Endoscopic Therapy

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Upper gastrointestinal (GI) hemorrhage is a relatively common, potentially life-threatening emergency that requires rapid assessment and resuscitation.11 Esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) is the diagnostic and therapeutic modality for nonvariceal and variceal upper GI bleeding.2,3,12 Endoscopic therapy reduces the rate of rebleeding, blood transfusion requirements, and the need for surgery.2,3

• Endoscopic therapies are the interventions of choice for many upper and lower GI bleeding lesions. Upper endoscopic therapies include injection therapy, ablative therapy, such as heater probe, and mechanical therapy, such as endoclips or endoscopic banding.2

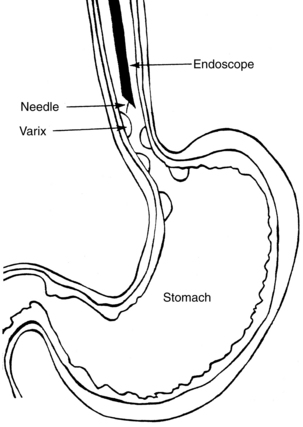

• For all upper endoscopic interventions, a fiberoptic endoscope is passed through the esophagus and into the stomach and duodenum to identify the site of bleeding. The nurse assisting the endoscopist prepares all of the equipment potentially needed during the procedure. Once the site of bleeding is found, any of the endoscopic techniques identified previously may be used.

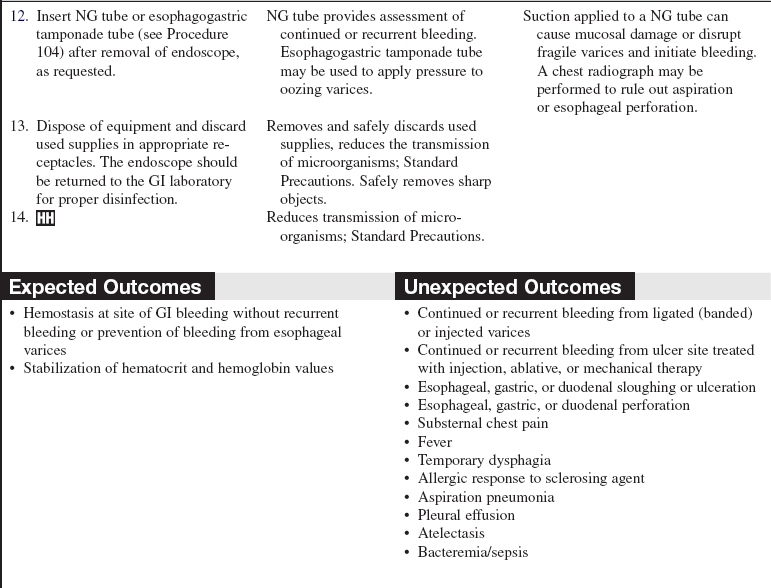

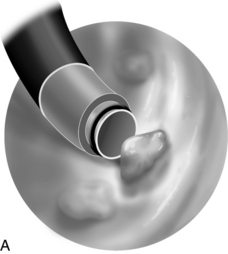

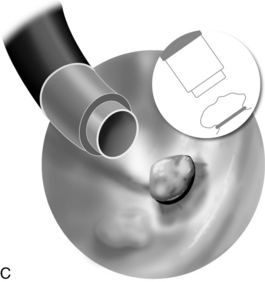

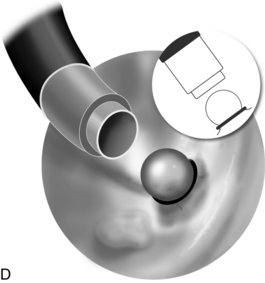

• Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL) is the preferred endoscopic method for control of acute esophageal bleeding and for prevention of rebleeding, unless excess bleeding prevents effective band placement and ligation.11 Endoscopic sclerotherapy (EST), which involves injection of a sclerosant into or adjacent to a varix, may be used. EST has largely been replaced by the use of EVL, which is a type of mechanical therapy.1,4,9,12

• For gastric varices, a promising intervention is gastric variceal occlusion (GVO) with tissue adhesives such as N-butyl-cyanoacrylate. Studies are ongoing, but tissue adhesives are not yet approved for use in the United States.9,12

• Injection therapy is used for hemostasis for bleeding from peptic ulcer disease, Mallory-Weiss tears, and other lesions and for postprocedure related bleeding.11 Epinephrine is the injection agent of choice for these maladies in the United States.2

• The several proposed mechanisms of action of the various sclerosing agents include vasoconstriction, esophageal or vascular smooth muscle spasm, compression of the bleeding vessel by submucosal edema or by the volume of sclerosing agent used (tamponade effect), and actual coagulation of the vessel. Ultimately, vessel thrombosis occurs.

• A variety of sclerosing agents are available (Table 111-1). The physician or advanced practice nurse who performs the endoscopy prescribes the agents to be used.

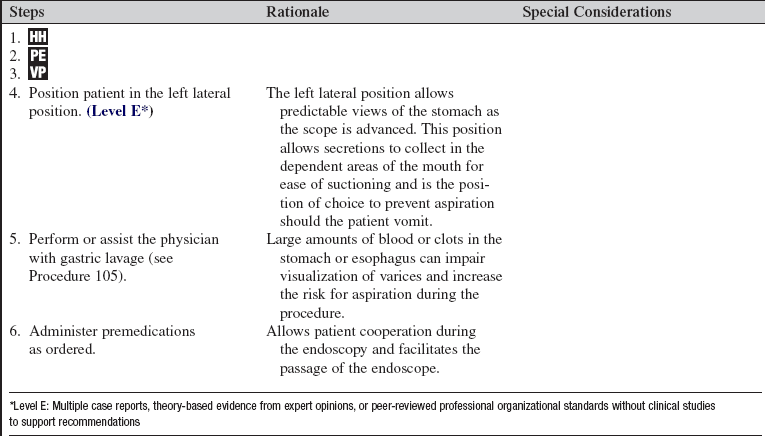

Table 111-1

| Sclerosants Used for Bleeding Varices4 | Sclerosants Used for Other Causes of Upper GI Bleeding2 |

| Sodium morrhuate (5%) | Epinephrine (1:10,000 to 1:20,000) |

| Ethanolamine oleate (5%) | Ethyl alcohol (volumes greater than 1 to 2 mL can lead to tissue damage) |

| Sodium tetradecyl sulfate | Thrombin |

| Ethanolamine acetate | Polidocanol |

| Polidocanol (0.5% to 1%) | Sodium tetradecyl sulfate |

| Ethanol (can cause ulceration) |

• Endoscopic therapy can combine a number of interventions to promote hemostasis, including esophageal band ligation, injection therapy, laser therapy, thermal coagulation, and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS), a radiologic intervention.2,11,12

• Ablative therapies, such as the use of a heater probe or bipolar electrocoagulation, are other endoscopic techniques for the management of bleeding from peptic ulcer disease and other nonvariceal causes of upper GI bleeding. These therapies are effective as they result in coagulation of a bleeding vessel.2,8

• Passage of the large-bore therapeutic endoscope may stimulate the vagal response in the patient and precipitate bradydysrhythmias.

• As a result of the sedation and topical anesthetic used, the patient’s gag reflex may be diminished or absent, putting the patient at risk for aspiration.

• Sedation can put the patient at risk for respiratory depression. A moderate sedation protocol is recommended for use to guide monitoring of the patient. This protocol should include the use of recommended monitoring and emergency equipment.

EQUIPMENT

• Therapeutic large-caliber endoscope (rigid or flexible; however, the flexible scope is the usual type used for upper endoscopy)

• Endoscopic injector needle (23- to 26-gauge, 2- to 5-mm needle; as ordered by physician)

• Three 10-mL syringes filled with sclerosing agent, as prescribed by physician

• Additional therapeutic equipment should be available for management of nonvariceal upper GI bleeding (i.e., laser or thermal equipment, endoloops or endoclips)

• Esophageal bands should be available for management of known or suspected variceal upper GI bleeding

• Suction setup with connecting tubing

• Rigid pharyngeal suction-tip (Yankauer) catheter

• Safety goggles for each healthcare provider and the patient

• Nonsterile 4-inch gauze or washcloth

• Premedications (as prescribed by physician)

• Normal saline (NS) solution or tap water for irrigation

Additional equipment, to have available as needed, includes the following:

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and indication for endoscopic therapy and the patient’s role in the procedure.  Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased.

Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased.

• Explain that the patient will be sedated for comfort and for ease in passing the endoscope.  Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased.

Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased.

• Explain that the patient will be monitored closely during and after the procedure.  Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased.

Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess for a history of upper GI bleeding, and the source of this bleeding, and baseline hematocrit and hemoglobin levels.  Rationale: This assessment is used as a basis for assessment of bleeding or continued bleeding after endoscopic therapy.

Rationale: This assessment is used as a basis for assessment of bleeding or continued bleeding after endoscopic therapy.

• Assess baseline cardiac rhythm.  Rationale: Passage of a large-bore tube may cause vagal stimulation and bradydysrhythmias.

Rationale: Passage of a large-bore tube may cause vagal stimulation and bradydysrhythmias.

• Obtain baseline coagulation study results (i.e., prothrombin time [PT], partial thromboplastin time [PTT], platelet count).  Rationale: Abnormal coagulation values increase the potential for bleeding after endoscopic therapy.

Rationale: Abnormal coagulation values increase the potential for bleeding after endoscopic therapy.

• Review respiratory, hemodynamic, and neurologic assessment before the administration of any sedative agents.  Rationale: Baseline assessment data provide information to use as a comparison for further evaluation once medications have been administered.

Rationale: Baseline assessment data provide information to use as a comparison for further evaluation once medications have been administered.

• Obtain baseline vital signs and pulse oximeter reading.  Rationale: Close monitoring of vital signs and pulse oximetry during the procedure and comparison with baseline values are essential to assess patient’s tolerance of the procedure.

Rationale: Close monitoring of vital signs and pulse oximetry during the procedure and comparison with baseline values are essential to assess patient’s tolerance of the procedure.

• Assess sedation score (Aldrete score, Ramsay scale, or the Richmond Agitation/Sedation Score are commonly used) based on blood pressure, pulse, oxygen saturation, level of consciousness, and respiratory status.  Rationale: Use of a scoring system standardizes assessment of the patient’s tolerance of moderate sedation.

Rationale: Use of a scoring system standardizes assessment of the patient’s tolerance of moderate sedation.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Ensure that informed consent has been obtained.  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

• Check that all relevant documents and studies are available before starting the procedure.  Rationale: This measure ensures that the correct patient receives the correct procedure.

Rationale: This measure ensures that the correct patient receives the correct procedure.

• Place the patient on a cardiac monitor and apply a pulse oximeter and automatic blood pressure cuff.  Rationale: This allows for close cardiovascular and respiratory monitoring during the procedure.

Rationale: This allows for close cardiovascular and respiratory monitoring during the procedure.

• Ensure venous access is in place.  Rationale: Venous access is needed for premedications and emergency medications.

Rationale: Venous access is needed for premedications and emergency medications.

• Ensure that the patient has been on nothing-by-mouth (NPO) status for at least 4 hours before the procedure.  Rationale: Undigested material in the stomach increases the risk for aspiration and decreases visualization of the GI tract.

Rationale: Undigested material in the stomach increases the risk for aspiration and decreases visualization of the GI tract.

• Have sedatives (common sedatives used include midazolam, diazepam, meperidine, and fentanyl) available (as prescribed) and administer when requested. Naloxone and flumazenil should be available for narcotic or sedative reversal.  Rationale: Sedation decreases patient anxiety and facilitates cooperation during the procedure.

Rationale: Sedation decreases patient anxiety and facilitates cooperation during the procedure.

• Set up the suction with connecting tubing and rigid pharyngeal suction tip attached and a catheter ready.  Rationale: This set up is necessary for suctioning the patient’s oral secretions during the procedure.

Rationale: This set up is necessary for suctioning the patient’s oral secretions during the procedure.

• Have atropine available at the bedside.  Rationale: Atropine is necessary if a vagal reaction occurs with the insertion and passage of the endoscope.

Rationale: Atropine is necessary if a vagal reaction occurs with the insertion and passage of the endoscope.

• Remove the patient’s dentures.  Rationale: Dentures interfere with safe passage of the endoscope.

Rationale: Dentures interfere with safe passage of the endoscope.

• Protect the patient’s eyes with goggles or a waterproof covering.  Rationale: Protection is provided against accidental exposure to blood or the sclerosing agents. Sclerosing agents are eye irritants.

Rationale: Protection is provided against accidental exposure to blood or the sclerosing agents. Sclerosing agents are eye irritants.

Figure 111-2 Endoscopic variceal ligation (EVL). A, Endoscope placement over varix. B, The varix is drawn into the distal portion of the endoscope. C, A rubber band is dropped over the varix. D, The rubber band contracts around the varix, causing it to sclerose and eventually slough. (Drawings by Paul Schiffmacher, Medical Illustrator, Medical Media Services at Thomas Jefferson University Hospital, Philadelphia.)

References

1. Abraldes, JG, Bosch, J. The treatment of acute variceal bleeding. Clin Gastroenterol. 2007; 41:S312–S317. [(Suppl)].

2. Cappell, MS, Friedel, D, Acute nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. endoscopic diagnosis and therapy. Med Clin North Am. 2008; 92(3):511–550.

3. Cappell, MS, Friedel, D, Initial management of acute upper gastrointestinal bleeding. from initial evaluation up to gastrointestinal endoscopy. Med Clin North Am. 2008; 92(3):491–509.

4. Dib, N, Oberti, F, Cales, P, Current management of the complications of portal hypertension. variceal bleeding. Can Med Assoc J. 2006; 174(10):1433–1443.

![]() 5. Di Mario F, Battaglia, G, Leandro, G, et al, Short-term treatment of gastric ulcer. a meta analytical evaluation of blind trials. Dig Dis Sci. 1996; 41(6):1108–1131.

5. Di Mario F, Battaglia, G, Leandro, G, et al, Short-term treatment of gastric ulcer. a meta analytical evaluation of blind trials. Dig Dis Sci. 1996; 41(6):1108–1131.

6. Ferri, FF. Paracentesis. In Ferri F, ed. : Practical guide to the care of the medical patient, ed 7, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2007.

![]() 7. Gisbert, JP, Gonzalez, L, Calvet, X, et al, Proton pump inhibitors versus H2 antagonists. a meta analysis of their efficacy in treating bleeding peptic ulcer. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2001; 15(7):917–926.

7. Gisbert, JP, Gonzalez, L, Calvet, X, et al, Proton pump inhibitors versus H2 antagonists. a meta analysis of their efficacy in treating bleeding peptic ulcer. Aliment Pharm Ther. 2001; 15(7):917–926.

8. Hauser SC, ed. Mayo Clinic Gastroenterology and Hepatology Board review, ed 2, Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press, 2006.

9. Longacre, AV, Garcia-Tsao G. A commonsense approach to esophageal varices. Clin Liver Dis. 2006; 10(3):613–625.

![]() 10. Messori, A, Trippoli, S, Vaiani, M, et al, Bleeding and pneumonia in intensive care patients given ranitidine and sulcralfate in the prevention of stress ulcer. a meta analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2003; 321(7):1103–1106.

10. Messori, A, Trippoli, S, Vaiani, M, et al, Bleeding and pneumonia in intensive care patients given ranitidine and sulcralfate in the prevention of stress ulcer. a meta analysis of randomized controlled trials. BMJ. 2003; 321(7):1103–1106.

11. Tariq, SH, Mekhjian, G. Gastrointestinal bleeding in older adults. Clin Geriatr Med. 2007; 23(4):769–784.

12. Toubia, N, Sanyal, AJ. Portal hypertension and variceal hemorrhage. Med Clin North Am. 2008; 92(3):551–574.

![]() 13. Tryba, M, Prophylaxis of stress ulcer bleeding. a meta analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991; 13(Suppl 2):S44–S55.

13. Tryba, M, Prophylaxis of stress ulcer bleeding. a meta analysis. J Clin Gastroenterol. 1991; 13(Suppl 2):S44–S55.

DiMaio, CJ. Nonvariceal upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Gastrointest Endosc Clin North Am. 2007; 17(2):253–272.

Heidelbaugh, JJ, Sherbondy, M, Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure. part II, complications and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006; 74(5):767–776.

Khan, S, Tudur Smith C, Williamson, P, et al. Portosystemic shunts versus endoscopic therapy for variceal rebleeding in patients with cirrhosis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2008.

![]() Leung, JW, Chung, SC. Endoscopic injection of adrenaline in bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987; 33(2):73–75.

Leung, JW, Chung, SC. Endoscopic injection of adrenaline in bleeding peptic ulcers. Gastrointest Endosc. 1987; 33(2):73–75.

Lim, CH, Vani, D, Shah, SG, et al, The outcome of suspected upper gastrointestinal bleeding with 24-hour access to upper gastrointestinal endoscopy. a prospective cohort study. Endoscopy. 2006; 38(6):581–585.

Marmo, R, Rotondano, G, Piscopo, R, et al, Dual therapy versus monotherapy in the endoscopic treatment of high-risk bleeding ulcers. a meta-analysis of controlled trials. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007; 102(2):279–289.

Shibli, AB, Tachauer, A, Smruti, R. Outpatient management of cirrhosis. South Med J. 2006; 99(6):559–561.

Siersema, PD. Therapeutic esophageal interventions for dysphagia and bleeding. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006; 22(4):442–447.

Talwalkar, JA. Cost effectiveness of treating esophageal varices. Clin Liver Dis. 2006; 10(3):679–689.

Zaman, A, Portal hypertension-related bleeding. management of difficult cases. Clin Liver Dis. 2006; 10(3):353–370.