Peritoneal Lavage (Perform)

Peritoneal Lavage (Perform)

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of the anatomy and physiology of the abdomen is important to avoid unexpected outcomes.

• The intestines and the bladder lie immediately beneath the abdominal surface. In children, the bladder is an abdominal organ. In adults, a full bladder is raised out of the pelvis.

• The cecum is relatively fixed and is much less mobile than the sigmoid colon; therefore, bowel perforations are more frequent in the right lower quadrant than in the left.

• A distended stomach can extend to the anterior abdominal wall.

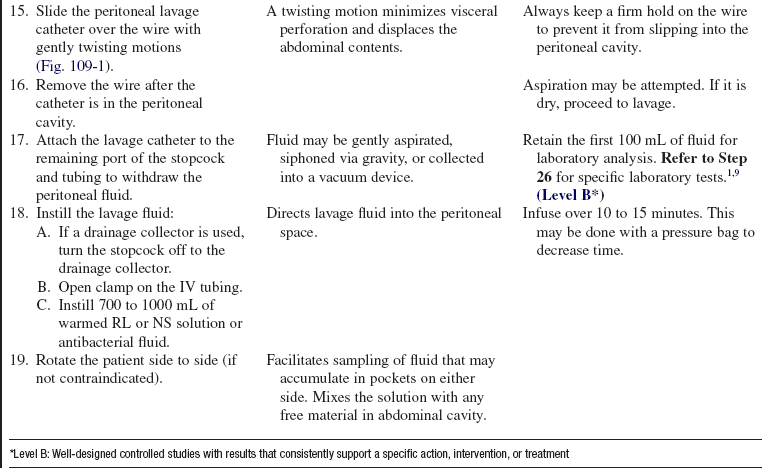

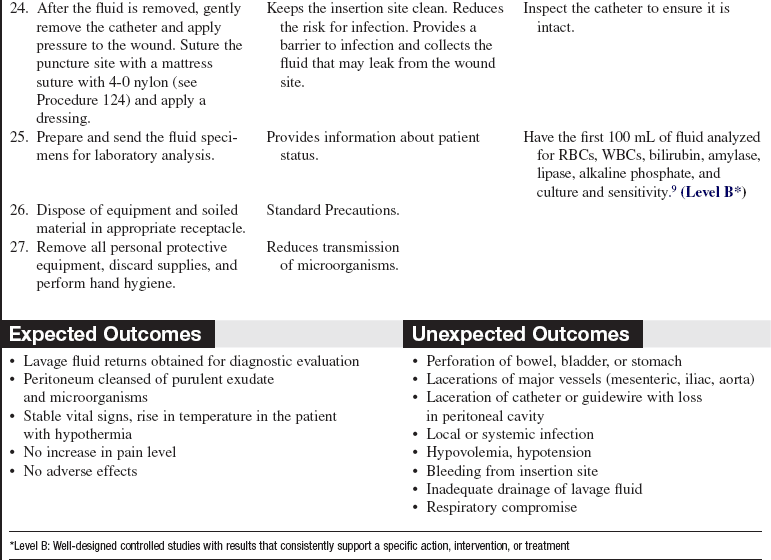

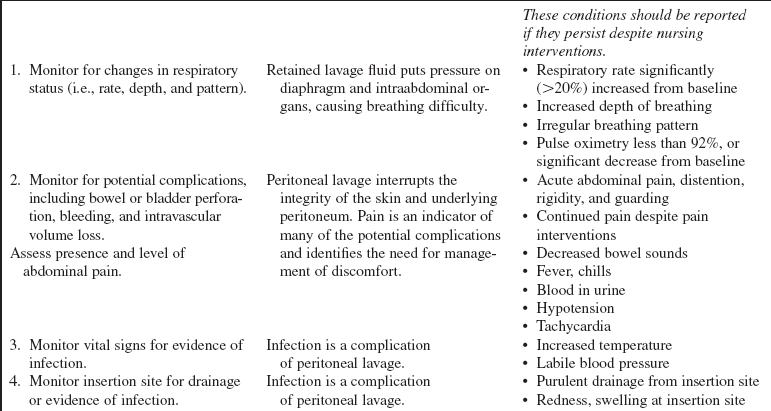

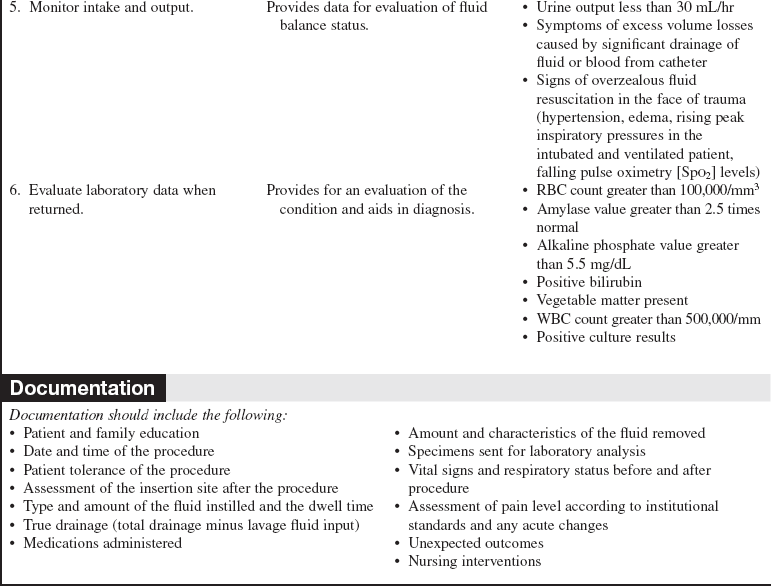

• Peritoneal fluid is normally straw-colored, serous fluid secreted by the cells of the peritoneum. Grossly bloody fluid, a red blood cell (RBC) count of greater than 100,000/mm3,2,5,9 or the presence of bacteria or bile in the return fluid in the abdomen is abnormal. A white blood cell (WBC) count greater than 500,000/mm and the presence of bile or amylase in the lavage fluid are parameters, in addition to the RBC count, that can lead to operative intervention.2,5,9

• Diagnostic peritoneal lavage is a highly sensitive tool for diagnosis of visceral injuries in the abdominal cavity.1,5,8

• Diagnostic peritoneal lavage is used after blunt abdominal trauma or in trauma patients who have head injuries, are unconscious, or have preexisting paraplegia to determine the presence of the following2:

Hemoperitoneum (blood in lavage returns)

Hemoperitoneum (blood in lavage returns)

Organ injury (intestinal enzymes or microorganisms in lavage returns)

Organ injury (intestinal enzymes or microorganisms in lavage returns)

• Therapeutic lavage is used to:

Irrigate and cleanse purulent exudate in patients with peritonitis or intraabdominal abscess

Irrigate and cleanse purulent exudate in patients with peritonitis or intraabdominal abscess

Warm the abdominal cavity in patients with hypothermia

Warm the abdominal cavity in patients with hypothermia

Remove unwanted or toxic chemicals through peritoneal dialysis

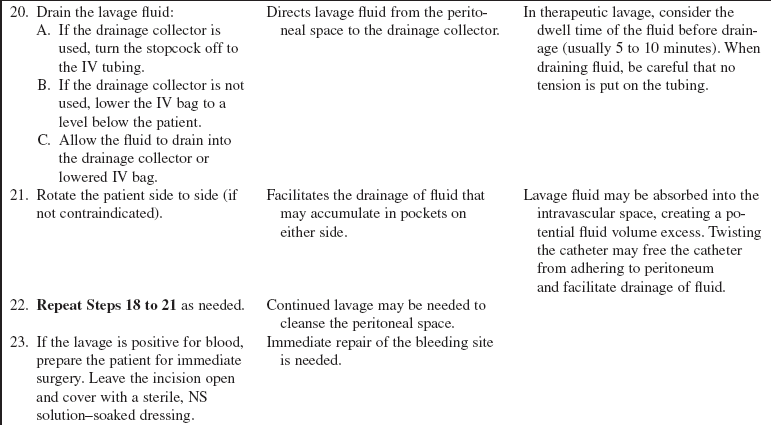

Remove unwanted or toxic chemicals through peritoneal dialysis

• For trauma patients with stab wounds and gunshot wounds to the lower chest or anterior abdomen, diagnostic peritoneal lavage is controversial; most trauma centers operate on patients with gunshot wound injuries to the lower chest or anterior abdomen.1

• Diagnostic peritoneal lavage can be used as a tool in patients with hypotension of uncertain etiology in the presence of trauma.6

• Diagnostic peritoneal lavage is not necessary if abdominal surgery is already indicated.7,9

• Because it is an invasive procedure, diagnostic peritoneal lavage does have a small risk of visceral injury (0.6%).5

• Diagnostic peritoneal lavage is 95% sensitive and 99% specific for intraperitoneal blood; however, it cannot exclude retroperitoneal hemorrhage, disruption of the diaphragm, or hollow viscus perforation.5,7

• Computed tomography (CT) scan frequently is used in trauma patients with hemodynamically stable conditions as the diagnostic procedure of choice.5 Also, abdominal ultrasound scan and focused abdominal sonography in trauma (FAST) have been increasingly used to screen blunt abdominal trauma cases for hemoperitoneum.9

• In patients with hemodynamically unstable conditions, diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) may be preferred because of its high sensitivity.1,2,5,9 DPL is quick, inexpensive, safe, and highly sensitive to the presence of blood in the peritoneal cavity.5 Patients with hemodynamically unstable conditions may also go directly to the operating room (OR) for laparotomy.

• Complementary CT scan and DPL decreases nontherapeutic laparotomy rates and allows nonoperative management of those patients with solid-organ injury.9

• Peritoneal lavage is absolutely contraindicated in an acute abdomen that needs immediate surgery as indicated by free air on radiography or penetrating abdominal trauma.

• Relative contraindications for DPL include the following5,6:

Previous abdominal surgery, especially pelvic surgery

Previous abdominal surgery, especially pelvic surgery

Distended bladder that cannot be emptied with a Foley catheter

Distended bladder that cannot be emptied with a Foley catheter

Obvious infection at intended site of insertion (cellulitis or abscess)

Obvious infection at intended site of insertion (cellulitis or abscess)

• Use caution when performing DPL in patients with suspected pelvic fractures (may use a supraumbilical site) because of false-positive results7; if DPL is performed in pregnant patients of more than 12 weeks’ gestation, use an open technique, superior to the uterus.7

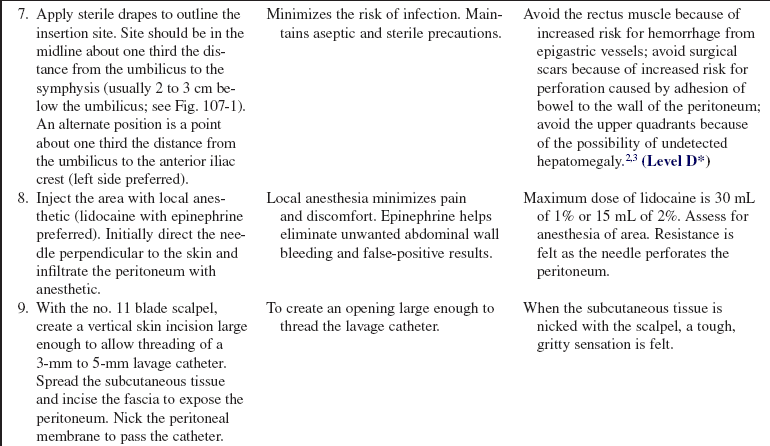

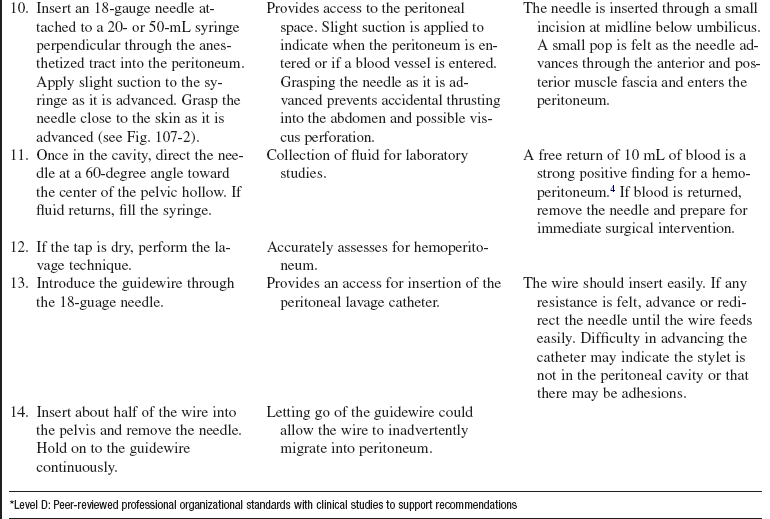

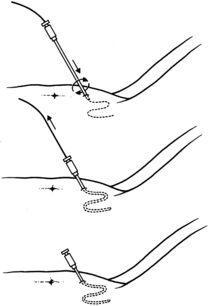

• Insertion site should be midline, one third the distance from the umbilicus to the symphysis, or 2 to 3 cm below the umbilicus (see Fig. 107-1). An alternate position is a point one third the distance from the umbilicus to the anterior iliac crest (left side preferred).

• Ultrasound scan can be used before peritoneal lavage to locate fluid and during the procedure to guide insertion of the catheter.9

EQUIPMENT

• Commercially prepared kit or the following:

Personal protective equipment, including sterile gloves, mask, goggles, and gown

Personal protective equipment, including sterile gloves, mask, goggles, and gown

Skin cleansing solution (chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine)

Skin cleansing solution (chlorhexidine or povidone-iodine)

Sterile towels or sterile drape

Sterile towels or sterile drape

Razor to shave area, if necessary

Razor to shave area, if necessary

Local anesthetic for injection: 1% or 2% lidocaine with epinephrine

Local anesthetic for injection: 1% or 2% lidocaine with epinephrine

5- or 10-mL syringe with 25- or 27-gauge needle for anesthetic

5- or 10-mL syringe with 25- or 27-gauge needle for anesthetic

Scalpel and no. 11 knife blade

Scalpel and no. 11 knife blade

Trocar with stylet; needle (16-, 18-, or 20-gauge) or angiocatheter; depending on abdominal wall thickness may use guidewire with floppy tip and 9 to 18 Fr peritoneal lavage catheter

Trocar with stylet; needle (16-, 18-, or 20-gauge) or angiocatheter; depending on abdominal wall thickness may use guidewire with floppy tip and 9 to 18 Fr peritoneal lavage catheter

20-mL syringe for diagnostic tap

20-mL syringe for diagnostic tap

Sterile intravenous (IV) tubing (without valves) with appropriate sterile connectors for lavage catheter and IV bags

Sterile intravenous (IV) tubing (without valves) with appropriate sterile connectors for lavage catheter and IV bags

Warmed Ringer’s lactate (RL), normal saline (NS), or antibiotic solution for infusion into abdomen

Warmed Ringer’s lactate (RL), normal saline (NS), or antibiotic solution for infusion into abdomen

Three-way stopcock for therapeutic lavage

Three-way stopcock for therapeutic lavage

Nylon skin suture material on cutting needle (4-0 or 5-0) and needle holder

Nylon skin suture material on cutting needle (4-0 or 5-0) and needle holder

Four to six sterile 4 × 4 gauze pads

Four to six sterile 4 × 4 gauze pads

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the indications, the procedure, and the risks to the patient and family.  Rationale: Explanation may decrease patient anxiety and may encourage patient and family cooperation and understanding of procedure.

Rationale: Explanation may decrease patient anxiety and may encourage patient and family cooperation and understanding of procedure.

• Explain the patient’s role in assisting with the procedure and postprocedure care.  Rationale: Patient cooperation during and after the procedure is elicited.

Rationale: Patient cooperation during and after the procedure is elicited.

• Explain the signs and symptoms to report, such as fever, abdominal pain, decreased urine output, bleeding, and leakage of fluid from wound site.  Rationale: Unexpected outcomes may not manifest themselves for a period of time after the procedure.

Rationale: Unexpected outcomes may not manifest themselves for a period of time after the procedure.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Obtain the medical history and a review of systems to identify abdominal injury, peritonitis, intraabdominal abscess, or pregnancy.  Rationale: Certain conditions of the gastrointestinal tract may be diagnosed and treated with peritoneal lavage. Contraindications to peritoneal lavage may be identified.6

Rationale: Certain conditions of the gastrointestinal tract may be diagnosed and treated with peritoneal lavage. Contraindications to peritoneal lavage may be identified.6

• Identify the presence of any allergies to medication or other substances.  Rationale: Patients may have allergies to skin preparations or anesthetics used before the invasive procedure is performed. This identification assists the practitioner in choosing the most appropriate skin preparation and anesthetic.

Rationale: Patients may have allergies to skin preparations or anesthetics used before the invasive procedure is performed. This identification assists the practitioner in choosing the most appropriate skin preparation and anesthetic.

• Assess for bowel or bladder distention.  Rationale: Distention increases the risk for bowel or bladder perforation during the procedure.7

Rationale: Distention increases the risk for bowel or bladder perforation during the procedure.7

• Coagulation studies (i.e., prothrombin time [PT], partial thromboplastin time [PTT], and platelets).  Rationale: Abnormal clotting studies may increase the risk for bleeding during and after the procedure. Therapy may be necessary to correct clotting abnormalities before the procedure is performed.

Rationale: Abnormal clotting studies may increase the risk for bleeding during and after the procedure. Therapy may be necessary to correct clotting abnormalities before the procedure is performed.

• Obtain plain radiographs of the abdomen and upright abdominal films if possible (before the procedure).  Rationale: Air is introduced during the procedure and may confound the diagnosis later.7

Rationale: Air is introduced during the procedure and may confound the diagnosis later.7

• Obtain baseline vital signs and pain assessment according to institutional standard.  Rationale: Practitioner can identify intraprocedure or postprocedure changes that may be indicative of complications.

Rationale: Practitioner can identify intraprocedure or postprocedure changes that may be indicative of complications.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Obtain signed informed consent from the patient or decision maker, if possible. In a trauma situation or unresponsive patient, this may be implied consent.  Rationale: Peritoneal lavage is an invasive procedure that requires a signed consent form.

Rationale: Peritoneal lavage is an invasive procedure that requires a signed consent form.

• Have patient void or insert a urinary drainage catheter.  Rationale: A distended bladder increases the risk for bladder perforation during the procedure.7

Rationale: A distended bladder increases the risk for bladder perforation during the procedure.7

• Insert a nasogastric tube unless contraindicated (e.g., in significant facial trauma) and attach to low intermittent suction.  Rationale: A distended stomach increases the risk for perforation during the procedure.6

Rationale: A distended stomach increases the risk for perforation during the procedure.6

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the physician or advanced practice nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the physician or advanced practice nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Check that all relevant documents and studies are available before starting the procedure.  Rationale: This measure ensures that the correct patient receives the correct procedure.

Rationale: This measure ensures that the correct patient receives the correct procedure.

• Place the patient in the supine position (may tilt to side of collection slightly for improved fluid positioning).  Rationale: Fluid accumulates in the dependent areas.

Rationale: Fluid accumulates in the dependent areas.

• Examine abdomen for landmarks and mark appropriately. Shave area, if necessary.  Rationale: Correct placement of catheter for peritoneal lavage minimizes complications.

Rationale: Correct placement of catheter for peritoneal lavage minimizes complications.

• For the patient with pain or agitation who is unable to cooperate with the procedure, consider analgesia or sedation. If sedation is needed for the procedure, institution-specific moderate sedation monitoring should be performed.  Rationale: Analgesia and sedation provide for patient comfort and safety during procedure.

Rationale: Analgesia and sedation provide for patient comfort and safety during procedure.

• If the patient has altered mental status, soft wrist restraints may be needed.  Rationale: The patient must not move his or her hands into the sterile field once it has been established.

Rationale: The patient must not move his or her hands into the sterile field once it has been established.

References

![]() 1. Brakenridge, SC, et al. Detection of intra-abdominal injury using diagnostic peritoneal lavage after shotgun wound to the abdomen. J Trauma. 2003; 54:329–331.

1. Brakenridge, SC, et al. Detection of intra-abdominal injury using diagnostic peritoneal lavage after shotgun wound to the abdomen. J Trauma. 2003; 54:329–331.

2. Crandall, M, West, MA, Evaluation of the abdomen in the critically ill patient. opening the black box. Curr Opin Crit Care 2006; 12:333–339.

3. Ferri, FF. Paracentesis. In Ferri FF, ed. : Practical guide to the care of the medical patient, ed 7, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2007.

4. Griffin, XL, Pullinger, R. Are diagnostic peritoneal lavage or focused abdominal sonography for trauma safe screening interventions for hemodynamically stable patients -after blunt abdominal trauma? A review of the literature. J Trauma. 2007; 62:779–784.

5. Jansen, JO, Yule, SR, Loudon, MA. Investigation of blunt abdominal trauma. BMJ. 2008; 336:938–942.

Marx, JA. Peritoneal procedures. In: Roberts JR, Hedges JR, eds. Clinical procedures in emergency medicine. ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2004:733–749.

![]() 7. Proehl J, ed.. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Emergency nursing procedures. ed 4. Elsevier, St Louis, 2008.

7. Proehl J, ed.. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Emergency nursing procedures. ed 4. Elsevier, St Louis, 2008.

Sato, T, Hirose, Y, Saito, H, et al, Diagnostic peritoneal -lavage for diagnosing blunt hollow visceral injury. the -accuracy of two different criteria and their combination. Surg Today 2005; 35:935–939.

9. Thacker, LK, Parks, J, Thal, ER, Diagnostic peritoneal -lavage. is 100,000 RBC’s a valid figure for penetrating -abdominal trauma. J Trauma Injury Infect Crit Care 2007; 62:853–857.

Bode, PJ, van Vugt, AB. Ultrasound in the diagnosis of injury. Injury. 1996; 27:379–383.

Brown, MA, et al, Blunt abdominal trauma. screening US in 2,693 patients. Radiology 2001; 218:352–358.

Goletti, O, et al, The role of ultrasonography in blunt abdominal trauma. results in 250 consecutive cases. J Trauma 1994; 36:178–181.

Gonzalez, RP, et al, Complementary roles of diagnostic peritoneal lavage and computed tomography in the evaluation of blunt abdominal trauma. J Trauma . 2001; 51:1128–1134.

Liu, A, Kaufmann, C, Ritchie, R. A computer-based simulator for diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Stud Health Technol Inform. 2001; 81:278–285.

Marx, JA, et al, Limitations of computed tomography in the evaluation of acute abdominal trauma. a prospective comparison with diagnostic peritoneal lavage. J Trauma 1985; 25:933–937.

Maxwell-Armstrong, C, et al, Diagnostic peritoneal lavage analysis. should trauma guidelines be revised. Emerg Med J 2002; 19:524–525.

Root, HD, et al. Diagnostic peritoneal lavage. Surgery. 1965; 57:633–637.