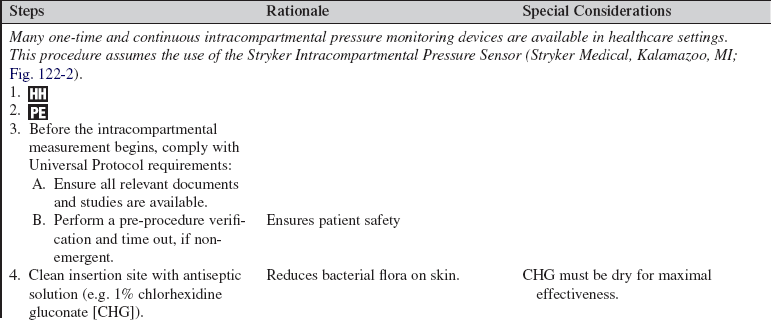

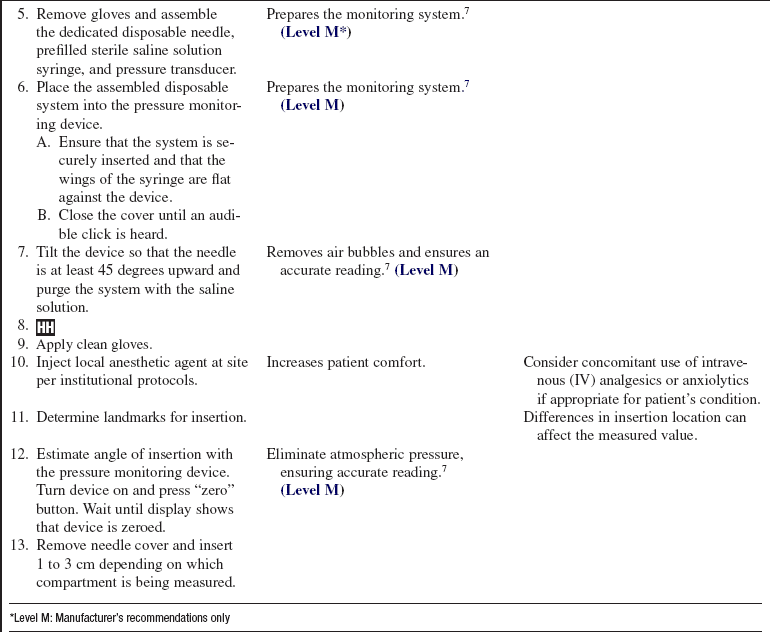

• Nurses performing intracomparmental pressure monitoring (IPM) must have detailed knowledge of the anatomy of the involved limb compartments (Fig. 122-1), including external landmarks associated with each compartment. Compartment syndrome may also develop in the abdomen (abdominal compartment syndrome [ACS]). For directions on measurement of bladder pressure, refer to Procedure 106.

• All clinicians involved with performing and assisting with the procedure should have knowledge of aseptic technique.

• Nurses should be credentialed in performing IPM. This should include supervised training in the techniques used for IPM and opportunities to maintain clinical competence.

• Clinicians should have a high index of suspicion that the patient is at risk for developing compartment syndrome. Etiologies can be divided into internal and external sources. Examples of internal causes include fractures, contusions, and edema formation associated with crush injuries or reperfusion injuries. External sources are generally related to compression of the limb and include such things as eschar from burn injuries, splints, casts, dressings, and immobility.1 Definitive treatment may be as simple as releasing a splint, cast, or dressing. More advanced treatment may require release of the compartment with an escharotomy or fasciotomy.

• The pathophysiology of compartment syndrome is related to compromised perfusion. Blood flow to any tissue or organ requires a sufficient perfusion pressure, which is generally calculated as the mean arterial pressure minus the intracompartmental pressure and should be 70 to 80 mm Hg.2 Therefore, as the mean arterial pressure decreases or the intracompartmental pressure increases, the perfusion to the tissue is reduced. Insufficient perfusion pressure may lead to ischemia and eventual necrosis of the tissues within the affected area.

• Normal compartment pressure within an unaffected compartment is considered less than 10 mm Hg.3,4 Clinically significant pressure changes are generally defined in one of two ways:

An absolute value of more than 30 mm Hg in the presence of other signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome. However, injury of the area may lead to elevations of the intracompartmental pressure in the absence of actual compartment syndrome.5 Positioning of the extremity may also cause elevations in intracompartmental pressure particularly when assessing dependent compartments.

An absolute value of more than 30 mm Hg in the presence of other signs and symptoms of compartment syndrome. However, injury of the area may lead to elevations of the intracompartmental pressure in the absence of actual compartment syndrome.5 Positioning of the extremity may also cause elevations in intracompartmental pressure particularly when assessing dependent compartments.

A delta compartment pressure (δp) of less than 30 mm Hg: the diastolic blood pressure minus the intracompartmental pressure. This measurement may be a more reliable indicator of the risk for development of compartment syndrome because it takes into account blood pressure.6,7

A delta compartment pressure (δp) of less than 30 mm Hg: the diastolic blood pressure minus the intracompartmental pressure. This measurement may be a more reliable indicator of the risk for development of compartment syndrome because it takes into account blood pressure.6,7

• Acute compartment syndrome is a true orthopedic emergency. Signs and symptoms can develop in as little as 2 hours after injury. Ischemic damage to muscles and nerves can start in 4 to 6 hours, with permanent damage occurring in 12 to 24 hours.3

EQUIPMENT

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the indications and rationale for performing this procedure to the patient and family.  Rationale: Explanation of the procedure may decrease patient and family anxiety and assist in patient cooperation.

Rationale: Explanation of the procedure may decrease patient and family anxiety and assist in patient cooperation.

• On the basis of institutional standard, obtain a formal consent, if the procedure is not emergent.  Rationale: Informed consent documents that the patient or family understands the explanation and need for the procedure.

Rationale: Informed consent documents that the patient or family understands the explanation and need for the procedure.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Review the patient’s history for conditions associated with the development of compartment syndrome.  Rationale: This review raises the index of suspicion for diagnosis of compartment syndrome.

Rationale: This review raises the index of suspicion for diagnosis of compartment syndrome.

• Clinical presentation of the compartment syndrome is traditionally listed with a series of “P’s”1,8:

Pain: Pain is the most commonly reported and earliest symptom of compartment syndrome but is often difficult to differentiate from that caused by the primary injury. Assessment of pain in patients with an altered level of consciousness is also difficult. Traditionally, pain is described as out of proportion to the injury or minimally responsive to analgesic interventions (e.g., intravenous narcotics). It is also exacerbated by active or passive stretching of the affected extremity.

Pain: Pain is the most commonly reported and earliest symptom of compartment syndrome but is often difficult to differentiate from that caused by the primary injury. Assessment of pain in patients with an altered level of consciousness is also difficult. Traditionally, pain is described as out of proportion to the injury or minimally responsive to analgesic interventions (e.g., intravenous narcotics). It is also exacerbated by active or passive stretching of the affected extremity.

Parasthesia: This sign precedes loss of motor function and occurs as pressure increases on the affected nerve. Early signs include loss of two point discrimination.

Parasthesia: This sign precedes loss of motor function and occurs as pressure increases on the affected nerve. Early signs include loss of two point discrimination.

Paresis or paralysis: This sign is a late finding that occurs as result of pressure on the nerve or necrosis of the affected muscles.

Paresis or paralysis: This sign is a late finding that occurs as result of pressure on the nerve or necrosis of the affected muscles.

Pulselessness: Pulselessness is another late finding, from occlusion of the arterioles by the increasing intracompartmental pressure. This sign also results in pallor or coolness of the affected extremity.

Pulselessness: Pulselessness is another late finding, from occlusion of the arterioles by the increasing intracompartmental pressure. This sign also results in pallor or coolness of the affected extremity.

Pressure: Tense edema in the affected extremity is often one of the initial signs appreciated in patients who have neurologic involvement or who are sedated. Pallor may be seen in the affected limb, which could also be mottled or cyanotic. Elevations in intracompartmental pressure are also considered part of the confirmatory diagnosis.

Pressure: Tense edema in the affected extremity is often one of the initial signs appreciated in patients who have neurologic involvement or who are sedated. Pallor may be seen in the affected limb, which could also be mottled or cyanotic. Elevations in intracompartmental pressure are also considered part of the confirmatory diagnosis.

Rationale: Presence of these symptoms may be sufficient to diagnose acute compartment syndrome in neurologically intact patients. In patients with an impaired level of consciousness (LOC), these symptoms signal the need for IPM.

Rationale: Presence of these symptoms may be sufficient to diagnose acute compartment syndrome in neurologically intact patients. In patients with an impaired level of consciousness (LOC), these symptoms signal the need for IPM.

Patient Preparation

• Explain steps of the procedure to the patient and family (if applicable). Answer any questions as they arise.  Rationale: Explanation reinforces understanding of previously presented information and may assist in allaying anxiety.

Rationale: Explanation reinforces understanding of previously presented information and may assist in allaying anxiety.

• Remove constricting dressings and bandages. Assist with the modification of splints, casts, and other devices on the affected extremity.  Rationale: Removal reduces external pressure on the tissue of the affected extremity.

Rationale: Removal reduces external pressure on the tissue of the affected extremity.

• Place the patient in the supine position with the extremity at the level of the heart.  Rationale: Access to the affected compartment is provided. Positioning the extremity above the heart may impede circulation, placing it in a dependent position, and may worsen edema.

Rationale: Access to the affected compartment is provided. Positioning the extremity above the heart may impede circulation, placing it in a dependent position, and may worsen edema.

• Consider administration of short-acting analgesic and/or anxiolytic.  Rationale: Analgesic and/or anxiolytic decreases patient discomfort during procedure.

Rationale: Analgesic and/or anxiolytic decreases patient discomfort during procedure.

References

![]() 1. Heppenstall, R, Scott, R, Spaega, A. A comparative study of the tolerance of skeletal muscle to ischaemia. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986; 68-A:820–828.

1. Heppenstall, R, Scott, R, Spaega, A. A comparative study of the tolerance of skeletal muscle to ischaemia. J Bone Joint Surg. 1986; 68-A:820–828.

![]() 2. Joint Commission. Universal protocol for preventing wrong site, wrong procedure, wrong person surgery,. http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/UniversalProtocol, 2003. [retrieved January 8, 2009, from].

2. Joint Commission. Universal protocol for preventing wrong site, wrong procedure, wrong person surgery,. http://www.jointcommission.org/PatientSafety/UniversalProtocol, 2003. [retrieved January 8, 2009, from].

3. Kakar, S, Firoozabodi, R, McKean, J, et al, Diastolic blood pressure in patients with tibia fractures under analgesia. implications for the diagnosis of compartment syndrome. J Orthop Trauma 2007; 21:99–103.

![]() 4. Ozkayin, N, Aktuglu, K. Absolute compartment pressure versus differential pressure for the diagnosis of compartment syndrome in tibial fractures. Int Orthop. 2005; 29:396–401.

4. Ozkayin, N, Aktuglu, K. Absolute compartment pressure versus differential pressure for the diagnosis of compartment syndrome in tibial fractures. Int Orthop. 2005; 29:396–401.

5. Prayson, MJ, Chen, JL, Hampers, D, et al. Baseline -compartment pressure measurements in isolated lower -extremity fractures without clinical compartment -syndrome. J Trauma. 2006; 60:1037–1040.

![]() 6. Seiler, JG, Womack, S, De L’Aune, WR, et al. Intracompartmental pressure measurements in the normal forearm. J Orthop Trauma. 1993; 7:414–416.

6. Seiler, JG, Womack, S, De L’Aune, WR, et al. Intracompartmental pressure measurements in the normal forearm. J Orthop Trauma. 1993; 7:414–416.

7. Stryker Medical : Intracomparmental pressure sensor, from package insert

![]() 8. Ulmer T. The clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the lower leg: are clinical findings predictive of the -disorder. J Orthop Trauma. 2002; 16:572–577.

8. Ulmer T. The clinical diagnosis of compartment syndrome of the lower leg: are clinical findings predictive of the -disorder. J Orthop Trauma. 2002; 16:572–577.

Walsh, CR. Musculoskeletal injuries. In: McQuillan KA, Makic MBF, Whalen E, eds. Trauma nursing: from resuscitation through rehabilitation. ed 4. St Louis: Elsevier; 2009:735.

Whiteside, TE, Haney, TC, Morimoto, M, et al. Tissue pressure measurements as a determinant for the need of fasciotomy. Clin Orthop Rel Res. 1975; 113:43–51.