Donor Site Care

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

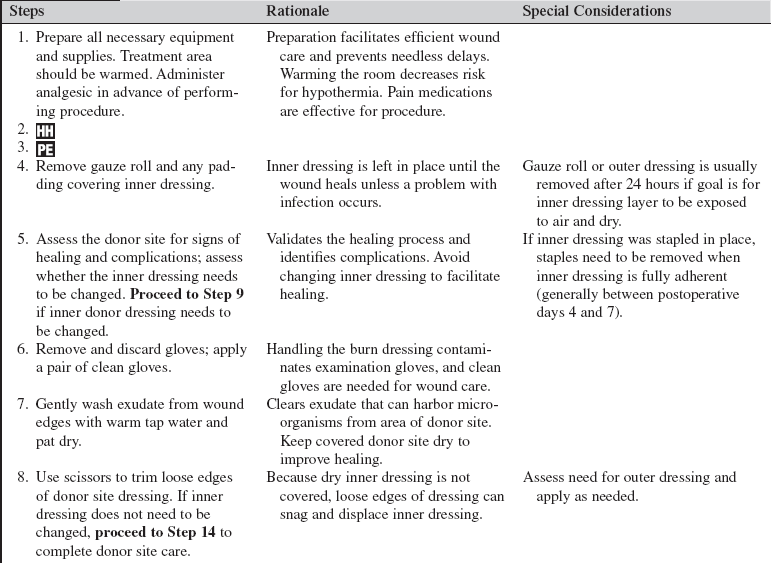

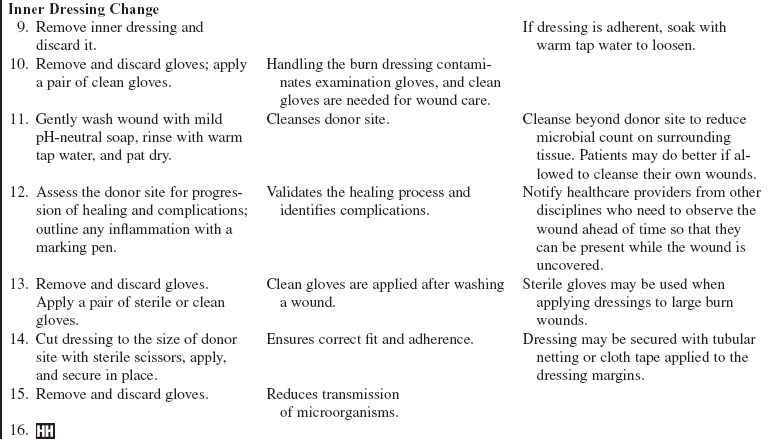

• A partial-thickness wound is surgically created when a donor site (Fig. 119-1) is harvested to obtain skin for a full-thickness defect. The more dermis moved with the skin graft, the less the graft shrinks with healing; therefore, deeper donor sites may be created to obtain skin for cosmetically significant areas such as the face or hands.9 Depending on the percentage of dermis moved with the graft, donor sites created may be superficial or deep partial-thickness wounds that heal in 10 to 20 days (typically, 10 to 14 days; Fig. 119-2).6

Figure 119-1 Fresh donor site.

Figure 119-2 Donor sites.

• Factors that can disrupt or prolong healing include infection, desiccation, edema, adherent dressing changes, poor nutrition, hemodynamic instability, and a variety of preexisting medical conditions.2

• The longer a partial-thickness wound takes to heal, the more significant the scarring; therefore, donor sites can produce minimal or hypertrophic scars.2 Donor sites retain deep epidermal appendages, so they are generally capable of sweating and bearing hair after they heal. The donor site may be reharvested once healing is complete, but skin from the first harvest of a donor site is always of higher quality than that of repeat harvesting.

• Because the dermis is richly supplied with capillaries and nerve endings, donor sites are at risk for bleeding in the first 24 hours and are exquisitely tender to touch. They produce large volumes of serous exudate.

• Donor site treatment goals include minimizing bleeding, supporting reepithelialization, managing exudate, preventing infection, controlling pain, and minimizing scarring.9 Epinephrine-soaked dressings, thrombin spray, or compression dressings may be applied in the operating room to attain stasis.9 A compression dressing is usually used for the first 12 to 24 hours to ensure stasis.8 After this initial period, compression may be applied for comfort.

• Wounds epithelialize most rapidly in a moist environment. If donor sites are small enough, use of a thin-film polyurethane or hydrocolloid dressing has been shown to promote rapid healing while providing comfort through dressing flexibility and occlusive coverage of nerve endings.6 Occlusive dressings (sealed on all sides) can be difficult to maintain on larger donor sites because of the substantial volume of exudate.6 A small drain (attached to a vacutainer and collection tube Becton, Dickinson and Co., Franklin Lakes, NJ) tube can be used to remove excess drainage from under a thin-film dressing. Calcium alginates have also been used successfully under occlusive dressings to mange exudate.6

• Multilayer occlusive dressings may also be used, with a nonstick dressing (e.g., greasy gauze, meshed silicone) applied next to the donor site and a bulky absorbent outer layer to maintain a moist environment and wick away excess drainage. The outer dressing may be changed periodically, leaving the inner dressing intact until the wound heals beneath it.

• One of the oldest and most cost-effective methods for treatment of donor sites is to apply mesh gauze, wrap with an outer wrap for 12 to 24 hours, and then remove the outer wrap and allow the inner dressing to remain exposed and dry until the wound heals beneath. This method has been done with fine mesh gauze and xeroform (McKesson Brand, San Francisco, CA)/xeroflo (Kendall Healthcare, Coviden, Mansfield, MA). The technique is only effective if the dressing dries well and becomes impermeable to bacteria, essentially acting as a scab.11 Positioning the patient for maximal exposure of the donor sites, preventing prolonged donor site contact with sheets and clothing, and increasing airflow across the wound are important for this technique to work.5 If the donor site is large, this procedure creates a rather stiff and uncomfortable protective layer.

• Biobrane (UDL Laboratories, Rockford, IL), a biosynthetic product, produces a more flexible donor site dressing. When exposed to air at 24 hours after harvesting, it dries to form a fibrous bond with the collagen in the wound. This dressing provides improved pain control, exudate management, and rate of healing when compared with a fine-mesh gauze dressing.12

• Antimicrobial creams or ointments have also been used on donor sites, essentially treating the wounds in the same way as partial-thickness burns are treated. The disadvantage to this approach is that it requires daily washing of the wound and reapplication of cream and dressings.11

• Slow-release silver dressings are gaining popularity for donor site use. These dressings are moistened twice daily with sterile water to release the silver. In highly exudating wounds, the wound moisture may be adequate to promote silver release without exogenously applied moisture. These dressings release silver for 3 or more days; ideally, they are placed on the donor site in the operating room, and the wound is allowed to heal beneath with infrequent or no dressing changes.6,11

• Donor sites need to be assessed daily for signs of infection, including periwound warmth and erythema, increased pain, and purulent drainage. Bacteria can delay healing and increase scarring or convert a partial-thickness donor site to a full-thickness wound.2 Erythema should be outlined to monitor progression, with consideration of either removing the donor site dressing or applying a topical antimicrobial to penetrate the donor site dressing. Reopening or “melting” of epithelium in previously healed donor sites is often the result of colonization with gram-positive organisms and may require antibacterial intervention.4 Heavy hair-bearing donor sites such as the scalp provide special challenges. Heavy hair growth can lead to matting of hair in the exudate, which can lead to accumulation of protein, proliferation of bacteria, and ingrowth of hair, a condition referred to as chronic folliculitis.8 This problem can lead to chronic, nonhealing, inflamed wounds or conversion of partial-thickness donor sites to full-thickness wounds. Dressings that prevent drying and wick away the exudate work well.

• Donor sites are often very painful, with the amount of pain variable depending on the dressing technique used. Patients with donor sites usually need scheduled round-the-clock pain medication.3,7

• The donor site should not be exposed to the sun for a year after the burn. Apply full-spectrum sunblock to donor sites any time exposure to the sun is anticipated.10

• Protect fresh donor sites from dependent edema by wrapping with elastic bandages before sitting or ambulating.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Teach the patient and family that donor sites generally heal in 10 to 12 days with variable scarring.  Rationale: Realistic expectations about healing and scarring are provided.

Rationale: Realistic expectations about healing and scarring are provided.

• Provide donor site care instructions, and review them with the patient and family. Demonstrate how to assess and manage the donor site dressing, and have the patient and family return the demonstration. Encourage the patient and family to ask questions. Provide positive feedback. Arrange for home care or clinic visits to follow up on dressings and wound care.  Rationale: The patient’s and family’s understanding and ability to perform wound care are validated.

Rationale: The patient’s and family’s understanding and ability to perform wound care are validated.

• Patients should be encouraged to avoid smoking.  Rationale: Smoking causes vasoconstriction, inhibits epithelialization, and decreases tissue oxygenation, all of which delay healing.2

Rationale: Smoking causes vasoconstriction, inhibits epithelialization, and decreases tissue oxygenation, all of which delay healing.2

• Explain to the patient about the pain and itching sensations associated with donor site healing.1,7  Rationale: Patients need to know that donor site pain and itching, although unpleasant, are normal and do not cause concern.

Rationale: Patients need to know that donor site pain and itching, although unpleasant, are normal and do not cause concern.

• Teach the patient and family about appropriate use of medications and nonpharmacologic interventions to manage pain and itching.1 Encourage application of a topical moisturizer after healing.7  Rationale: Comfort is enhanced.

Rationale: Comfort is enhanced.

• Teach the patient and family about signs and symptoms of infection and the importance of reporting these in a timely manner.4  Rationale: The patient and family can recognize problems early so that appropriate measures can be instituted by the healthcare providers.

Rationale: The patient and family can recognize problems early so that appropriate measures can be instituted by the healthcare providers.

• Provide the patient and family with follow-up appointments and a contact to call with any problems.  Rationale: This information is necessary for further care and follow up.

Rationale: This information is necessary for further care and follow up.

• Assess the family’s ability to provide care at home at each follow-up visit.  Rationale: Continued care of the wound is necessary after discharge.

Rationale: Continued care of the wound is necessary after discharge.

• Stress the importance of wearing pressure garments if they are indicated.  Rationale: Pressure garments reduce scarring.10

Rationale: Pressure garments reduce scarring.10

• Inform the patient and family that the donor site should not be exposed to the sun for a year after the burn. Patients should wear clothing that covers wounds or a sunscreen with SPF higher than 15.10  Rationale: The patient and family are prepared for changes that occur after healing.

Rationale: The patient and family are prepared for changes that occur after healing.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Evaluate for signs of healing, as follows:

Dressing separation at wound edges with reepithelialization beneath it

Dressing separation at wound edges with reepithelialization beneath it

Compare degree of healing with expected rate of healing based on number of days since skin harvested.

Compare degree of healing with expected rate of healing based on number of days since skin harvested.  Rationale: Healing should occur within 10 to 12 days unless complications occur.

Rationale: Healing should occur within 10 to 12 days unless complications occur.

• Evaluate for signs and symptoms of infection, as follows:

Fever or increasing white blood cell (WBC) count4

Fever or increasing white blood cell (WBC) count4

Rationale: Donor site infection may necessitate antimicrobial intervention.2

Rationale: Donor site infection may necessitate antimicrobial intervention.2

• Evaluate the adequacy of the pain control by asking the patient to rate the pain on a scale of 0 to 10, both before and during wound care.  Rationale: An individualized plan for pain control should be in place for background and procedural pain.3,7

Rationale: An individualized plan for pain control should be in place for background and procedural pain.3,7

• Evaluate the patient’s range of motion (ROM) in the vicinity of the donor site. Physical and occupational therapists may be consulted to assist the patient with maintaining ROM and with scar management.  Rationale: Wounds contract during healing; pain and tightness can decrease ROM. The patient should be encouraged to continue normal movement and ROM exercises.

Rationale: Wounds contract during healing; pain and tightness can decrease ROM. The patient should be encouraged to continue normal movement and ROM exercises.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teaching. Answer questions, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

•![]() Premedicate the patient for pain and anxiety, as prescribed. Wait to perform the procedure until the medication has had time to work.

Premedicate the patient for pain and anxiety, as prescribed. Wait to perform the procedure until the medication has had time to work.  Rationale: Waiting allows time for the medication to take effect and promotes optimal comfort for the patient. Medication reduces pain and anxiety and encourages patient trust and compliance with procedure.

Rationale: Waiting allows time for the medication to take effect and promotes optimal comfort for the patient. Medication reduces pain and anxiety and encourages patient trust and compliance with procedure.

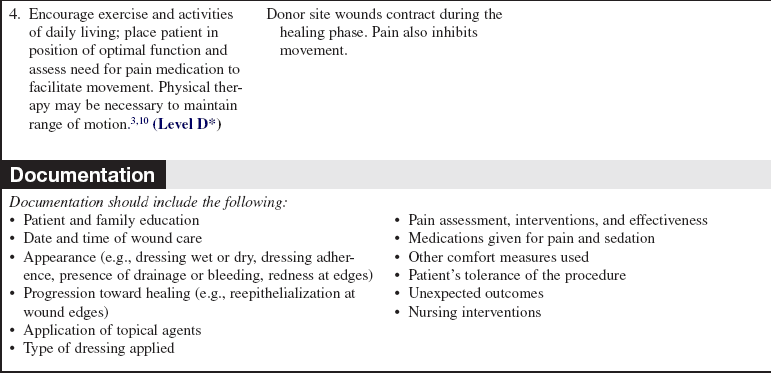

References

1. Brooks, JP, et al, Scratching the surface. managing the itch associated with burnsa review of current knowledge. Burns 2008; 34:751–760.

2. Broughton, G, et al, Wound healing. an overview. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 117:1e-S–32e-S.

3. Faucher, L, et al. Practice guidelines for the management of pain. J Burn Care Res. 2006; 27:659–668.

4. Gallagher, JJ, et al. Treatment of infections in burns. In: Herndon D, ed. Total burn care. ed 3. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:136–176.

5. Hedman, TL, et al. Two simple leg net devices designed to protect lower-extremity skin grafts and donor sites and prevent decubitus ulcer. J Burn Care Res. 2007; 28:115–119.

![]() 6. Honari, S. Topical therapies and antimicrobials in the management of burn wounds. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16:1–11.

6. Honari, S. Topical therapies and antimicrobials in the management of burn wounds. Crit Care Nurs Clin North Am. 2004; 16:1–11.

7. Meyer, WJ, et al. Management of pain and other discomforts in burned patients. In: Herndon D, ed. Total burn care. ed 3. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:797–818.

8. Mimoun, M, et al, The scalp is an adventageous donor site for thin-skin grafts. a report on 945 harvested samples. Plast Reconstr Surg 2006; 118:369–373.

9. Muller, M, et al. Operative wound management. In: Herndon D, ed. Total burn care. ed 3. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:177–195.

10. Serghiou, MA, et al. Comprehensive rehabilitation of the burn patient. In: Herndon D, ed. Total burn care. ed 3. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2007:620–651.

11. Stout, LR. Burns. In: Carlson KK, ed. AACN advanced critical care nursing. London: Saunders Elsevier; 2009:1212–1260.

12. Whitaker, IS, et al, A critical evaluation of the use of -Biobrane as a biologic skin substitute. a versatile tool for the plastic and reconstructive surgeon. Ann Plastic Surg 2008; 60:333–337.