Intraabdominal Pressure Monitoring

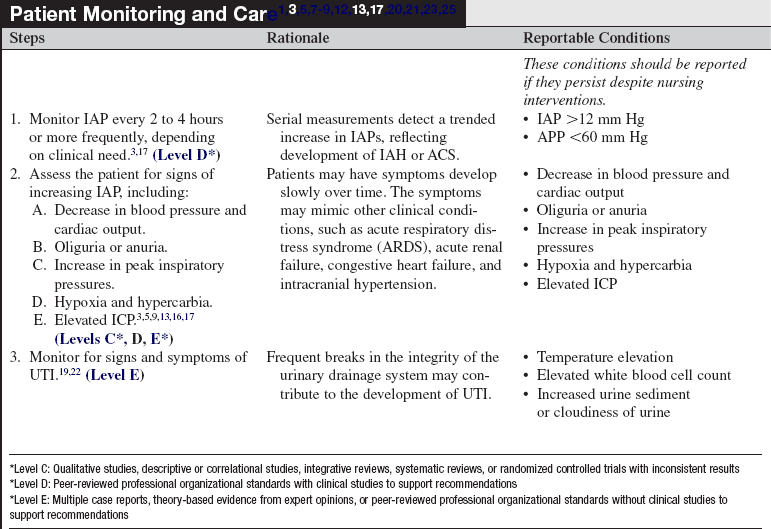

Intraabdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome occur when the abdominal contents expand in excess of the capacity of the abdominal cavity, compromising abdominal organ perfusion and resulting in organ dysfunction or failure and associated mortality.3,5,9,13,14,17,20,23,25

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Understanding of gastrointestinal anatomy and physiology is necessary.

• Knowledge of aseptic technique is essential.

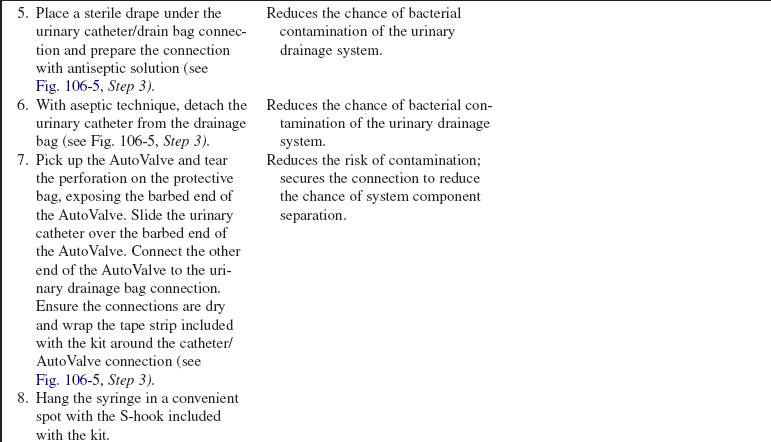

• Intraabdominal hypertension (IAH) and abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS) occur when the abdominal contents expand in excess of the capacity of the abdominal cavity, compromising abdominal organ perfusion and resulting in organ dysfunction or failure and associated mortality.3,5,9,13,14,17,20,23,25

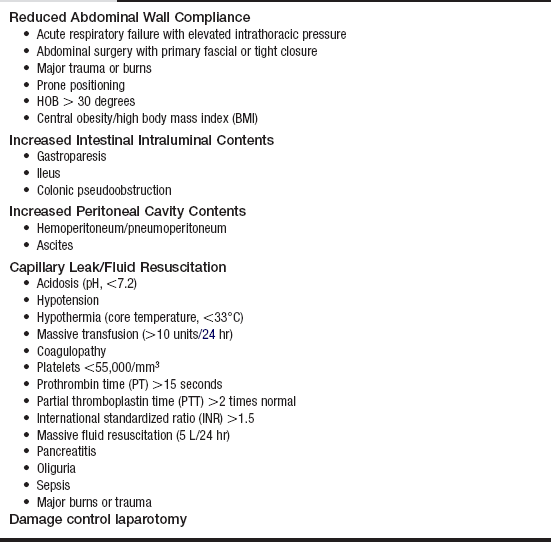

• Four major categories of risk are associated with the development of IAH and ACS (Table 106-1).3,17 They include:

Table 106-1

Patients at Risk for Development of Intraabdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome3,17 (Levels C, D, E*)

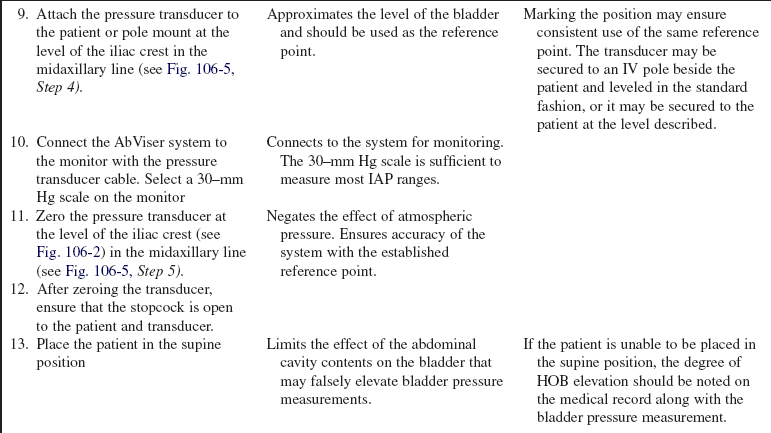

*Level C: Qualitative studies, descriptive or correlational studies, integrative reviews, systematic reviews, or randomized controlled trials with inconsistent results

*Level D: Peer-reviewed, professional organizational standards with clinical studies to support recommendations

*Level E: Multiple case reports, theory-based evidence from expert opinions, or peer-reviewed professional organizational standards without clinical studies to support recommendations

Diminished abdominal wall compliance

Diminished abdominal wall compliance

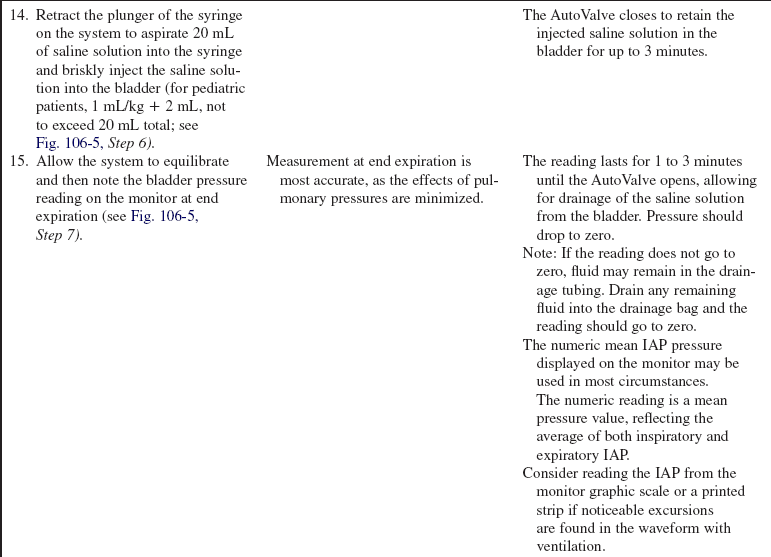

Increased intestinal intraluminal contents

Increased intestinal intraluminal contents

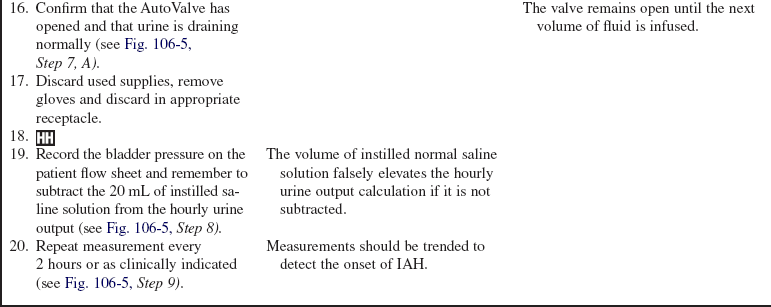

Increased peritoneal cavity contents

Increased peritoneal cavity contents

Capillary leakage into the bowel wall and mesentery/fluid resuscitation

Capillary leakage into the bowel wall and mesentery/fluid resuscitation

• IAH is defined as a sustained or repeated pathologic elevation of intraabdominal pressure (IAP) to more than or equal to 12 mm Hg.3,17

• IAH is graded by severity3,17:

• ACS is defined as IAP more than or equal to 20 mm Hg that is associated with new organ dysfunction or failure.1,3,17,20,21,25 ACS is categorized into three types3,12,17:

Primary ACS: Associated with injury or disease of the abdominopelvic region.

Primary ACS: Associated with injury or disease of the abdominopelvic region.

Secondary ACS: Associated with disease outside the abdominopelvic region (sepsis, burns, fluid resuscitation).

Secondary ACS: Associated with disease outside the abdominopelvic region (sepsis, burns, fluid resuscitation).

Recurrent ACS: ACS that redevelops after previous medical or surgical treatment of primary or secondary ACS.

Recurrent ACS: ACS that redevelops after previous medical or surgical treatment of primary or secondary ACS.

• Both IAH and ACS may compromise perfusion to the visceral organs represented by the parameter: abdominal perfusion pressure (APP).3,6–8,17 APP is derived as:

• APP should be maintained at more than 50 to 60 mm Hg to maintain adequate perfusion to the abdominal organs and reduce the chance of organ dysfunction.3,6,7,17

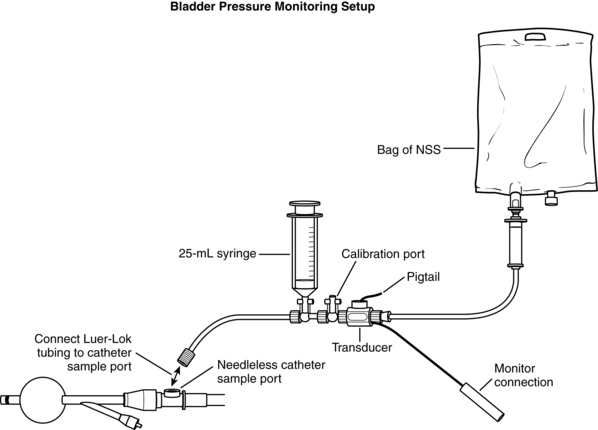

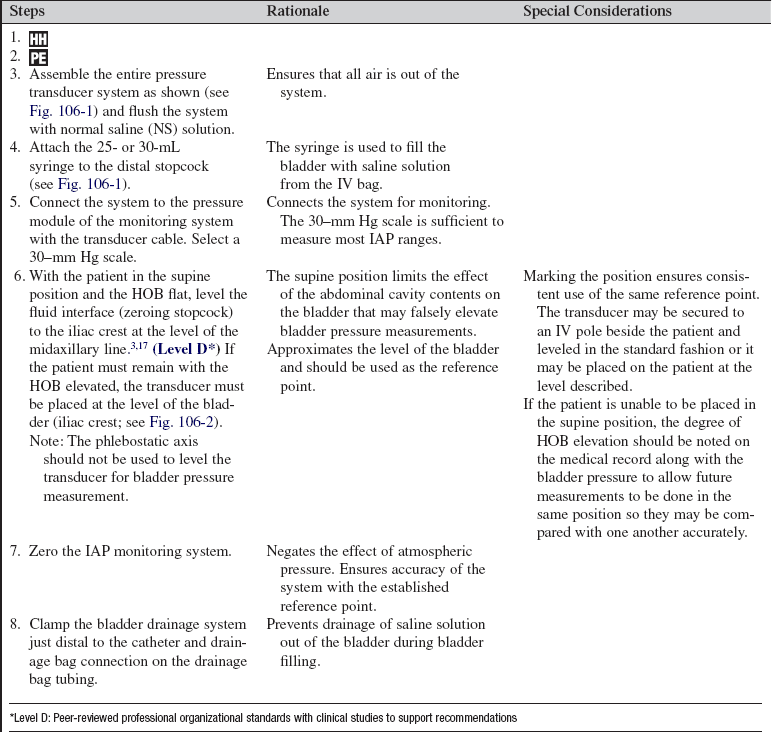

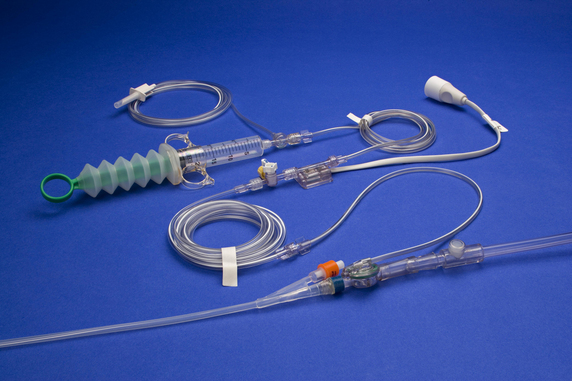

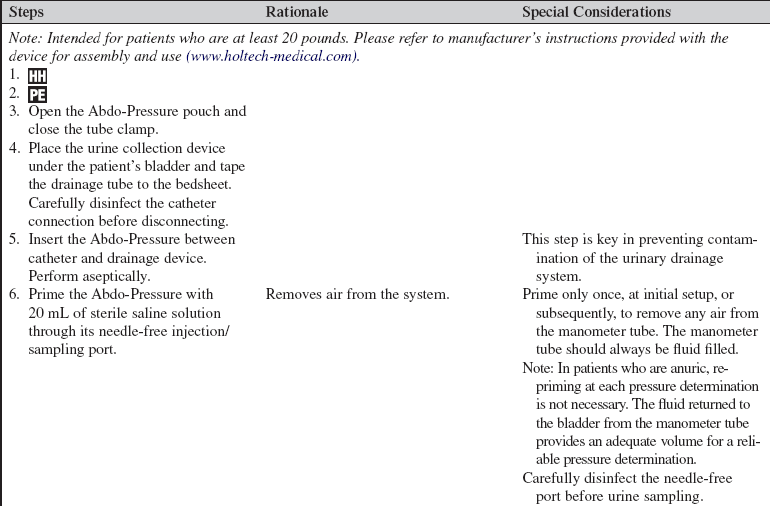

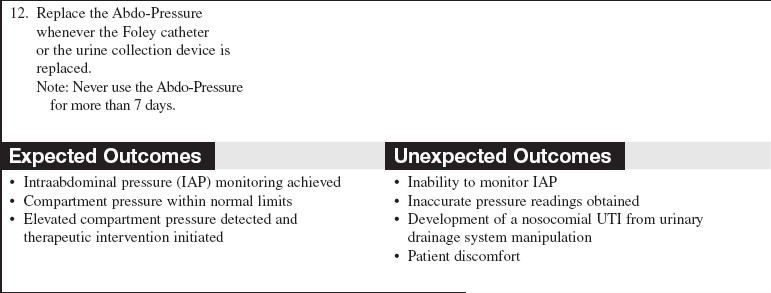

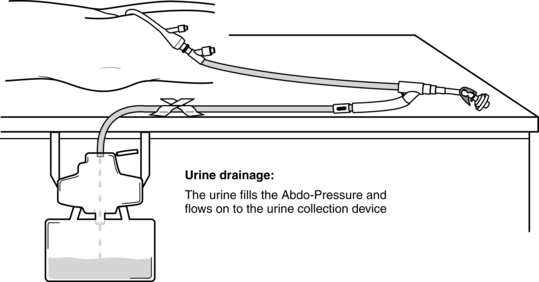

• Measurement of bladder pressure via an indwelling urinary bladder catheter is considered the reference standard for the measurement of IAP and may be performed with equipment readily available in the critical care environment (Fig. 106-1).2,3,8,15,17,22 Commercially prepared kits designed for measurement of IAP are also available and may provide advantages in efficiency, standardization of measurement technique, and data reproducibility. Instructions for specific setup and operation of commercially prepared devices are provided by the manufacturer. Note that regardless of the device used, a standardized procedure for measurement should be used to prevent measurement variability between practitioners.12,15,22

• The bladder acts as a passive reservoir and accurately reflects IAP when intravesicular volumes of 25 mL or less are used. Larger volumes previously suggested (50 to 100 mL) are not necessary and may in fact overdistend the bladder, falsely elevating measured bladder pressure (IAP).3,11,18

• Normal IAP is 0 mm Hg and may even be subatmospheric. In patients who are critically ill, it may rise to 5 to 7 mm Hg.3,17

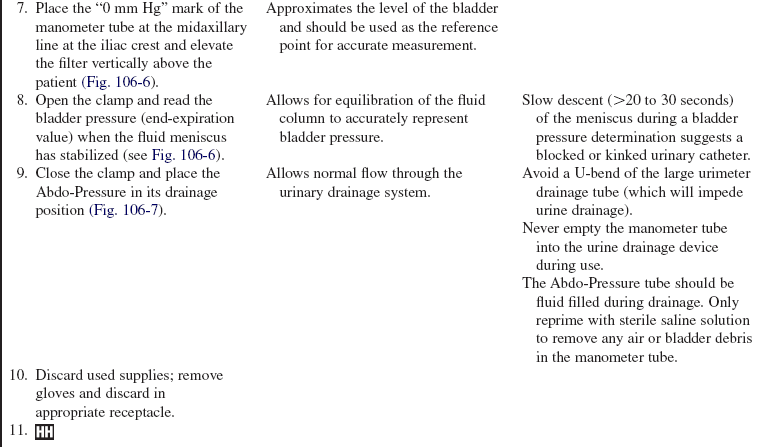

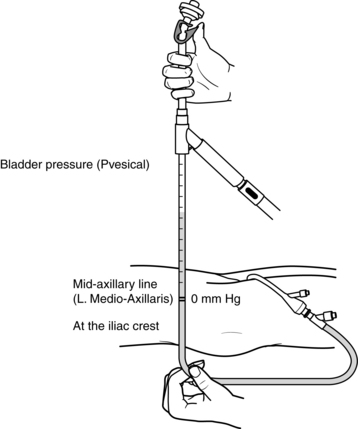

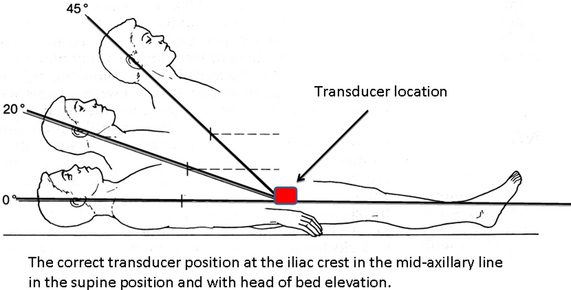

• IAP should be measured with the patient in the supine position. The transducer should be leveled or zeroed at the iliac crest in the midaxillary line (Fig. 106-2).2,3,17,24

Figure 106-2 Correct position of the transducer for bladder pressure measurement. (Illustration by John J. Gallagher.)

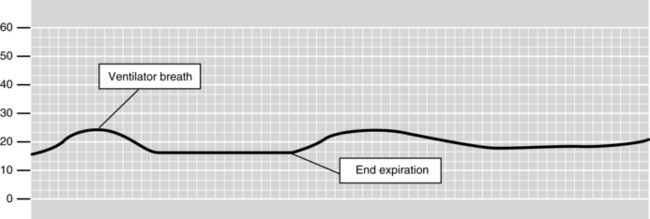

• IAP should be measured at end expiration. Wait an appropriate time (10 to 60 seconds) after saline solution instillation to allow for equilibration of the monitor to a steady state pressure reading.3,17

• IAP should be expressed in millimeters of mercury (mm Hg; 1 mm Hg = 1.36 cm H2O).3,17

• Serial monitoring of bladder pressures is useful in detection of the onset of IAH and the progression to the more severe condition of ACS. Recommendations are that measurements be repeated every 2 to 4 hours in patients with IAP more than or equal to 12 mm Hg so a trend may be established and increases in pressure are detected.3,17

• Bladder pressure measurement may be contraindicated in certain conditions, such as bladder trauma, bladder surgery, and neurogenic bladder. Risks and benefits of measurement should be discussed with the physician before the procedure is performed in these patients.

• In patients who do not have a urinary catheter in place, the risks and benefits of catheter placement for the purpose of bladder pressure measurement should be considered.

EQUIPMENT

• Cardiac monitor and pressure cable for interface with the monitor

• 500- or 1000-mL intravenous (IV) bag of normal saline (NS) solution

• Pressure transducer system, including pressure tubing with flush device, transducer, and two stopcocks

Note: Commercial bladder pressure monitoring system may be substituted for the previous list.

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure of bladder pressure measurement and its purpose to the patient and family.  Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased. Understanding of how the procedure is performed may promote the patient’s ability to cooperate.

Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased. Understanding of how the procedure is performed may promote the patient’s ability to cooperate.

• Inform the patient that fullness may be felt in the bladder when saline solution is injected into the bladder during the procedure.  Rationale: Patient anxiety may be decreased. Patient is prepared for what to expect.

Rationale: Patient anxiety may be decreased. Patient is prepared for what to expect.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Obtain a patient health history to uncover risk factors that may predispose the patient to IAH or ACS. These conditions are outlined in Table 106-1.  Rationale: Patients with these conditions may experience an increase in abdominal cavity fluid collection or tissue edema, placing them at risk for IAH and ACS.3,17

Rationale: Patients with these conditions may experience an increase in abdominal cavity fluid collection or tissue edema, placing them at risk for IAH and ACS.3,17

• Assess the patient for signs of IAH through serial bladder pressure measurement.3,17 Rationale: IAH may be detected early through IAP measurement.

• Assess the patient for signs of progression of IAH to ACS. These findings include decreased cardiac output and blood pressure, oliguria and anuria, increased peak inspiratory pressures (PIPs), hypercarbia and hypoxia, and increased intracranial pressure (ICP);(Table 106-2).1–5,7,9,13,16,17,25,  Rationale: These physical findings indicate pathophysiologic organ system changes associated with the progression of IAH to ACS.3,5–7,9,13,16,17,25

Rationale: These physical findings indicate pathophysiologic organ system changes associated with the progression of IAH to ACS.3,5–7,9,13,16,17,25

Table 106-2

Physiologic Changes Associated with Intraabdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome3,5–7,9,13,16,17,25 (Levels C, D, E*)

| Organ System | Rationale |

| Cardiovascular ↑ CVP, PAP, PCWP, SVR ↓ CO (more pronounced with hypovolemia) ↓ Venous return from lower extremities (risk for DVT) |

Increased abdominal pressure prevents venous return (preload reduction) and impedes arterial outflow (increase in afterload). Transmitted backpressure from the abdominal cavity falsely elevates CVP, PAP, PCWP, PVR, and SVR. CVP and PCWP may be corrected for the influence of increased IAP as follows5: CVP corrected = CVP measured – IAP/2 PCWP corrected = PCWP measured – IAP/2 |

| Renal ↑ Renal blood flow → ↓GFR → ↓urine output |

Increased IAP reduces cardiac output to the kidney, thereby reducing perfusion pressure to the glomerulus. Simultaneously IAP increases the pressure within the renal parenchyma, leading to reduction in filtration. The combination leads to a marked reduction in GFR and urine production. |

| Pulmonary ↑ Intrathoracic pressures ↑ Peak inspiratory pressures ↓ Tidal volume → hypercarbia + ↓PaO2 ↓ Compliance |

Increased IAP causes an increase in intrathoracic pressure and limits diaphragm excursion, resulting in hypoventilation and hypoxia. |

| Neurologic ↑ICP ↓CPP |

Increased IAP impedes venous outflow from the brain, increasing cerebral venous congestion. |

| Gastrointestinal/hepatic effect ↓Celiac and portal blood flow ↓Lactate clearance ↓Mucosal blood flow → ↓ pHi |

Increased IAP reduces perfusion to the abdominal organs. Capillary blood flow becomes obstructed as the IAP rises. When the IAP achieves and surpasses the venous capillary pressure, capillary blood flow is reduced or ceases. Transfer of oxygen/nutrients stops leading to anaerobic metabolism. |

*Level C: Qualitative studies, descriptive or correlational studies, integrative reviews, systematic reviews, or randomized controlled trials with inconsistent results

*Level D: Peer-reviewed, professional organizational standards with clinical studies to support recommendations

*Level E: Multiple case reports, theory-based evidence from expert opinions, or peer-reviewed professional organizational standards without clinical studies to support recommendations

Patient Preparation

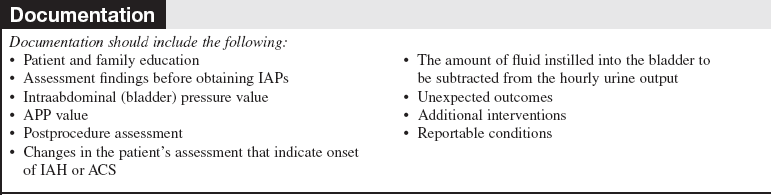

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teachings. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Ensure the presence of a conventional (single-lumen) urinary catheter connected to a drainage system.  Rationale: A urinary catheter with a drainage system is required to obtain bladder pressure measurements. Multilumen irrigation urinary catheters also may be used but are not required.

Rationale: A urinary catheter with a drainage system is required to obtain bladder pressure measurements. Multilumen irrigation urinary catheters also may be used but are not required.

• Place the patient in the supine flat position (if this can be tolerated) in preparation for bladder pressure measurement. The transducer should be placed at the iliac crest at the level of the midaxillary line (see Fig. 106-2).3,17  Rationale: The supine flat position reduces the effect of downward pressure from the abdominal organs on the bladder, reducing the chance that IAP is falsely elevated. Patients who cannot tolerate the supine position (head injury, respiratory compromise) may have measurements taken with the head of the bed (HOB) elevated.3,17 If the patient must remain with the HOB elevated, the transducer must be placed at the level of the bladder (iliac crest; see Fig. 106-2).

Rationale: The supine flat position reduces the effect of downward pressure from the abdominal organs on the bladder, reducing the chance that IAP is falsely elevated. Patients who cannot tolerate the supine position (head injury, respiratory compromise) may have measurements taken with the head of the bed (HOB) elevated.3,17 If the patient must remain with the HOB elevated, the transducer must be placed at the level of the bladder (iliac crest; see Fig. 106-2).

• Documentation should reflect the degree of reverse Trendelenburg’s or HOB elevation when measurements are not obtained in the supine position.2,3,17,24  Rationale: IAP results can be evaluated in light of the patient’s position at the time of measurement. Note that the phlebostatic axis should not be used to level the transducer for bladder pressure measurement.

Rationale: IAP results can be evaluated in light of the patient’s position at the time of measurement. Note that the phlebostatic axis should not be used to level the transducer for bladder pressure measurement.

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Figure 106-3 IAP waveform. The IAP read at end expiration is 16 mm Hg in this patient on mechanical ventilation.

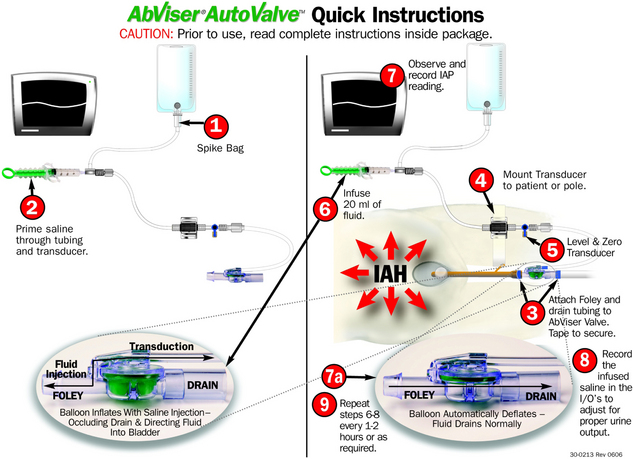

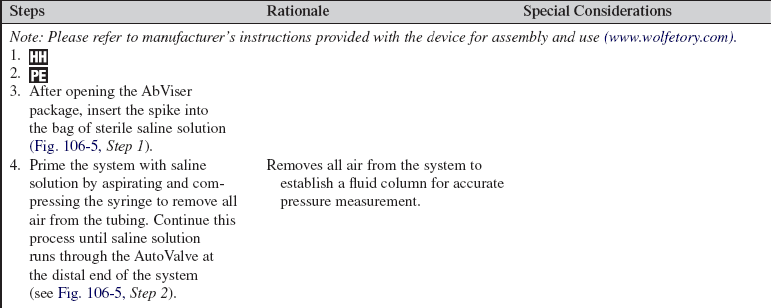

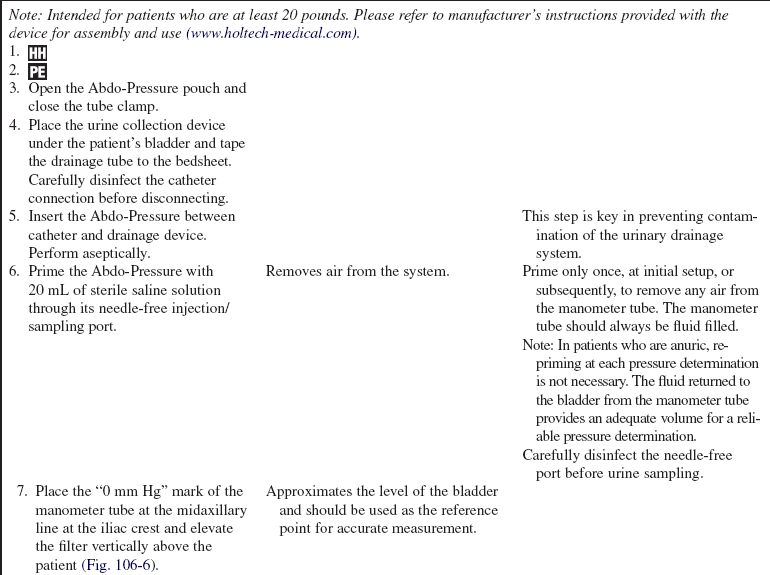

Procedure for Intraabdominal Pressure Monitoring with the Wolfe Tory Medical AbViser (Wolfe Tory Medical, Salt Lake City, Utah) Bladder Pressure Monitoring System with AutoValve (Fig. 106-4)

References

![]() 1. Balogh, Z, et al. Secondary abdominal compartment syndrome is an elusive early complication of traumatic shock resuscitation. Am J Surg. 2002; 184:538–543.

1. Balogh, Z, et al. Secondary abdominal compartment syndrome is an elusive early complication of traumatic shock resuscitation. Am J Surg. 2002; 184:538–543.

2. Cheatham, ML, et al, The impact on body position on intra-abdominal pressure measurement. a multicenter analysis. Crit Care Med 2009; 37:2187–2190.

3. Cheatham, ML, et al, Results from the International Conference of Experts on Intra-abdominal Hypertension and Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. IIrecommendations. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33(6):951–962.

4. Cheatham, ML, Safcsak, K. Is the evolving management of IAH/ACS improving survival. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2007; 62(Suppl 1):268. [Abstract 061].

5. Cheatham, ML, Malbrain, MLNG. Cardiovascular implications of abdominal compartment syndrome. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2007; 62(Suppl 1):98–112.

6. Cheatham, ML, Malbrain, MLNG. Abdominal perfusion pressure. In: Cheatham ML, Malbrain MLNG, Sugrue M, eds. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Georgetown, TX: Landes Biomedical; 2006:69–81.

![]() 7. Cheatham, ML, et al, Abdominal perfusion pressure . a superior parameter in the assessment of intraabdominal hypertension. J Trauma 2000; 56:237–242.

7. Cheatham, ML, et al, Abdominal perfusion pressure . a superior parameter in the assessment of intraabdominal hypertension. J Trauma 2000; 56:237–242.

![]() 8. Cheatham, ML, Safcak, K, Intraabdominal pressure. a revised method for measurement. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 186:594–595.

8. Cheatham, ML, Safcak, K, Intraabdominal pressure. a revised method for measurement. J Am Coll Surg 1998; 186:594–595.

![]() 9. Cullen, D, et al. Cardiovascular, pulmonary, and renal effects of massively increased intraabdominal pressure in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1989; 17:118–122.

9. Cullen, D, et al. Cardiovascular, pulmonary, and renal effects of massively increased intraabdominal pressure in critically ill patients. Crit Care Med. 1989; 17:118–122.

![]() 10. De Potter TJ, Dits, H, Malbrain, MLNG. Intra- and interobserver variability during in vitro validation of two novel methods for intra-abdominal pressure monitoring. Intensive Care Med. 2005; 31(5):747–751.

10. De Potter TJ, Dits, H, Malbrain, MLNG. Intra- and interobserver variability during in vitro validation of two novel methods for intra-abdominal pressure monitoring. Intensive Care Med. 2005; 31(5):747–751.

11. De Waele JJ, et al, Saline volume in transvesical intra-abdominal pressure measurement. enough is enough. Intensive Care Med. 2006; 32(3):455–459.

![]() 12. Gracias, VH, et al. Abdominal compartment syndrome in the open abdomen. Arch Surg. 2002; 137:1298–1300.

12. Gracias, VH, et al. Abdominal compartment syndrome in the open abdomen. Arch Surg. 2002; 137:1298–1300.

![]() 13. Kashtan, J, et al. Hemodynamic effects of increased intraabdominal pressure. J Surg Res. 1981; 30:249–255.

13. Kashtan, J, et al. Hemodynamic effects of increased intraabdominal pressure. J Surg Res. 1981; 30:249–255.

14. Kimball, EJ, et al. Clinical awareness of intra-abdominal hypertension and abdominal compartment syndrome in 2007. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2007; 62(Suppl 1):66–73.

15. Kimball, EJ, et al. Reproducibility of bladder pressure measurements in critically ill patients. Intensive Care Med. 2007; 33(7):98–1195.

![]() 16. Kron, I, Harman, K, Nolan, SP. The measurement of intraabdominal pressure as a criterion for abdominal re-exploration. Ann Surg. 1984; 199:28–30.

16. Kron, I, Harman, K, Nolan, SP. The measurement of intraabdominal pressure as a criterion for abdominal re-exploration. Ann Surg. 1984; 199:28–30.

17. Malbrain, MLNG, Delaet, I, Cheatham, ML, Consensus conference definitions and recommendations on intraabdominal hypertension (IAH) and the abdominal compartment syndrome (ACS). the long road to the final publicationshow did we get there. Acta Clinica Belgica. 2007; 62(Suppl 1):44–59.

18. Malbrain, MLNG, Deeren, D, Effect of bladder volume on measuring intravesical pressure. a prospective cohort study. Crit Care Forum. 2006; 10(4):1–6.

19. Malbrain, MLNG, Jones, F, et al. Intra-abdominal pressure measurement techniques. In: Ivatury RR, Cheatham ML, Malbrain M, eds. Abdominal compartment syndrome. Georgetown, TX: Landis Bioscience, 2006.

![]() 20. Malbrain, MLNG, et al, Incidence and prognosis of intraabdominal hypertension in a mixed population of critically ill patients. a multiple-center epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33(2):315–322.

20. Malbrain, MLNG, et al, Incidence and prognosis of intraabdominal hypertension in a mixed population of critically ill patients. a multiple-center epidemiological study. Crit Care Med. 2005; 33(2):315–322.

![]() 21. Malbrain, MLNG, et al, Prevalence of intra-abdominal hypertension in critically ill patients. a multicentre epidemiological study. Intensive Care Med. 2004; 30(5):822–829.

21. Malbrain, MLNG, et al, Prevalence of intra-abdominal hypertension in critically ill patients. a multicentre epidemiological study. Intensive Care Med. 2004; 30(5):822–829.

![]() 22. Malbrain, MLNG, Different techniques to measure intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). time for a critical re-appraisal. Intensive Care Med. 2004; 30(3):357–371.

22. Malbrain, MLNG, Different techniques to measure intra-abdominal pressure (IAP). time for a critical re-appraisal. Intensive Care Med. 2004; 30(3):357–371.

![]() 23. Malbrain, MLNG. Abdominal perfusion pressure as a prognostic marker in intraabdominal hypertension. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of intensive care and emergency medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2002:792–814.

23. Malbrain, MLNG. Abdominal perfusion pressure as a prognostic marker in intraabdominal hypertension. In: Vincent JL, ed. Yearbook of intensive care and emergency medicine. Berlin, Heidelberg, New York: Springer; 2002:792–814.

24. Vasquez, DG, Berg-Copas GM, Wetta-Hall R. Influence of semi-recumbent position on intra-abdominal pressure as measured by bladder pressure. J Surg Res. 2007; 139(2):280–285.

25. Wolfe, TR, Kimball, EJ, McLean, B. The interrelationship of severe sepsis, sepsis resuscitation and the abdominal compartment syndrome. Int J Intensive Care. 2008; 87–91. [Spring].

Ivatury, RR, Cheatham, ML, Malbrain, M, et al, Abdominal compartment syndrome. Landis Bioscience, Georgetown, TX, 2006.

World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. World Society of the Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. Accessed June 10, 2009 www.wsacs.org. [(website)].

Abdominal Compartment Syndrome, Abdominal Compartment Syndrome. org. Sponsored by Wolfe Tory Medical (website). www.abdominalcompartmentsyndrome.org [Accessed June 10, 2009].

Intra-abdominal Pressure Monitoring. Holtech Medical. (website) www.holtech-medical.com. [Accessed June 10, 2009].

Wolfe Tory Medical. Wolfe Tory Medical. (website) www.wolfetory.com. [Accessed June 10, 2009].