Burn Wound Care

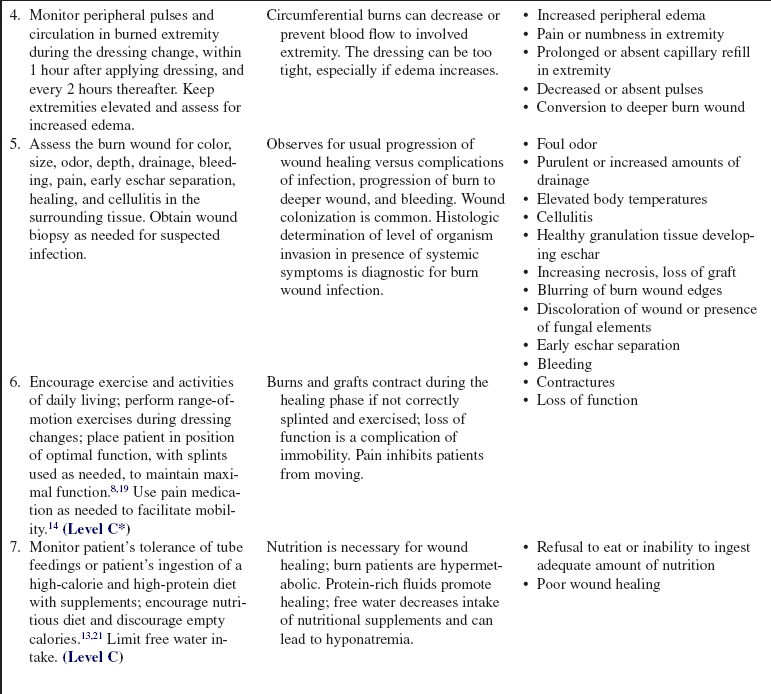

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

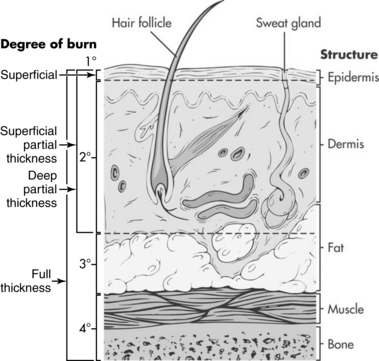

• Burns destroy the structural integrity of the skin, disrupting its normal functions of regulating temperature, maintaining fluid status, protecting against infection, covering nerve endings, and establishing identity.2 The skin is composed of two layers, the epidermis and the dermis, and is supported by a subcutaneous layer that is rich in blood vessels (Fig. 120-1).

The epidermis is the outermost layer. It is capable of rapid regeneration through division of cells closest to the dermis; older epidermal cells are pushed outward as the epidermis is regenerated. The epidermis provides a barrier to the environment, containing melanocytes (protection from the sun) and Langerhans cells (protection against foreign organisms).

The epidermis is the outermost layer. It is capable of rapid regeneration through division of cells closest to the dermis; older epidermal cells are pushed outward as the epidermis is regenerated. The epidermis provides a barrier to the environment, containing melanocytes (protection from the sun) and Langerhans cells (protection against foreign organisms).

The dermis contains blood vessels, sensory fibers (for pain, touch, pressure, and temperature), collagen, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands. Epidermal cells line deep dermal structures (hair follicles and sweat glands); these epidermal elements provide the ability for the skin to regenerate (the more epidermal cells remaining in the wound bed, the faster the healing).

The dermis contains blood vessels, sensory fibers (for pain, touch, pressure, and temperature), collagen, sebaceous glands, and sweat glands. Epidermal cells line deep dermal structures (hair follicles and sweat glands); these epidermal elements provide the ability for the skin to regenerate (the more epidermal cells remaining in the wound bed, the faster the healing).

• The depth of burns has historically been classified as first-degree (into epidermis), second-degree (into dermis), or third-degree (through skin into subcutaneous tissue; Table 120-1).1,2

Table 120-1

Depth Characteristics of Burn Wounds

| Type | Physical Characteristics | Healing |

| Superficial burn (first-degree): Destruction of epidermis, usually caused by overexposure to sun or brief exposure to hot liquid. This type of injury is not included in calculation of burn size. | Red; hypersensitive; no blisters. | Injured layers peel away from totally healed skin at 5 to 7 days without residual scarring. |

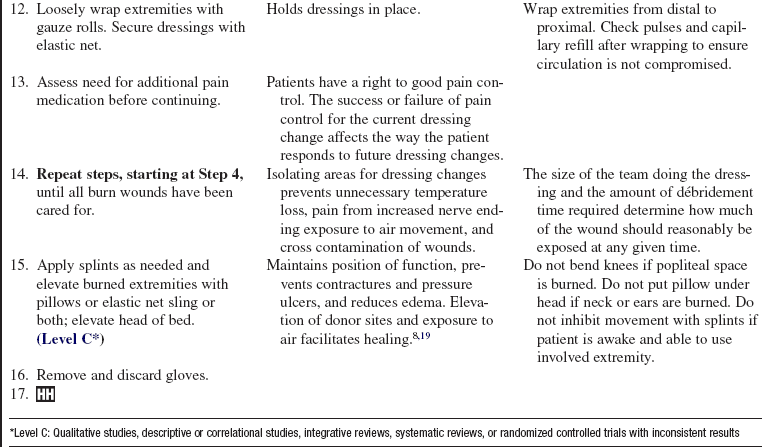

| Superficial partial-thickness burn (superficial second-degree): Destruction of epidermis and upper dermis. Usually results from scalding or brief contact with hot objects. | Blistered; very moist; red or pink in color; exquisitely painful; capillary refill intact. | Reepithelializes from epidermal appendages in 7 to 14 days. Usually has minimal scarring but variable repigmentation. |

| Deep partial-thickness burn (deep second-degree): Destruction of epidermis through to lower dermis. May result from grease or longer contact with hot objects. | Mottled pink to white; drier than superficial burns; less sensitive to pinprick; does not blanch to pressure; hair follicles and sweat glands intact. | Slower regeneration from epidermal elements: 14 to 21+ days in absence of grafting. Prone to hypertrophic scars and contracture formation. May require grafting to reduce healing time and complications. |

| Full-thickness burn (third-degree): Destruction of epidermis and all of dermis. Results from exposure to flames, chemicals that are not immediately washed, electrical injury, or prolonged contact with heat source. | Dry; leathery and firm to touch; pearly white, brown, or charred in appearance; no blanching to pressure; no pain, may see thrombosed vessels. | Incapable of self-regeneration. Preferred treatment is early excision and autografting. |

First-degree, or superficial, burns extend only partially through the epidermis, thereby maintaining the barrier function of the skin. These burns are not included when estimating the percentage of total body surface area burned (%TBSA) because they do not result in an open wound.

First-degree, or superficial, burns extend only partially through the epidermis, thereby maintaining the barrier function of the skin. These burns are not included when estimating the percentage of total body surface area burned (%TBSA) because they do not result in an open wound.

Second-degree burns extend into the dermis and can be superficial (loss of the epidermis and part of the dermis) or deep (destruction of most of the dermis). They are also referred to as partial-thickness burns because they extend partially through the skin (Fig. 120-2). These wounds heal by epithelialization from epidermal cells remaining in the dermis. Shallow wounds are associated with rapid healing and less scarring. Deep wounds may result in slow-healing (more than 21 days) and fragile wounds prone to hypertrophic scarring. For that reason, surgical excision of partial-thickness wounds that affect functional and cosmetic areas and application of skin grafts may be preferable.

Second-degree burns extend into the dermis and can be superficial (loss of the epidermis and part of the dermis) or deep (destruction of most of the dermis). They are also referred to as partial-thickness burns because they extend partially through the skin (Fig. 120-2). These wounds heal by epithelialization from epidermal cells remaining in the dermis. Shallow wounds are associated with rapid healing and less scarring. Deep wounds may result in slow-healing (more than 21 days) and fragile wounds prone to hypertrophic scarring. For that reason, surgical excision of partial-thickness wounds that affect functional and cosmetic areas and application of skin grafts may be preferable.

A third-degree, or full-thickness, burn involves complete destruction of the dermis. Because the skin is unable to regenerate, the dead tissue is removed and the wound is grafted with skin from another part of the patient’s own body (autograft).2 The grafted wound loses epidermal appendages and is unable to sweat, maintain lubrication, or protect from sun exposure after healing (Fig. 120-3).

A third-degree, or full-thickness, burn involves complete destruction of the dermis. Because the skin is unable to regenerate, the dead tissue is removed and the wound is grafted with skin from another part of the patient’s own body (autograft).2 The grafted wound loses epidermal appendages and is unable to sweat, maintain lubrication, or protect from sun exposure after healing (Fig. 120-3).

• The depth of a burn wound is directly related to the temperature intensity and the duration of contact with the burning agent. The burning agent can be thermal (i.e., flame, contact, or scald), chemical, or electrical. An inhalation injury should always be suspected if the patient was in an enclosed space with a fire; mortality rate is significantly increased when burns are compounded by smoke inhalation.4

• The burn injury produces three zones of injury: the zone of coagulation (cellular death), zone of stasis (vascular impairment, potentially reversible tissue injury), and zone of hyperemia (increased blood flow and inflammatory response). Decreased perfusion of the burn wound can cause the zone of stasis to deteriorate, deepening the initial wound. This progressive destruction can be minimized by providing adequate oxygenation and fluid resuscitation, alleviating pressure on the injured tissue, maintaining local and systemic warmth, and decreasing edema by elevating the burned area.1

• Assess for areas where full-thickness eschar is circumferential. Because of the inelastic nature of eschar, it may act like a tourniquet as edema develops, requiring surgical release (escharotomy) to prevent circulatory or respiratory compromise (Fig. 120-4).

Figure 120-4 Escharotomy of the leg to improve circulation.

• Monitor pulses, capillary refill, and sensation distal to circumferential eschar. Signs and symptoms that indicate a need for escharotomy include cyanosis of distal unburned skin, unrelenting deep tissue pain, progressive paresthesias, and progressive decrease or absence of pulse.1

• Adequacy of respiratory excursion must be assessed because circumferential eschar of the trunk can lead to decreased tidal volume and agitation (Fig. 120-5).1

• Escharotomy is performed at the bedside by a physician, with a scalpel or electrocautery used to cut the eschar longitudinally. Bleeding should be minimal because only dead tissue is cut; any bleeding can be controlled with sutures, silver nitrate sticks, collagen packing, or electrocautery. Pain is usually managed with small intravenous doses of opiates and benzodiazepines.

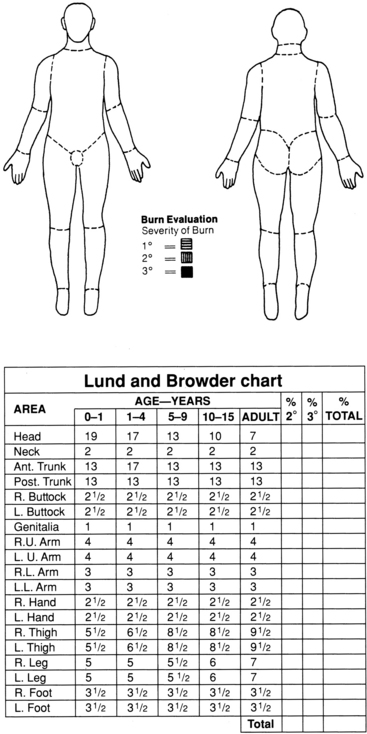

• Burn size may be determined with several methods.20

The rule of nines may be used to quickly calculate burn size. In an adult, the head and neck and each upper extremity represent 9% of the patient’s body surface area. The anterior trunk, posterior trunk, and each leg represent 18% of the patient’s body surface area. This rule only applies to adults; infants and young children have much larger heads in proportion to body size.

The rule of nines may be used to quickly calculate burn size. In an adult, the head and neck and each upper extremity represent 9% of the patient’s body surface area. The anterior trunk, posterior trunk, and each leg represent 18% of the patient’s body surface area. This rule only applies to adults; infants and young children have much larger heads in proportion to body size.

The Lund and Browder chart (Fig. 120-6) breaks the body into smaller areas and takes into consideration the proportional differences of persons of different ages.12

The Lund and Browder chart (Fig. 120-6) breaks the body into smaller areas and takes into consideration the proportional differences of persons of different ages.12

Figure 120-6 The Lund and Browder chart is used to assess and graphically document size and depth of the burn wound.

The rule of the palm notes that the patient’s hand may be used as a template to represent roughly 1% of the TBSA.

The rule of the palm notes that the patient’s hand may be used as a template to represent roughly 1% of the TBSA.

• The inflammatory response causes a massive fluid shift to the interstitial space during the first 24 hours, with mobilization of fluid starting after 72 hours. Fluid resuscitation with a balanced salt solution is based on the patient’s weight and burn size (partial-thickness and full-thickness wounds).17 Large wounds are prone to huge evaporative water losses that require close monitoring of volume status.

• Effective resuscitation results in adequate urinary output (30 to 50 mL/hr or 0.5 to 1.0 mL/kg/hr) and mean arterial blood pressure of at least 60 mm Hg as surrogate markers of end-organ perfusion and hemodynamic stability.17

• Burns of specific anatomic areas need special consideration. Assess eyes for injury and treat chemical exposure with copious normal saline solution irrigation; treat burned ears with a topical antimicrobial cream and protect from pressure by eliminating use of pillows or dressings about the head; elevate burned extremities; consider the need for an indwelling urinary catheter in the patient with perineal burns; and shave hair growing through the burn wounds. Two burned surfaces that contact each other need dressings between them to prevent fusing as they heal (e.g., between toes, skin folds).

• Emergency treatment of thermal injuries includes initially cooling the burned skin with tepid water (never with ice) while recognizing the importance of preventing hypothermia.1 In preparation for transfer, the airway should be assessed and 100% oxygen administered; large-bore intravenous (IV) access should be established and fluid resuscitation started; patients should be on nothing by mouth (NPO) status; wounds should be wrapped with a clean, dry sheet and possibly blanket; pain medication should be given in small IV doses, with recognition that coexisting injuries or medical conditions exacerbate the effects of opiates; tetanus prophylaxis should be administered; and all initial treatment should be documented.1

• Initial treatment of chemical burns includes removing saturated clothing, brushing off any powdered chemical, and continuously irrigating involved skin with copious amounts of water for 20 to 30 minutes. Neutralizing chemical burns with another chemical is contraindicated because the procedure generates heat. Burned eyes must be irrigated with large volumes of normal saline solution followed by an eye examination.1 Some chemicals are absorbed systemically through burn wounds; contact the local poison control center to determine whether further treatment is indicated.2 Ensure all providers wear appropriate personal protective equipment to prevent unintentional chemical exposure.

• Tar can be removed with mineral oil, a petrolatum-based ointment, or solvent.16

• Electrical injuries (Fig. 120-7) result when the body becomes part of the pathway for the electrical current. Deep burns may occur from tissue resistance where the patient contacted the electrical source and where the patient was grounded. Initially of greater concern than the burns is the high incidence of cardiac dysrhythmias, myoglobinuria resulting in acute tubular necrosis, and neurologic sequelae. Monitoring electrocardiographic (ECG) results, increasing urine output to 100 mL/hr in the presence of dark port-colored urine, assessing for associated trauma, and establishing baseline neurologic status are vital in the treatment of the electrical injury patient.1,20

Figure 120-7 Entry site of an electrical burn.

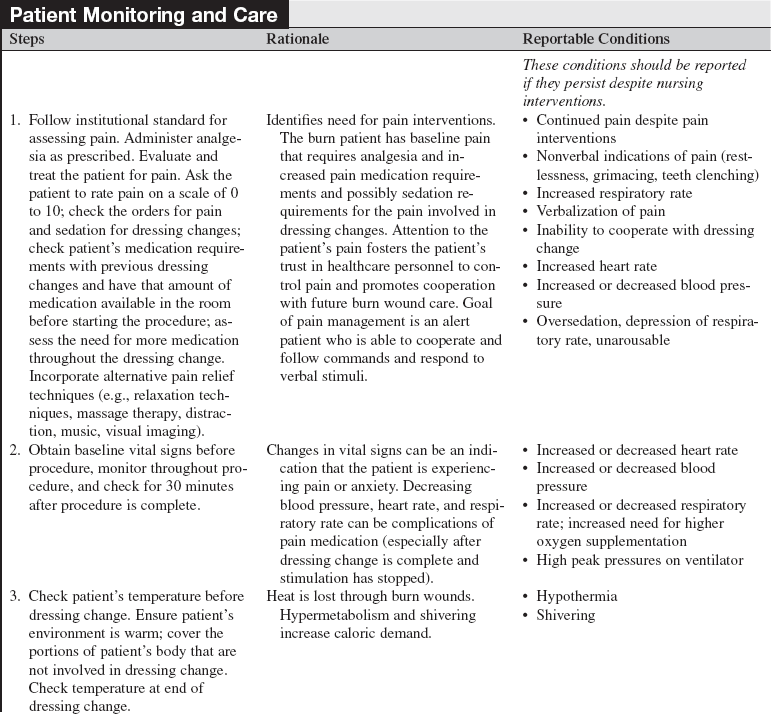

• Criteria for transferring patients to a specialized burn care facility have been adopted by the American Burn Association and the American College of Surgeons. These criteria are listed in Table 120-2.

Table 120-2

Criteria for Patient Transfer to a Specialized Burn Care Facility

Partial-thickness burns on more than 10% TBSA

Burns that involve the face, hands, feet, genitalia, perineum, or major joints

Third-degree burns in any age group

Electrical burns, including lightning injury

Chemical burns

Inhalation injury

Burn injury in patients with preexisting medical disorders that could complicate management, prolong recovery, or affect mortality

Any patient with burns and concomitant trauma (such as fractures) in which the burn injury poses the greatest risk for morbidity or mortality

Burned children in hospitals without qualified personnel or equipment to care for children

Burn injury in patients who will need special social, emotional, or long-term rehabilitative intervention

(Adopted From Committee on Trauma, American College of Surgeons: Guidelines for the operation of burn centers resources for optimal care of the injured patient, Chicago, 2006, American College of Surgeons, 79-86) .

• Care of the burn wound and associated healing are determined by the extent and depth of the injury and the overall condition of the patient.

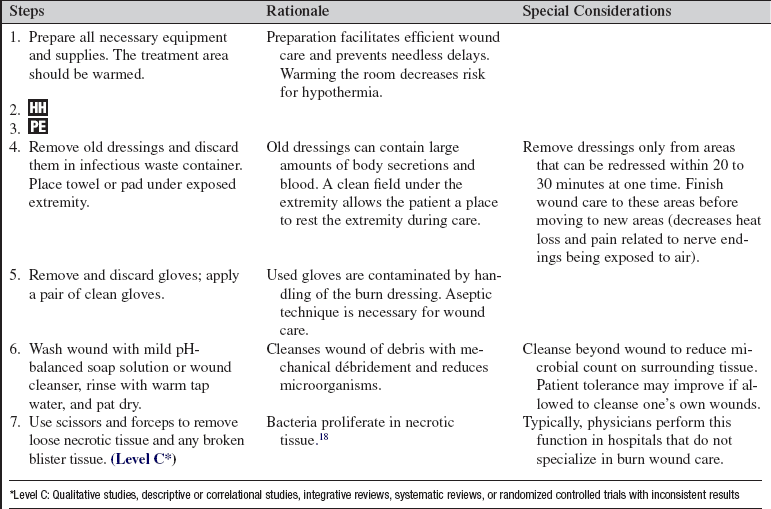

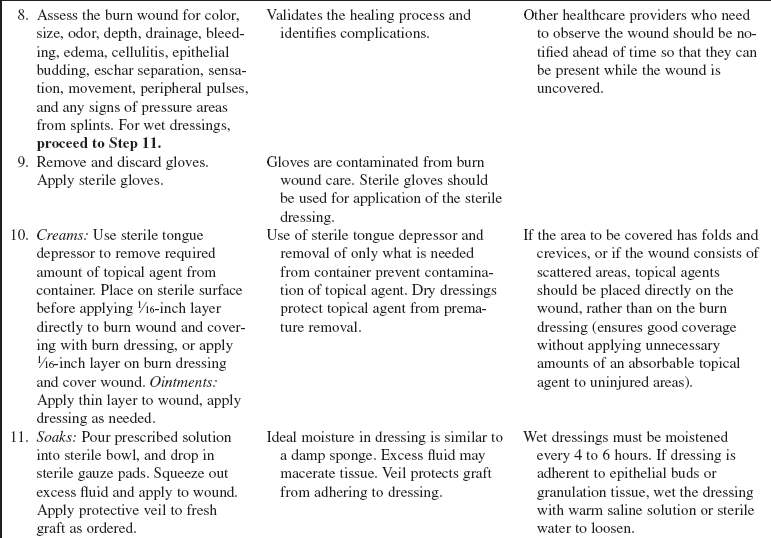

• Most burn centers use clean technique for dressing removal and wound cleansing, with sterile technique for sterile dressing application only.2

• Wound care should be done in a warm area. Many burn units have replaced traditional hydrotherapy tanks with shower tables for large wound care procedures to allow water run-off, thus decreasing leaching of electrolytes and minimizing wound exposure to perineal-contaminated water. Emergency equipment must always be immediately available during hydrotherapy procedures. As wounds decrease in size and patients approach discharge, bathtubs and showers offer reasonable options for wound cleansing.

• Initial wound cleansing requires thorough débridement of all devitalized tissue. Blisters are generally unroofed.18 Use of dry gauze is effective to gently remove burned tissue, with use of a slow and deliberate wiping motion. Wash the wounds with gentle pH neutral liquid soap solution or wound cleanser and pat dry with clean towels.

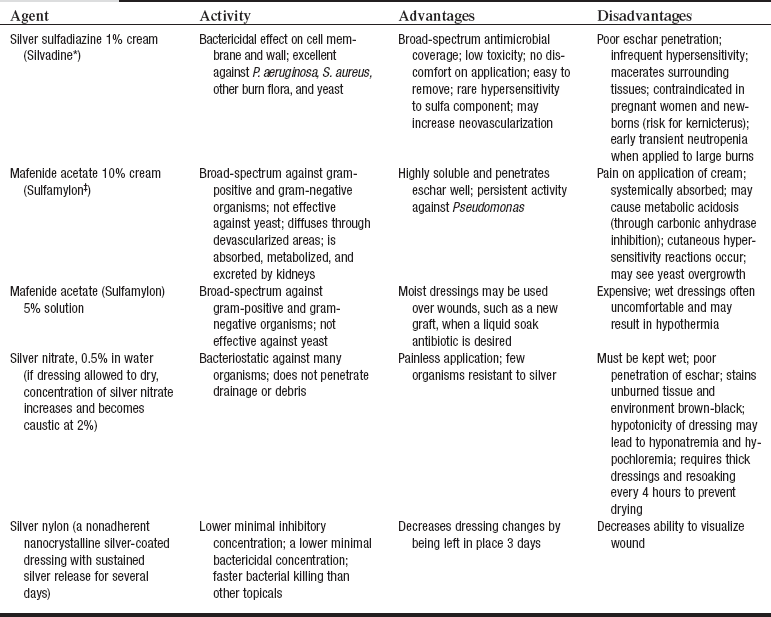

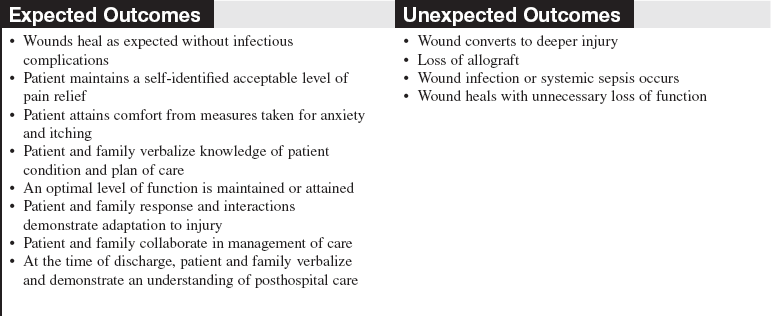

• Topical antimicrobial agents limit bacterial proliferation and fungal colonization in burn wounds. The three most commonly used agents are 1% silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene, Monarch Pharmaceuticals, Inc., Bristol, TN), 10% mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon, UDL Laboratories, Inc., Rockford, IL), and 0.5% silver nitrate solution (Table 120-3).7 Systemic antibiotics are not routinely administered to burn patients because of the high risk for development of antibiotic resistance.15

• Eschar is a leathery layer of devitalized tissue that covers full-thickness burns. Bacterial action causes eschar to separate from the wound bed. However, the use of topical antimicrobial agents and early excision has minimized the nurse’s involvement in eschar removal.

• Survival rates for burn patients are markedly improved with early excision and grafting.6 The most important predictors of mortality are the patient age and the extent of the burn, with the presence of inhalation injury and comorbidity crucial factors. Although the burn wound has the most obvious potential for infection, the lower respiratory tract is the most common site of infection and carries the highest incidence of sepsis and death.4

• An autograft (skin graft taken from the patient) is the only treatment that can heal a full-thickness burn wound.11 Wounds with higher than 105 organisms per gram of tissue impede graft adherence, so expedient grafting is desirable.15

• Burn wound management accomplishes three primary goals: protect the wound, reduce metabolic demand, and provide comfort.

• A débrided full-thickness wound may be protected from infection and drying through the use of biologic dressings when donor sites are not available for autografting. Allograft, or homograft, refers to the use of “nonself” human skin grafts; such a graft becomes vascularized by the patient and risks rejection if it stays in place too long. Xenograft, or heterograft, is nonhuman skin obtained from commercial pigskin (porcine) processing companies; it forms a collagen bond with the wound and protects it for a period of time until donor sites are available for autografting. Porcine xenograft may be placed over clean partial-thickness wounds to protect the wound while it heals beneath the xenograft.11

• Integra (Integra Lifesciences Corporation, Plainsboro, NJ) is an acellular matrix composite graft that may be placed on débrided full-thickness burns. Capillaries and collagen grow into this matrix in about 3 weeks, forming a neodermis, which is then grafted with the patient’s own epidermal cells. The matrix is slowly biodegradable and cannot be detected with wound biopsy after complete healing.11 This allows for improved wound coverage and use of thinner donor sites but requires two surgeries. Thinner autografts allow more rapid healing of donor sites and produce less hypertrophic donor site scarring.

• Biosynthetic dressings such as Biobrane (UDL Laboratories, Inc., Rockford, IL) have been used to cover clean partial-thickness wounds to facilitate healing.11,22 Biobrane is a two-layer, semisynthetic dressing composed of knitted-elastic nylon fabric that is mechanically bonded to a thin, Silastic, semipermeable membrane and coated with collagen polypeptides.22 As the wound heals beneath, the dressing can be peeled away.22

• Topical antimicrobial agents are used to reduce wound colonization. Commonly used creams include silver sulfadiazine (Silvadene) and 10% mafenide acetate (Sulfamylon), antibacterial ointments such as bacitracin, and liquid soaks such as mafenide acetate 5% solution and 0.5% silver nitrate.7 Creams and ointments are applied every 12 hours or as needed to cover the wound. Dry protective dressings prevent premature removal of the topical. Damp gauze dressings saturated with antimicrobial solution are changed every 24 hours, but dressings require moistening (“wet-down”) every 4 to 6 hours to ensure activity of agent.

• Negative-pressure wound therapy may be used to maintain fresh graft placement, improve wound bed vascularization, and reduce microbial activity.20

• The burn patient’s condition is hypermetabolic until burn wounds are closed and healing is complete. Increased caloric and protein requirements for wound healing are usually met through nasogastric or nasojejunal tube feeding to maintain mucosal integrity in large burns. Zinc and vitamin C have also been shown to be important in wound healing. Current research is evaluating the role of arginine and fish oil in decreasing infections,13 glutamine’s role in maintaining mucosal integrity and reducing infection,13 and insulin’s ability to preserve muscle mass.21 Additional treatments include use of β-blockade9 to reduce metabolic demand and oxandrolone10 to increase anabolism.

• Burn patients should be encouraged to consume a high-protein diet. Supplementation with high-calorie nutritional drinks facilitates meeting energy needs. Large quantities of free water should be discouraged because risk for hyponatremia is high after a large burn.

• During wound care because heat lost through the wound, along with shivering, increases the metabolic rate.

• An individualized plan for pain control should be in place for both background pain (pain that is continuously present), breakthrough pain (associated with activity of daily living), and procedural pain (intermittent pain related to procedures).5,14 Unrelieved pain can lead to stress-related immunosuppression, an increased potential for infection, delayed wound healing, and depression. Subcutaneous and intramuscular injections should be avoided because absorption is poor and unreliable as a result of edema. Intravenous administration of medication is preferred in critically ill patients; oral medication is preferred in noncritical patients with a functioning gastrointestinal system.5,14 As the wound heals, the patient has more discomfort from itchiness and less discomfort from pain.14 A moisturizing lotion prevents drying and reduces pruritus. Nonpharmacologic techniques can be learned to assist with the management of pain and itch.3,5,14

• Burn wounds contract during the healing phase. Self-care and range-of-motion exercises are encouraged. Stretching exercises and proper positioning are vital to prevent contractures and loss of function.8 Static splinting is sometimes added to maintain sustained stretch.8 Hypertrophic scar formation is countered through the use of topical silicone gel sheeting and pressure garments worn 24 hours a day until the scars mature and soften (6 to 18 months).19 Keloids, if they form, may require surgery, steroid injections, and pressure treatment.19

• Grafts and donor sites on the lower extremities require support during healing when the patient is out of bed. Application of elastic bandages to extremities may prevent pooling of venous blood, permanent discoloration, or skin breakdown.

• The burn wound should not be exposed to the sun for a year because new scars sunburn easily.

• Patients should be instructed to select clothing that blocks sun and to use sunscreen on exposed grafts, generally for life.

EQUIPMENT

• Personal protective equipment as needed (e.g., gown, mask, goggles)

• Mild pH-neutral liquid soap, as ordered

• Scissors and forceps (clean and sterile)

• Sterile dressings as needed (e.g. gauze, Exu-dry [Smith & Nephew, St. Petersburgh, FL])

• Rolled dressing, gentle tape, or netting to secure dressings

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Provide detailed wound care instructions in writing or on videotape or DVD. Demonstrate wound care, and have patient and family return the demonstration before the planned discharge. Continue to involve patient and family in wound care for the remainder of the admission, and encourage them to ask questions. Provide positive feedback. Arrange for home care or clinic visits to follow up on wound care.  Rationale: Education validates patient and family understanding and ability to perform wound care and allows time for them to develop a level of comfort. The opportunity to reinforce important points is provided.

Rationale: Education validates patient and family understanding and ability to perform wound care and allows time for them to develop a level of comfort. The opportunity to reinforce important points is provided.

• Explore resources the patient will have for wound care at home (e.g., availability of running water, tub versus shower).  Rationale: This measure ensures that the patient is knowledgeable about care based on what adjustments need to be made at home.

Rationale: This measure ensures that the patient is knowledgeable about care based on what adjustments need to be made at home.

• Simplify wound care and assess the family’s ability to provide care at home.  Rationale: Continued care of the wound may be necessary after discharge.

Rationale: Continued care of the wound may be necessary after discharge.

• Teach patient and family about signs and symptoms of infection and the importance of reporting these in a timely manner.  Rationale: The patient and family can recognize problems early so that appropriate measures can be instituted by the healthcare provider.

Rationale: The patient and family can recognize problems early so that appropriate measures can be instituted by the healthcare provider.

• Teach patient and family about pain control; assess the patient’s personal acceptable level of pain.  Rationale: Education and assessment decrease concerns about pain, facilitate individualized pain relief plan, and foster cooperation with care.

Rationale: Education and assessment decrease concerns about pain, facilitate individualized pain relief plan, and foster cooperation with care.

• Teach patient and family about pain management, including types of medications prescribed, timing of medications in relation to wound care, and nonpharmacologic pain strategies.5  Rationale: Comfort at home is supported.

Rationale: Comfort at home is supported.

• Provide instruction to the patient and family about the normal changes seen in the wound, including epithelial islands, healing margins, dryness on epithelialization, epidermal fragility on shearing, hypervascularization of the healed wound, and venous congestion in the dependent wound.  Rationale: Anxiety about appearance is reduced.

Rationale: Anxiety about appearance is reduced.

• Teach patient and family about care of healed burns, including medications to reduce itching,3,14 use of nonperfumed moisturizers, protection from shear, and protection from sun exposure for a minimum of a year.  Rationale: Education reduces complications and promotes patient satisfaction.

Rationale: Education reduces complications and promotes patient satisfaction.

• Explain the rationale to the patient and family about the wearing and care of pressure garments.  Rationale: Pressure garments need to fit properly to reduce scar formation, and they can be difficult to apply.19

Rationale: Pressure garments need to fit properly to reduce scar formation, and they can be difficult to apply.19

• Discuss the importance of mobility and proper positioning (e.g., splinting) on function. Self-care (activities of daily living) and range-of-motion exercises should be encouraged during the healing phase.  Rationale: Contractures associated with healing skin, improper positioning, and immobility are prevented.

Rationale: Contractures associated with healing skin, improper positioning, and immobility are prevented.

• Identify caloric needs for healing and suggest appropriate nutritional supplements.  Rationale: Metabolic needs are increased for months after discharge, and a balanced diet facilitates gain of muscle mass versus adipose tissue.

Rationale: Metabolic needs are increased for months after discharge, and a balanced diet facilitates gain of muscle mass versus adipose tissue.

• Inform patient and family that nightmares, alterations in body image, and psychologic disturbances are experienced by many burned patients.20 Provide resources, including someone to follow up with, if desired.  Rationale: Information increases awareness of these problems and reassures patient and family that these experiences, although unpleasant, are not abnormal.

Rationale: Information increases awareness of these problems and reassures patient and family that these experiences, although unpleasant, are not abnormal.

• Provide patient and family with follow-up appointments and someone to call with any problems.  Rationale: Necessary information for further care and follow-up is provided.

Rationale: Necessary information for further care and follow-up is provided.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess vital signs, including temperature.  Rationale: Baseline vital signs allow for comparison during and after the procedure to evaluate patient tolerance, normothermia, and adequacy of pain medication.

Rationale: Baseline vital signs allow for comparison during and after the procedure to evaluate patient tolerance, normothermia, and adequacy of pain medication.

• Evaluate for signs of healing, including the following:

Reepithelialization from epithelial islands within wound

Reepithelialization from epithelial islands within wound

Compare patient’s level of healing with expected level of healing for number of days after burn.

Compare patient’s level of healing with expected level of healing for number of days after burn.

Rationale: Healing should occur within a predictable time frame determined by the depth of burns, unless complications occur.

Rationale: Healing should occur within a predictable time frame determined by the depth of burns, unless complications occur.

• Evaluate for the following signs and symptoms of infection20:

Development of eschar or early eschar separation

Development of eschar or early eschar separation

Increase in burn size or depth

Increase in burn size or depth

Rationale: Infection can result in delayed wound healing, prolonged hospitalization, and death.

Rationale: Infection can result in delayed wound healing, prolonged hospitalization, and death.

• Monitor for distal circulation (pulses, pain, color, sensation, movement, and capillary refill) to areas with circumferential burns and increased edema.  Rationale: Edema and circumferential burns impede distal circulation and cause worsening tissue perfusion and cell death.

Rationale: Edema and circumferential burns impede distal circulation and cause worsening tissue perfusion and cell death.

• Determine patient’s understanding of pain management strategies. Assess patient’s pain level on a standardized pain scale (such as the 0 to 10 scale) before, during, and after the procedure. Explore discrepancies between the patient’s level of pain and desired level of pain.  Rationale: An individualized plan for pain control should be in place for background, breakthrough, and procedural pain.5,14 In addition to the traditional use of pain and anxiety medications, alternative therapies should be included (e.g., relaxation techniques, distraction, massage therapy, music therapy). The patient’s needs change based on changes in the wound (e.g., healing, débridement, conversion to deeper wound).

Rationale: An individualized plan for pain control should be in place for background, breakthrough, and procedural pain.5,14 In addition to the traditional use of pain and anxiety medications, alternative therapies should be included (e.g., relaxation techniques, distraction, massage therapy, music therapy). The patient’s needs change based on changes in the wound (e.g., healing, débridement, conversion to deeper wound).

• Evaluate patient’s general level of function, particularly in burned areas.  Rationale: An individualized plan for range-of-motion exercises, positioning, and splinting should be made to optimize the patient’s level of function. Burns contract during the healing phase, and immobility enhances loss of function.

Rationale: An individualized plan for range-of-motion exercises, positioning, and splinting should be made to optimize the patient’s level of function. Burns contract during the healing phase, and immobility enhances loss of function.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure the patient understands procedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Notify other appropriate healthcare providers who need to assess the burn wound (e.g., physician) or perform a task (e.g., quantitative wound biopsies, range-of-motion exercises by physical therapist) of time of dressing change.  Rationale: Organization of care allows important assessment and intervention to take place without causing extra pain and stress to the patient.

Rationale: Organization of care allows important assessment and intervention to take place without causing extra pain and stress to the patient.

• After checking previous requirements for patient comfort during the dressing change, premedicate the patient with pain medication and any sedative as prescribed, allowing an appropriate amount of time before starting wound care.  Rationale: Premedication allows time for medication to take effect and promotes optimal comfort for the patient.

Rationale: Premedication allows time for medication to take effect and promotes optimal comfort for the patient.

• Consider synergistic effects of opioids, sedatives, and drugs that affect the central nervous system (CNS). Closely monitor patient 30 to 60 minutes after wound care procedure is completed.  Rationale: Stimulatory effects that counteract CNS depression are reduced after wounds are covered; decreased noxious stimuli and respiratory depression may occur.

Rationale: Stimulatory effects that counteract CNS depression are reduced after wounds are covered; decreased noxious stimuli and respiratory depression may occur.

References

![]() 1. American Burn Association. Advanced burn life support provider course. Chicago: American Burn Association; 2005.

1. American Burn Association. Advanced burn life support provider course. Chicago: American Burn Association; 2005.

2. Bessey, TQ. Wound care. In: Herndon DN, ed. Total burn care. ed 3. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:127–135.

3. Brooks, JP, et al, Scratching the surface. managing the itch associated with burnsa review of current knowledge. Burns 2008; 34:751–760.

4. Demling, RH, Smoke inhalation lung injury. an update. Eplasty 2008; 16:254–282.

5. Faucher, L, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of pain. J Burn Care Res. 2006; 27:659–668.

6. Guo, F, et al, Management of burns over 80% of total body surface area. a comparative study. Burns 2008; [doi:10. 1016/j. burns. 2008. 05. 021].

![]() 7. Honari, S. Topical therapies and antimicrobials in the management of burn wounds. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16:1–11.

7. Honari, S. Topical therapies and antimicrobials in the management of burn wounds. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16:1–11.

8. Huang, T. Management of contractural deformities involving the axilla (shoulder), elbow, hip, knee, and ankle joints in burn patients. In: Herndon DN, ed. Total burn care. ed 3. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:727–740.

9. Ipaktchi, K, Arbabi, S. Advances in burn critical care. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34:S239–S244.

10. Jeschke, MG, et al. The effect of oxandrolone on the endocrinologic, inflammatory, and hypermetabolic responses during the acute phase postburn. Ann Surg. 2007; 246:351–362.

11. Lineen, E, et al. Biologic dressings in burns. J Craniofac Surg. 2008; 19:923–928.

![]() 12. Lund, CC, Browder, NC. The estimate of areas of burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1944; 79:352–358.

12. Lund, CC, Browder, NC. The estimate of areas of burns. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1944; 79:352–358.

13. Masters, B, Wood, F, Nutrition support in burns. is there consistency in practice. J Burn Care Res 2008; 29:561–571.

14. Meyer, WJ, et al. Management of pain and other discomforts in burned patients. In: Herndon D, ed. Total burn care. ed 3. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:797–818.

15. Polavarapu, N, et al. Microbiology of burn wound infections. J Craniofac Surg. 2008; 19:899–902.

16. Pham, TN, et al, Evaluation of the burn wound. management decisionsHerndon D, ed.. Total burn care. ed 3. Saunders Elsevier, London, 2007:119–126.

17. Pham, TN. American Burn Association practice guidelines burn shock resuscitation. J Burn Care Res. 2008; 29:257–266.

18. Sargent, RL, Management of blisters in the partial-thickness burn. an integrative research review. J Burn Care Res 2006; 27:66–81.

19. Serghiou, MA, et al. Comprehensive rehabilitation of the burn patient. In: Herndon D, ed. Total burn care. ed 3. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:620–651.

20. Stout, LR. Burns. In: Carlson KK, ed. AACN advanced critical care nursing. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:1212–1260.

21. Wanek, S, Wolf, SE. Metabolic response to injury and role of anabolic hormones. Curr Opin Clin Nutr Metab Care. 2007; 10:272–277.

22. Whitaker, IS, et al, A critical evaluation of the use of Biobrane as a biologic skin substitute. a versatile tool for the plastic and reconstructive surgeon. Ann Plastic Surg 2008; 60:333–337.

Broughton, G, et al, Wound healing. an overview. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 117:1eS–32eS.

Flynn MB, ed.. Burn and wound care. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am, 16. 2004:1–185.

Makic, MBF, Mann, E. Burn injuries. In: McQuillan K, Makic MBF, Whalen E, eds. Trauma nursing: resuscitation through rehabilitation. Philadelphia: Elsevier; 2009:865–888.