Suctioning: Endotracheal or Tracheostomy Tube

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Endotracheal and tracheostomy tubes are used to maintain a patent airway and to facilitate mechanical ventilation. The presence of these artificial airways, especially endotracheal tubes, prevents effective coughing and secretion removal, necessitating periodic removal of pulmonary secretions with suctioning. In acute care situations, suctioning is always performed as a sterile procedure to prevent hospital-acquired pneumonia.

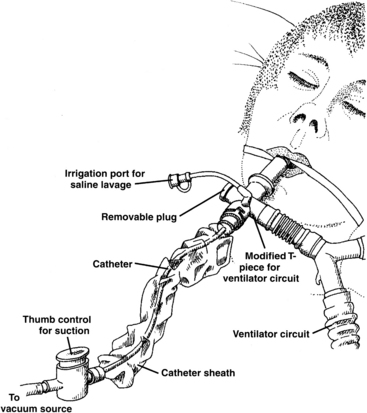

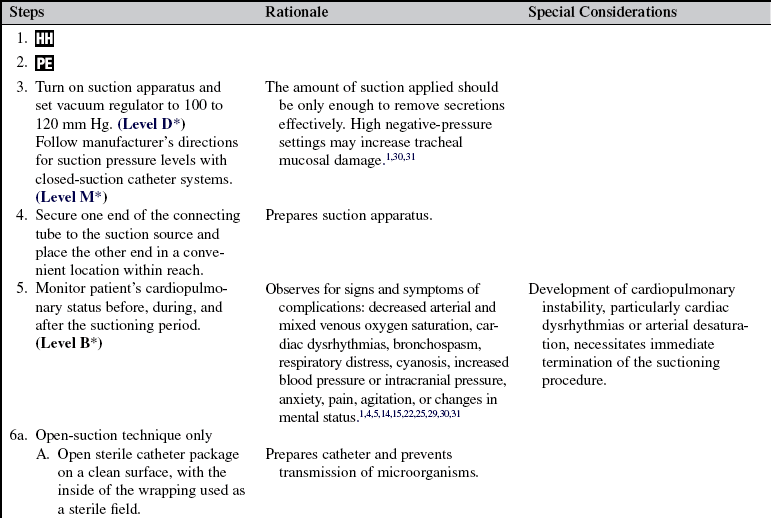

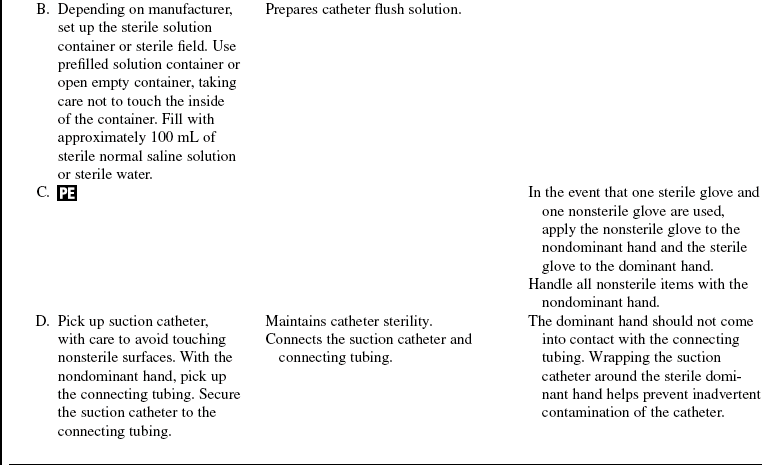

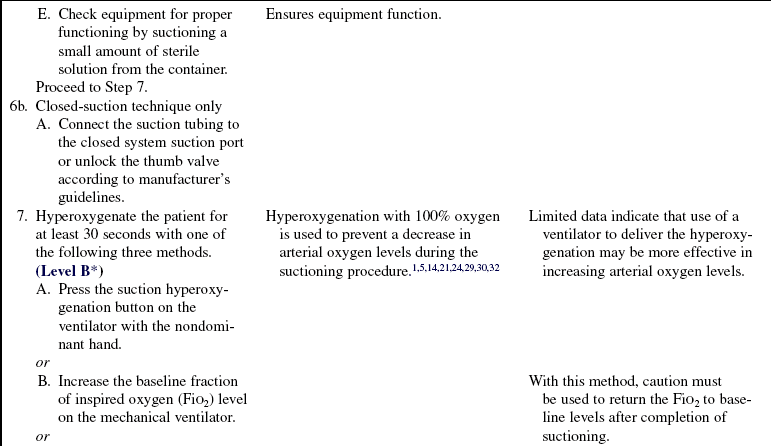

• Suctioning is performed with one of two basic methods. In the open-suction technique, after disconnection of the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube from any ventilatory tubing or oxygen sources, a single-use suction catheter is inserted into the open end of the tube. In the closed-suction technique, also referred to as in-line suctioning, a multiple-use suction catheter inside a sterile plastic sleeve is inserted through a special diaphragm attached to the end of the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube (Fig. 12-1). The closed-suction technique allows for the maintenance of oxygenation and ventilation support, which may be beneficial in patients with moderate to severe pulmonary insufficiency. In addition, the closed-suction technique decreases the risk for aerosolization of tracheal secretions during suction-induced coughing. Use of the closed-suction technique should be considered in patients with cardiopulmonary instability during suctioning with the open technique, who have high levels of positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP; >10 cm H2O) or inspired oxygen (greater than 80%) or both, who have grossly bloody pulmonary secretions, or in whom airborne transmission of disease, such as active pulmonary tuberculosis, is suspected.

• Indications for suctioning include the following:

Secretions in the artificial airway

Secretions in the artificial airway

Suspected aspiration of gastric or upper airway secretions

Suspected aspiration of gastric or upper airway secretions

Auscultation of adventitious lung sounds (rhonchi) over the trachea or main-stem bronchi or both

Auscultation of adventitious lung sounds (rhonchi) over the trachea or main-stem bronchi or both

Increase in peak airway pressures when patient is on mechanical ventilation

Increase in peak airway pressures when patient is on mechanical ventilation

Increase in respiratory rate or frequent coughing or both

Increase in respiratory rate or frequent coughing or both

Gradual or sudden decrease in arterial blood oxygen (PaO2), arterial blood oxygen saturation (SaO2), or arterial saturation via pulse oximetry (SpO2) levels

Gradual or sudden decrease in arterial blood oxygen (PaO2), arterial blood oxygen saturation (SaO2), or arterial saturation via pulse oximetry (SpO2) levels

Sudden onset of respiratory distress, when airway patency is questioned

Sudden onset of respiratory distress, when airway patency is questioned

• Suctioning of airways should be performed only for a clinical indication and not as a routine fixed-schedule treatment.

• Hyperoxygenation always should be provided before and after each pass of the suction catheter into the endotracheal tube, whether with the open or closed suctioning method.

• Suctioning is a necessary procedure for patients with artificial airways. When clinical indicators of the need for suctioning exist, there is no absolute contraindication to suctioning. In situations in which the development of a suctioning complication would be poorly tolerated by the patient, strong evidence of a clinical need for suctioning should exist.

• Complications associated with suctioning of artificial airways include the following:

Cardiac dysrhythmias (premature contractions, tachycardias, bradycardias, heart blocks)

Cardiac dysrhythmias (premature contractions, tachycardias, bradycardias, heart blocks)

Decreases in mixed venous oxygen saturation (SVO2)

Decreases in mixed venous oxygen saturation (SVO2)

Increased intracranial pressure

Increased intracranial pressure

• Tracheal mucosal damage (epithelial denudement, hyperemia, loss of cilia, edema) occurs during suctioning when tissue is pulled into the catheter tip holes. These areas of damage increase the risk of infection and bleeding. Use of special-tipped catheters, low levels of suction pressure, or intermittent suction pressure has not been shown to decrease tracheal mucosal damage with suctioning.

• Postural drainage and percussion may improve secretion mobilization from small to large airways in diseases with large mucus production (e.g., cystic fibrosis, bronchitis).

• Adequate systemic hydration and supplemental humidification of inspired gases assist in thinning secretions for easier aspiration from airways. Instillation of a bolus of normal saline solution does not thin secretions, may cause decreases in arterial and mixed venous oxygenation, and may contribute to lower airway contamination from the mechanical dislodgment of bacteria within the artificial airway or from contamination of saline solution during instillation.26

• The suction catheter should not be any larger than half of the internal diameter of the endotracheal or tracheostomy tube.

EQUIPMENT

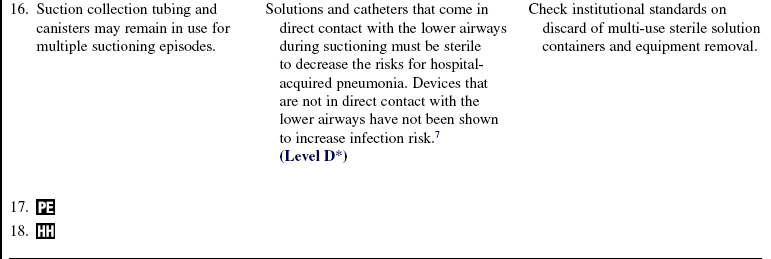

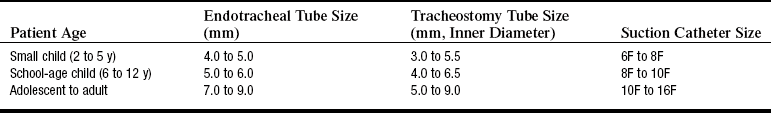

Suction catheter of appropriate size (Table 12-1)

Suction catheter of appropriate size (Table 12-1)

Table 12-1

Guideline for Catheter Size for Endotracheal and Tracheostomy Tube Suctioning*

*This guide should be used as an estimate only. Actual sizes depend on the size and individual needs of the patient. Always follow manufacturer’s guidelines.

Adapted from St John RE, Seckel M: Airway management. In AACN protocols for practice: care of the mechanically ventilated patient series, Sudbury, MA, 2007, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 41.

Sterile saline or sterile water solution

Sterile saline or sterile water solution

Source of suction (wall mounted or portable)

Source of suction (wall mounted or portable)

Manual self-inflating manual resuscitation bag-valve-device connected to an oxygen flow meter, set at 15 L/min (not required with use of the ventilator to deliver hyperoxygenation breaths)

Manual self-inflating manual resuscitation bag-valve-device connected to an oxygen flow meter, set at 15 L/min (not required with use of the ventilator to deliver hyperoxygenation breaths)

Additional equipment (to have available depending on patient need) includes the following:

Closed-suction setup with a catheter of appropriate size (see Table 12-1)

Closed-suction setup with a catheter of appropriate size (see Table 12-1)

Sterile saline solution lavage containers (5 to 10 mL)

Sterile saline solution lavage containers (5 to 10 mL)

Suction catheter (individually packaged) for oral and nasal suctioning

Suction catheter (individually packaged) for oral and nasal suctioning

Source of suction (wall mounted or portable)

Source of suction (wall mounted or portable)

Goggles and mask, or mask with eye shield, and gown if necessary

Goggles and mask, or mask with eye shield, and gown if necessary

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure for endotracheal or tracheostomy tube suctioning.  Rationale: The explanation reduces anxiety.

Rationale: The explanation reduces anxiety.

• Explain that suctioning may be uncomfortable and could cause the patient to experience shortness of breath.  Rationale: This information reduces anxiety and elicits patient cooperation.

Rationale: This information reduces anxiety and elicits patient cooperation.

• Explain the patient’s role in assisting with secretion removal by coughing during the procedure.  Rationale: This information encourages cooperation and facilitates removal of secretions.

Rationale: This information encourages cooperation and facilitates removal of secretions.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess for signs and symptoms of airway obstruction:

•  Rationale: Physical signs and symptoms result from inadequate gas exchange associated with airway obstruction.

Rationale: Physical signs and symptoms result from inadequate gas exchange associated with airway obstruction.

• Note peak airway pressures on the ventilator.  Rationale: These pressures indicate potential secretions in the airway, increasing resistance to gas flow.

Rationale: These pressures indicate potential secretions in the airway, increasing resistance to gas flow.

• Evaluate SaO2 and SpO2 levels.  Rationale: These values indicate potential secretions in the airway, decreasing gas exchange.

Rationale: These values indicate potential secretions in the airway, decreasing gas exchange.

• Assess signs and symptoms of inadequate breathing patterns:

•  Rationale: Respiratory distress is a late sign of lower airway obstruction.

Rationale: Respiratory distress is a late sign of lower airway obstruction.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

Rationale: This communication evaluates and reinforces understanding of previously taught information.

• Assist the patient in achieving a position that is comfortable for the patient and nurse, generally semi-Fowler’s or Fowler’s, with the bed elevated to the nurse’s waist level.  Rationale: This positioning promotes comfort, oxygenation, and ventilation and reduces strain.

Rationale: This positioning promotes comfort, oxygenation, and ventilation and reduces strain.

• Secure additional personnel to assist with the self-inflating manual resuscitation bag-valve-device to provide hyperoxygenation (open-suction technique only).  Rationale: Two hands are necessary to inflate the self-inflating manual resuscitation bag-valve-device for adult tidal volume levels (>600 mL).

Rationale: Two hands are necessary to inflate the self-inflating manual resuscitation bag-valve-device for adult tidal volume levels (>600 mL).

References

![]() 1. AARC Clinical Practice Guideline. Endotracheal suctioning of mechanically ventilated adults and children with artificial airways. Respir Care. 1993; 38:500–504.

1. AARC Clinical Practice Guideline. Endotracheal suctioning of mechanically ventilated adults and children with artificial airways. Respir Care. 1993; 38:500–504.

2. AACN Practice Alert. Oral care in the critically ill. www.aacn.org/WD/Practice/Docs/Oral_Care_in_the_Critically_Ill.pdf, 2006. [retrieved August 9, 2008, from].

![]() 3. Akgul, S, Akyolcu, N. Effects of normal saline on endotracheal suctioning. J Clin Nurs. 2002; 11:826–830.

3. Akgul, S, Akyolcu, N. Effects of normal saline on endotracheal suctioning. J Clin Nurs. 2002; 11:826–830.

4. Arroyo-Novoa, CM, et al, Pain related to tracheal suctioning in awake acutely and critically ill adults. a descriptive study. Intensive Crit Care Nurs 2007; 24:20–27.

5. Bourgault, AM, et al. Effects of endotracheal tube suctioning on arterial oxygen tension and heart rate variability. Biol Res Nurs. 2006; 7:268–278.

6. Celik, SA, Kanan, N, A current conflict. use of isotonic sodium chloride solution on endotracheal suctioning in critically ill patients. Dimens Crit Care Nurs 2006; 25:11–14.

![]() 7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Guidelines for prevention of health-care-associated pneumonia, 2003 . Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. MMWR. 2004; 53(No. RR-3):1–35.

7. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Guidelines for prevention of health-care-associated pneumonia, 2003 . Recommendations of CDC and the Healthcare infection Control Practices Advisory Committee. MMWR. 2004; 53(No. RR-3):1–35.

![]() 8. Czarnik, R, et al. Differential effects of continuous versus intermittent suction on tracheal tissue. Heart Lung. 1991; 20:144–151.

8. Czarnik, R, et al. Differential effects of continuous versus intermittent suction on tracheal tissue. Heart Lung. 1991; 20:144–151.

9. Ellstrom, K. The pulmonary system. In: Alspach J, ed. Core curriculum for critical care nursing. ed 6. St Louis: Elsevier; 2006:45–183.

![]() 10. Glass, C, et al. Nurse performance of hyperoxygenation. Heart Lung. 1991; 20:299.

10. Glass, C, et al. Nurse performance of hyperoxygenation. Heart Lung. 1991; 20:299.

![]() 11. Glass, C, et al. Nurses’ ability to achieve hyperinflation and hyperoxygenation with a manual resuscitation bag during endotracheal suctioning. Heart Lung. 1993; 22:158–165.

11. Glass, C, et al. Nurses’ ability to achieve hyperinflation and hyperoxygenation with a manual resuscitation bag during endotracheal suctioning. Heart Lung. 1993; 22:158–165.

![]() 12. Grap, MJ, et al, Endotracheal suctioning. ventilator versus manual delivery of hyperoxygenation breaths. Am J Crit Care 1996; 5:192–197.

12. Grap, MJ, et al, Endotracheal suctioning. ventilator versus manual delivery of hyperoxygenation breaths. Am J Crit Care 1996; 5:192–197.

![]() 13. Hess, D, Goff, G, The effects of two-hand versus one-hand ventilation on volumes delivered during bag-valve ventilation at various resistances and compliances. Joanna Briggs Institute for Evidence Based Nursing and Midwifery. Tracheal suctioning of adults with an artificial airway. Respir Care 1987; 32:1025–1028.

13. Hess, D, Goff, G, The effects of two-hand versus one-hand ventilation on volumes delivered during bag-valve ventilation at various resistances and compliances. Joanna Briggs Institute for Evidence Based Nursing and Midwifery. Tracheal suctioning of adults with an artificial airway. Respir Care 1987; 32:1025–1028.

![]() 14. Joanna Briggs Institute for Evidence Based Nursing and Midwifery. Tracheal suctioning of adults with an artificial airway. Best Practice. 2000; 4:1–6.

14. Joanna Briggs Institute for Evidence Based Nursing and Midwifery. Tracheal suctioning of adults with an artificial airway. Best Practice. 2000; 4:1–6.

15. Jongerden, IP, et al, Open and closed endotracheal suction systems in mechanically ventilated intensive care patients. a meta-analysis. Crit Care Med 2007; 35:70–260.

![]() 16. Kirimili, B, King, J, Pfaeffle, H. Evaluation of tracheal bronchial suction techniques. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1970; 59:340–344.

16. Kirimili, B, King, J, Pfaeffle, H. Evaluation of tracheal bronchial suction techniques. J Cardiovasc Surg. 1970; 59:340–344.

![]() 17. Kleiber, C, Krutzfield, N, Rose, E. Acute histologic changes in the tracheobronchial tree associated with different suction catheter insertion techniques. Heart Lung. 1988; 17:10–14.

17. Kleiber, C, Krutzfield, N, Rose, E. Acute histologic changes in the tracheobronchial tree associated with different suction catheter insertion techniques. Heart Lung. 1988; 17:10–14.

18. Klockare, M, et al, Comparison between direct humidification and nebulization of the respiratory track at mechanical ventilation. distribution of saline solution studied by gamma camera. J Clin Nurs 2006; 15:301–307.

19. Kubota, Y, et al. Is a straight catheter necessary for selective bronchial suctioning in the adult. Crit Care Med. 1986; 14:755–756.

![]() 20. Kuzenski, B. Effect of negative pressure on tracheobronchial trauma. Nurs Res. 1978; 27:260–263.

20. Kuzenski, B. Effect of negative pressure on tracheobronchial trauma. Nurs Res. 1978; 27:260–263.

21. Lasocki, S, et al, Open and closed-circuit endotracheal suctioning in acute lung injury. efficiency and effects on gas exchange. Anesthesiology 2006; 104:39–47.

![]() 22. McCauley, C, Boller, L. Bradycardiac responses to endotracheal suctioning. Crit Care Med. 1986; 16:1165–1166.

22. McCauley, C, Boller, L. Bradycardiac responses to endotracheal suctioning. Crit Care Med. 1986; 16:1165–1166.

![]() 23. Ogburn-Russell, L. The effect of continuous and intermittent suctioning on the tracheal mucosa of dogs. Heart Lung. 1987; 16:297.

23. Ogburn-Russell, L. The effect of continuous and intermittent suctioning on the tracheal mucosa of dogs. Heart Lung. 1987; 16:297.

![]() 24. Oh, H, Seo, W. A meta-analysis of the effects of various interventions in preventing endotracheal suctioning induced hypoxemia. J Clin Nurs. 2003; 12:912–924.

24. Oh, H, Seo, W. A meta-analysis of the effects of various interventions in preventing endotracheal suctioning induced hypoxemia. J Clin Nurs. 2003; 12:912–924.

![]() 25. Puntillo, KA, et al, Patients’ perceptions and responses to procedural pain. results from the Thunder Project II. Am J Crit Care 2001; 10:238–251.

25. Puntillo, KA, et al, Patients’ perceptions and responses to procedural pain. results from the Thunder Project II. Am J Crit Care 2001; 10:238–251.

26. Rauen, CA, et al, Seven evidence-based practice habits. putting some sacred cows out to pasture. Crit Care Nurse 2008; 28:98–124.

![]() 27. Ridling, DA, Martin, LD, Bratton, SL. Endotracheal suctioning with and without instillation of isotonic sodium chloride solutions in critically ill children. Am J Crit Care. 2003; 12:212–219.

27. Ridling, DA, Martin, LD, Bratton, SL. Endotracheal suctioning with and without instillation of isotonic sodium chloride solutions in critically ill children. Am J Crit Care. 2003; 12:212–219.

![]() 28. Rutula, W, Stiegel, M, Sarubbi, F. A potential infection hazard associated with the use of disposable saline vials. Infect Control. 1984; 5:170–172.

28. Rutula, W, Stiegel, M, Sarubbi, F. A potential infection hazard associated with the use of disposable saline vials. Infect Control. 1984; 5:170–172.

29. St John, RE. Airway and ventilator management. In: Chulay M, Burns S, eds. AACN essentials of critical care nursing. ed 2. New York: McGraw-Hill Publishing; 2006:111–143.

30. St John, RE, Seckel, MA. Airway management. In: Burns SM, ed. AACN protocol for practice: care of mechanically ventilated patients. ed 2. Sudbury, MA: Jones and Bartlett Publishers; 2006:1–57.

31. Subirana, M, et al. Closed tracheal suction systems versus open tracheal systems for mechanically ventilated adult patients. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 4, 2007. [CD004581].

![]() 32. Wynne, R, Botti, M, Parztz, J. Preoxygenation for tracheal suctioning in ventilated adults (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2004. [CD005142].

32. Wynne, R, Botti, M, Parztz, J. Preoxygenation for tracheal suctioning in ventilated adults (protocol). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. (4):2004. [CD005142].

Kerr, M, et al. Effect of endotracheal suctioning on cerebral oxygenation in traumatic brain-injured patients. Crit Care Med. 1999; 27:2776–2781.

Labarca, J, et al. A multistate outbreak of Ralstonia pickettii colonization associated with an intrinsically contaminated respiratory care solution. Clin Infect Dis. 1999; 29:1281–1286.

Paul-Allen, J, Ostrow, C. Survey of nursing practices with closed-system suctioning. Am J Crit Care. 2000; 9:9–19.

Pierce, LN. Management of the mechanically ventilated -patient, ed 2. St Louis: Elsevier, 2007.

Sole, M, Byers, JF, Ludy, JE, et al. A multisite survey of -suctioning techniques and airway management practices. Am J Crit Care. 2002; 11:220–232.