Skin Graft Care

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Skin grafts, also called autografts, are sections of skin used to replace missing skin on a patient’s body. An autograft is created by taking a donor graft from one area of a patient’s body and transplanting it to a different area of the same patient’s body. It involves the surgical removal of a section of the epidermis and a portion of the dermis.1,8 This removal results in a new exposed wound area from which the donor graft was taken, called the donor site. The graft, a split-thickness skin graft (STSG), is applied over a clean, surgically excised wound that has been débrided of all nonviable tissue.

• An autograft is the only permanent treatment that can heal a large, full-thickness wound. Autografts may also be used to heal partial-thickness wounds with faster closure of the wound. The original wounds may be from a variety of causes (burns, infections, traumatic injury, etc).

• The autograft is harvested from an appropriate donor site on the patient’s body with a dermatome, a surgical instrument that shaves layers of skin at different depths to be grafted over the wound bed.

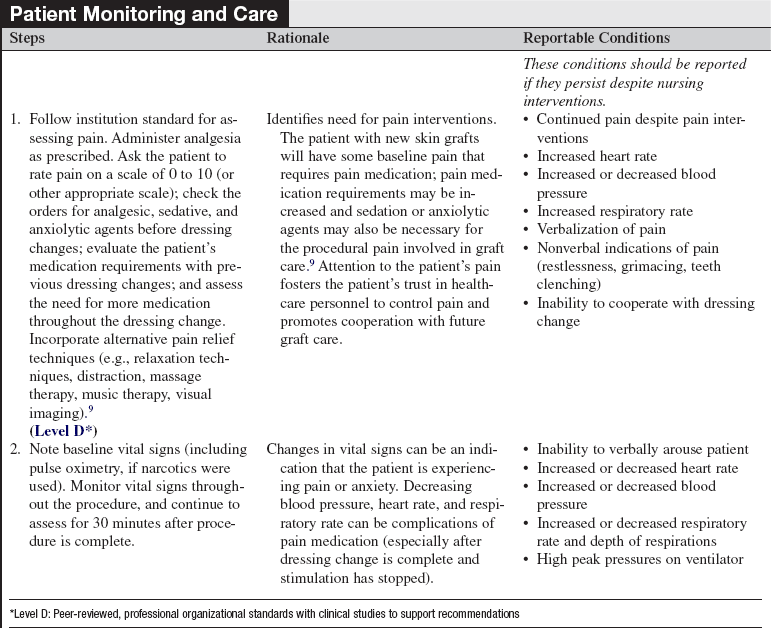

• The STSG is commonly meshed (Fig. 121-1) so that it can be stretched to cover approximately 1.5 to 9 times more surface area than the original donor site. The ability to stretch the donor graft is important when there is a limited availability of suitable donor sites or when the wound area that requires grafting is extensive. Meshing the donor skin creates spaces, or interstices, that allow for fluid to escape, which can assist with graft adherence.

Figure 121-1 Meshed split-thickness skin graft.

• Negative-pressure wound therapy (NPWT) is a mechanical wound care treatment that uses controlled negative pressure (via a machine, tubing, and sealed dressing) to accelerate wound healing. NPWT can also be used to enhance incorporation of a STSG mesh graft. The NPWT dressing is placed over the graft during surgery. A nonadherent dressing is used as a barrier for the graft to protect the graft from trauma and decrease overgrowth of granulation tissue formation.1

• Nonmeshed grafts, or sheet grafts, are used on the face, hands, and some joints because of cosmetic and functional concerns related to appearance and increased shrinkage.

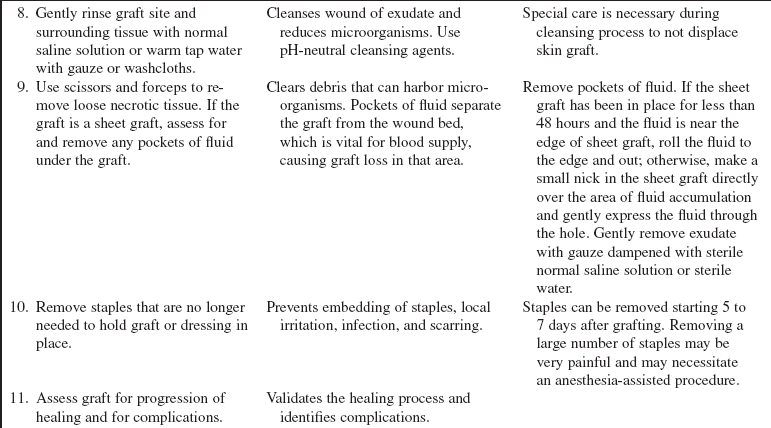

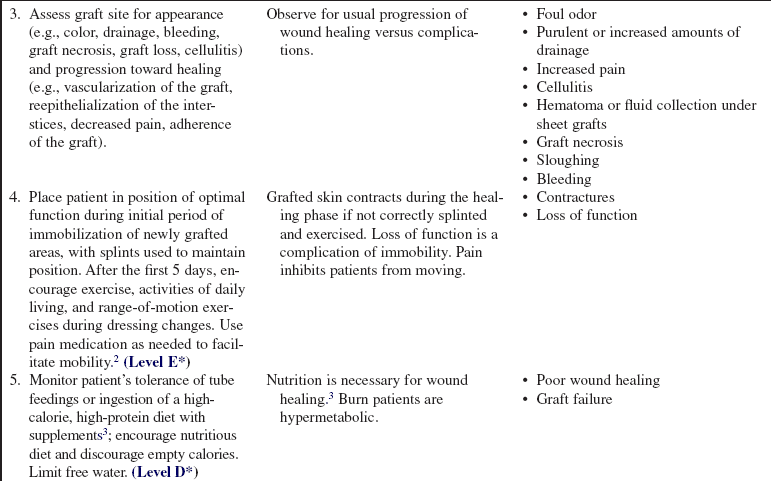

• A sheet graft covers the same amount of surface area as the donor site. Pockets of serous fluid or blood tend to accumulate under these grafts (the interstices of meshed grafts allow the fluid to escape) and separate the graft from the wound bed, which is vital for blood supply, resulting in failure of the graft to adhere or “take” to the wound bed. Evacuation of this fluid is imperative. Sheet grafts on the face, neck, and hands are generally inspected within the first 12 to 24 hours to look for fluid collections or graft dislodgement. If the sheet graft has been in place for less than 48 hours and the fluid is near the edge of sheet graft, the fluid can be rolled to the edge and out (Fig. 121-2).2

Figure 121-2 A, A no. 11 surgical blade and cotton-tipped applicator are used to blade a new sheet graft. Note that the blade is held so that the tip of the cutting surface comes into contact with only the graft. B, Cotton-tipped applicators are rolled gently over the graft toward the slit to express fluid that has collected between the graft and the wound bed surface. When deblebbing thick grafts, adequate-sized slits are important to avoid recurring buildup of fluid, which may jeopardize graft survivability and result in scarring. C, Blebs tend to recur in the same place. Vigilance about deblebbing at least once every 8 hours until bleb formation ceases is advisable. Documentation of bleb formation and location ensures that the next caregiver is aware of graft sites in need of close monitoring. (From Carrougher GJ: Burn care and therapy, St Louis, 1998, Mosby.)

• Caution should be used when evacuating fluid after vascularization of the graft begins to avoid disruption of the graft attachment endangering graft take. A more safe practice for removing fluid involves making a small nick in the sheet graft directly over the area of fluid accumulation and gently expressing the fluid through the hole. In either case, the fluid should be gently dabbed away with gauze dampened with sterile normal saline solution or sterile water.6 Seromas and hematomas tend to redevelop in the same areas, so careful charting should reflect location of any fluid pockets (blebs). Close monitoring of these areas should occur at least every 8 hours until bleb formation is no longer noted.

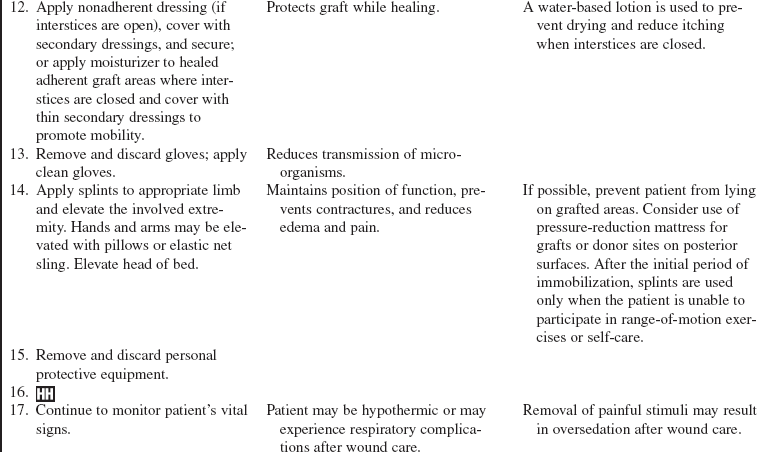

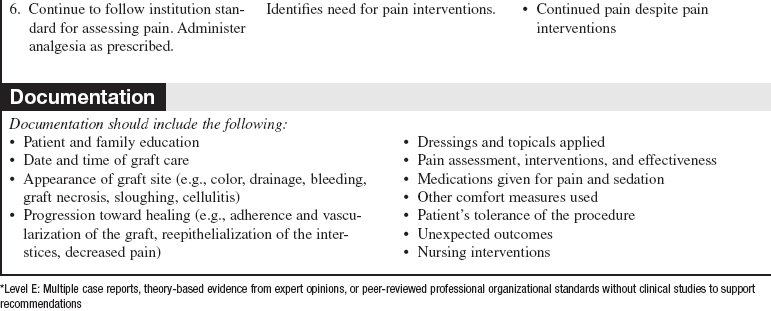

• In the operating room, all nonviable tissue is surgically excised to create a wound bed able to support a skin graft (Fig. 121-3); therefore, the grafted area should be observed for bleeding for the first 24 hours.

Figure 121-3 Meshed split-thickness skin graft covering the arm, with the remainder of the wound bed ready to be grafted.

• The goals after a graft placement are to protect the wound bed from infection and desiccation and to ensure that no movement (shearing) of the graft occurs while it is becoming vascularized. Neovascularization begins within the first 24 hours of surgery as capillaries grow up into the graft, securing the graft permanently to its new site. Either a barrier dressing (e.g., Biobrane allograft [UDL Laboratories, Rockford, IL]) protects the wound (with or without a bulky dressing added), or a minimal nonadherent dressing (e.g., Xeroform [McKesson Brand, San Francisco]) is used with a bulky dressing over the grafted tissue to act as the barrier to infection, prevent drying and shearing. The newly grafted tissue must be well protected from shearing forces for 5 to 7 days to allow for graft adherence to the wound bed. With meshed skin grafts, the interstices of the autograft fill with granulation tissue and the epidermis of the autograft migrates over the granulation tissues. Successful grafting is often expressed as a percentage of graft “take,” or adherence and vascularization of the graft to the new site.1,5

• Cultured epidermal autografts, most frequently used with burn injuries, are commercially available and are an option when the patient does not have enough unburned tissue for donor sites to cover the burn in a reasonable period of time.1,7 Cultured epidermal autografts are grown from a sample of the patient’s own epidermal cells in a laboratory. However, the cost is prohibitive, the grafts are extremely fragile, and successful take of the graft is much more likely if the burn team has experience with this treatment.3

• The use of artificial skin and other options for wound coverage has expanded in recent years. Currently, the use of these wound coverings is limited to providing temporary wound coverage or allowing for dermal regeneration while waiting for suitable donor sites for definitive wound closure with autografting.

• Allografts, also called homografts, are fresh or cyropreserved grafts from human donors. Allografts are the gold standard for temporary coverage of wounds. Allograft benefits include prevention of wound desiccation, promotion of granulation tissue, and decreased water and heat loss.1

• The use of Integra® Dermal Regeneration Template (Ethicon Endo-Surgery, Inc, Cincinnati, Ohio) has been shown to decrease length of stay (LOS) in severely injured burned adults.7 Integra® is a commercial bilayer dermal regeneration template system that is frequently used in burn centers to treat severe burns. Integra is composed of two layers. The first layer is made from cross-linked bovine collagen and chondroitin 6-sulfate (glycosaminoglycan) from shark collagen, which is a permanent dermal template that provides a scaffolding for the patient’s own dermis to grow into. The second layer, the outer layer, is a temporary synthetic polysiloxane polymer (silicone)covering that acts as an artificial epidermis until the patient is ready for autografting, usually 2 to 3 weeks after the Integra is placed. Because of enhanced dermal regeneration, the graft bed requires only a very thin meshed donor graft from the patient to heal the wound. This allows quicker healing of donor sites and the ability to reharvest from the same donor site multiple times, if necessary, in a short time period. Clinical trials have shown that the epidermal autograft over Integra usually heals without the formation of the meshed appearance typical of meshed autografts, thereby resulting in a better cosmetic outcome for the patient.5

• The graft is usually stapled or sutured in place, covered with a nonadherent dressing, and padded with a bulky bolster dressing to prevent mechanical dislodgement of the graft. Recent studies have shown that the use of fibrin sealants, a surgical hemostatic agent derived from human plasma, may be more effective than staples for adherence of sheet grafts.4

• After surgery, the graft is delicate, and care is taken to decrease trauma to the graft. If the graft is over a joint, the extremity may be immobilized to enhance graft take. The first dressing change is usually done after 3 to 5 days. Most centers use clean technique for dressing removal and donor-site cleansing and use sterile technique for dressing application only.6

• If a patient is allowed to mobilize after surgery, leg grafts must be supported with Ace wraps or other compressive dressings when the patient’s legs are dependent for the first 3 to 5 days after surgery to prevent capillary engorgement and hematoma formation beneath the graft. Grafted extremities should be elevated when the patient is supine.

• Initial healing of the grafted area should occur in 7 to 10 days. The graft area is immobilized for 4 to 5 days to prevent dislocation and shearing. Splints and immobilizers are used during this time to prevent disruption of grafts and to provide therapeutic positioning of extremities.

• Signs of successful graft take include vascularization of the graft, reepithelialization of the interstices, decreased pain, and adherence of the graft. Signs of complications include graft necrosis, graft loss, cellulitis, purulent drainage, and fever.

• Skin grafts contract during the healing and remodeling phases. Continuing mobility and proper positioning are vital to prevent contractures and loss of function. Self-care and range-of-motion exercises should be encouraged as soon as the graft is adherent. Once the wounds heal, pressure garments may be ordered to be worn at all times, except during bathing, to reduce hypertrophic scar formation.6

• Pain related to care of wounds is complicated by several components: background pain (pain that is continuously present), procedural pain (intermittent pain related to procedures and routine care), and anxiety. Unrelieved pain can lead to stress-related immunosuppression, increased potential for infection, delayed wound healing, and depression. The management of pain should be a multidimensional approach, including pharmacologic and nonpharmacologic methods, tailored to individual patient needs.8,9

• Burns greater than 20% total body surface area (TBSA) cause a hypermetabolic response that results from a loss of glycogen stores, increased gluconeogenesis, and increased lipid metabolism. In addition, dressing changes, loss of normal thermoregulatory mechanisms, surgical débridement, pain, and infection exacerbate the hypermetabolic response to injury. Therefore, estimating and meeting a patient’s nutritional needs is paramount to maximize wound healing.3

• Exposure of the healed skin graft to the sun should be avoided. The newly healed area is extremely sensitive to sunlight, and permanent discoloration can occur. To prevent discoloration, the patient should protect grafted areas with clothing or sunscreen. During the first year, as the patient’s graft matures, the risk for skin discoloration slowly decreases.

EQUIPMENT

• Personal protective equipment (i.e., gowns, mask, goggles)

• Warm tap water (sometimes sterile water or sterile normal saline [NS] solution is used for first dressing change)

• Nonadherent dressing/gauze (e.g., Adaptic [Johnson and Johnson, New Brunswick, NJ], Xeroform)

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure for skin graft care to patient and family.  Rationale: Explanation diminishes fear of the unknown and ensures that patient and family are knowledgeable about graft care.

Rationale: Explanation diminishes fear of the unknown and ensures that patient and family are knowledgeable about graft care.

• Inform patient and family that the grafted area needs to be protected for 5 to 7 days to encourage graft take and reduce the risk for mechanical trauma to graft site.  Rationale: Patient’s and family’s assistance in protecting the graft site is increased.

Rationale: Patient’s and family’s assistance in protecting the graft site is increased.

• Inform patient and family that the skin graft should not be exposed to the sun for approximately 1 year. Sunscreen and protective clothing should be used thereafter; some scarring and discoloration will occur but will improve over the first year. Explain that grafted area will not grow hair or be able to sweat because of permanent loss of these dermal appendages.  Rationale: The patient and family are prepared for changes that will be present after hospital discharge, and anxieties about body image are addressed.

Rationale: The patient and family are prepared for changes that will be present after hospital discharge, and anxieties about body image are addressed.

• Discuss the importance of proper positioning. Explain the need for continuing mobility through self-care and range-of-motion exercises as soon as the graft is adherent and throughout the healing phase.  Rationale: Education prevents contractures and loss of function associated with healing skin grafts.

Rationale: Education prevents contractures and loss of function associated with healing skin grafts.

• Assess family’s ability to provide care at home.  Rationale: Continued care of the wound is necessary after discharge.

Rationale: Continued care of the wound is necessary after discharge.

• As appropriate, provide detailed wound care instructions in writing and review with patient and family. Demonstrate exactly what to do, and have patient and family return demonstrations before the planned discharge. Continue to involve patient and family in the wound care for the remainder of the admission, and encourage them to ask questions. Provide positive feedback. Arrange for home care or clinic visits to follow-up on dressings and wound care.  Rationale: Education validates patient and family understanding and ability to perform wound care independently and allows time for them to develop a level of comfort. The opportunity to reinforce important points is provided.

Rationale: Education validates patient and family understanding and ability to perform wound care independently and allows time for them to develop a level of comfort. The opportunity to reinforce important points is provided.

• Teach patient and family about pain and pruritus medications as prescribed. Provide the name of a water-based lotion to apply to healed areas.  Rationale: Comfort at home is supported.

Rationale: Comfort at home is supported.

• Teach patient and family about signs and symptoms of infection and the importance of reporting these in a timely manner.  Rationale: The patient and family can recognize problems early so that appropriate measures can be instituted by the healthcare team.

Rationale: The patient and family can recognize problems early so that appropriate measures can be instituted by the healthcare team.

• Emphasize the importance of wearing pressure garments and splints.  Rationale: Scar formation and contractures are reduced.

Rationale: Scar formation and contractures are reduced.

• Schedule follow-up appointments and provide the name of someone to call with any problems.  Rationale: This information is necessary for further care and follow-up.

Rationale: This information is necessary for further care and follow-up.

• Work with vocational rehabilitation counselor to formulate plan for patient’s return to work.  Rationale: Depending on the severity of the patient’s injuries, the patient may be physically unable to return to former employment or may need assistance with job modifications and accommodations. Developing a back-to-work plan based on any new limitations increases the patient’s chance of successfully returning to work.

Rationale: Depending on the severity of the patient’s injuries, the patient may be physically unable to return to former employment or may need assistance with job modifications and accommodations. Developing a back-to-work plan based on any new limitations increases the patient’s chance of successfully returning to work.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess vital signs, including temperature.  Rationale: Baseline vital signs allow for comparison during and after the procedure to evaluate patient tolerance and need for pain medication.

Rationale: Baseline vital signs allow for comparison during and after the procedure to evaluate patient tolerance and need for pain medication.

• Evaluate for success of graft take: vascularization of the graft; reepithelialization of the interstices; decreased pain; adherence of the graft  Rationale: Graft success or adherence to wound is assessed with each episode of care to evaluate healing.

Rationale: Graft success or adherence to wound is assessed with each episode of care to evaluate healing.

• Monitor for signs of complications: fever; elevated white blood cell count; cellulitis; increased purulent drainage or saturation of the secondary dressing.  Rationale: Baseline and ongoing assessment for signs of graft failure to include possible infection are important for early identification of complications to minimize graft loss.

Rationale: Baseline and ongoing assessment for signs of graft failure to include possible infection are important for early identification of complications to minimize graft loss.

• Compare patient’s rate of healing with expected rate of wound of healing for number of days after skin graft.  Rationale: Initial healing of grafted area should occur in 7 to 10 days.

Rationale: Initial healing of grafted area should occur in 7 to 10 days.

• Determine adequacy of the pain control regimen by asking the patient to rate the pain on a scale of 0 to 10 (or other scale as appropriate), both before wound care (background pain) and during the dressing change.  Rationale: An individualized plan for pain control should be in place for background and procedural pain. In addition to the traditional use of pain and anxiety medications, alternative therapies should be included (e.g., relaxation techniques, distraction, massage therapy, music therapy). The patient’s medication requirements should decrease as the grafted area heals.

Rationale: An individualized plan for pain control should be in place for background and procedural pain. In addition to the traditional use of pain and anxiety medications, alternative therapies should be included (e.g., relaxation techniques, distraction, massage therapy, music therapy). The patient’s medication requirements should decrease as the grafted area heals.

• Assess patient’s level of function in the grafted area.6  Rationale: Skin grafts contract during the healing phase, and immobility enhances loss of function. The patient should be encouraged to continue normal movement and range-of-motion exercises after graft take has been established.6

Rationale: Skin grafts contract during the healing phase, and immobility enhances loss of function. The patient should be encouraged to continue normal movement and range-of-motion exercises after graft take has been established.6

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Notify other appropriate healthcare providers who need to assess the graft (e.g., physician) or perform a task (e.g., range-of-motion exercises by physical therapist) of the time of dressing change.  Rationale: Organization of care allows important assessment and intervention to take place without causing extra pain and stress to the patient.

Rationale: Organization of care allows important assessment and intervention to take place without causing extra pain and stress to the patient.

• Premedicate the patient with pain medication and any sedation and anxiolytic medications as prescribed. Allow an appropriate amount of time for medications to begin to take effect before starting wound care.  Rationale: Premedication reduces pain and anxiety and allows time for medication to take effect and promote optimal comfort for the patient. Patient trust and compliance with procedure are encouraged.

Rationale: Premedication reduces pain and anxiety and allows time for medication to take effect and promote optimal comfort for the patient. Patient trust and compliance with procedure are encouraged.

References

1. Bryant, R, Nix, D, Acute & chronic wounds,. ed 3. Mosby, St Louis, 2006:361–390.

![]() 2. Carrougher, GJ. Burn care and therapy,, ed 1. St Louis: Mosby; 1998.

2. Carrougher, GJ. Burn care and therapy,, ed 1. St Louis: Mosby; 1998.

![]() 3. Flynn, MB. Nutritional support for the burn-injured patient. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16(1):139–144.

3. Flynn, MB. Nutritional support for the burn-injured patient. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16(1):139–144.

4. Gibran, N, Luterman, A, Herndon, D, et al, Comparison of fibrin sealant and staples for attaching split-thickness -autologous sheet grafts in patients with deep partial- or full-thickness burn wounds. a phase 1/2 clinical study. J Burn Care Res. 2007; 28(3):401.

![]() 5. Heimbach, D, et al, Artificial dermis for major burns. a multi-center randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 1988; 208:313–320.

5. Heimbach, D, et al, Artificial dermis for major burns. a multi-center randomized clinical trial. Ann Surg 1988; 208:313–320.

![]() 6. Honari, S. Topical therapies and antimicrobials in the management of burn wounds. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16(1):1–11.

6. Honari, S. Topical therapies and antimicrobials in the management of burn wounds. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16(1):1–11.

7. Jeng, JC, Fidler, PE, Sokolich, JC, et al. Seven years’ experience with Integra as a reconstructive tool. J Burn Care Res. 2007; 28(1):120–126.

8. Makic, MBF, Mann, E. Burn injuries. In: McQuillan K, Makic MBF, Whalen E, eds. Trauma nursing: from -resuscitation through rehabilitation. ed 4. St Louis: Elsevier; 2009:865–888.

![]() 9. Montgomery, RK. Pain management in burn injury. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16(1):39–49.

9. Montgomery, RK. Pain management in burn injury. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16(1):39–49.

Barret, JP, Herndon, DN. Effects of burn wound excision on bacterial colonization and invasion. Plast Reconstruct Surg. 2003; 111:744–750.

Branski, LK, Herndon, DN, Pereira, C, et al, Burn and wound care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16 (1)

Foster, K, Richey, K, Wound wise. the story on partial-thickness skin grafts. Nurs Made Incredibly Easy. 2008; 6(2):19–21.

Heimbach, DM, et al. Multicenter postapproval clinical trial of Integra Dermal Regeneration Template for burn treatment. J Burn Care Rehab. 2003; 24:42–48.

Herndon, DN, Total burn care. ed 3. Saunders, London, 2007.

Integra Dermal Regeneration Template. www.integra-ls.com/products, January 14, 2010 [retrieved from].

Nowlin, A. The delicate business of burn care. RN. 2006; 69(1):52–58.

Osborn, K, Critical care. nursing burn injuries. Nurs Manage. 2003; 34(5):49–56.

Pham, C, Greenwood, J, Cleland, H, et al, Bioengineered skin substitutes for the management of burns. a systematic review. Burns. 2007; 33(8):946–957.

Saffle, JR, Covering massive burn injuries. integra-ting and interpreting the data. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35(11):2661–2662.

Zhang, X, Jeschke, MG, Longitudinal assessment of integra in primary burn management. a randomised pediatric clinical trials. Crit Care Med. 2007; 35(11):2615–2623.