CHAPTER 12. End-of-life decision-making and the nursing profession

L earning objectives

▪ Discuss critically ‘Not For Treatment’ (NFT) directives and ‘Do Not Resuscitate’ (DNR) directives.

▪ Discuss critically the moral criteria that might be used to justify an NFT or DNR directive.

▪ Examine critically the ethical dimensions of NFT and DNR directives.

▪ Discuss critically ways in which NFT and DNR policies and procedures could be improved.

▪ Discuss the notion of ‘medical futility’ and its implications for the profession and practice of nursing.

▪ Explain why medical futility has been abandoned as a decisional criteria in end-of-life decision-making.

▪ Examine critically the criterion ‘quality of life’ and its relevance to end-of-life decision-making.

▪ Discuss critically three senses in which the notion of quality of life might be used.

▪ Explore the possible risks to patients of making faulty quality-of-life judgments.

▪ Define ‘advance directives’ and ‘advance care planning’.

▪ Discuss critically how advance directives work.

▪ Differentiate between advance directives, advance care planning and respecting patient choices (RPC).

▪ Examine critically the risks and benefits of advance directives and advance care planning.

▪ Explore how nurses can make a significant contribution to care and treatment decisions at the end stage of life.

I ntroduction

At the end stages of life there invariably comes a point at which decisions have to be made about whether to start, stop or withdraw life-sustaining treatment. The life-sustaining treatment in this instance can include the use of ‘aggressive’ (invasive) treatments (such as mechanical ventilation/life-support machines, surgery, emergency cardiopulmonary resuscitation, haemodialysis, and chemotherapy), or the use of ‘less aggressive’ (less invasive) treatments (such as the administration of antibiotics, cardiac arrhythmic drugs, blood transfusions, and intravenous and/or nasogastric hydration). Whether involving ‘aggressive’ or ‘non-aggressive’ treatments, decisions have to be made either way (i.e. to treat or not to treat) even when it is ‘obvious’ (or at least highly probable) that their administration will not result in improved clinical outcomes for the patient — for example, the patient will continue to experience ‘grievous bodily deterioration’ (Cantor 2004: 1400) and/or will ultimately die, regardless of the treatment given (Cantor 1995; Chiarella 2006; Morreim 2004; Walter 2004). The question remains, however, of who should decide these things and on what basis?

The question of who ultimately should decide whether to provide, withhold or withdraw life-sustaining treatments at the end stage of life, as well as when, where and how best to decide, are all matters of moral controversy. In clinical contexts, controversies surrounding these issues can also give rise to serious conflict and moral quandary among those involved. Conflict, in this instance, can take the form of health care providers being asked to ‘do everything’ when they believe that a withdrawal of treatment is more appropriate, or, their being asked to ‘do nothing’ (or, at least, to withdraw treatment) when they believe that it should be continued. When ‘unable to agree to either request’, this situation can pose a significant and distressing moral dilemma for decision-makers — and one that is not easily resolved (Fine & Mayo 2003: 744). The dilemmas and distress among decision-makers in these instances can be compounded when there is also disagreement among clinicians about: the nature and stage of a patient’s illness; how responsive a patient’s illness might be to treatment; and whether proposed therapeutic measures are ‘worth it’ if ‘the gain in weeks or months that might reasonably be expected’ by a given therapeutic intervention are significantly outweighed by the loss of quality of life due to the toxic side effects of the treatment (Ashby & Stoffell 1991: 1322; Dawe et al 2002; Mendelson & Jost 2003).

At the forefront of the moral controversies and dilemmas about end-of-life decision-making are the issues of Not For Treatment (NFT) directives, withholding/withdrawing food and fluids (already discussed in the previous chapter) and Do Not Resuscitate (DNR)/Not For Resuscitation (NFR) directives, and the criteria or bases used for justifying these directives such as ‘medical futility’, end-of-life considerations, and advance directives/advance care planning. The practical and moral significance of these issues for attending health care providers (particularly those working in hospitals) is underscored when it is considered that most deaths occur in hospitals and that a significant majority of these deaths occur after a decision has been made — often by someone else — to forgo life-sustaining therapy (e.g. cardiopulmonary resuscitation) (Asch et al 1995; Ayres 1991; Hammes & Rooney 1998; Hardy et al 2007; Loewy & Carlson 1993; Lynn & Teno 1995; Mendelson & Jost 2003). The significance of these issues for the nursing profession, in turn, is underscored by the fact that nurses are often at the forefront of requests either for life support to be withheld or withdrawn or, alternatively, ‘for everything possible to be done’. The ‘rightness’ or ‘wrongness’ of such requests, however, are not always clear-cut and, in contexts where different values, attitudes and beliefs prevail, deciding these things can be extremely challenging (see, e.g. Dawe et al 2002; Heyland 2006). Since these issues have important moral implications for the profession and practice of nursing, some discussion of them here is warranted.

N ot for treatment (NFT) directives

Sometimes, during the course of end-of-life care, an explicit medical directive might be given to the effect that a patient is Not For Treatment (NFT). Sometimes the patient or his or her proxy will agree with (and may even have requested) the NFT decision that has been made, sometimes they will not. It is when there is disagreement about a treatment choice — that is, where a decision is ‘contested’ — that the matter becomes problematic. Here an important question arises, namely: When is it acceptable, if ever, to provide, withdraw or withhold life-sustaining medical treatment at the end stage of life?

T he problem of treatment in ‘medically hopeless’ cases

In the past, decisions about what treatments to provide — when, where and by whom — were made autonomously (some would say paternalistically) by attending doctors. This sometimes led to a situation in which people were being ‘aggressively’ treated even when their cases were deemed ‘medically hopeless’. In other words, people were treated ‘aggressively’ even where it was evident to experienced bystanders that such treatment would not make a significant difference to their health or life expectancy. Sometimes treatment of this nature was imposed without the patient’s knowledge or consent (e.g. those in a so-called ‘persistent vegetative state’), and gave rise to varying degrees of suffering by both patients and their families/friends.

This situation began to change, however, as the public started to become wary of and started to question the wisdom of people being ‘hopelessly resuscitated’. This public questioning saw a number of key cases reaching the public’s attention. Rosemary Tong (1995: 166) explains:

As a result of various factors, the withholding and withdrawing cases that captured the imagination of the public in the 1960s and 1970s were ones in which patients or their surrogates resisted the imposition of unwanted medical treatment. The media portrayed dying patients as routinely falling prey to physicians who, out of fear of subsequent litigation … or out of obedience to some sort of ‘technological imperative’ … insisted on keeping them ‘alive’ irrespective of the quality of their existence.

Tong (1995) suggests that during the 1960s and 1970s, economic resources permitted everything possible to be done. During the 1980s and 1990s, however, it became increasingly evident that neither individuals nor society as a whole could sustain the ‘technological imperative’ to treat regardless of the outcomes. Thus communities in the Western world entered into a new era that was characteristically ‘burdened with new obligations of social justice’ in health care (Tong 1995: 167). Whereas end-of-life issues in the 1960s and 1970s were more concerned with patient autonomy versus medical paternalism, in the 1980s and 1990s they had become chiefly concerned with patient autonomy versus distributive justice (Tong 1995: 166–7). Since the 1990s, however, a key question that has come to dominate bioethical thought is: Are people at the end stages of their lives (or their proxies) morally entitled to request ‘medically inappropriate’ ‘non-beneficial’ and ‘expensive’ (futile) medical treatment? Is it right to refuse such requests? At stake in answering these questions is not just the entitlements of dying individuals but, as Tong concludes (p 167):

the future wellbeing of the health care professional–patient–society relationship — a relationship best understood not in terms of competing rights (though that is an aspect of it), but in terms of intersecting responsibilities.

Disputes about futile or useful treatments at the end stages of life invariably represent ‘disputes about professional, patient and surrogate autonomy, as well as concerns about good communication, informed consent, resource allocation, under-treatment, over-treatment, and paternalism’ (Kopelman 1995: 109). They also represent dispute about ‘how to understand or rank such important values as sustaining a life, providing appropriate treatments, relieving suffering, or being compassionate’ and the bearing these values may have on deciding questions of resource allocation (Kopelman 1995: 111).

W ho decides?

The question of who and how to decide end-of-life treatment options is a difficult one to answer. Choices include:

▪ the medical practitioner (unilateral approach)

▪ the health care team (consensus approach)

▪ the patient or his/her surrogate (unilateral approach)

▪ the health care provider and patient/nominated support person (consensus approach)

▪ society (consensus approach).

While all plausible, none of the above approaches are without difficulties (even in the case of a consensus being reached, this alone is not enough to confer moral authority on the decisions made). For example, while all may entail respect for the autonomy of individuals, they nevertheless risk decisions being made that are arbitrary, biased, capricious, self-interested and based on personal preferences. This is unacceptable (especially in contested cases) since, as Kopelman points out (1995: 117–19):

If one ought to do the morally defensible action in the contested case, then the final appeal cannot be solely preferences of someone or some group. Preference or agreements may be unworthy because they result from prejudice, self-interest or ignorance. In contrast, moral justification requires giving and defending reasons for preferences, and by doing so relying on methodological ideals of clarity, impartiality, consistency and consideration of all relevant information. Other important, albeit fallible, considerations in making moral decisions include legal, social, and religious traditions, stable views about how to understand and rank important values, and a willingness to be sensitive to the feelings, preferences, perceptions and rights of others. The evolution of contested cases often illustrates the pitfalls of failing to take the time and clarify people’s concerns, problems, feelings, beliefs or deeply felt needs or even to consider if people are treating others as they would wish to be treated … Over-treatments may be burdensome to patient and costly to society, yet under-treatments can compromise the rights or dignity of the people seeking help.

In the case of requests being made for ‘everything possible to be done’ some have suggested that there is no obligation to comply with such requests in so-called medically hopeless cases. Jecker and Schneiderman (1995: 160) clarify, however, that ‘saying “no” to futile treatment should not mean saying “no” to caring for the patient’. They conclude (p 160):

[saying ‘no’] should be an occasion for transferring aggressive efforts away from life prolongation toward life enhancement. Ideally, ‘doing everything’ means optimising the potential for a good life, and providing that most important coda to a good life — a ‘good death’.

Decisions about whether or not to initiate or to withhold and/or remove medical treatment on patients deemed ‘medically hopeless’ will rarely be without controversy (sometimes referred to in the bioethics literature as the ‘not starting versus stopping’ debate [see, e.g. Gert et al 1997: 282–3]). Nurses are not immune from the controversies surrounding these decisions, and may even find themselves unwitting participants in them. It is essential, therefore, that nurses are well appraised of the relevant views for and against decisions aimed at limiting or withdrawing the medical treatment of patients deemed (rightly or wrongly) to be ‘medically hopeless’.

D o not resuscitate (DNR) directives1

At some stage during their clinical practice, nurses will be confronted with the difficult moral choice of whether to initiate, participate in decision-making about, or follow a Do Not Resuscitate (DNR) directive (also called Not For Resuscitation (NFR), Do Not Attempt Resuscitation (DNAR), No Code, or Not for CPR). This type of directive is usually given by a doctor to ‘prevent the use of cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) in situations when it is deemed futile or unwanted’ (Sidhu et al 2007: 72). The acronym ‘CPR’ is commonly used to refer to ‘a range of resuscitative efforts, including basic and advanced cardiac life support to reverse a cardiac or pulmonary arrest’ (Sidhu et al 2007: 72). Typically, a DNR directive directs that in the event of a cardiac or pulmonary arrest, neither emergency nor advance life-support measures will be initiated by physicians, nurses or other hospital staff (Martin et al 2007). DNR is thus a form of NFT, and is probably the most common NFT directive operationalised in health care contexts today.

A decision not to resuscitate a person is popularly thought to flow from a medical judgment concerning the irreversible nature of that person’s disease and their probable poor or hopeless prognosis (Haines et al 1990). The validity of this view has, however, been successfully challenged over the past two decades on account of critics showing that the DNR decision is neither a medical decision nor a legal decision per se, but a moral decision since it is based primarily on moral values such as those concerning ‘the meaning, sanctity, and quality of life’ (Yarling & McElmurry 1986: 125).

Up until the late 1990s, few health care organisations had operational DNR policies and guidelines — and those that did had poor compliance rates — a situation that placed patients, staff and hospitals at risk (Collier 1999; De Gendt et al 2007; Giles & Moule 2004; Honan et al 1991; Kerridge et al 1994; Sidhu et al 2007). As a consequence, DNR practices tended to be ‘secret’, characterised by ad hoc, ambiguous, and disparate decision-making and communication, with directives often being given without the patient’s or family’s knowledge or consent. Today, a very different situation exists. Following recommendations made by various government authorities for hospitals to have DNR policies, standardised forms for authorising and communicating DNR directives, and patient information leaflets, as well as the provision of a framework for policy content, many health care institutions in Australia, New Zealand, South Asia, the United Kingdom (UK), Europe and the United States (US) now have transparent, operational and appropriately supported DNR policies, guidelines and practices in place (Carey & Newell 2007; De Gendt et al 2007; Giles & Moule 2004; Hardy et al 2007; Jaing et al 2007; Middlewood et al 2001; Murphy & Price 2007; Sidhu et al 2007). Even so, controversies remain. Moreover, little is known about the quality of DNR processes or the degree to which hospital staff comply with them.

Even though there have been notable improvements in the prevalence and content of DNR (NFR) policies and practices in Australian public hospitals and health care institutions, recent research has found that wide variations nonetheless continue to exist (see, e.g. Hardy et al 2007; Middlewood et al 2001; Sidhu et al 2007). For example, in a 2005 survey of 222 hospitals (of which 157 or 71% responded), it was found that only 54% (n=84) had NFR policies, 39% (n=62) had standardised order forms, and only 3% (n=4) had patient information leaflets (Sidhu et al 2007). Significantly, the researchers also found that hospitals with more than 200 beds were more likely to have NFR policies than those with 60–200 beds (Sidhu et al 2007). Worryingly, almost half (47%) of the policies did not define NFR and few (less than 21%) addressed the issue of dealing with disagreement about NFR decisions. In light of these findings, there is room to suggest, as Younger (1987) did in a classic work published over two decades ago, that DNR directives may be ‘no longer secret, but they are still a problem’ (see, also Hemphill 2007). Thus, while the policy situation has improved, there are still risks (moral, legal and clinical) associated with current DNR practices.

R aising the issues

There is an obvious need to have and to comply with carefully formulated and clearly documented policies and guidelines governing DNR practices. Without such guidelines:

▪ patients’ rights and interests will be at risk of being unjustly violated (e.g. patients could be resuscitated when they do not wish to be, or not resuscitated when they do wish to be)

▪ nurses and other allied health workers will be at risk of having to carry a disproportionate burden of responsibility and possible harm in regard to actually carrying out DNR/CPR directives (although a DNR directive might be given in ‘good faith’ medically speaking, it may nevertheless be vulnerable to criticism and censure — not just on moral grounds but on legal grounds as well, especially if it contravenes a patient’s expressed wishes) (see, e.g. Northridge v Central Sydney Area Health Service [2000]).

The following two cases, those of Mr H and Mr X, illustrate the kinds of problems that can be encountered when DNR policies are inadequate or attending staff fail to uphold best practice standards in relation to DNR/CPR practices. Although these cases occurred several years ago (both in the cultural context of Australia), they nonetheless yield some important lessons for contemporary health care providers and those at the forefront of policy change in this area.

Case 1: Mr H2

Mr H, 60 years old, was admitted to the intensive care unit of a major city hospital with a provisional diagnosis of septicaemia. At the time of admission he was pale, markedly short of breath, and had an auxiliary temperature of 40˚C. Mr H’s past medical history included severe coronary artery disease and a malignant condition. The malignant condition had, however, been successfully treated with chemotherapy, and Mr H was presently in a state of remission. In the light of his provisional diagnosis, a regime of intravenous antibiotics was commenced.

A few hours after Mr H’s admission, the on-coming nursing staff for the afternoon shift gathered for ‘hand-over’. During hand-over, the charge nurse informed the nursing staff present that she had just received a telephone call from Mr H’s physician confirming that the patient was Not For Resuscitation (NFR). As she proceeded to give the afternoon report, a second consulting physician — also involved in Mr H’s medical care — approached the assembled nursing staff and reaffirmed her colleague’s initial NFR directive. The physician then wrote up her clinical assessment of Mr H and made other important documentations on his medical history chart. She did not, however, make any attempt to document the NFR directive which she had just given to the nursing staff. This ‘oversight’ was later dealt with by the nursing staff writing the initials ‘NFR’, in pencil, on the top left-hand corner of Mr H’s nursing care plan, which was held in his medical history chart.

A short time later, a nurse who had been sent to help in the unit became involved in a deep conversation with Mr H. During the conversation, Mr H spontaneously and emphatically exclaimed: ‘Oh, I wish they would operate on me!’ (referring to coronary artery bypass surgery, the opportunity for which he had recently been denied). In response to this the nurse gently asked Mr H whether he had discussed the possibility of bypass surgery with his doctor.

To this Mr H replied quite openly: ‘Sure I have, many times, but they won’t do it because they say there’s only a 50–50 chance of success …’. He went on to say: ‘What can you do? You can’t hit them over the head with a bottle and make them do it, can you?’. The nurse inquired further: ‘So even though you’d only have a 50–50 chance — you’d still want this coronary bypass surgery?’

Mr H replied, sombrely:

Oh, yes. I’d do anything to buy some time. You see, my wife’s very ill at home. She has cancer which can’t be operated on. She’s always been totally dependent on me — even more so since she’s been sick. She doesn’t have very long to live, and all I want is to live long enough for her, because she’s so afraid of being left alone. We can’t do much, and we each stay in separate rooms at home. But at least we’re reasonably independent and together. I can bring her a cup of tea when she wants it and things like that. I don’t care about me, but I want to live long enough for her … she’s so afraid of being left alone …

Smiling, Mr H concluded: ‘It’s such a comfort knowing that you and the doctors are doing all that you can for me here …’

Realising that Mr H clearly had no knowledge of the NFR directive against him, the nurse went immediately to discuss the matter with the other nurses, who were still in the nurses’ bay, having not yet moved to care for their respective patients. There, she discreetly asked whether Mr H or his relatives had been involved in making the NFR decision. To this question one nurse replied: ‘Oh! Surely that’s silly to include the patient or the relatives …’ and, almost simultaneously, another nurse replied: ‘No. We don’t do that in this hospital. It’s the doctors’ decision, and we’re obliged to obey their orders …’.

The nurse caring for Mr H then attempted to point out that her patient had indicated that he very definitely wished to risk the odds of active resuscitation. She then asked further whether the doctors were aware of Mr H’s desires. To this, the nurse in charge replied sternly: ‘Of course the doctors know! It’s their decision, and it’s the policy of this hospital to follow such orders.’

As the afternoon shift progressed, Mr H experienced a number of bradycardiac episodes, with the cardiac monitor showing his heart rate dropping to as low as 34 in some instances. The arrhythmia could have been treated relatively easily by the attending nurse administering a prescribed bolus dose of intravenous atropine. When the nurse caring for Mr H went to have the drug checked with the nurse in charge (as was required by unit policy), she was told: ‘You don’t need to worry about that, he’s NFR …’ Despite the attending nurse’s protests, the nurse in charge still refused to check the atropine. Fortunately, during the time of intense debate between the attending nurse and the nurse in charge, Mr H’s cardiac rhythm reverted spontaneously to a rate of between 80 and 90 beats per minute. Mr H had several more bradycardiac episodes throughout the shift, but each time spontaneously reverted to a safe rate of 80–90 beats per minute.

A few days later, Mr H’s temperature dropped significantly to within normal limits. He stated that he felt better and was looking forward to going home. His blood cultures came back negative (negating his provisional diagnosis of septicaemia), his heart rate was more stable, and his breathing continued to improve. Despite this, however, the NFR directive was not rescinded. Mr H’s condition dramatically improved even further one afternoon when he was given a stat dose of intravenous lasix (a diuretic). Following this, it was decided that the presenting medical condition had not, in fact, been septicaemia but pulmonary congestion (secondary to his heart disease) and pneumonia.

Just six days after his initial admission into the intensive care unit, Mr H was judged sufficiently well recovered to be discharged home. He left, happy, thanking the nursing staff for all that they had done and expressing his eagerness to leave and be reunited with his dying wife.

Rightly troubled by the incident, the nurse made an appointment to discuss the matter with the then director of nursing. During the conversation, the nurse indicated that in future she would override any nurse in charge and would contact the prescribing doctor to clarify an existing NFR directive. To this the director of nursing replied:

Well, of course, if you had contacted the doctors involved in this case, you would probably have found that they wouldn’t be very forthcoming anyway. In fact, they would probably have told you it was not your concern. You will find here that it is really the doctors’ decision in cases like these, since it is they who have the contract with the patient, not the nurses …

Case 2: Mr X

The second case to be considered here is taken from the Victorian State Government Social Development Committee’s Inquiry into options for dying with dignity: second and final report (Social Development Committee 1987). It involves the case of Mr X, who was also cared for in a major city hospital.

Mr X, 78 years old, was admitted to hospital with a provisional diagnosis of ‘Transitional Cell Carcinoma, with metastatic spread to the lungs, liver and spinal cord and brain’ (Social Development Committee 1987: 111). On admission, Mr X was observed to be lethargic, disorientated and suffering a greater degree of pain than on previous admissions. He had lost weight and admitted to having lost his appetite. The nurse relating the case stated that (p 112):

it was apparent to me that Mr X’s disease process had insidiously created a decline in his overall wellbeing, to a point where it had now affected his quality of life.

On Friday morning, upon consultation with the ward’s resident medical officer, it was stated that Mr X ‘had now reached the terminal stage of his illness’ and that, apart from keeping him comfortable, nothing more could be done for him, medically speaking. On Friday evening, Mr X’s deteriorating condition was discussed with his relatives. It was reported that (p 112):

His relatives were distressed over the deterioration they had observed over the past few weeks in Mr X’s condition and wellbeing. At this time they emphatically expressed their wish that should Mr X arrest while in hospital, they in no way wanted an emergency procedure of resuscitation performed on him, and wished for him to be allowed to die peacefully with a degree of dignity assured.

Later that same evening, Mr X himself requested (via the hospital chaplain) that ‘should he die that evening he had no wish to be actively resuscitated and would prefer to die peacefully’ (p 113).

Mr X’s condition continued to deteriorate. On Saturday morning, the nurse in charge called the covering resident medical officer to examine Mr X medically so that it could be formally established that Mr X ‘would not be for resuscitation’ in the event of his suffering a cardiac arrest. The Social Development Committee (p 113) further reports:

The doctor examined Mr X, and agreed that he should not be for cardiopulmonary resuscitation. However, he also stated that he could not instigate that decision until Monday morning, until he had consulted the Registrar and Consultants of the unit, thereby allowing his decision to be reached as a team decision. On this note, Mr X was still for resuscitation should he arrest, in spite of his and his relatives’ wish to allow him to die with peace and dignity.

Over the next 24-hours, Mr X’s condition declined even further, and at 5 pm on Sunday, in the presence of his relatives, he suffered a cardiac arrest. As the covering resident medical officer had requested that Mr X should still be resuscitated — at least until the matter could be discussed with the unit team — an immediate resuscitation code was called. Full resuscitation procedures were instigated and continued for approximately 20 minutes. No positive outcome was achieved, however, and Mr X was declared clinically dead. Understandably, Mr X’s relatives were very distraught about the incident and ‘even more so’, as the report goes on to quote, ‘about the fact that Mr X had been resuscitated both against his and their wishes’ (p 113).

The issues raised by these and other case scenarios can be broadly categorised under three general headings:

1. problems concerning DNR decision-making criteria, guidelines and procedures

2. problems concerning the documentation and communication of DNR directives

3. problems concerning the implementation of DNR directives.

P roblems concerning DNR decision-making criteria, guidelines and procedures

Criteria and guidelines used

Despite the existence of DNR policies and guidelines, different doctors and nurses may nevertheless appeal to different criteria (to be distinguished here from procedures) for making DNR/CPR decisions. For example, some doctors and nurses might appeal to end-of-life criteria (to be discussed later in this chapter), while others might appeal to sanctity-of-life criteria when making DNR/CPR decisions (discussed in the previous chapters on abortion and euthanasia). Although DNR/CPR decisions based on either of these criteria might well be in accordance with a patient’s preferences, they might equally be in contravention of them. There have been some notable instances of this. For example, in one case in which end-of-life criteria were applied, a previously fit 90-year-old man who required admission to hospital for multiple medical problems was not resuscitated following a cardiac arrest. The decision not to resuscitate him was made by attending medical staff even though both the patient and his wife had clearly indicated that they wished ‘everything possible’ to be done to try and preserve his life — including cardiopulmonary resuscitation in the event of a cardiac arrest (Hastings Center Report 1982b: 27–8). In contradistinction to this case, in another case this time involving an appeal to sanctity-of-life criteria, a 70-year-old woman ‘was resuscitated over 70 times within a few days’ (Annas, in Bandman & Bandman 1985: 236). In another similar case, a patient was resuscitated 52 times before ‘family members literally threw themselves across the crash cart to prevent the team from reaching the patient’ for the 53rd time (Dolan 1988: 47). Although these cases occurred some time ago, they nonetheless serve to provide important reminders of the moral risks involved when different people use different criteria to inform their DNR/NFR decisions and practice.

Another troubling practice is that of hospital staff deeming patients to be DNR on the basis of a DNR decision made during a previous hospital admission. For example, if a patient is made DNR during an admission to hospital in March, is discharged, but comes back into hospital in April, the patient is made DNR again on the basis of the March hospital admission decision. Although the degree to which this practice occurs is not known, Sidhu et al’s (2007) study of NFR policies and practices in Australian public hospitals (cited earlier) found that, in the case of patients who had an NFR order from a previous admission, only 34% of policies of the hospitals surveyed indicated that ‘a new order was required’ (p 73). In other words, 66% of respondent hospitals left open the possibility of patients being deemed NFR on the basis of a previous hospital admission. In the case of patients being admitted from another institution with a standing NFR order, only 3% of the policies surveyed contained provisions for dealing with this situation. The rationale behind this is not entirely clear. What is clear, however, is that such a practice is in contravention of acceptable standards of safe and quality care and should be abandoned.

Equally disturbing is the over-reliance on age as a decisional criterion when making DNR/CPR decisions. Many residential care homes for the aged, for example, have a universal policy of not resuscitating their residents in the event of either a cardiac or respiratory arrest. Persons entering these homes are asked whether they wish to be cremated and where they wish to be buried, but are not always asked whether they wish to be resuscitated if and when they should cardiac arrest. Likewise palliative care units/hospices, where NFR directives are taken as ‘implicit’ and assumed — without discussion or consent — to come into effect upon admission. For example, in an audit of Queensland hospitals and institutions caring for people who are dying, Hardy et al (2007) found that NFR directives were documented in only 55% of cases overall. The researchers noted, however, that there was a marked discrepancy in documentation practices found in hospitals, and hospices and nursing homes: whereas hospitals documented NFR orders ‘on most occasions’, in hospice and nursing home contexts, NFR orders were ‘rarely documented’ (Hardy et al 2007: 318). What is disturbing about these findings is the apparent disregard for the choices of the institutionalised elderly and the dying that they demonstrate. In the case of the elderly, they also demonstrate a questionable reliance on what research has long shown to be an unreliable and invalid decisional criterion — notably age (see in particular Fader et al 1989; Sage et al 1987).

As a point of interest, a British study, involving 100 inpatients (mean age 81.5 years) in an acute hospital elderly care unit, found that 73% of those patients questioned indicated that they would want CPR in the event of a cardiac arrest; this compared with 18% of those questioned indicating that they would not want CPR in the event of a cardiac arrest, and 9% who indicating that they were unsure (Mead & Turnbull 1995). However, in another North American study (involving 287 elderly people with a mean age of 77 years), a team of researchers found that, in contradiction to most other studies suggesting that a majority of elderly patients would want to undergo CPR in the event of a cardiac arrest, once respondents were informed about the probabilities of survival following CPR, their preference for CPR declined significantly (i.e. almost halved) (Murphy et al 1994). These and related studies are nevertheless unanimous in their conclusions: elderly people are capable of being — and should be — consulted about their CPR status in health care contexts — a conclusion that is supported by other studies (see, e.g. Cherniack 2002; Heyland et al 2006; Phillips & Woodward 1999).

Finally, how to resolve disagreements about what criteria should be used to inform DNR decisions — and how to resolve disagreement generally about whether to prescribe DNR or reverse a DNR directive once made — are also not addressed in guidelines. In the Sidhu et al (2007) study, for example, it was found that 58% of policies neither anticipated nor outlined procedures for reversing DNR/NFR orders that had been given.

The exclusion of patients from decision-making

Despite the widespread acceptance of the principle of patient autonomy and informed consent — and acknowledging that some patients do not want to and may also be unable to participate in decision-making about DNR (Heyland et al 2006; Tonelli 2005) — some doctors and nurses nonetheless genuinely believe that patients or their relatives who otherwise want to be involved should not be included in the process of making DNR/CPR decisions (Cherniack 2002; Loewy 1991; Phillips & Woodward 1999; Perry et al 1986; Schade & Muslin 1989). For example, in one Australian study it was found that in 30% of cases (n=88) reviewed, a DNR order had been authorised by the treating doctor alone (compared with just 5% in another comparative overseas study); the study also found that of the 88 DNR orders given, only 24 patients had been directly involved in discussions about the documented CPR order, 38 cases were discussed with the patient’s family only, and in 26 cases there was no evidence of any discussion taking place with either the patient or family about the DNR directive that had been given (Middlewood et al 2001). In another Australian study, researchers found that despite advance directives and ‘living wills’ being effective in end-of-life decision-making, 62% of hospital DNR policies surveyed did not address advance directives or living wills (Sidhu et al 2007).

Responding to the case of the 90-year-old man (mentioned above), Carson (1982: 28) argued that the admitting hospital in that case had an official policy which effectively took the position ‘that entering patients should not be bothered with the details of resuscitation policy but should assume that they will be well cared for and coded if necessary’. Commenting on the same case, Siegler (1982: 29) went even further arguing that where a physician knows (‘within limits of uncertainty that characterise all medical knowledge’) that CPR would be of no possible benefit to the patient, it should not be initiated — regardless of a patient’s preferences to the contrary.

Excluding patients or their proxies from participating in DNR/CPR decisions can, however, result in unnecessary suffering for the patient (if he/she survives) and their loved ones. For example, when informed that no attempt had been made to resuscitate her husband, the wife of the 90-year-old man (referred to above) reportedly stated that the decision was ‘against her wishes’ and that:

Doing everything […] is the difference between life and death. The doctor was playing God when he decided he should not try to save my husband. You’re not playing God when you’ve tried everything and exhausted all methods. All I wanted was for them to try. My husband knew how to love and be loved. That was his quality of life. That suited him and it suited me.

(Hastings Center Report 1982b: 28)

Many health care professionals believe — rightly or wrongly — that patients should not be ‘burdened’ with having to decide whether they should be resuscitated in the event of a cardiac arrest — particularly if the patient’s condition is ‘medically hopeless’ and any further treatment — including CPR — would be ‘futile’ (Cherniack 2002; Lo 1991; Loewy 1991; Scofield 1991; Haines et al 1990; Tomlinson & Brody 1990). Some go even further to suggest that, in some instances, health care professionals have no obligation to engage the patient in decision-making — pointing out that, ‘under certain circumstances, arousing a dying patient to inform them of their imminent demise runs counter to the principle of beneficence in health care’ (Tonelli 2005: 637). This stance has resulted in patients (or their proxies) sometimes not being consulted about a DNR directive even though institutional policy has required that their consent be obtained and even though research has consistently shown that a majority of patients and their proxies want to be involved in decision-making concerning DNR/CPR directives (Cherniack 2002; Mead & Turnbull 1995; Honan et al 1991). An important lesson here, as Sidhu et al (2007: 75) warn, ‘the presence of a policy does not guarantee that it will be followed’.

Misinterpretation of directives and questionable outcomes

Another difficulty associated with current DNR policies and guidelines is that they are vulnerable to being misinterpreted which, in turn, can result in the under-treatment and substandard care of patients (Johns 1996). For example, in the case of Mr H, described at the beginning of this discussion, the DNR directive was interpreted, controversially, as also including the non-treatment of a potentially fatal but relatively easily treatable cardiac arrhythmia. This interpretation is even more troubling when it is considered that the patient was, after all, being cared for in an intensive care unit, where the imperative is normally to treat not to withhold treatment from patients presenting with treatable life-threatening conditions.

Another disturbing example of the way in which a DNR directive can be misinterpreted can be found in the case of a dying patient who had pulmonary congestion and pneumonia, and, associated with these two conditions, copious mucus production. In this case, the nurses (mis)interpreted the DNR directive to include withholding oropharyngeal/nasopharyngeal suctioning. As a result, the patient was left, quite literally, to drown in his own secretions — until another nurse detected the error and took immediate action to correct the other nurses’ misinterpretation of the directive. The lesson to be learned from this case — and others like it — is that ‘No Code’ does not mean ‘no care’ (Heyland et al 2006; Lo 1991).

P roblems concerning the documentation and communication of DNR directives

A second issue of concern in the DNR debate involves the use of disparate means by which DNR directives are documented and communicated to members of the health care team (see De Gendt et al 2007; Giles & Moule 2004).

In the past, DNR directives were communicated using the following questionable processes:

DNR directives being given verbally only (i.e. they were not formally documented in the patient’s medical or nursing notes). This practice came about largely because doctors were ‘loathe to indicate in written notes in patient records that a patient [was] not for resuscitation’ (Social Development Committee 1987: 108).

▪ DNR directives being ‘confirmed’ by sticking coloured dots (usually black ones) or scribbling an asterisk either on the patient’s medical history chart and/or by the patient’s name on the ward’s bed allocation board. As a point of interest, in 1988 the Association of Medical Directors of Victorian Hospitals recommended to the Victorian Hospital Association that ‘a round white sticker with “sky” blue border and an oblique “sky” blue stripe be adopted by hospitals to denote Not For Resuscitation’. They advised that the sticker should be ‘placed on the front of the patient record, on the bed card and on the patient’s wristband’ ( Victorian Hospital Association Report 1988: 3).

▪ DNR directives being ‘confirmed’ by pencilling the initials ‘DNR’ or ‘NFR’ or some other equivalent in an inconspicuous place on the patient’s medical history or nursing care plan, or both.

▪ DNR directives being written euphemistically as ‘routine nursing care only’, or ‘cares for comfort only’ (Cushing 1981: 24).

While once commonly accepted throughout institutional health care settings, these modes of communicating DNR directives were (and are) highly questionable. For instance, as with any verbal directives, verbal DNR directives are vulnerable to being misinterpreted. More seriously, a person who originally gave a verbal DNR directive could later deny that any such directive was given at all. An instructive example of how very serious errors can be made on account of verbal DNR directives being given and, equally instructive, how easily an attending doctor can deny ever having given a verbal DNR directive is provided below.

The case in question involved a patient, identified as Mrs M, who suffered a cardiac arrest while being cared for in an intensive care unit. A medical student covering the unit was called. After initiating CPR he is alleged to have stopped, saying: ‘What am I doing? She’s a no-code,’ and then stopped performing cardiac massage (Adams 1984: 54). The case was eventually brought before a grand jury after a nurse anonymously informed Mrs M’s daughter that ‘her mother had died “unnecessarily” because “a no-code was sent out” ’ (p 55). As a point of interest, the medical student testified that he never made the comment. When the medical student was later asked in an informal situation why he treated Mrs M as a ‘no-code’, he replied that the directive to do so had been given to him verbally by a cardiologist (p 55).

It is sometimes mistakenly assumed that a verbal DNR directive will ‘convey the directive without attaching any legal liability’ (Cushing 1981: 27). Cushing warns, however, that (p 27):

while many hospitals allow no code orders to be ‘unofficial’, it is difficult to justify a continuation of this practice. Once the medical decision has been made, the order should be written as any other medical directive.

In addition to verbal directives, there have been other questionable methods used for communicating DNR directives, such as the use of coloured dots, asterisks and pencilled initials and abbreviations. Like verbal directives, however, coloured dots, asterisks and pencilled initials and abbreviations are ‘high risk’ practices that could result in serious errors being made. It seems quite inconceivable that important and competent medical decisions concerning the life and death of a human being were once reduced to something so careless as a simple black dot, an asterisk, or a set of pencilled abbreviations. It is also inconceivable that competent health professionals once relied so readily on these crude symbols for determining whether or not the interventions needed to aid a seriously ill or dying patient should, in fact, be initiated. The additional dangers of dots were (and are), of course, that they could be bought and placed on charts by almost anybody; they could also become dislodged, stick to the wrong chart, or be placed by the wrong person’s name on the bed allocation board, and so on (Adams 1984; Macklin 1993: 34–6).

The use of abbreviations such as ‘DNR’, ‘NFR’, ‘DNAR’ and variations thereof, is also problematic. In one case, for example, a nurse informed me that a doctor had once ordered her to write the initials ‘NFR’ on a patient’s chart. When she queried this directive, she was politely told: ‘Don’t worry. If there are any problems, we’ll just say it means “Not For Referral” …’ In another case, the initials ‘NFR’ were written on a patient’s nursing care plan, which was left hanging on the end of his bed. During visiting hours, a family member visiting the patient took the liberty of examining the nursing care plan and noticed the initials ‘NFR’ on it. She asked a passing nurse what the letters meant. To this question the nurse replied: ‘Oh, don’t worry about that. It just means “Nice Fellow Really …” ’

In yet another case, a dietician writing in a patient’s integrated case notes (i.e. where all members of the health care team — doctors, nurses, and other allied carers — write up their notes) wrote the initials ‘NFR’ meaning ‘Not For Referral’. Understandably, the dietician was very distressed when the significance of what she had written was pointed out to her.

A last concern to be considered here is the practice of ordering ‘nursing care only’ or ‘cares for comfort only’ when it is considered that nothing more can be done medically for the patient. The professional — not to mention the moral — acceptability of using ‘nursing care only’ as a euphemism for withdrawing life-saving medical treatment warrants questioning, however. For one thing, in situations where all means have not, in fact, been exhausted, there is always room to question whether CPR (or any other life-supporting measure, for that matter) should, in fact, be rightfully withheld from a patient. On this point it is worthwhile to consider Veatch’s helpful comments. In his book Death, dying and the biological revolution, Veatch writes (1977a: 8):

The question should never be, ‘When should we stop treating this patient?’ as if the patient were an object to be repaired or discarded. Rather the moral question must be, ‘When, if ever, should it be morally and/or legally possible for the patient to decide to refuse medical treatment even if that may mean that dying will no longer be prolonged?’

P roblems concerning the implementation of DNR directives

Even when all proper processes have been followed, a nurse might still be left in a quandary about whether to uphold a given DNR directive and may, in practice, experience difficulties implementing a directive even though ‘medically indicated’ and lawfully prescribed (Dawe et al 2002; De Gendt et al 2007; Giles & Moule 2004; Sidhu et al 2007).

Most nurses probably have no difficulty carrying out DNR directives — indeed, in some instances, they may even be largely responsible for encouraging doctors to prescribe them. Some nurses, however, may suffer significant hardships on account of various institutional demands to follow established DNR policies and guidelines.

For instance, there have been a small number of cases in which nurses have been dismissed from their places of employment because of deciding not to initiate resuscitation on a patient even though no DNR directive was in place. In one noted English case, for example, a registered nurse ‘who chose to let an elderly man die rather than call in a resuscitation team’ was dismissed for gross misconduct ( Nursing Times 1983a: 20; see also Johnstone 1994: 258–9). The fact that the man had lung cancer, was 78 years old and essentially died of ‘natural causes’ was not deemed relevant to the case (Buchanan 1983; Regan 1983). In another case, this time in Australia, a registered nurse was likewise dismissed from her job and also faced disciplinary action for allegedly ‘disobeying a written directive to continue medical treatment’ on a seriously ill elderly woman and, on her own volition, deciding that the patient should be ‘classified as not for resuscitation’ (Collier 1999). Although the patient’s physician is reported to have later agreed that a ‘not for resuscitation order’ would have been given, hospital authorities apparently took the position that the dismissal was justified on the grounds that the nurse had contravened hospital policies (Collier 1999).

The issue of implementing DNR directives is of particular concern to nurses since, quite simply, they are the ones often left with the ultimate decision of whether or not to initiate CPR in an arrest situation. They are thus also invariably left with the burden of having to accept the responsibility for the consequences of both their actions and their omissions in cardiac and respiratory arrest situations.

I mproving DNR practices

It is acknowledged here that DNR practices have improved significantly over the past two decades. Nevertheless, as the research referred to in this discussion has suggested, there are still areas that stand in need of improvement. To this end the following recommendations are made:

1. There needs to be a recognition that DNR decisions have a profound moral dimension, and are not just medical, nursing or legal in nature, and because of this must be made by appealing to sound moral criteria and standards as well as to relevant clinical information.

2. Any DNR decision made ought to reflect the patient’s [or the patient’s nominated carers] informed choice (given informed choice in its most stringent sense here).

3. DNR decisions/directives should be clearly written on patients’ medical and nursing charts, and should include all the relevant information upon which the decisions have been based (including descriptions of the patients’ statements relevant to their request that life-saving measures be withheld); a standardised ‘DNR authorisation’ or a ‘Limitation of Medical Treatment’ form should also be signed.

4. Mechanisms must be established to ensure the correct interpretation of non-treatment directives.

5. Once a DNR decision has been made, it should be reviewed and reaffirmed in writing at intervals which are appropriate to the patient’s changing condition.

6. A DNR directive should be able to be revoked at ‘any time at the request of the competent patient, or in the case of the incompetent patient, by the cited next-of-kin or legal representative’, or as is morally appropriate (Clinical Ethics Committee 1984; Sidhu et al 2007).

7. A DNR decision should be carried out only by those who have freely, and possessing the necessary information, agreed to carry out such directives. Where nurses or doctors have genuine conscientious objection to following a DNR directive, morally they ought to be permitted to abstain from being actively involved in caring for the patient in question.

By incorporating these and other similar considerations in DNR policies and guidelines, nurses and doctors can rest assured that they truly have done all that is possible to ensure that patients’ rights and interests have been properly respected in life-threatening situations, and that they have not overstepped their authority as health care providers. Members of the community at large can also rest assured that their assumptions about being well cared for upon coming into hospital or other related health care agencies are not misplaced, and that they can indeed trust and rely on those people who will most probably care for them during those delicate, life-threatening moments which are all too often characterised by intense personal need and human vulnerability.

M edical futility

One criterion that is commonly used to justify non-treatment (e.g. NFT/DNR) decisions is that of ‘medical futility’. The concept of ‘medical futility’ (from the Latin futtilis, meaning pouring out easily, worthless) is generally used to refer to medical treatment that ‘fails to achieve the goals of medicine’ in that it offers no discernible benefit to the patient (i.e. it fails to overcome the patient’s medical problem, or results in the patient surviving, but only to lead a ‘useless life’) (Nelson 2003; Jecker 1993).

The notion of medical futility first began being debated in the mid-1980s and was advanced largely in an attempt to convince the public of the need to establish a public policy that would enable treating doctors to ‘use their clinical judgment or epidemiological skills to determine whether a particular treatment would be futile in a particular clinical situation’ (Helft et al 2000: 293; see also Taylor & Lantos 1995). Underpinning this movement was the idea that:

once such a determination had been made [that a particular treatment was futile], the physician should be allowed to withhold or withdraw the treatment, even over the objections of a competent patient.

(Helft et al 2000: 293)

The notion of medical futility proved to be extremely controversial, however, and sparked a debate of unprecedented vehemence in the medical literature (Nelson 2003; Helft et al 2000). Interestingly, this debate peaked in 1995 and then waned, largely because a consensus on the matter could not be achieved: for every thoughtful definition of ‘medical futility’ that was put forward, critics successfully raised counter-objections, pointing out exceptions that made broad acceptance of the notion and its operationalisation impossible (Nelson 2003; Helft et al 2000).

Linchpin to the objections raised against the notion of medical futility — including both its objective biophysiological (quantitative) and subjective end-of-life (qualitative) elements — were arguments that convincingly showed judgments about medical futility primarily involved ‘moral judgments about right and good care’, rather than clinical judgments about what was ‘medically indicated’ and therefore ‘medically warranted’. Even when medical (clinical) judgments were based on rigorous clinical and epidemiological data, it was acknowledged by proponents of the medical futility movement that such data ‘could not be used [reliably] to determine the level of probability that would justify calling a treatment futile’ since such data tended to represent groups not individuals (Helft et al 2000: 294). These data and related systems of prognostication that were devised during this period could not be used for another reason, namely, they failed to take into account the ‘existential’ goals that various treatments might be capable of achieving, such as enabling a patient to remain alive ‘to see a loved one again’ (Helft et al 2000: 294). Finally, it was recognised that while doctors ‘may be more qualified than patients to make technical judgments about medical treatment, they have no particular expertise in making decisions about such subjective matters as futility’ or the subjective values, views, and goals of patients on which judgments of futility were heavily reliant (Helft et al 2000: 294).

From the mid-1990s to around 2003, with the notable exception of the texts by Zucker and Zucker (1997) and Rubin (1998), there was relatively little published on the subject of medical futility. For example, a search of the Cumulative Index to Nursing and Allied Health Literature (CINAHL) database in 1995 located 134 articles on medical futility (Helft et al 2000); in contrast, in October 2003, a ProQuest search of multiple databases for the preceding 12-month period located only 21 articles on the topic and, of these, only five carried the term ‘futility’ in the title. A follow-up search of the ProQuest multiple databases for the period 2004–2007, however, located 100 articles on the topic, of which 24 contained the term ‘futility’ and seemed to be signalling a resurgence of interest in the topic. Regardless of whether there is a decline in or a resurgence of interest in the topic of medical futility, the question of how best to decide treatment options that are of limited benefit to patients at the end stage of life remains problematic. Furthermore, even though debate on the notion of medical futility has, languished, there is much to suggest that local definitions of medical futility are nevertheless very much in use and indeed are operationalised in hospitals every day to inform (non)treatment decisions (as has been shown by the discussion above, this is especially evident in the case of NFT and DNR directives). A notable example of this can be found in the controversial case of the St Francis Medical Center, a 220-bed tertiary Catholic hospital located in suburban Honolulu, which in 2003 developed and operationalised a specific and targeted ‘medical futility policy’ — reprinted in full in Tan et al (2003). At the time, this initiative was viewed with some concern by observers external to the organisation who feared that other hospitals would follow suit (see, e.g. Hamel & Panicola 2003).

Q uality of life

A key decisional criterion commonly appealed to when making decisions about care and treatment for patients at the end stages of life is that of quality of life. End-of-life considerations are deemed to be particularly important in situations where a patient’s life ‘might be saved only to be lived out in severely impaired conditions’ (Walter 2004: 1388). In such situations, end-of-life considerations might be used, albeit controversially, to justify withholding or withdrawing life-sustaining medical treatment from a particular patient.

Despite being frequently appealed to when making treatment decisions, the end-of-life criterion is not without controversy. One reason for this is that quality of life is difficult to define and can be used to refer to different though equally valid (subjective) realities. In short, as Welch-McCaffrey (1985: 151) points out: ‘Quality of life is not a term that has unequivocal meaning nor is it unambiguously determinable in any given case.’

D efining quality of life

Defining quality of life can be a lesson in linguistic humility. One reason for this is that what is at issue here is not just defining ‘ quality of life’, but ‘ life’ itself. In the case of the term ‘life’ (from Old Norse, liֿf meaning body), this can be used to refer to two different realities, namely the:

(1) vital or metabolic processes that could be called human biological life; or (2) human personal life that includes biological life but goes beyond it to include other distinctively human capacities, for example, the capacity to choose and to think.

(Walter 2004: 1389)

Likewise with the term ‘quality’ (from Latin quaֿlitaֿs, meaning state, nature), which can refer to several different realities, including: a formal state of excellence; the attributes or properties of either a personal or biological life; the minimum attributes necessary for a personal life (e.g. the capacity or potential capacity to have human relationships/to pursue human purposes/to live life independently); the value (worth) of life itself (Walter 2004; Kuhse 1987). Each of these realities, in turn, can be variously interpreted, and their interpretations variously interpreted, and so on ad infinitum, further demonstrating the complexities involved in trying to devise an agreed operational definition of the criterion.

To date, no consensus has been reached on how ‘quality of life’ should be defined or interpreted. There is, however broad agreement that the criterion essentially defies precise definition, or at least a definition which could be regarded as being universally acceptable. Nevertheless, as Downie and Calman (1987: 190) argue:

Most … would agree that quality of life relates to the individual person, that it is best perceived by that person, that conceptions of it change with time, and that it must be related to all aspects of life.

D ifferent conceptions of quality of life

When appealing to end-of-life considerations in health care contexts it is important for health care professionals (including nurses) to recognise that ‘quality of life’ can mean very different things to different people. For example, a class of students undertaking a post-registration Bachelor of Nursing course at RMIT University were once asked for their views on what they regarded as constituting a ‘quality of life’. In response to this question, they identified the following (differing) characteristics:

▪ enjoyment and being happy, further defined as:

• feeling contented

• having no worries

• being stress-free

• feeling fulfilled

▪ being healthy (and not having to suffer in any way)

▪ having freedom and independence (being self-determining)

▪ being able to function effectively

▪ actual achievement and/or being able to achieve important goals

▪ having the love of family and friends.

The fact that these students held differing views about what constitutes quality of life is not, in itself, problematic. However, were these students to impose their personal views on their patients and/or to use their personal views to influence care and treatment decisions involving patients with life-threatening illnesses, this would be a different matter. Of particular concern would be the risks that such an imposition of views could pose to patients, especially if they were to influence treatment decisions that could be shown later not to have accorded with the patient’s end-of-life views. To illustrate the kind of risks involved, consider the following.

In a study on quality of life following spinal cord injury (SCI), a team of researchers found that emergency health care providers’ (including nurses’) attitudes about quality of life following SCI were substantially more negative than the attitudes expressed by those who had actually sustained such an injury. For instance, whereas only 18% of emergency health care workers ‘imagined they would be glad to be alive with a severe SCI’, a substantial 92% of those who had a true SCI were glad to be alive (Gerhart et al 1994). And whereas only 17% of emergency health care workers ‘anticipated an average or better quality of life’ following an imagined SCI, 86% of those who had a true SCI had an average or better quality of life (Gerhart et al 1994; see also Hammell’s 2007 meta-analysis of qualitative research on quality of life after SCI).

Health care providers (nurses among them) sometimes assume that people who suffer devastating injuries (or illnesses) have — or will have — a poor quality of life. Further, this belief is sometimes translated into the judgment that ‘those who cannot lead normal lives would be better off dead’ (Gerhart et al 1994, citing Dunnum 1990). Not infrequently, these kinds of judgments influence decisions about whether or not to treat patients deemed ‘medically hopeless’ and who, if treated, could at best live only an ‘impaired life’. It is important to note, however, those who provide health care and those who receive it may not always share the same view about the conditions under which a quality of life is possible (Hammell 2007).

End-of-life judgments can have a significant bearing on quality (and quantity) of care/treatment decisions. The views and attitudes of health care providers may not only significantly affect the care they provide, but may also ‘influence patients and families struggling with critical treatment decisions’ (Gerhart et al 1994: 807). It is therefore vital that health care providers exercise great care when making end-of-life judgments, and act in a morally responsible way when using these judgments to inform clinical decisions. Anything less could result in morally undesirable consequences. For example, a prejudicial judgment about an SCI patient’s quality of life could result in needed care and treatment being withheld or withdrawn prematurely, and the patient dying prematurely as a consequence.

U sing end-of-life considerations to inform treatment choices

As the discussion thus far has shown, quality of life as a decisional criterion can only be interpreted subjectively and, at the end of the day, can mean quite different things to different people. This finding is important since, among other things, it warns that using quality of life as a decisional criterion when making end-of-life treatment choices is not without risks (e.g. what might be an appropriate non-treatment decision for one person, might be quite inappropriate and even wrong for another). It also warns that members of the health care team involved in making end-of-life treatment decisions need to take great care to ensure that what they consider to be ‘quality of life’ is congruent with what their patients consider to be ‘quality of life’ and, further, that such considerations are in fact relevant to deciding the care and treatment options in the situation at hand.

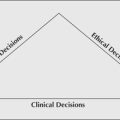

Although quality of life defies precise definition, there are nevertheless three different senses in which it can be used when deciding care and treatment options: descriptively, evaluatively and/or prescriptively (that is, morally) (Walter 2004; Morreim 2004; Reich 1978).

Reich (1978: 830) explains that where the term quality of life is used as a descriptive statement, an observation is being made merely about the properties or characteristics of a human individual. In other words, quality of life in this sense simply refers to an observable and ‘objective’ description about certain features or traits a person might have, and thus is morally neutral. An example of a descriptive end-of-life statement would be: ‘this person has pain’, or ‘this person has lost her or his functional ability’, or ‘this person is totally dependent on others for care’. By this view, to say someone has lost quality of life would be to say nothing more than that she or he has lost a particular property or characteristic (or set of characteristics) of life, not the value of life itself.

Quality of life in the evaluative sense, however, is quite different. Here an end-of-life statement would express that ‘some value or worth is attached to the characteristic of a given individual or to a kind of human life’ (Reich 1978: 831; see also Walter 2004). For example, an evaluative end-of-life statement might assert that ‘the pain suffered by this person is bad’ and ‘the absence of pain in this person is good’, or that ‘the loss of functional ability experienced by that person is bad’ and ‘the regaining of function by this person is good’, or that ‘this person’s dependency on others for care is bad’ and the ‘regaining of independence by this person is good’, and so on. To say a person has lost quality of life in this sense would be to assert merely that some property or aspect of her or his life has lost value, not that life itself has lost value — although the attachment of value to certain qualities or characteristics, in this instance, often becomes the very basis upon which an individual human life might be judged worth living or not worth living, and clinical decisions made accordingly (Walter 2004).

Quality of life in the morally normative or prescriptive sense, on the other hand, is quite different again. Here, an end-of-life statement would entail a moral judgment on a given (already evaluated) quality or set of qualities of an individual human life. Quality of life expressed as a moral judgment in this instance would seek to prescribe what would be a good or bad, right or wrong way of regarding a given individual human life or, more specifically, on the basis of its qualities, what ought and ought not to be done ‘to support and protect’ it. An example of a morally prescriptive end-of-life statement would be:

▪ a life marked by intense pain is a life which is not in an individual’s best interests to go on living; ending such a life would thus be a morally just thing to do, or

▪ a life free of pain is a minimally decent life, and thus one worth living; to take such a life would be morally objectionable, or

▪ a life which can be lived independently of others is a minimally decent life and therefore a life worth living; taking such a life would be morally objectionable.

In this instance, a statement concerning the loss of quality of life could be interpreted as indicating that the life in question no longer has worth and thus is dispensable. Alternatively, a statement concerning an increase in quality of life could be interpreted as indicating that the life in question has improved worth and thus warrants preservation and protection.

In light of these three different senses of quality of life, it can be seen that there is enormous potential for making mistakes when deciding end-of-life treatment options based on end-of-life considerations. This observation raises a number of important points for nurses. First, it wisely instructs the need for nurses to distinguish carefully the senses in which they might be using, or rather misusing, end-of-life statements. This is particularly important in situations where decisions need to be made about which interventions should be implemented in order to enhance or promote the objective qualities of a person’s life, and, further, about which quality or qualities ought to be enhanced or restored over others. For example, once it is identified that a person is in a state of pain which can be observed and described ‘objectively’ and that the pain in question is evaluated negatively by that person, an attending nurse will be in a relatively strong position to assert that interventions aimed at alleviating pain ought to take priority in that situation. If, however, it is determined that the person in question does not regard the pain as a disvalue, or at least regards its relief as being less valuable than, say, maintaining mental alertness, an attending nurse might be in quite a different position. Chosen interventions aimed at alleviating pain might assume quite a different priority, and indeed might take on quite a different form.

A second important point is that, by distinguishing the different senses in which the term quality of life can be used, the nurse may become more aware of the logical leap between making a descriptive judgment on the quality or qualities of a person’s life and then making a prescriptive judgment (on the basis of that descriptive judgment) concerning what ought or ought not to be done in relation to that person’s life. For example, if we distinguish between the different senses of ‘quality of life’, it soon becomes apparent that it is one thing to say a given person has lost one or two objective (descriptive) qualities or properties of their life, but it is quite another to say that, on the basis of those lost properties or qualities, the life itself of the person in question has less moral value or ought to be treated in one particular way rather than another.

Lastly, when we examine the fragile connection between the descriptive, evaluative and morally prescriptive senses of quality of life, the fundamental questions emerge of who should decide which values ought to be given to certain qualities or properties of life, and, further, on the basis of these ascribed values, of whether an individual human life in a particular context ought to be regarded as having one type or degree of moral value rather than another.

In relation to this last point, there is little doubt, at least from a moral point of view, that only the people whose lives are in question can authentically decide what values to ascribe to their qualities (properties) of life and what moral value to ascribe to their lives generally. For example, only the sufferers of their own pain can know what pain or dependency levels they can tolerate, and accordingly only they can identify the boundaries within which their pain or dependency states will be ascribed either positive or negative value. Only the sufferers of their own pain can know the point beyond which pain or dependency on others would render their life intolerable, and the point at which they would judge their life as being either morally less or morally more worthwhile. Bear in mind here that, while some might view pain as diminishing life’s worth, others might hold quite a different view. Likewise, some might consider dependency on others as diminishing their life’s worth, while others might consider it quite irrelevant to either the meaning or value of their life. What is important to understand is that, no matter how well intentioned a nurse might be, or how knowledgeable or experienced, this probably will not be enough to enable that nurse to judge correctly either the evaluative or the morally prescriptive aspects of another person’s (that is, that patient’s) ‘quality of life’. Even the descriptive aspect, for that matter, is difficult to judge, given the highly subjective nature of some so-called ‘objectively observable’ qualities, such as pain or loss of function. Since describing qualities is also very much a matter of interpreting them, there is always room for making judgment errors. It is for this reason that the people whose quality of life is at issue must be respected as the ones who ultimately are the best judges of what is to count as being in their ‘best interests’, and, further, as the ones who are best able to judge correctly what is to count as being their quality of life. In instances where people are unable (for reasons of incompetency or incapacity) to judge their own quality of life or best interests, this task should rightly fall to those (e.g. close family members and/or friends) who intimately know the person in question and who know thoroughly their world views (values, beliefs and wishes).

It can be seen that in using the notion of quality of life, nurses must be very careful to distinguish the exact sense in which they are using it. They must also be aware of how easy it is to leap from a descriptive statement concerning a person’s quality of life to a prescriptive statement on what should be done for that life — morally, medically or otherwise. Furthermore, they must take steps to guard against making this leap in judgment, particularly in instances where doing so might result in another not only losing a minimally decent level of life, but losing life itself.

A dvance directives

Under common law and in most civil jurisdictions, all adults have the right to refuse medical treatment, including life-sustaining/saving treatment (Ashby & Mendelson 2003; Lewis 2001; Mendelson & Jost 2003; Stewart 2006). Underpinning this common law right is the presumption that every adult has the mental capacity to consent or refuse to consent to any medical intervention ‘unless and until that presumption is rebutted’ (Ashby & Mendelson 2003: 261 supra note 11). Sometimes, however, people who are suffering from serious illnesses and/or who are dying will not be able to exercise their right to decide on account of having lost their capacity to make prudent and responsible life choices (i.e. they have become incompetent). In such situations, treatment decisions invariably fall to someone else — for example, the patient’s proxy (family/friends) or the health care team. Proxies and health care professionals who find themselves in this surrogate decision-making role may not, however, know what to decide. This is especially so in cases where the patient’s wishes are not known or, if known, are open to a variety of interpretations and hence dispute. Problems can also arise where proxies ‘express certainty’ regarding the preferences of the patient when, in fact, there is no clear basis for their opinions and/or where preferences collide with the values and beliefs of caregivers (Johns 1996). A critical question to arise here is: How is it best to deal with this situation and the dilemmas it poses?

During the decades of the 1980s through to the 1990s, a strong consensus emerged in the health professional literature that ‘advance planning’ has a constructive role to play in — and can be an effective guide to — end-of-life decision-making, and that the most appropriate instrument for communicating such planning is the advance directive (Council on Ethical and Judicial Affairs, American Medical Association 1999; Hammes & Rooney 1998; Jordens et al 2005; Martin et al 2000). Furthermore, it was accepted that not only could an advance directive provide guidance on ‘ how decisions are to be made, but also who is to make them’ (Buchanan & Brock 1989: 95).

W hat is an advance directive?