CHAPTER 11. Ethical issues in suicide and parasuicide

L earning objectives

▪ Discuss the distinction between suicide and parasuicide and why making this distinction is important.

▪ Provide an overview of key religious and cultural processes that have historically influenced the development of punitive and stigmatising attitudes towards people who have attempted or completed suicide.

▪ Examine critically at least five criteria that must be met in order for an act to count as suicide rather than some other form of death (e.g. euthanasia).

▪ Consider arguments both for and against the proposition that people have a ‘right to suicide’.

▪ Examine critically the conditions under which a person’s decision to suicide ought to be respected.

▪ Discuss critically the ethics of suicide prevention, intervention and postvention.

I ntroduction

Suicide is recognised internationally as being a major public health issue. Defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as ‘the result of an act deliberately initiated and performed by a person in the full knowledge or expectation of its fatal outcome’, suicide accounts for an average of 16 per 100000 deaths, or one death every 40 seconds (WHO 2001a, 2007c). According to WHO, over the past 45 years, suicide rates have increased by 60% and are among the top three leading causes of death in people (male and female) aged 15–44 years. Although suicide occurs in all ages across the life span (including the very young and the very old) and in people from all walks of life, it stands universally as a leading cause of death among young adults. Although the probable ‘causes’ of suicide vary across cultures and countries, depression and substance abuse have both been implicated as critical factors leading to suicide (Rudnick 2002; Taylor et al 2007; WHO 2001a).

The figures given above do not include attempted suicide rates. While reliable data on the incidence of attempted suicide are difficult to obtain, the WHO estimates that suicide attempts occur up to 20 times more frequently than completed suicides (WHO 2007c). According to Australian estimates, for every male suicide there are approximately 30–50 attempts; and for every female suicide there are approximately 150–300 attempts (Suicide Prevention Victorian Task Force 1997: 21).It has been further estimated that of those who engage in suicidal behaviour (attempt suicide), 15% will ultimately succeed in ending their own lives (Suicide Prevention Victorian Task Force 1997: 21). Some studies (e.g. in Canada and Australia) suggest that around 5% of the population may be at lifetime risk of suicide ideation and behaviour, and that around 70% of people with suicide ideation may make no contact with medical or related service providers (de Leo et al 2005; Taylor et al 2007; Pridmore et al 2007).

Suicide is ranked as a leading cause of death in many countries (other leading causes of death are: ischaemic heart disease; cerebral vascular disease; cancer of the lung, trachea and bronchus; cancer of the stomach; female breast cancer; bronchitis, emphysema and asthma; chronic liver disease; and motor vehicle accidents). In the Australian state of Victoria, suicide deaths were once reported to have even outnumbered the state’s road fatalities (Ryle 1993). The probability that some road fatalities are also ‘autocides’ — that is, deaths as the result of premeditated suicidal automobile accidents — increases the significance of these statistics (Murray & de Leo 2007).

According to the most recent Australian suicide statistics, for the year 2004 there were 2098 registered deaths from suicide, being 1.6% of all deaths for that year (Australian Bureau of Statistics [ABS] 2007). These figures represent a decline over time in suicide deaths, notably from 2720 in 1997, and 2213 in 2003 (ABS 2007). Figures show that males (1661) were almost four times more likely than females (437) to die by suicide, and that the highest number of deaths occurred in males between 30 and 34 years, followed by males 40–44 years (ABS 2007). It should be noted that Australia once had one of the highest rates of suicide among young people aged 15–24 years, with rates in this age group tripling over the past 40 years (National Advisory Council on Youth Suicide Prevention 2000: 6). According to recent research, however, suicide rates in this population has declined significantly over the past 5 years, notably from 40 per 100000 in 1997–98, to approximately 20 per 100000 in 2003 (Morrell et al 2007). Nonetheless, suicide data show that youth suicide (particularly among males) is over-represented in remote and rural areas; and that youth suicide is also over-represented among gay and lesbian youth (especially those living in remote and rural areas), possibly accounting for up to 30% of all completed youth suicides each year (Suicide Prevention Victorian Task Force 1997: 19, 40). Explaining this statistical over-representation among gay and lesbian youth, one commentator has written that ‘homosexual orientation, cultural homophobia and geographical/social isolation are clearly a lethal mixture’ (Christian 1997: 9). Other high-risk groups include: men over 80 years of age, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people (rates have been estimated to be approximately 40% higher than the general population), the homeless, people with HIV/AIDS, and prisoners (National Advisory Council on Youth Suicide Prevention 2000: 7; O’Driscoll et al 2007; Suicide Prevention Victorian Task Force 1997: 38–40).

Suicide figures in the United States (US) are comparable with those in Australia. According to official estimates, there are approximately 30000 certified suicides (being 1.3% of all death) in the US each year, with many other probable suicides classified as ‘accidental deaths’ (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 188). Suicide is the third leading cause of death in young people aged 15–24 years, and the fifth leading cause of death in children 5–14 years (Caruso 2001). As is the case in Australia, males are four times more likely to die from suicide than females, and there is consistent evidence showing ‘unusually high rates of attempted suicide among gay [and lesbian] youth, in the range of 20–30%, regardless of geographic and ethnic variability’ (Remafedi 1994b: 7; see also Caruso 2001). As in Australia, gay and lesbian youth may comprise ‘up to 30% of completed youth suicides annually’ in the US (Gibson 1994: 15). These rates are thought to be causally linked to these youths’ traumatic experiences of coming to terms with their sexuality in contexts (such as families, communities, society as a whole) that are for the most part unsupportive, alienating and aggressively homophobic (see in particular Remafedi 1994a).

The magnitude of the child suicide problem in the US was highlighted in 1993 with the reported suicide of a 6-year-old girl, believed to be the youngest recorded suicide in the State of Florida (Power 1993: 9). The child was killed after she deliberately placed herself in front of an oncoming train. Her death was witnessed by three other children aged six, seven and eight years old respectively — all of whom ‘tried to move her as the train approached’ (p 9). The engineer was unable to stop the train ‘until nearly a kilometre after impact’ (p 9). It is believed that the little girl wanted to die so that she could ‘become an angel and be with her mother’, who was dying of cancer (p 9).

(As a point of interest, contrary to popular thought, child suicide is not an isolated or new phenomenon. During the late Middle Ages and early modern period, for instance, children under the age of 15 years were regarded as being at increased risk of suicide owing to the violent and abusive ways in which they tended to be treated during this period [Williams 1997: 153]. Today, while suicide rates are relatively low in children under 15 years of age, there has been some suggestion these may be increasing. In 1995, for example, in the Australian state of Victoria, four deaths by suicide were of children aged between 10 and 14 years [Suicide Prevention Victorian Task Force 1997: 16].)

A new and unusual dimension of the suicide problem to emerge in recent years has been the increasing incidence of cyberspace suicide pacts or ‘cybersuicide’ — that is, ‘suicides or suicide attempts influenced by the internet’ (Rajagopal 2004: 1299; see also Thompson 1999). Suicide pacts (defined as ‘an agreement between two or more people to commit suicide together at a given time and place’) are not a new phenomenon, although their incidence is relatively rare accounting for less than 1% of all suicides (Rajagopal 2004: 1298). Whereas most suicide pacts are between people who are well known to each other (e.g. spouses, siblings, friends), what has been particularly unusual about the recent spate of cybersuicide pacts is that they have been between complete strangers who, as stated by Rajagopal (2004: 1298) ‘have met over the internet and planned the tragedy via special suicide websites’.

Commentators are worried that the new cyberspace suicide networks will become ‘breeding grounds for real-life tragedies’ (Dubecki 2007a, 2007b) and will spark an epidemic of internet death pacts as despondent young people in particular — especially those immersed in a youth sub-culture of online networking — will ‘log out of life’ (Cameron 2005, 2006). The news media reported suicide pact deaths of 13 people in just 1 week in Japan in 2006 (where group suicides reportedly claimed 91 lives in 2005, eight of whom were young people aged between 10 and 19, and 40% of whom — both men and women — were in their 20s), and a similar spate of suicide pact deaths in Korea (where 191 group suicides were reported in the news media between 1998 and 2006). Reports such as these have underscored public health concerns about a cybersuicide epidemic (Cameron 2005, 2006; Sang-Hun 2007).

Australia has not been immune from the tragedy of cybersuicide. In 2007, the bodies of two teenage girls, both aged 16 years, were discovered in the Dandenong Ranges National Park east of Melbourne (Dubecki 2007a: 1). The two girls were apparently part of an ‘“emo” (short for emotional) subculture’ — named after a kind of music that is characteristically ‘emotional and confessional’ in tone (Dubecki 2007b; Oakes 2007). Young people who identify as ‘emos’ are thought to regard themselves as being emotional or depressed, prefer mixing in their own group, have particular preferences in music (e.g. post-punk, ‘emotive hard core’ or heavy metal styles), clothes, makeup and hairstyles (Martin 2006: 2). Like other dark sub-culture movements (e.g. goth), the emo sub-culture has been linked by youth mental health experts to self-harm, including suicide attempts (Martin 2006).

Suicide, by its very nature, is an extremely difficult and complex issue to address. At a personal level, the suicide of a loved one, a friend or an associate can be a devastating experience. Those ‘left behind’ may find themselves struggling ‘to make sense of the suicidal act and the causes of suicidal behaviour’ (Davis 1992: 90). They may also find themselves overwhelmed by feelings of grief, shame, remorse, anger, despair, and possibly even guilt at the thought that ‘perhaps they could have done more’ or that ‘if only they had been there … it might never have happened’. It has been estimated that for every suicide, between six and ten people (including family, friends and co-workers) are directly and strongly affected by the event (Suicide Prevention Victorian Task Force 1997: 25; Williams 1997: 224). Significantly, people bereaved by suicide are themselves 10 times more likely than the general population to die from self-inflicted deaths (Suicide Prevention Victorian Task Force 1997: 25).

Suicide is also difficult to address at a professional/therapeutic level. Even the very best of psychotherapies may still fail to prevent a person from completing a suicide; and even the very best of medical and nursing care may still fail to restore someone who has attempted suicide to a life that person regards as being ‘worthwhile’ and worth living. Equally if not more problematic are the difficulties of addressing the suicide issue at a moral level. Included among these difficulties is the challenge suicide and attempted suicide pose to fundamental moral notions about the value, sanctity and meaning of life. An important question here is not ‘how to achieve a better more fruitful [good] life’ — a central question in Western moral philosophy — but, as Heyd and Bloch (1981: 185) point out, ‘whether to live at all’. More seriously, suicide challenges morality itself, and not least the values, standards and principles comprising it which might otherwise be appealed to for guiding deliberation on such issues as the entitlements and responsibilities of people contemplating suicide; the moral permissibility and impermissibility of suicide prevention; the entitlements and responsibilities of others towards those contemplating or attempting suicide; and other similar issues. Compounding the moral complexity of these issues is the additional consideration that, unlike other causes of death, suicide (or, more specifically, death from suicide) is relatively preventable (Baume 1988: 43).

Nurses who have either cared for a person who has attempted suicide, or who have been involved in the care of family members and friends of someone who has attempted suicide or succeeded in suiciding, will be only too familiar with the deep emotional agony that inevitably comes with this kind of situation. They will also be very aware of the complex moral problems that are commonly associated with implementing interventions aimed at preventing suicide, with caring for those who have attempted unsuccessfully to suicide, and with the difficulties of addressing these problems in a satisfying and helpful way.

It is not the purpose of this discussion to examine or present a treatise on the clinical aspects of suicide (its underlying causes and means of prevention), or, indeed, on the philosophy or sociology or anthropology of suicide. Such a task would require major works in their own right — as has already been undertaken (see, e.g. Battin 1982, 1996; Battin & Mayo 1980; Clemons 1990; Colt 1991; Durkheim 1952; Farberow 1975a; Firestone 1997; Hendin 1998; Kaplan & Schwartz 1993; Miller 1992; Stengel 1970). Rather, the task here is to assist nurses to gain an understanding of the moral aspects of suicide and suicide prevention, and the nature of nurses’ moral obligations when caring for people who are contemplating or who have attempted suicide. In undertaking this task, attention will be given to examining briefly:

▪ the history of suicide in different cultures and societies

▪ definitions of suicide, and possible criteria that must be met in order for an act to count as suicide

▪ some important moral concerns that are raised by the suicide question, and which have significant implications for the profession and practice of nursing.

S ocio-cultural attitudes to suicide: a brief historical overview

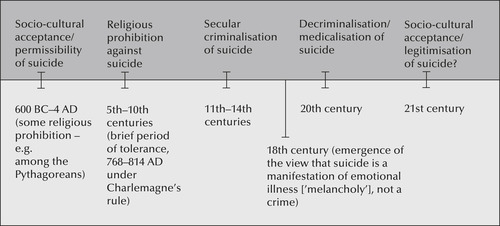

Concepts of and attitudes towards suicide have varied enormously across different cultures and throughout time (see in particular Farberow’s [1975a] Suicide in different cultures). Just what was regarded as an act of suicide and whether suicide was approved or disapproved depended on a range of factors, including cultural norms and mores, religion, law, politics, and personal and social morality (Alvarez 1980; Amundsen 1989; Battin 1982, 1996; Beauchamp 1989; Beauchamp & Childress 2001; Beauchamp & Perlin 1978; Brody 1989b; Cooper 1989; Farberow 1975b; Ferngren 1989; Hendin 1998; Miller 1992; Stengel 1970). These factors have seen Western attitudes towards suicide shift dramatically from those of socio-cultural approval through to religious prohibition, criminalisation, and ultimately the medicalisation of suicide (see Figure 11.1).

|

| Figure 11.1 |

S ocio-cultural acceptance of suicide, 600 BC—4 AD

In the introduction to Suicide: the philosophical issues, Battin and Mayo (1980: 1) note that ‘suicide has not always been assumed to be tragic or a phenomenon that is always to be prevented’. They go on to point out that, in both the early Greek and the Hebrew cultures, ‘suicide was apparently recognised as a reasonable choice in certain kinds of situations’, and that for some early North African Christians, ‘suicide — like martyrdom — was a mark of religious devotion practised as a way of insuring attainment of immediate salvation’ (Battin & Mayo 1980: 1).

In Ancient Greece and Rome, suicide was viewed as permissible (at least for the upper classes1) if it was chosen for ‘the best possible reason’ (Alvarez 1980: 18). The ‘best possible reasons’ included to preserve honour; to avoid dishonour or ignominy; as an expression of grief or bereavement; and for high patriotic principle or for a patriotic cause (Farberow 1975b: 5; Alvarez 1980: 18). There are many famous examples of suicide deaths in the history and mythology of ancient Greece and Rome. Notable among these are the Greek mythological character Jocasta (the mother of Oedipus, King of Thebes), who hanged herself to avoid the grief and shame she felt upon learning of her unwitting complicity in the sins imposed on her by fate (Sophocles 1911, vv 1213–86); Socrates, the famed ancient Greek philosopher, who killed himself patriotically by drinking hemlock after he was sentenced to death for corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens with his philosophical ideas (see Plato’s Euthyphron, Apology, Crito, and Phaedo in Church’s [1903] translation The trial and death of Socrates, and in Tredennick’s [1969] translation The last days of Socrates); and the Roman matron Portia, who, upon learning of the death of Brutus at Philippi, killed herself by swallowing red-hot coals in what French (1985: 142) suggests was a kind of suttee. Zeno, the founder of Stoic philosophy (who apparently supported Seneca’s view that suicide was permissible, but only as a last resort in the case of intractable suffering), also suicided. He apparently hanged himself in disgust at the age of 98 after falling and dislocating a toe! (Farberow 1975b: 5). The Roman view of suicide was perhaps among the most liberal during this period. Alvarez comments (1980: 23):

… the Romans looked on suicide with neither fear nor revulsion, but as a carefully considered and chosen validation of the way they had lived and the principles they had lived by … To live nobly also meant to die nobly and at the right moment. Everything depended on the dominant will and a rational choice.

Not all the ancient Greeks and Romans had a permissive attitude to suicide, however. The Pythagoreans, for example, were vehemently opposed to suicide on religious grounds (Wennberg 1989: 41). And both the famed ancient Greek philosophers Plato and Aristotle opposed suicide, on religious and secular grounds respectively (Wennberg 1989: 42). While Plato was sympathetic to suicide ‘when external circumstances became intolerable’ (Alvarez 1980: 20), Aristotle (Aristotle 1976a: 130 [1116a 12–15]) was opposed even to this, on the grounds that:

… to kill oneself to escape from poverty or love or anything else that is distressing is not courageous but rather the act of a coward, because it shows weakness of character to run away from hardships, and the suicide endures death not because it is a fine thing to do but in order to escape from suffering.

Aristotle also opposed suicide on the economic grounds that it deprived ‘society of one of its productive members’ (Wennberg 1989: 42). Interestingly, extant taboos against suicide in the city of Athens saw the corpse of the suicide victim ‘buried outside the city, its hand cut off and buried separately’ (Alvarez 1980: 17). Alvarez points out, however, that suicide taboos and the treatment of corpses in these instances were linked not so much as might be thought to religious prohibition or to Aristotelian notions of one’s duty to contribute productively to the state. Rather, they were linked ‘with the more profound Greek horror of killing one’s own kin. By inference, suicide was an extreme case of this, and the language barely distinguishes between self-murder and murder of kindred’ (Alvarez 1980: 18).

In Rome, on the other hand, while permissive attitudes towards suicide were enshrined in law (Alvarez 1980: 22), there were exceptions based on practical and economic grounds. For example, it was a criminal offence for a slave to suicide, since it deprived the master of his capital investment (if this offence was committed within the first six months of a slave being purchased, he could be returned dead or alive to the original master and a refund obtained) (p 23). Soldiers who suicided were also deemed to have committed a serious offence — ‘desertion’. This was because a soldier was ‘considered to be the property of the state [a chattel] and his suicide was tantamount to desertion’ (p 23). Finally, it was considered an offence for a criminal to suicide ‘in order to avoid trial for a crime for which the punishment would be forfeiture of his estate’ (p 23). Relatives were, however, entitled to defend the accused in his absence. If successful, they would retain property rights to the deceased’s estate; if unsuccessful, they would forfeit all property rights, and the deceased’s estate would go to the state. Thus, as Alvarez concludes (p 23):

… suicide was an offence against neither morality nor religion, only against the capital investments of the slave-owning class or the treasury of the state.

There are many other examples of old and ancient cultures in which suicide was tolerated, permitted and even esteemed: the Druids, for example, viewed suicide as a passport to paradise, and as a means of accompanying their departed friends (Alvarez 1980: 13); in Japan, suicide was ritualised in the form of seppuku or hara kiri (more commonly known in the variant spelling harikari) (Farberow 1975b: 3; Smith & Perlin 1978: 1622); and in India and China, the ceremonial sacrifice of widows (of which the Hindu custom of suttee is an example) was also common (Wennberg 1989: 39). (Whether this ‘ceremonial sacrifice’ should be viewed as suicide rather than homicide is, however, a contentious point — see, e.g. Daly 1978: 114–33.)

Perhaps some of the most poignant examples of the tolerance, if not the permissibility, of suicide can be found in the early Jewish and Christian traditions. Suicide in the orthodox Jewish tradition has been and continues to be viewed as a sin, and is expressly forbidden (Smith & Perlin 1978: 1622; Kaplan & Schwartz 1993). In the past, as in other societies, suicides in Jewish communities have resulted in the people who have suicided being denied full burial honours and other associated rituals; for example, mourning (Farberow 1975b: 4; Wennberg 1989: 48) — although it should be noted that attitudes have changed. Today, both contemporary and many orthodox rabbis (if satisfied that the suicide was precipitated by mental illness) now bury suicide victims alongside others in consecrated ground.

Despite suicide being regarded as a sin, not all who have taken their own lives purposely have been regarded as sinners in Jewish thought. Possibly one of the most famous examples of this can be found in the mass ‘self-killings’ in 73 AD of 960 Zealots (men, women and children) at Masada, on the western shore of the Dead Sea. In this instance, the Zealots preferred to die at their own hands rather than submit to the Roman legions surrounding their sanctuary (Wennberg 1989: 49–50; Battin 1982: 166; Alvarez 1980: 17; Farberow 1975b: 4). Likewise the ‘self-killings’ that occurred during the crusades, notably in Mainz in 1096 and York 1196 (Ben-Sefer 2003). In the York incident, for example, after killing their wives and children, a select group of 60 men ‘sacrificed themselves’ (with rabbinical sanction); the men were killed by their rabbi who, in turn, then killed himself (Ben-Sefer 2003). In more recent history, in what has been referred to as ‘the incident of the ninety-three maidens’ (Wennberg 1989: 50), 93 Jewish female students and teachers (including the head teacher) chose to take their own lives rather than to submit themselves to the infamous Gestapo for ‘immoral purposes’. Describing the incident, Battin writes (1982: 166):

During the Second World War, the directress of an orthodox Jewish girls’ school in a Nazi-occupied city came to understand that her girls, ranging in age from twelve to eighteen, had been kept from extermination in order to provide sexual services for the Gestapo. When the Gestapo announced its intention to avail themselves of these services — ordering the directress to see that the girls were washed and prepared for defloration by ‘pure Aryan youth’ — she called an assembly and distributed poisons to each of the students, teachers and herself. The ninety-three maidens, as they came to be called, swallowed the poison, recited a final prayer, and died undefiled.

Commenting on this mass suicide, Wennberg (1989: 50) explains that, like the suicide of the 400 children facing defilement in the Talmud, rather than this act being viewed as a sin it would be viewed as ‘an act of faithfulness to God’; that is, of the victims submitting themselves to God’s purpose, rather than to the immoral purposes of the men who would violate them. A more recent interpretation of these historical events, however, suggest that the incidents were not merely acts of ‘suicide’, but in keeping with a more general understanding of Jewish thought, the enactment of Kiddush HaShem — that is, a sacrifice that would sanctify the Lord (Ben-Sefer 2003).

The Christian religion, and more specifically its sacred writings, the Bible, also offers some interesting examples of tolerant if not permissible attitudes towards suicide (Farberow 1975b: 4; Rauscher 1981: 105–7; Smith & Perlin 1978: 1622; Wennberg 1989: 47). The first and perhaps most poignant example of all is what Wennberg (1989: 45) describes as the Bible’s ‘curious silence’ on the subject of suicide. Indeed, as Smith and Perlin (1978: 1622) also observe, ‘the Bible contains neither an explicit word for suicide nor an explicit prohibition of the act’.

Despite the apparent omission of an explicit condemnation of suicide, there are a number of significant and famous incidents of suicide mentioned in the Bible:

▪ Samson, who pleaded ‘Let me die with the Philistines’ as he toppled the temple filled with God’s enemies and was crushed to death (Judges 16: 30)

▪ Saul, who ‘took a sword and fell on it’ (1 Samuel 31: 4)

▪ Saul’s armour-bearer, who ‘also fell on his sword’ (1 Samuel 31: 5)

▪ Zimri, who ‘burned the King’s house down upon himself with fire, and died’ (1 Kings 16: 18)

▪ Judas, who ‘went and hanged himself’ (Matthew 27: 5).

Another (although less certain) Biblical example of suicide (contrary to popular thought, it may in fact be more an example of euthanasia) is the case of Abimelech (Judges 9: 52), who, in the course of attempting to set fire to a tower in which men and women had locked themselves for protection, was seriously injured after a woman in the tower ‘dropped an upper millstone on Abimelech’s head and crushed his skull’ (Judges 9: 53). Fearing that his manner of death would tarnish his posthumous reputation, he begged his young armour-bearer:

‘Draw your sword and kill me, lest men say of me, “A woman killed him”.’ So his young man thrust him through, and he died.

(Judges 9: 54)

Some even suggest that the death of Jesus Christ is an example of suicide (Alvarez 1980: 12; Rauscher 1981: 107). Whether Jesus’ death can be regarded as suicide, however, depends entirely on how suicide is defined.

The Bible’s apparent failure to prohibit or condemn suicide explicitly, while significant, should not be taken as implying Christian approbation of the act. As Wennberg (1989: 46) points out, acts of suicide are — and have long been — incompatible with Christian theology (see also Amundsen 1989: 77–153; Beauchamp 1989: 183–219; Boyle 1989: 221–50; Ferngren 1989: 155–81; Kaplan & Schwartz 1993). The only apparent exception to this prohibition, at least until the teaching of St Augustine, was if suicide was the only option available in order to ‘protect one’s virginity or to avoid forced apostasy’ (Battin 1982: 3, 70–1).

A ttitudes of religious prohibition against suicide

Until about 250 AD, attitudes towards suicide were largely permissive, and suicide was common even among the early Christians (Farberow 1975b: 6; Alvarez 1980: 12; Battin 1982: 71). In fact, the rise of Christianity as a persecuted religion brought with it an ‘almost epidemic rate of self-destruction’, justified as martyrdom (Heyd & Bloch 1981: 191). The reasons for this martyrdom are said to have included (Farberow 1975b: 6):

pessimism, longing for a better life, a struggle for redemption, and a desire to come before God and live there forever.

The religious fathers of the day were, however, appalled by the ‘squandering of human life’, and sought to halt it immediately by making it the subject of explicit and absolute religious prohibition (Wennberg 1989: 54). Thus, writes Farberow (1975b: 6):

As the 4th century began, changes appeared, with the Church adopting a hostile attitude that progressed from tentative disapproval to severe denunciation and punishment. Antagonism toward suicide developed. Suicide became proof that the individual had despaired of God’s grace, or that he [sic] lacked faith and was rejecting God by rejecting life, God’s gift to man [sic].

The church’s emphatic and official prohibition saw a marked decline in the incidence of suicide, with one writer commenting that, by the 12th century, ‘while the Catholic Church held sway in Europe, suicide became practically unknown’ (Farberow 1975b: 6).

Two highly influential figures in the fight against suicide/martyrdom were the Christian theologians St Augustine (354–430 AD) and St Thomas Aquinas (1225–74). St Augustine’s principal theological argument against suicide rested on his interpreting the sixth commandment (‘thou shalt not kill’) as applying not only to homicide (the killing of another), but to suicide (the killing of the self) (Heyd & Bloch 1981: 191). Rejecting the popular view at the time that suicide was a way of avoiding sin and gaining a passport to eternal paradise, St Augustine countered that ‘suicide is itself the gravest sin’ (Heyd & Bloch 1981: 191). Thus St Augustine denounced suicide ‘as a crime under all circumstances’ — a view that was quickly ratified as the official view of the Church (Stengel 1970: 68). In 452 AD, for example, the Council of Arles declared the act of suicide to be ‘an act inspired by diabolical possession’; one century later, the Church set another disincentive to suicide, this time by ordaining that ‘the body of the suicide be refused a Christian burial’ (Stengel 1970: 69).

St Thomas Aquinas’ views against suicide were as absolute and as uncompromising as were St Augustine’s (Wennberg 1989: 65). His arguments were, however, more systematic (Heyd & Bloch 1981: 191) and less vulnerable to criticism (Wennberg 1989: 66). Central to Aquinas’ position were the arguments that suicide constituted an offence to and a violation of one’s duty to oneself, the community, and God; he also regarded suicide as ‘contrary to the natural law and to charity’, and hence wrong (St Thomas Aquinas 1978: 103–4). Whether suicide is, in fact, any of these things has been and remains the subject of much controversy, which will not be settled here (see, e.g. Barrington 1983; Battin 1982, 1996; Battin & Mayo 1980; Beauchamp 1978b, 1978c; Brandt 1978, 1980; Brody 1989a; Donnelly 1990; Hume 1983; Kant 1983; Margolis 1975; Szasz 1988; Wennberg 1989).

As Christian religious prohibition against suicide spread across Europe, so too did ‘the acts of violence and indignity perpetrated against the dead body’ — partially, at least, because of ‘fears of evil spirits released by the suicide’ (Stengel 1970: 69). In some countries, for example, ‘a stake was driven through the body and it was buried at the crossroads’ (Stengel 1970: 69; Farberow 1975b: 7); an alternative to skewering the body with a stake was to place a stone on the face of the corpse, which would have the same effect as a stake — namely, it would prevent the victim from ‘rising as a ghost to haunt the living’ (Alvarez 1980: 8). The last degradation of the corpse of a person who had suicided occurred as recently as 1823 in England, when a Mr Griffiths was buried at the crossroads of Grosvenor Place and King’s Road, Chelsea (Stengel 1970: 69; Alvarez 1980: 8). For 50 years after this, however, the bodies of suicide victims were still not treated with full respect, and, if unclaimed, were donated legitimately to schools of anatomy for dissection (Alvarez 1980: 8).

In France, as in England, it was also common practice to treat the corpse of a suicide victim in a violent and undignified way. Alvarez writes (1980: 9), for example, that:

… varying with local ground rules, the corpse was hanged by the feet, dragged through the streets on a hurdle, burned, thrown on the public garbage.

As well as this, as in other European countries, the property of suicide victims was legally confiscated, and their memories legitimately defamed (Alvarez 1980: 9; Stengel 1970: 69). Perhaps worst of all, especially for followers of the Christian faith, was the punishment of being denied a proper Christian burial within the consecrated grounds of the church — a punishment which existed around the world right up until the 1960s and 1970s, and which may still exist in some countries even today. In 1968, for example, a US study of Roman Catholic and Greek Orthodox priests in Los Angeles found that suicide victims were still sometimes — albeit rarely — denied Christian burial (Demopolous 1968, cited in Farberow 1975b: 12). Apparently the many sympathetic priests who were burying suicide victims essentially overcame canonical prohibitions against providing Christian burials to suicide victims by accepting that the deaths in question were either ‘accidental’, ‘natural’ or the ‘irresponsible act of an unsound mind’, and hence not a culpable sin (Farberow 1975b: 12–13; Donnelly 1990: 9). In the mid-1970s, a similar situation existed in Catholic Italy. In an article examining the psycho–cultural variables in Italian suicide, Farber noted (1975: 179):

Suicide is more severely disapproved and regarded with more horror than in many other countries. A suicide cannot be buried in sacred ground; the family is grievously shamed. On a practical level, for example, an applicant will be rejected by the police force if there has been a suicide in the family. It is understandable, therefore, that a sympathetic doctor, priest, or police official will collaborate in having a suicide reported as a death from some other cause. Such behaviour is widely accepted in the Italian culture, in which family loyalty outweighs the value of civic responsibility.

Significantly, this collaboration has resulted in what Farber describes as a ‘severe distortion of official statistics on suicide and the reasons for suicide’, with ‘mental illness’ being cited as the main reason (Farber 1975: 179). This is because (p 180):

… in the eyes of the Church, only suicide by a sane person, who is responsible for his [sic] decision, is a sin. The label of mental illness allows for normal, religious burial and provides a shield for the family.

T he criminalisation of suicide

Prohibitions against and punishments for suicide were not only enshrined in and made a part of canon law. Under the influence of religious views, sanctions against suicide were also enshrined in (secular) common law (Stengel 1970: 70). Opinion varies on when suicide was first deemed a crime in England; some suggest that it could have been as early as the 10th century, while others contend that it was not until as late as 1485 (Stengel 1970: 70). By around 1554, however, suicide was definitely ‘equated with murder as a criminal offence ( felo de se) and attempted suicide a misdemeanour’ (Stengel 1970: 71). Legislation in other European countries also viewed suicide as a crime equivalent to murder, and worse. In 1670, for instance, pressure from the Church saw secular legislation enacted making suicide ‘not merely murder but high treason and heresy’ (Farberow 1975b: 9).

Anti-suicide legislation, like its counterpart in canon law, brought with it inordinate prejudice and penalties against suicide. This resulted in bizarre treatment of those unfortunate enough to be caught surviving a suicide attempt. An example of the gross inhumanity that anti-suicide legislation could both prescribe and enforce can be found in what was probably a public execution held some time during the 1860s in London and reported in the contemporary press. (Note: executions in England were public until 1868 [Carr 1961: 336].) Nicholas Ogarev, a Russian exile staying in London at the time, described the incident in a letter to his beloved, Mary Sutherland:

A man was hanged who had cut his throat, but who had been brought back to life. They hanged him for suicide. The doctor had warned them that it was impossible to hang him as the throat would burst open and he would breathe through the aperture. They did not listen to his advice and hanged their man. The wound in the neck immediately opened and the man came to life again although he was hanged. It took time to convoke the aldermen to decide the question what was to be done. At length the aldermen assembled and bound up the neck below the wound until he died. Oh my Mary, what a crazy society and what a stupid civilisation.

(quoted in Carr 1961: 336)

This example of gross inhumanity and absurdity — and the ‘weird vindictiveness [of] condemning a man to death for the crime of having condemned himself to death’ (Alvarez 1980: 8) — was sanctioned by both the Church and the state. Further, this ‘weird vindictiveness’, as Alvarez (1980: 8) describes it, did not end until almost 100 years after this incident occurred. Stengel (1970: 71) comments, for example, that even as late as 1946–55 in England and Wales, 5794 people were brought to trial for attempting suicide. Of these, 5447 were found guilty; and of these, 5138 were fined or put on probation, and 308 were sentenced to prison without the option of a fine or probation (Stengel 1970: 71). The capricious way in which the law was implemented is exemplified by a 1955 English case in which a ‘sentence of two years’ imprisonment was imposed on a man for trying to commit suicide in prison’ (Stengel 1970: 71).

As religious and social opponents of suicide began to lose their influence, the old, cruel, prejudicial, religiously based superstitious attitudes against suicide and attempted suicide gradually changed. Medical dogma replaced religious dogma, and suicide came to be viewed as the act of a ‘diseased mind’, rather than a diseased (‘diabolically possessed’) soul. Laws prescribing the desecration of corpses and the confiscation of property were abolished (Farberow 1975b: 12). In 1961, England decriminalised suicide (Stengel 1970: 71; Glover 1977: 170; Browne 1990: 10). In Canada, suicide was decriminalised in 1972; and in the US, while attempted suicide continues to be illegal in some states, suicide itself ‘is not illegal in any state’ (Browne 1990: 10).

Just over 200 years ago, in 1790, France emerged as the first country to repeal its anti-suicide legislation (Stengel 1970: 71). Two centuries later, ‘both suicide and attempted suicide are not criminal events in any civilised society’ (Browne 1990: 10).

T he medicalisation of suicide

The pressure to reform anti-suicide legislation came mainly from doctors, followed by sympathetic magistrates, and lastly members of the clergy (Stengel 1970: 71). However, the medical profession’s political lobbying in this instance achieved considerably more than mere legislative reform; it also achieved legitimation of the medicalisation of suicide. In England, for example, soon after the 1961 Suicide Act was passed, the Ministry of Health in London advised all doctors and relevant health authorities that:

attempted suicide was to be regarded as a medical and social problem and that every such case ought to be seen by a psychiatrist.

(Stengel 1970: 72)

Whether this ‘reform’ has been, as Stengel (1970: 72) claims, a less ‘moralistic and punitive reaction’ than that expressed in former legislation remains to be seen. Those who attempt suicide are still frequently the subject of ‘negative attitudes’ by whole communities (see Cvinar 2005; Sarfraz & Castle 2002) and even by attending health care professionals who are supposed to ‘care’ for them (Bailey 1998; Baume 1988; Donnelly 1990; Dunleavey 1992; Knight 1992; Lindars 1991; McAllister et al 2002; Morse 2001); further, they can still find themselves incapacitated involuntarily by the law. As Beauchamp and Childress (2001: 190) point out:

Although suicide has been decriminalised, a suicide attempt, irrespective of motive, almost universally provides a legal basis for public officers to intervene as well as grounds for involuntary hospitalisation.

As well, social and religious taboos still necessitate a degree of secrecy about the circumstances of a person’s ‘unexpected illness’ or ‘accidental death’. Donnelly (1990: 9) claims that the legacy of past taboos concerning suicide still sees doctors and coroners pressured into using euphemisms when officially certifying or describing the cause of death of a suicide victim. In one notable example, a British report described as ‘accidental’ the death of a man ‘who just happened to shoot himself while cleaning the muzzle of his gun with his tongue’! (Donnelly 1990: 9).

Arguably, one of the most potent examples of sidestepping any reference to suicide can be found in the aftermath of the terrorist attack on the twin towers of the World Trade Center in New York on September 11, 2001. It has been conservatively estimated that between 7% and 8% of people who died that day were ‘jumpers’. This figure is based on film footage and eyewitness accounts of people ‘jumping continually’ — from all four sides of the buildings and from all stories, the 106th and 107th floors and the top of the building — to escape the inferno around them. It is further reported that people kept jumping until the towers collapsed (Junod 2003). Yet, despite these reputable estimates and eyewitness accounts, and a description of ‘the jumpers’ as victims who, of terrible necessity ‘engaged in mass suicide’, the New York Medical Examiner’s Office (coroner) denied that anyone had ‘jumped’ (Junod 2003). According to Junod (2003), when researching the story he had been assigned to write for Esquire magazine, rather than answers, he got admonitions from authorities: ‘ “We don’t like to say jumped. They didn’t jump. Nobody jumped. They were forced out, or blown out” ’ — in short ‘there were no jumpers here’. In a 2006 Australian Broadcasting Corporation (ABC) documentary on Junod’s investigation, it was revealed that not one of the ‘jumper’ deaths had been registered as a suicide with the Medical Examiner’s office (ABC 2006). Had they been so registered, the documentary revealed that life insurance policy payouts could have been denied, and victims could have been deemed to have committed a sin by their church and denied full burial honours and other associated religious rituals (ABC 2006).

The ‘medical gaze’ of ‘the clinic’ (Foucault 1973) may well prove ultimately to be a more humane alternative than the punitive gaze of criminal law — thought to be justified as a system of ‘moral accounting’ (Foucault 1973: 250). When I think of the many people — young and old, vulnerable and desperate — who have been admitted to hospital following a failed suicide attempt, and in whose care I have been involved (mostly in accident and emergency departments or intensive care units), I am inclined to think that the anti-suicide law reforms we inherited in the 20th century have not really changed the status quo. These law reforms have resulted not so much in the decriminalisation of suicide as in the medicalisation of the law: where once suicide victims and their families were made to account to the law, now they must account to medicine (psychiatry); where once suicide victims were made to prove their innocence before the law, now they must prove their competence; and where once those who attempted suicide were imprisoned for the crime of stealing the gift of life from God, now they are hospitalised involuntarily for violating the gift of civil liberty from society. As Alvarez observes (1980: 31):

modern suicide has been removed from the vulnerable, volatile world of human beings and hidden safely away in the isolation wards of science. I doubt if Ogarev [the Russian exile] and his … mistress would have found much in the change to be grateful for.

Over the past few decades there has been a renewed interest in the moral aspects of suicide, prompted largely by the euthanasia/euthanatic suicide (assisted suicide) debate (discussed in Chapter 10 of this book), and increasing public demand for the ‘right to die’ to be enshrined in law. This renewed interest has, arguably, marked the beginning of a trend back (rightly or wrongly) to permissive attitudes towards suicide and, more specifically, the socio-cultural normalisation of suicide — particularly in cases of intolerable and intractable suffering — both physical and mental (see Figure 11.1). It is no small irony, however, that whereas in the ancient world economic considerations provided the grounds for the legal prohibition of suicide (particularly among the poor and working classes) and for the just punishment of those who attempted suicide, in the modern world economic considerations will probably provide many of the grounds for legalising suicide (and more particularly, euthanasia/assisted suicide). This is especially likely in the contexts where the financial and other material costs associated with caring for people with end-stage illnesses becomes burdensome and go beyond what can be ‘reasonably sustained’ (examples of which were given in Chapter 6 of this book; see also Battin 1982, 1996).

D efining suicide

Before examining some of the moral issues raised by the suicide question, it is necessary first to establish at least a working definition of suicide — a term which, incidentally, entered the English language only in 1651 (Wennberg 1989: 17; Battin 1982: 22–58).

The word suicide comes from the Latin sui, ‘of oneself’ and cidium, ‘a slaying’ (from caedere, ‘to kill’). Like many other terms used in moral discourse, suicide is not easy to define; indeed, there is no universally agreed definition of what suicide is, or of what criteria should be met in order for an act to count as an instance of suicide. As Margolis (1978, reprinted in Beauchamp & Perlin 1978: 92–3) explains, the ‘culturally variable character of suicide’ has given rise to many competing views on what it is, with the unhelpful consequence that some acts have been included as suicide and others firmly excluded. This, in turn, has had some important practical consequences, including the difficulty of ascertaining accurate and comparable statistics on the incidence and causes of suicide (Beauchamp 1980: 68–9).

For Wennberg (1989: 17), wrestling with the problem of defining suicide is to be taught a lesson in ‘linguistic humility’. Nevertheless, our commonsense notions of what suicide is, our ability to recognise instances of suicide and to distinguish these from other kinds of death (e.g. homicide, patricide, matricide, fratricide, sororicide, infanticide, regicide and euthanasia or euthanatic suicide [Battin 1982: 20]), and the very existence of terms in our language which make it possible to speak of suicide as a distinctive kind of death, all provide grounds for optimism about our ability to achieve at least a working — if not a universal — definition of suicide.

According to Stengel (1970: 77), a commonsense notion of suicide can be expressed in the following terms:

A person, having decided to end his [or her] life, or acting on a sudden impulse to do so, kills himself [or herself], having chosen the most effective methods available and having made sure that nobody interferes. When he [or she] survives he [or she] is said to have failed and the act is called an unsuccessful suicide attempt. Death is the only purpose of this act and therefore the only criterion of success. Failure may be due to any of the following causes: the sense of purpose may not have been strong enough, or the act may have been undertaken half-heartedly because it was not quite genuine; the subject was ignorant of the limitations of the method; or he [or she] was lacking in judgment and determination through mental illness.

This definition is not, of course, without controversy. For example: What constitutes a ‘genuine’ suicide attempt? When is a suicide attempt to be regarded as ‘half-hearted’ as opposed to ‘whole-hearted’? (see also Knight 1992). Further, as Stengel himself points out, the definition may not do justice to what has become ‘a very common and varied behaviour pattern’ (1970: 77). Nevertheless, it provides an important insight into the kinds of criteria that should be met in order for an act to count as suicide. One such criterion is that of intention — specifically, the intention to end one’s life (Margolis 1975, reprinted in Beauchamp & Perlin 1978: 95). As Beauchamp points out (1980: 70), central to what is called the ‘prevailing definition’ of suicide is the following premise: ‘Suicide occurs if and only if there is an intentional termination of one’s own life.’

Beauchamp suggests that other criteria should be met in order for an act to count as suicide, including the following:

1. death is chosen voluntarily (that is, is free of coercive or manipulative influences)

2. an active means of death is chosen

3. death is caused by the person desiring death (one dies by ‘one’s own hand’)

4. death is self-regarding (rather than altruistic or other-regarding)

5. the person seeking death does not have a fatal or terminal illness.

(Beauchamp 1980: 73–9)

Windt suggests similar criteria of suicide (all of which have been mentioned in the suicide literature). These are:

1. death [must be] caused by the actions or behaviour of the deceased

2. the deceased wanted, desired, or wished death

3. the deceased intended, chose, decided or willed to die

4. the deceased knew that death would result from his [or her] behaviour; and that

5. the deceased was responsible for his [or her] own death.

(Windt 1980: 41, tabulations added)

At first glance, these and similar criteria of suicide appear helpful. On closer analysis, however, a number of problems quickly become apparent — not least the problem of so-called ‘exceptional cases’, and whether the criteria listed are relevant to or can be applied appropriately and meaningfully to these cases. Consider, for example, the cases of people engaging in dangerous and potentially life-threatening (‘suicidal’) sports (for instance, bungee jumping, mountain climbing, racing car driving, hang gliding); dangerous work activities (being a member of a bomb disposal squad or a combat soldier are paradigm examples here); or other life-threatening activities such as cigarette smoking, eating and drinking excessively, illicit drug taking, and so on. In all these cases, it is probably true that the people concerned: chose the activities in question; were aware of the potential threats the activities posed to their lives and wellbeing; voluntarily engaged in the activities chosen; and, were they to die as a result of engaging in these activities, were ‘responsible for their own deaths’, insofar as they were willing accomplices to the activities and their associated risks. Further, while the people concerned might not have intended their own (accidental) deaths, they nevertheless foresaw their deaths as a possibility associated with the risky activities they had engaged in, and thereby, ipso facto, can be said to have intended their own demise. Given the criteria for suicide outlined above, it seems we are committed to accepting that people who die as a result of their deliberately engaging in dangerous sporting activities, work activities or lifestyles have, in essence, suicided. Yet, this does not seem to accord with our intuitions on the matter — nor does it sit comfortably with what we would perhaps ordinarily regard as suicide. Let us examine another example to see if this will clarify the matter.

In 1982, Barney Clark, aged 62, became the first human being to receive an artificial (mechanical) heart (Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 188; Rachels 1983). Recognising that this medical experiment had the potential to make Mr Clark’s life burdensome, his doctor, Willem Kolff, gave him a key that could be used to turn off the compressor sustaining the artificial heart’s action. Defending his decision to supply this key, Dr Kolff argued that if Mr Clark:

suffers and feels it isn’t worth it any more, he has a key that he can apply … I think it is entirely legitimate that this man whose life has been extended should have the right to cut it off if he doesn’t want it, if life ceases to be enjoyable.

(cited in Beauchamp & Childress 2001: 188)

The conceptual dilemma which arises here is this: if Mr Clark had chosen to use the key he had been given, and had turned off the compressor driving his artificial heart, which of the following statements would have been the most accurate description of his action and the cause of his death:

1. forgoing extraordinary means of life-sustaining treatment

2. withdrawing from an experiment

3. letting nature take its course

4. natural death

5. euthanasia

6. suicide?

To complicate the issue, as Beauchamp and Childress point out (2001: 188):

If [Clark] had refused to accept the artificial heart in the first place, few would have labelled his act a suicide. His overall condition was extremely poor, the artificial heart was experimental, and no suicidal intention was evident. If, on the other hand, Clark had intentionally shot himself with a gun while on the artificial heart, the act would have been characterised as suicide.

And, to complicate the issue still further, what if Mr Clark had consented to receiving the heart in the belief that the risks associated with the experiment were so great that a hastened death would be assured? Could this be classified as a kind of suicide?

Part of the difficulty in sorting out the conceptual confusion surrounding the development of an adequate definition of and criteria for suicide can be linked to the lingering legacy of varying socio-cultural historical and religious taboos against suicide. Beauchamp and Childress (1989: 223) suggest, for example, that we often shield acts of which we approve (or at least acts of which we do not disapprove) from the stigmatising label of ‘suicide’ — preferring instead to use terms that are more socially acceptable, such as ‘euthanasia’ or ‘withdrawing extraordinary life-saving treatment’, and similar notions. If this is correct, it is ironic, considering that the term ‘suicide’ was first adopted in the 17th century as a more ‘acceptable’ alternative to the then contemporary usages ‘self-murder’ and ‘self-slaughter’, which were regarded by more liberal-minded people of the day as having unacceptably negative connotations (Battin 1982: 22, 58).

In light of these considerations, perhaps an important first step in developing a workable definition of and criteria for suicide is to demystify suicide, and to strip it of the taboos and stigmatisations which still seem to linger around it — and which may encourage people to be less than intellectually honest when speaking of its incidence and cause. A second and related step is to modify the negatively connoted language that tends to be used in referring to and discussing suicide. In this instance, the problem of language is highly significant, and should not be underestimated. As Wennberg explains (1989: 17):

‘suicide’ is not a neutrally descriptive term like ‘cat’, ‘car’, or ‘flower’. Rather, it carries with it a strong negative connotation, especially when it is part of the phrase ‘commit suicide’. For one typically does not commit X where X is either something approved or something of neutral standing (cf. ‘commit murder’, ‘commit a felony’, ‘commit a crime’, ‘commit adultery’, ‘commit a sin’, ‘commit treason’, ‘commit a faux pas’, etc.).

The lesson here is important: the use of the phrase ‘committed suicide’ (as opposed to using the phrase ‘completed suicide’ or the term suicided) is misleading and unhelpful — not least because it seems to imply the commission of a crime, or even a sin, when clearly there has been none.

A third and final step towards developing a working definition of and criteria for suicide is to reinstate the authority of our own ordinary commonsense experience of the world, and our collective experience-based knowledge of what is and is not an act of suicide or attempted suicide. One reason for this is that, in the ultimate analysis, the distinction between suicide and other types of death (e.g. euthanasia) may rest not on sophisticated philosophical criteria, but on our fine intuitions informed by life experience. I suspect, however, that in the main, conceptual clarity in regard to what is and is not an act of suicide will rest on something far more substantial than abstract criteria or even well-informed intuition. Rather, the matter will be decided by appealing to:

1. the known intentions and motivations of the person who has died (for instance, whether the death was pursued as ‘an alleged solution for the ills of dying’ [euthanasia], or pursued as an ‘alleged’ cure for the ills of living [suicide] [Donnelly 1990: 9])

2. the context in which the person died

3. whether the person who died genuinely believed there was no other alternative besides death in order to alleviate his or her suffering, or to transcend the life circumstances which for him or her had become unbearable.

The problem remains, however, that ascertaining these things may be just as difficult as establishing reliable criteria for suicide. Nevertheless, it is important that suicide be defined. One reason for this is that without an adequate definition of suicide it will remain extremely difficult to assess accurately the incidence, cause and appropriate means of preventing suicide. It will also be difficult to eradicate the spurious distinction which is sometimes drawn between ‘genuine’ and ‘non-genuine’ suicide attempts, with the tragic consequence that some who are suffering and needing help will be dismissed as malingerers, and worse, as not suffering or needing help at all.

(To advance understanding on the raw suffering and despair that suicidal people experience, see in particular: Williams [1997] Cry of pain: understanding suicide and self-harm; Heckler [1994] Waking up alive: the descent to suicide and return to life; and Knight’s [1992] discussion on the suffering of suicide.)

Finally, without an adequate definition of suicide it will make it difficult to engage in substantive moral debate on the ethical aspects of suicide, and to respond effectively and appropriately to the many moral problems raised by the suicide question, some of which are considered below.

Before continuing, however, a brief clarification is required on the working definitions of the terms ‘suicide’ and ‘parasuicide’ to be used in the remainder of this chapter, and on the distinction which might otherwise be drawn between ‘suicide’ (as presently being considered in this chapter) and ‘euthanasia’ (as considered in the previous chapter).

Although there is no universally agreed definition of suicide, and, as shown, the term itself is difficult to define (see also Soubrier 1993), suicide is generally recognised as being one of the five medical–legal classifications of modes of death, which are taken to include (in addition to suicidal death): accidental, natural, homicidal and undetermined death (Colt 1991: 263–4). Furthermore, while acknowledging the many difficulties associated with formulating a precise and universally agreed definition of suicide, there is a strong sense in which suicide (at least in the Western world) can be meaningfully understood as:

a conscious act of self-induced annihilation, best understood as a multidimensional malaise in a needful individual who defines an issue for which the suicide is perceived as the best solution.

(Shneidman 1985: 203)

A more elaborate explication of this view is as follows (advanced by Edwin Shneidman [1993: 3], popularly regarded as the ‘father’ of contemporary suicidology [Leenaars 1993: xi]):

My principal assertion about suicide has two branches. The first is that suicide is a multifaceted event and that biological, cultural, sociological, interpersonal, intrapsychic, logical, conscious and unconscious, and philosophical elements are present, in various degrees, in each suicide event.

The second branch of my assertion is that, in the distillation of each suicide event, its essential element is a psychological one; that is to say, each suicidal drama occurs in the mind of a unique individual. Suicide is purposive. Its purpose is to respond to or redress certain psychological needs. There are many pointless deaths but there are no needless suicides. Suicide is a concatenated, complicated, multidimensional, conscious and unconscious ‘choice’ of the best possible practical solution to a perceived problem, dilemma, impasse, crisis or desperation.

Parasuicide (a term which came into usage in the late 1960s in an attempt to overcome the confusion associated with using the term ‘attempted suicide’ [see Kreitman 1969; Williams 1997: 68]) can, in turn, be defined as:

An act with non-fatal outcome, in which an individual deliberately initiates a non-habitual behaviour that, without intervention from others, will cause self-harm, or deliberately ingests a substance in excess of the prescribed or generally recognised therapeutic dosage, and which is aimed at realising changes which the subject desired via the actual or expected physical consequences.

(Williams 1997: 69)

For the purposes of this discussion, both suicide and parasuicide are taken here as being the ‘unequivocal expression of raw suffering’ (and it might be added ‘psychache’ [Shneidman 1993]) of individuals — a suffering from which, for a variety of reasons (not always known or understood by others), these individuals have not been able to secure relief (Heckler 1994: xxiv). Suicide ideation (suicidal thoughts) and suicidal behaviour are also taken here as being ‘the result of extreme and unusual human predicaments’ which require our deepest and most empathic understanding (Heckler 1994: xxv), not our derision as has so frequently been the case (see Bailey 1994, 1998).

Suicide, as being considered in this chapter, is taken here as referring to a different kind of death that might otherwise be brought about by voluntary active euthanasia or physician-assisted suicide. While euthanasia, physician-assisted suicide and ‘unassisted’ suicide (the topic of this chapter) share many features in common, as we will go on to see, there are also some significant differences between them. One such difference was captured recently by the following insightful comments made in class by an on-site overseas student undertaking a Bachelor of Nursing (post-registration) degree at RMIT University in Melbourne, Australia:

As I see it, in the case of euthanasia/assisted suicide, the person wants to live, but cannot (and it is too hard to die); whereas in the case of ‘suicide proper’, the person can live, yet does not want to (it is too hard to live).

(Su Chia Hsian, personal communication)

Other differences will become more apparent as the discussion in this chapter is advanced. One key difference, however, warrants mention here: whereas euthanasia and physician-assisted suicide tends to be conducted in the context of a breakdown in physical health and wellbeing, suicide (as being considered here) tends to occur in the context of a breakdown in mental health and wellbeing; that is, it is linked in important ways to a lethal combination of the psychogenic distress states of depression, hopelessness, despair and apathy (Colt 1991; Firestone 1997; Heckler 1994; Hendin 1998; Leenaars 1993; Lester & Tallmer 1994; Remafedi 1994a; Shneidman 1993; Williams 1997).

S uicide: some moral considerations

As discussed earlier under the subheading ‘Socio-cultural attitudes to suicide: a brief historical overview’, the Judaeo–Christian traditions have, for the most part, regarded suicide as the gravest sin imaginable, and as constituting the most serious violation of one’s duties to oneself, to others and to God. These views have been extremely influential and, not surprisingly, the subject of much philosophical debate. Today, however, as Knight (1992: 262) correctly points out, ‘religiously speaking, the notion of suicide as an unforgivable sin has few, if any, defenders in contemporary moral philosophy’. Further, unlike the days when religious prohibition saw suicide condemned as a grossly immoral act, it is difficult today to find tenable moral arguments against the suicide of people who are able to choose autonomously to end their own lives (Knight 1992: 262). Nevertheless, a number of troubling questions remain about the ethics or morality of suicide, such as: Is there a right to suicide? If so, what conditions must be satisfied before this right can be claimed? What are the obligations of others in regard to those contemplating or attempting suicide? Is there a duty to prevent suicide? If so, under what conditions should a suicide be prevented? It is to briefly answering these questions that the remainder of this discussion now turns.

A utonomy and the right to suicide

Fundamental to Western moral thinking is the principle of autonomy. As discussed in Chapter 3 of this book, the moral principle of autonomy prescribes that a person’s considered choices should be respected — even if others disagree with them or regard them as foolish — provided they do not interfere with or harm the significant moral interests of others. If we accept this principle, we must also accept that people who choose autonomously to suicide are entitled to have their choices respected, and further, that it would be morally indefensible to prevent these people from exercising their choices. By this view, as Beauchamp explains (1980: 100):

If people are autonomous, then they have the right to be left alone and to do with their lives as they wish, so long as they are sufficiently free of responsibilities to others. From this perspective, the intervention in the life of a suicide is simply an unjust deprivation of liberty.

Jonathan Glover argues along similar lines (1977: 171), explaining that once it is admitted that suicide need not always be regarded as an ‘irrational symptom of mental disturbance’ (see also Wennberg 1989: 39), then:

[it] is a matter for each person’s free choice: other people should have nothing to say about it, and the question for someone contemplating it is simply one of whether his [or her] future life will be worth living.

It is far from certain, however, that people contemplating or attempting suicide are, in fact, entitled to be ‘left alone and to do with their lives as they wish’ (Beauchamp 1980: 100), or that ‘other people should have nothing to say about it’ (Glover 1977: 171). There are a number of reasons for this. First, an act of suicide is never without moral consequences: not only does it have an impact on the significant moral interests of the person suiciding, but it can significantly affect the important moral interests of others (as stated earlier, between six and ten people can be directly and significantly affected by the suicide of another). As experience tells us, suicide can shatter, injure and destroy the lives of other people; it can also cause substantial loss to society (see also Battin 1982, 1996). Where suicides do affect the significant moral interests of others, there are at least prima-facie grounds for justifying paternalistic intervention to prevent those suicides occurring. As well as this, where other people’s significant moral interests are at stake, there may even be an obligation on the part of people contemplating suicide not to proceed with planned actions aimed at ending their own lives (Brandt 1978: 128) — although it is an open question just how realistic this demand is in the case of people suffering severe psychological distress.

In the light of these circumstances, it is evident that claims to autonomy alone are not sufficient to justify an unequivocal acceptance of a person’s decision to suicide, or to justify non-intervention or ‘non-postvention’ (counselling and therapy after a suicide attempt [Battin 1982: 16]) in the case of contemplated or attempted suicide. Of course, there is always the possibility that the concerns or interests of others may not be strong enough to override a person’s autonomous choice to suicide. This, however, is something which must be determined by careful evaluation and a ‘balancing of considerations’ of all the moral interests involved (Beauchamp & Perlin 1978: 91), not just by an uncritical deontological acceptance of the moral principle of autonomy. Such a calculation might even show that a contemplated suicide, once carried out, should indeed be permitted in the interests of others. For example, the suicide of a long-term abusing spouse might be shown to be more permissible morally than the homicide of his abused wife and children. Whether this would really be a morally desirable outcome, however, is a contentious point and unfortunately one which is beyond the scope of this work to address.

A second reason why it is not clear that people contemplating or attempting suicide should not have their choices interfered with is that the quality of the autonomy behind the choice may not be optimal. As discussed in Chapter 3 of this book, as a concept (to be distinguished here from a principle), autonomy refers to a person’s independent and self-contained ability to decide. At issue in the case of suicide is the question of whether a person contemplating suicide is really capable of making the evaluative, deliberative and reflective choices that are fundamental to a ‘rational’ and autonomous decision to suicide. While it is true that even so-called ‘incompetent’ people are still capable of making self-interested choices (see, e.g. the discussion on competency in Chapter 6 of this book), the extent to which the choices of these people should be respected is not something that can be decided solely on the basis of the demands prescribed by the moral principle of autonomy; there are other moral considerations that need to be taken into account — including the moral demand to prevent otherwise avoidable harm to people, which a suicide death could cause.

The issue of the quality of a suicidal person’s autonomous choice to kill himself or herself is an important one and, even when considered from a clinical as opposed to a philosophical perspective, has an important bearing on deciding the ethical acceptability of paternalistic interventions aimed at preventing people from completing suicide (see also Rudnick 2002).

It has been suggested that depression ‘is a substantial part of the picture of at least 50% of suicides’ (Knight 1992: 249–50; see also Balázs et al 2006). While depression alone may not result in suicide, when it is coupled with abiding and intolerable feelings of hopelessness about the future, despair and apathy, the risk of suicide is extremely high (Firestone 1997; Heckler 1994; Hendin 1998; Hewitt & Edwards 2006; Knight 1992; Kuyken 2004; Williams 1997). Of importance to the discussion at this point is the consideration that feelings of depression, hopelessness, apathy and despair can have a significant and far-reaching impact on a person’s ability to make ‘truly’ autonomous choices. As has long been recognised in the bioethics literature, these feelings can:

▪ restrict people’s abilities to evaluate and calculate correctly the range of possibilities and probabilities available when planning and making judgments about their lives and future prospects (Brandt 1978: 131; Beauchamp 1980: 101)

▪ skew calculations of the probable harms and benefits that may flow from suicide (as Beauchamp [1980: 101] points out, ‘without depression, persons might make quite different calculations even when their situation is dire’)

▪ result in suicidal people overestimating the magnitude and insolubility of their problems (Knight 1992: 266)

▪ result in impulsive and imprudent choices that might otherwise not have been made (Heyd & Bloch 1981: 187).

In short, feelings of depression, hopelessness, apathy and despair can undermine in very significant ways a person’s ability to make sound autonomous choices. The question remains, however, of whether these feelings and a possible associated diminution in the ability to make sound autonomous choices are of a nature that justifies paternalistic intervention to prevent a person completing suicide — including using invasive procedures to resuscitate someone who has attempted suicide. Or would such intervention — no matter how benevolent — still constitute an unacceptable violation of the moral principle of autonomy?

The short answer to these questions is that intervention may not only be justified, but may even be required, in the interests of both promoting a person’s autonomy and saving a worthwhile life. On this point, Jonathan Glover explains (1977: 176–7):

Where we think someone bent on suicide has a life worth living, it is always legitimate to reason with him [or her] and to try and persuade him [or her] to stand back and think again. There is no case against reasoning, as it in no way encroaches on the person’s autonomy. There is a strong case in its favour, as where it succeeds it will prevent the loss of a worthwhile life. (If the person’s life turns out not to be worthwhile, he [or she] can always change his [or her] mind again.) And if persuasion fails, the outcome is no worse than it would otherwise have been.

Glover goes on to contend that where suicidal tendencies are the product of temporary depressive mood-swings — for instance, where the person ‘alternates between very much wanting to go on living and moods of suicidal depression’ — then intervention aimed at overriding a decision to suicide ‘is less disrespectful of autonomy than overriding a preference that plays a stable role in a person’s outlook’ (p 178). If, for example, a person repeatedly and persistently attempts suicide, and the underlying preference (that is, to die) informing these attempts remains constant, then the onus is on would-be ‘rescuers’ or interveners to reconsider their own judgments about whether the life of the person attempting suicide is, in fact, worthwhile and worth living, or whether they have been mistaken in their views. Unpleasant as it may be, the demand in the latter instance may be an overriding one in favour of not intervening to save the person’s life (Glover 1977: 178). Before this position is accepted, however, there are at least prima-facie grounds for asserting that the following five conditions must be met:

1. that the decision to suicide is based on a realistic assessment of the life-circumstances or situation at hand (Motto 1983: 443–6; Knight 1992: 254)

2. that the person contemplating suicide has made an ‘exhaustive examination’ of all available options and has taken into account the ‘various possible “errors” and [made] appropriate rectifications of his [or her] initial evaluation’ (Brandt 1978: 132)

3. that the thought processes used in reaching the decision to suicide have not been impaired by severe emotional distress, feelings of hopelessness and despair, mental illness or the adverse side effects of drugs (Knight 1992: 254)

4. that the degree of ambivalence between wanting to live and wanting to die is minimal (Motto 1983: 443–6; Glover 1977: 178; Donnelly 1990: 8)

5. that the desire and motivation to suicide is of a nature that ‘uninvolved observers from their community or social group [would find] understandable’ (Knight 1992: 254).

While the satisfaction of these criteria may not always result in the prevention of morally undesirable consequences in situations involving people wanting to suicide, it may nevertheless result in more appropriate assessments of when it is right and when it is not right to paternalistically override a person’s autonomous decision to suicide.

One problem which emerges here, however, is that, even if these criteria are not satisfied, does that necessarily justify paternalistic intervention to prevent a person from completing a suicide? What if the suicidal person in question is in a state of intolerable suffering as in the Chabot case and the unnamed man in the Swiss case discussed in the previous chapter? Here the additional question arises: Can those who are suffering intolerably and intractably (whether on account of physical or mental illness or some other state of physical or psychogenic distress) be expected decently to go on living? Or should people in these situations be released from the ‘obligation to live’ — if, indeed, it is an obligation — irrespective of their ability to decide autonomously what is in their own best interests? Are others entitled morally to force a person to go on living a life characterised by excruciating feelings of depression, hopelessness, apathy, despair and a sense that life has lost all meaning and purpose?

It is not unreasonable to hold that a person in this state would prefer death to life. As Glover points out (1977: 174):

Most of us prefer to be anaesthetised for a painful operation. If most of my life were to be on that level, I might opt for a permanent anaesthesia, or death.