Paracentesis (Assist)

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of anatomy and physiology of the abdomen is important to avoid unexpected outcomes.

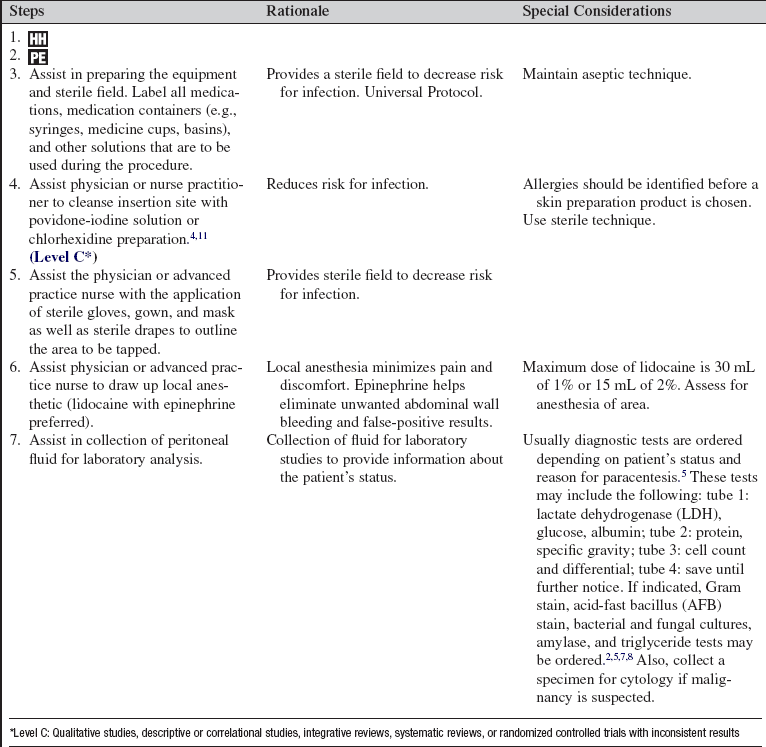

• Intestines and bladder lie immediately beneath the abdominal surface.

• Large volumes of ascitic fluid tend to float the air-filled bowel toward the midline, where it may be easily perforated during the procedure.

• The cecum is relatively fixed and is much less mobile than the sigmoid colon; therefore, bowel perforations are more frequent in the right lower quadrant than in the left.

• Peritoneal fluid is normally straw-colored, serous fluid secreted by the cells of the peritoneum. Grossly bloody fluid in the abdomen is abnormal.

• The peritoneal fluid collected is used to evaluate and diagnose the cause of ascites, acute abdominal conditions such as peritonitis or pancreatitis, and blunt or penetrating trauma to the abdomen.

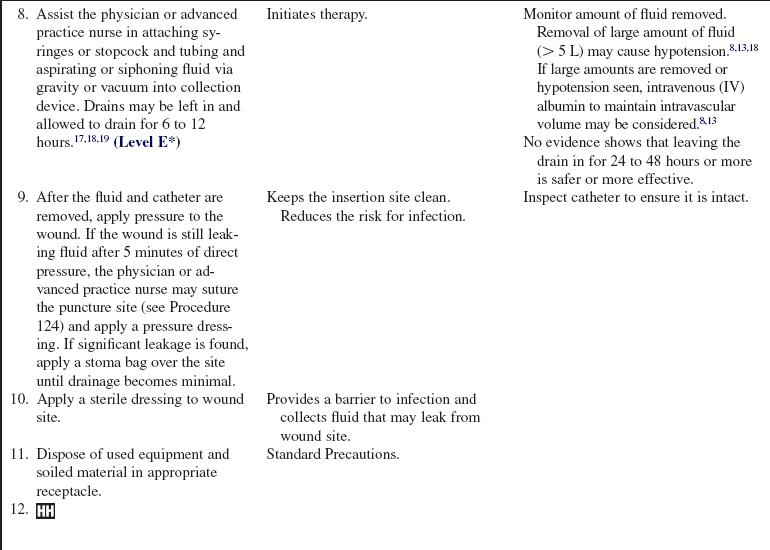

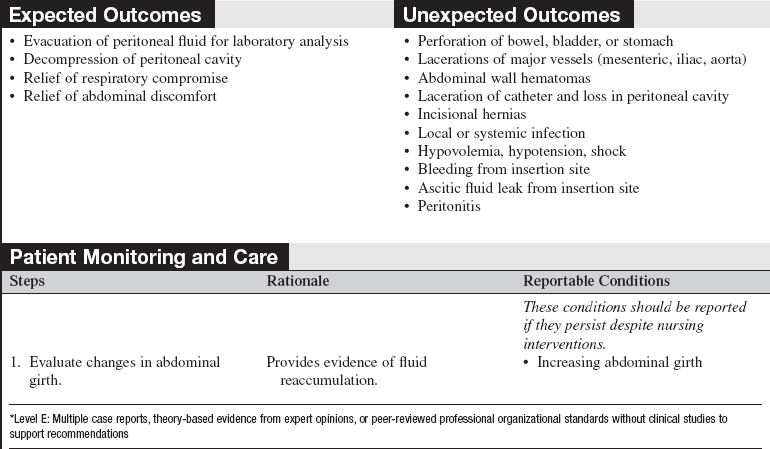

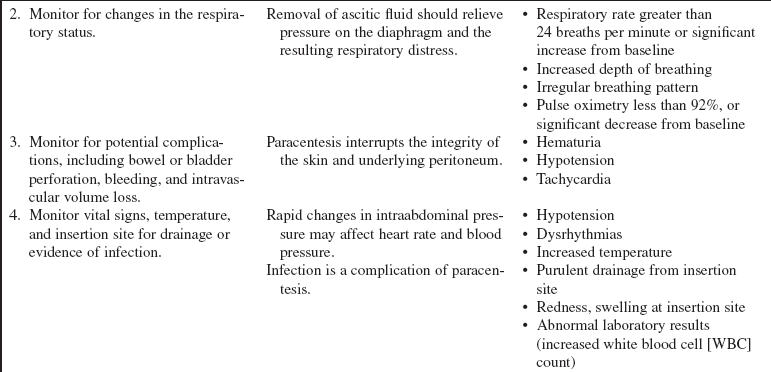

• Therapeutic paracentesis is used to reduce intraabdominal and diaphragmatic pressures to relieve dyspnea and respiratory compromise and to prevent hernia formation and diaphragmatic rupture.12,15,16,19 These complications are seen in those patients with tense, refractory ascites with failed medical interventions, such as sodium restriction and diuresis.5,15,19

• Ascitic fluid is produced as a result of a variety of conditions.10 These conditions may include interference in venous return because of heart failure, constrictive pericarditis, or tricuspid valve insufficiency; obstruction of flow in the vena cava or portal vein; disturbance in electrolyte balance, such as sodium retention; depletion of plasma proteins because of nephrotic syndrome or starvation; lymphoma, leukemia, or neoplasms that involve the liver or mediastinum; ovarian malignant disease; chronic pancreatitis; or cirrhosis of the liver.

• Analysis of the ascitic fluid can determine the cause of ascites. A serum-to-ascites albumin gradient should be calculated by subtracting the ascitic fluid albumin level from the serum albumin. This calculation differentiates portal hypertensive from nonportal hypertensive ascites.5,7,9,10,14,19

• Paracentesis is contraindicated in patients with an acute abdomen, who need immediate surgery. Coagulopathies and thrombocytopenia are considered relative contraindications. Coagulopathy should preclude paracentesis only in the case of clinically evident fibrinolysis or clinically evident disseminated intravascular coagulation.12,16

• Caution should be used when paracentesis is performed in patients with severe bowel distention, previous abdominal surgery (especially pelvic surgery), pregnancy (use open technique after first trimester), distended bladder that cannot be emptied with a Foley catheter, or obvious infection at intended site of insertion (cellulitis or abscess).

• The insertion site should be midline one third the distance from the umbilicus to the symphysis (2 to 3 cm below the umbilicus; see Fig. 107-1). An alternate position is a point one third the distance from the umbilicus to the anterior iliac crest (left side preferred).5,19

• Ultrasound scan can be used before paracentesis to locate fluid and during the procedure to guide insertion of catheter. Ultrasound scan–guided paracentesis has a higher success rate when compared with procedures performed with the physical examination as the lone assessment tool.8

• Endoscopic transgastric ultrasound scan has also been used in the diagnosis of malignant ascites.12

• A semipermanent catheter or a shunt may be an option for patients with rapidly reaccumulating ascites.13,15,16

• When large-volume paracentesis (>5 L) is performed in patients with cirrhosis and other disorders, the infusion of albumin, 6 to 8 g/L of fluid removed, may prevent the onset of circulatory compromise associated with massive fluid shifting.1,3,6,7,18

EQUIPMENT

• Commercially prepared kit or the following:

Personal protective equipment, including sterile gloves, mask, goggles, and gown

Personal protective equipment, including sterile gloves, mask, goggles, and gown

Skin-cleansing solution (povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine preparation)

Skin-cleansing solution (povidone-iodine or chlorhexidine preparation)

Sterile towels or sterile drape

Sterile towels or sterile drape

Local anesthetic for injection: 1% or 2% lidocaine with epinephrine

Local anesthetic for injection: 1% or 2% lidocaine with epinephrine

5- or 10-mL syringe with 21- or 25-gauge needle for anesthetic

5- or 10-mL syringe with 21- or 25-gauge needle for anesthetic

Trocar with stylet, needle (16-, 18-, or 20-gauge), or angiocatheter, depending on abdominal wall thickness

Trocar with stylet, needle (16-, 18-, or 20-gauge), or angiocatheter, depending on abdominal wall thickness

25- or 27-gauge 1½-inch needle

25- or 27-gauge 1½-inch needle

20- or 22-gauge spinal needles

20- or 22-gauge spinal needles

20-mL syringe for diagnostic tap

20-mL syringe for diagnostic tap

50-mL syringe if using stopcock technique

50-mL syringe if using stopcock technique

Four sterile tubes for specimens

Four sterile tubes for specimens

Scalpel and no. 11 knife blade

Scalpel and no. 11 knife blade

Sterile 1-L collection bottles with connecting tubing

Sterile 1-L collection bottles with connecting tubing

Nylon skin suture material on cutting needle (4-0 or 5-0) and needle holder

Nylon skin suture material on cutting needle (4-0 or 5-0) and needle holder

Mayo scissors and straight scissors

Mayo scissors and straight scissors

Four to six sterile 4 × 4 gauze pads

Four to six sterile 4 × 4 gauze pads

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the indications, procedure, and risks to the patient and family.  Rationale: Explanation may decrease patient anxiety and encourages patient and family cooperation and understanding of the procedure.

Rationale: Explanation may decrease patient anxiety and encourages patient and family cooperation and understanding of the procedure.

• Explain the patient’s role in assisting with the procedure and postprocedure care.  Rationale: Patient cooperation during and after the procedure is elicited.

Rationale: Patient cooperation during and after the procedure is elicited.

• Explain the signs and symptoms to report, such as fever, abdominal pain, decreased urine output, bleeding, and leakage of fluid from surgical wound site.  Rationale: Unexpected outcomes may not manifest themselves for a period of time after the procedure.

Rationale: Unexpected outcomes may not manifest themselves for a period of time after the procedure.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Obtain the medical history and a review of systems for abdominal injury, major gastrointestinal pathology, liver disease, and portal hypertension.  Rationale: Certain conditions of the gastrointestinal tract may be diagnosed and treated with paracentesis. Contraindications to paracentesis may be identified.

Rationale: Certain conditions of the gastrointestinal tract may be diagnosed and treated with paracentesis. Contraindications to paracentesis may be identified.

• Identify the presence of any allergies to medication or other substances.  Rationale: Patients may have allergies to skin preparations or anesthetics used before the invasive procedure is performed. Identification assists the practitioner in choosing the most appropriate skin preparation and anesthetic.

Rationale: Patients may have allergies to skin preparations or anesthetics used before the invasive procedure is performed. Identification assists the practitioner in choosing the most appropriate skin preparation and anesthetic.

• Assess respiratory status (i.e., rate, depth, excursion, gas exchange, and use of accessory muscles).  Rationale: Paracentesis may be indicated to decrease the work of breathing.

Rationale: Paracentesis may be indicated to decrease the work of breathing.

• Obtain baseline vital signs, including heart rate, blood pressure, and pulse oximetry.  Rationale: Hypotension and dysrhythmias may occur with rapid changes in the intraabdominal pressure.

Rationale: Hypotension and dysrhythmias may occur with rapid changes in the intraabdominal pressure.

• Obtain a baseline pain assessment.  Rationale: Changes in the level of pain during or after the procedure may be an indicator of complications.

Rationale: Changes in the level of pain during or after the procedure may be an indicator of complications.

• Obtain baseline fluid and electrolyte status.  Rationale: Removal of peritoneal fluid may cause compartment shifting of intravascular volume, electrolytes, and proteins, leading to a decreased circulating volume.

Rationale: Removal of peritoneal fluid may cause compartment shifting of intravascular volume, electrolytes, and proteins, leading to a decreased circulating volume.

• Assess bowel or bladder distention.  Rationale: Distension increases the risk for bowel or bladder perforation during the procedure.

Rationale: Distension increases the risk for bowel or bladder perforation during the procedure.

• Assess abdominal girth.  Rationale: Information on changes in fluid accumulation within the peritoneal cavity is provided.

Rationale: Information on changes in fluid accumulation within the peritoneal cavity is provided.

• Obtain coagulation study results (i.e., prothrombin time [PT], partial thromboplastin time [PTT], and platelets).  Rationale: Abnormal clotting may increase the risk for bleeding during and after the procedure. Therapy may be necessary to correct clotting abnormalities before the procedure.2

Rationale: Abnormal clotting may increase the risk for bleeding during and after the procedure. Therapy may be necessary to correct clotting abnormalities before the procedure.2

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient understands preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Ensure that a written informed consent form has been obtained by the practitioner performing the procedure. The assisting practitioner may be a witness to the signing of the consent if needed.  Rationale: Paracentesis is an invasive procedure and requires a signed informed consent form.

Rationale: Paracentesis is an invasive procedure and requires a signed informed consent form.

• Decompress the bladder either by having the patient void or by inserting a Foley catheter.  Rationale: A distended bladder increases the risk for bladder perforation during the procedure.

Rationale: A distended bladder increases the risk for bladder perforation during the procedure.

• The physician or advanced practice nurse orders plain and upright radiographs of the abdomen before the procedure is performed.  Rationale: Air is introduced during the procedure and may confuse the diagnosis later.

Rationale: Air is introduced during the procedure and may confuse the diagnosis later.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out with the physician or advanced practice nurse, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Check that all relevant documents and studies are available before the procedure is started.  Rationale: This measure ensures that the correct patient receives the correct procedure.

Rationale: This measure ensures that the correct patient receives the correct procedure.

• Place the patient in the supine position (may tilt to side of collection slightly for improved fluid positioning).  Rationale: Fluid accumulates in the dependent areas.

Rationale: Fluid accumulates in the dependent areas.

• The physician or advanced practice nurse will examine the abdomen for areas of shifting dullness, find landmarks, and mark appropriately.  Rationale: Shifting dullness indicates fluid.

Rationale: Shifting dullness indicates fluid.

• If the patient has altered mental status, soft wrist restraints may be needed.  Rationale: The patient must not move his or her hands into the sterile field once it has been established.

Rationale: The patient must not move his or her hands into the sterile field once it has been established.

References

1. Arora, G, Keeffe, EB. Management of chronic liver failure until liver transplantation. Med Clin North Am. 2008; 92(4):839–860.

2. Dib, N, Oberti, F, Cales, P, Current management of the complications of portal hypertension. variceal bleeding and ascites. Can Med Assoc J. 2006; 174(10):1433–1443.

3. Dong, MH, Saab, S. Complications of cirrhosis. Disease A-Month. 2008; 54(7):445–456.

4. Edmiston, CE, Seabrook, GR, Johnson, CP, et al. Comparative of a new and innovative 2% chlorhexidine gluconate-impregnated cloth with 4% chlorhexidine gluconate as topical antiseptic for preparation of the skin prior to surgery. Am J Infect Control. 2007; 35(2):89–96.

5. Ferri, FF. Paracentesis. In Ferri F, ed. : Practical guide to the care of the medical patient, ed 7, Philadelphia: Mosby/Elsevier, 2007.

![]() 6. Gines, P, Arroyo, V, Quintero, E, et al. Comparison of paracentesis and diuretics in the treatment of cirrhotics with tense ascites-results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 1987; 93(2):234–241.

6. Gines, P, Arroyo, V, Quintero, E, et al. Comparison of paracentesis and diuretics in the treatment of cirrhotics with tense ascites-results of a randomized study. Gastroenterology. 1987; 93(2):234–241.

7. Grewal, P, Martin, P. Pretransplant management of the cirrhotic patient. Clin Liver Dis. 2006; 11(2):431–439.

8. Han, MK, Hyzy, R. Advances in critical care management of hepatic failure and insufficiency. Crit Care Med. 2006; 34(9 Suppl):S225–S231.

9. Hauser SC, ed. Mayo Clinic gastroenterology and hepatology board review, ed 2, Rochester, MN: Mayo Clinic Scientific Press, 2006.

10. Heidelbaugh, JJ, Sherbondy, M, Cirrhosis and chronic liver failure: part II. complications and treatment. Am Fam Physician. 2006; 74(5):767–776.

![]() 11. Hibbard, JS, Analyses comparing the antimicrobial activity of current antiseptic agents. a review. J Infusion Nurs. 2005; 28(3):194–207.

11. Hibbard, JS, Analyses comparing the antimicrobial activity of current antiseptic agents. a review. J Infusion Nurs. 2005; 28(3):194–207.

12. Kaushik, N, Khalid, A, Brody, D. EUS-guided paracentesis for the diagnosis and management of malignant ascites. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006; 64(6):908–913.

13. McGibbon, A, Chen, G, Peltekian, K, et al. An evidence-based manual for abdominal paracentesis. Dig Dis Sci. 2007; 52(12):3307–3315.

![]() 14. Pare, P, Talbot, J, Hoefs, JC, Serum-ascites albumin concentration gradient. a physiologic approach to the differential diagnosis of ascites. Gastroenterology. 1983; 85(2):240–244

14. Pare, P, Talbot, J, Hoefs, JC, Serum-ascites albumin concentration gradient. a physiologic approach to the differential diagnosis of ascites. Gastroenterology. 1983; 85(2):240–244

15. Rodes J, ed.. Textbook of hepatology. from basic science to clinical practice. ed 3. Blackwell Publishing Ltd, Malden, MA, 2007.

16. Rosenberg, SM. Palliation of malignant ascites. Gastroenterol Clin. 2006; 35(1):189–199.

17. Saab, S, Nieto, JM, Lewis, SK, et al. TIPS versus paracentesis for cirrhotic patients with refractory ascites. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 3, 2008.

18. Sanchez, W, Talwalkar, JA. Palliative care for patients with end-stage liver disease ineligible for liver transplantation. Gastroenterol Clin. 2006; 35(1):201–219.

19. Schiff, ER, Sorrell, MF, Maddrey, WC. Schiff’s diseases of the liver, ed 10. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007.

Garcia-Tsao G. Portal hypertension. Curr Opin Gastroenterol. 2006; 22(3):254–262.

Hou, W, Sanyal, AJ, Ascites. diagnosis and management. Med Clin of North Amer. 2009; 93(4):801–817.

Minor, MA, Grace, ND, Pharmacologic therapy of portal hypertension . Clin Liver Dis. 2006; 10(3):563–581.

Thomsen TW, Shaffer RW, White B, et al, eds.. Videos in clinical medicine. paracentesis, N Engl J Med 355( 19). 2007:e21.