Peripheral Nerve Blocks: Assisting with Insertion and Pain Management

Peripheral nerve blocks are administered as single local anesthetic injections or continuously through a catheter placed into a precise anatomic area to provide site-specific (e.g., femoral, brachial plexus, axillary, intrapleural, extrapleural, paravertebral, tibial, sciatic, and lumbar plexus) prolonged anesthesia or analgesia for postoperative and trauma pain management.7,33,34 The use of peripheral nerve blocks requires skilled and knowledgeable health care providers.7,33,34 Catheter placement and the continuing treatment of the patient should be under the direct supervision of an anesthesiologist, nurse anesthetist, or the acute pain service.22,33

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• State boards of nursing may have detailed guidelines involving peripheral nerve blockade. Each institution that provides this therapy also has policies and guidelines pertaining to peripheral nerve blockade. It is important that the nurse is aware of state guidelines and institution policies.

• The nurse must have an understanding of the principles of aseptic technique.7,10,16,21,35 Peripheral nerve blocks are used as part of a preemptive and multimodal analgesic technique to provide safe and effective postoperative pain management with minimal side effects.8,10,12,15,19

• An understanding of the physiology of pain is essential. Pain is defined as an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or is described in terms of such damage.1,7,30

• Tissue trauma caused by surgery or injury initiates a series of biochemical events that release numerous endogenous chemicals that promote pain transmission, damage to body tissues, alterations in blood clotting, impaired immune function, and autonomic nervous system stimulation.1 The pathophysiologic effects of pain, such as delayed gastric emptying, development of ileus, and reductions in respiratory tidal volumes, may all predispose patients in pain to postoperative secondary infection.1,7

• No matter how successful or how deftly conducted, surgical operations produce tissue trauma and release potent mediators of inflammation and pain.23 Pain is just one response to trauma or surgery. Substances released from injured tissue evoke stress hormone responses in the patient. Such responses promote breakdown of body tissue; increase metabolic rate, blood clotting, and water retention; impair immune function; and trigger a fight-or-flight alarm reaction with autonomic features (e.g., rapid pulse) and negative emotions.1,7

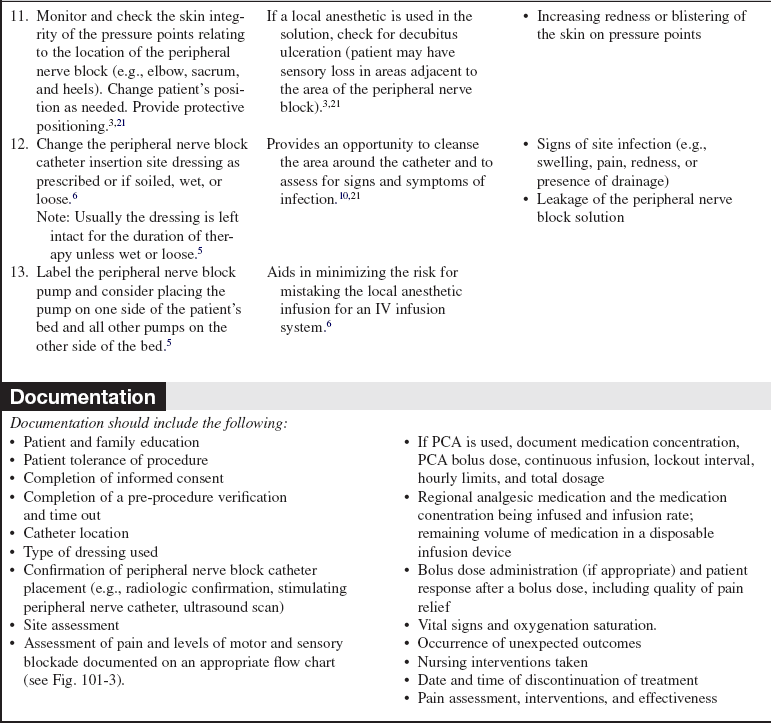

• The patient in pain may attempt to “splint” the injured site, resulting in shallow breathing and cough suppression, followed by retained pulmonary secretions and pneumonia.3,9,11,16 Unrelieved pain also may delay the return of normal gastric and bowel function in the patient after surgery.3,5

• The basis for the efficacy and utility of peripheral nerve blockade in patients with acute pain is the interruption of nociceptive input at its source and through nociceptive transmissions in the peripheral nerve.7,21 In addition to blocking nociceptors in the incision, a continuous infusion may attenuate pain-mediating substances, such as histamine, bradykinin, and prostaglandins.23

• Peripheral nerve blocks with local anesthetics can be used to treat acute pain regionally in a number of ways. These vary from wound infiltration to continuous peripheral nerve blockade with the use of catheters that provide many hours or days of optimal analgesia after surgery or trauma.12,13,16

• Peripheral nerve blocks provide well-documented advantages in the postoperative period, including blunting of the surgical/trauma stress response, excellent analgesia, earlier extubation, less sedation, decreased incidence of pulmonary complications, reduction in blood loss, earlier return of bowel function, decreased deep venous thrombosis, earlier ambulation, earlier discharge from high-acuity units, and possibly shorter hospital stays.7,21,29

• Peripheral nerve blocks in the outpatient setting have facilitated early patient ambulation and discharge by decreasing side effects, such as drowsiness, nausea, and vomiting.3,9,11,15 In addition, unlike general anesthesia, peripheral nerve blocks do not alter the level of consciousness. By preserving the patient’s level of consciousness, the patient’s protective airway reflexes (e.g., cough and gag) are maintained and the need for airway manipulation and intubation is negated. Furthermore, with the use of peripheral nerve blockade, the complications of general anesthesia are avoided.3 Continuous peripheral nerve blockade improves postoperative analgesia, patient satisfaction, and rehabilitation compared with intravenous opioids for upper and lower extremity procedures.9,11,15,24,28

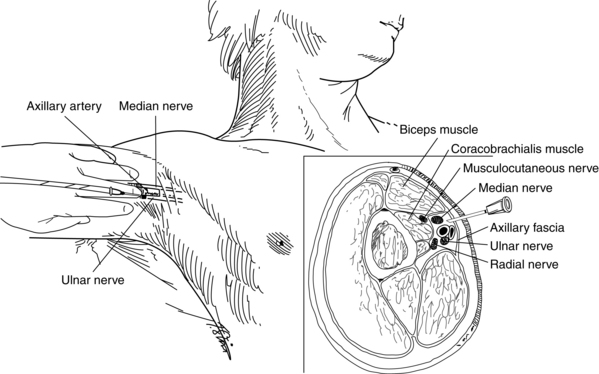

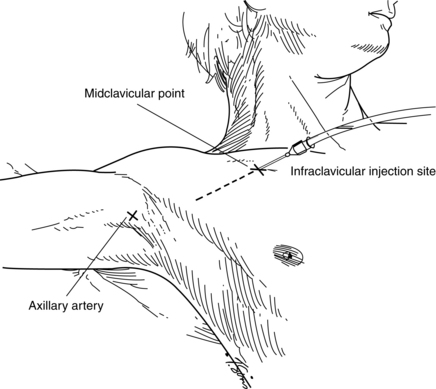

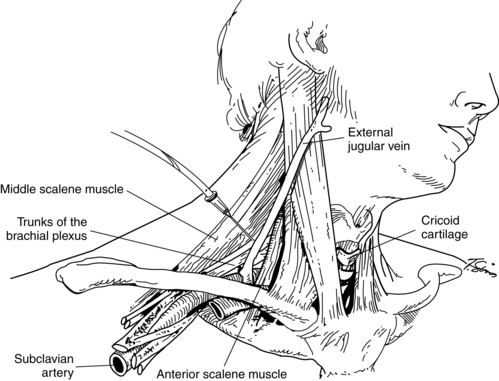

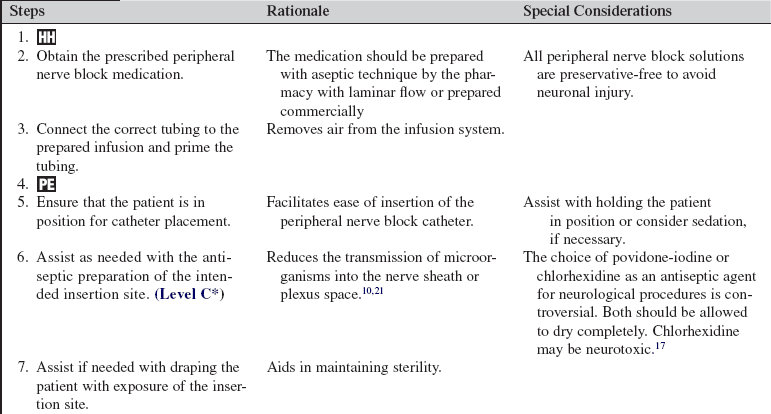

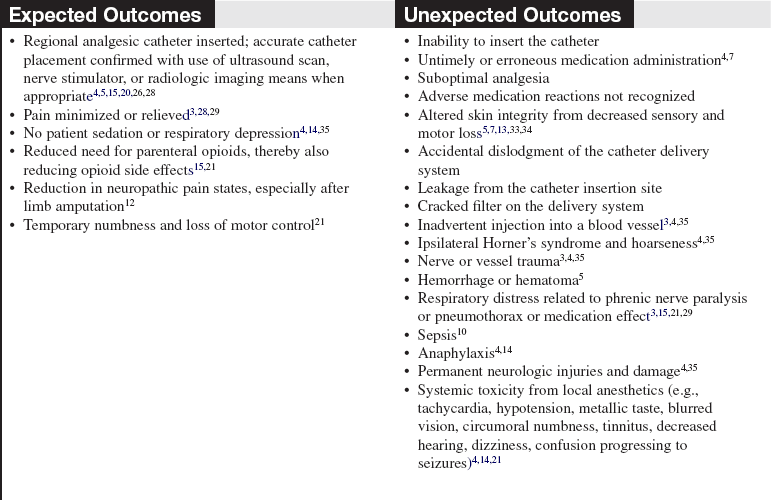

• The anatomic position of the specific catheter is clearly defined and documented after insertion (e.g., femoral, axillary [Figs. 103-1 and 103-2], brachial plexus [Fig. 103-3], intrapleural, extrapleural, paravertebral, tibial, sciatic, and lumbar plexus).4,29 Radiologic confirmation5 of the catheter position may be necessary to avoid suboptimal outcomes (e.g., pneumothorax). Catheters may be placed by the surgeon, anesthesiologist, or certified nurse anesthetist (CRNA) under direct vision, via ultrasound scan–guided techniques or with the use of a peripheral nerve stimulator, either adjacent to or directly into the nerve sheath (e.g., sciatic or tibial nerve during surgery for lower limb amputation).13,16,19–21,26,28 Catheters may also be placed after surgery (e.g., intercostals, intrapleural, axillary, brachial plexus, femoral, and paravertebral; Table 103-1).

Table 103-1

Single-Shot and Continuous Peripheral Nerve Blocks in the Critically Ill

| Block | Indications | Practical Problems |

| Interscalene | Shoulder/arm pain (e.g., shoulder dislocation/fractures, humeral fracture) | Horner’s syndrome may obscure neurologic assessment Block of ipsilateral phrenic nerve Close proximity to tracheostomy and jugular vein line sites |

| Cervical paravertebral (continuous catheter only) | Shoulder/elbow/wrist pain (e.g., shoulder fractures, humeral fracture, elbow fractures, wrist fractures) | Horner’s syndrome may obscure neurologic assessment Block of ipsilateral phrenic nerve Patient positioning |

| Infraclavicular | Arm/hand pain (e.g., elbow fractures, wrist fractures) | Pneumothorax risk Steep angle for catheter placement Interference with subclavian lines |

| Axillary | Arm/hand pain (e.g., elbow fractures, wrist fractures) | Arm positioning Catheter maintenance |

| Paravertebral | Unilateral chest or abdominal pain restricted to few dermatomes (e.g., rib fractures) | Patient positioning Stimulation success sometimes hard to visualize |

| Combination of femoral and sciatic block | Unilateral leg pain (e.g., femoral neck fracture [femoral], tibial and ankle fractures [sciatic])* | Patient positioning Interference of femoral nerve catheters with femoral lines |

*Caution: Compartment syndrome.

(Modified from Schulz-Stubner S: The critically ill patient and regional anesthesia, Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 19:538-544, 2006.)

• A three-in-one peripheral nerve block can be used for analgesia after proximal lower limb orthopedic surgery. A three-in-one peripheral nerve block provides analgesia to block three nerves, including the lateral femoral cutaneous, femoral, and obturator nerves.24 This block is as effective as epidural analgesia, with fewer side effects than epidural analgesia (e.g., urinary retention, nausea, and risk for epidural hemorrhage in patients with anticoagulation).5,6,13,18,24 Some forms of plexus analgesia (e.g., brachial plexus analgesia) in the postoperative setting may serve two purposes: pain relief and sympathetic blockade, the latter of which increases blood flow and may improve outcomes in some cases (i.e., digit reimplantation).4,13,21,31

• Analgesia via a catheter may be administered as a continuous infusion with the use of a volumetric pump system, a patient-controlled regional infusion system, or a disposable pump device (e.g., elastomeric). Elastomeric pumps are one type of disposable infusion pump designed to provide a constant rate of infusion from a filled reservoir. The infusion rates are not adjustable (Fig. 103-4.)19,27,31 Medication administered is usually a local anesthetic (e.g., bupivacaine, ropivacaine). Other agents have been used on an adjunctive basis as a bolus, including opioids, clonidine, epinephrine,13,14 and neostigmine.15

Figure 103-4 An elastomeric infusion pump. Parts include: 1, filling port; 2, elastomeric balloon (drug-containing reservoir); and 3, outer protective shell. (Originally published in Skryabina E, Dunn TS: Disposable infusion pumps, Am J Health Syst Pharm 63:1260-1268, 2006.) © 2006, American Society of Health-System Pharmacists, Inc. All rights reserved. Reprinted with permission (R1002).

• The pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics of local anesthetics and other agents used, including side effects and duration of action, should be clearly understood. Local anesthetic medications used for peripheral nerve blocks provide surgical analgesia (i.e., loss of pain sensation) and anesthesia (i.e., loss of all sensation). The duration of action for each anesthetic medication depends on several factors, including the volume injected, concentration of the medication, site of injection, and absorption. The addition of a vasoconstrictor, such as epinephrine, constricts blood vessels and reduces vascular uptake, which further prolongs the duration of action of the local anesthetic.13,14 Epinephrine should not be used in peripheral nerve blocks in areas with end arteries, such as ear lobes, the nose, digits, and the penis.35 Vasoconstrictor medications may cause spasm of blood vessels, resulting in necrosis.7 Knowledge of signs and symptoms of profound motor and sensory blockade, or overmedication, is essential.4,7,8,14

• Sensory and motor blockade may be acceptable or desirable, depending on the physician’s goals and preference. The loss of sensation at the site is often the primary goal of blocks, and although motor loss is often acceptable, it is not desirable.3

• According to the American Pain Society, the most common reason for unrelieved pain in hospitals is failure of health care providers to routinely and adequately assess pain and pain relief.2 Many patients silently tolerate unrelieved pain if not specifically asked about it.1,2,14 Patient self report is considered the best indicator of pain.2,30 Behavioral observations are unreliable indicators of pain levels.1,2

• Contraindications to peripheral nerve blockade include a history of coagulopathy, preexisting neuropathies, anatomic or pathologic deviations at the injection site, and systemic disease or infection.4–6,8,18,20,35

EQUIPMENT

• One peripheral nerve catheter kit

• Infusion set for continuous plexus anesthesia with or without an adaptor for a nerve stimulator

• Topical skin antiseptic, as prescribed (e.g., 2% chlorhexidine-based preparation or povidone-iodine)

• Sterile gloves, fluid shield face masks, sterile gowns

• 20 mL normal saline solution

• 5 to 10 mL local anesthetic as prescribed (1% lidocaine) for local infiltration

• Local anesthetic as prescribed (to establish the block)

• Occlusive dressing supplies to cover the catheter entry site

• Gauze and tape to secure the catheter to the patient’s body

• Labels stating “Local anesthetic only” and “Not for intravenous injection”

• Pump for administration of analgesia (e.g., volumetric pump, dedicated for peripheral nerve block infusion with rate and volume limited, and preferably a different color from the epidural and intravenous infusion pumps; patient-controlled analgesic pump or a portable infusion device such as an elastomeric [PCA]) pump

• Specific observation chart for patient monitoring of the peripheral nerve block infusion

• Prescribed analgesics and local anesthetics

• Equipment for monitoring blood pressure, heart rate, and pulse oximetry

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the reason and purpose of the catheter. If available, supply easy-to-read patient information.  Rationale: The patient and the family know what to expect; anxiety may be reduced.

Rationale: The patient and the family know what to expect; anxiety may be reduced.

• Explain to the patient and family that the procedure can be uncomfortable but that a local anesthetic will be used to facilitate comfort.  Rationale: Explanation elicits patient’s cooperation and comfort and facilitates insertion; anxiety and fear may be decreased.

Rationale: Explanation elicits patient’s cooperation and comfort and facilitates insertion; anxiety and fear may be decreased.

• During therapy, instruct the patient to report side effects or changes in pain management (e.g., suboptimal analgesia, profound numbness of extremities [beyond the goal of therapy], lightheadedness, metallic taste, circumoral numbness, dizziness, blurred vision, tinnitus, loss of hearing and seizures).4,7,14,21  Rationale: Reporting of pain aids patient’s comfort level and identifies side effects.

Rationale: Reporting of pain aids patient’s comfort level and identifies side effects.

• Teach the patient to protect the affected extremity from injury and trauma (e.g., burns).3,4,21  Rationale: Patient safety is increased, and the limb is protected from injury and trauma.

Rationale: Patient safety is increased, and the limb is protected from injury and trauma.

• If a PCA pump is used, educate the patient and family on its use. Reinforce the education throughout PCA therapy. (see Procedure 102)  Rationale: Prepares the patient and family for effectively using the PCA system.

Rationale: Prepares the patient and family for effectively using the PCA system.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Observe the patient for local infection or generalized sepsis.  Rationale: Decreases the risk for infection at the site of catheter insertion. Septicemia and bacteremia are contraindications for peripheral nerve block catheter placement or continuation of therapy.8,10

Rationale: Decreases the risk for infection at the site of catheter insertion. Septicemia and bacteremia are contraindications for peripheral nerve block catheter placement or continuation of therapy.8,10

• Assess the patient’s concurrent anticoagulant and fibrinolytic therapy.5,6,35  Rationale: Heparin (unfractionated and low–molecular-weight heparin) and heparinoids and fibrinolytic agents administered concurrently increase the risk for vessel trauma (e.g., hematoma). Care must be taken with insertion and removal of the peripheral nerve block catheter when patients are on anticoagulant and fibrinolytic therapy.7 Special institutional guidelines must be observed.3–6,16,23 Insertion and removal of the peripheral nerve catheter should be directed by the physician.4–6,18

Rationale: Heparin (unfractionated and low–molecular-weight heparin) and heparinoids and fibrinolytic agents administered concurrently increase the risk for vessel trauma (e.g., hematoma). Care must be taken with insertion and removal of the peripheral nerve block catheter when patients are on anticoagulant and fibrinolytic therapy.7 Special institutional guidelines must be observed.3–6,16,23 Insertion and removal of the peripheral nerve catheter should be directed by the physician.4–6,18

• Obtain the patient’s vital signs.  Rationale: Provides baseline data.

Rationale: Provides baseline data.

• Assess the patient’s pain.  Rationale: Provides baseline data.

Rationale: Provides baseline data.

• Review the patient’s medication allergies.  Rationale: Review of medication allergies before administration of a new medication decreases allergic reactions.

Rationale: Review of medication allergies before administration of a new medication decreases allergic reactions.

Patient Preparation

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that the patient and family understand the planned procedure. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Ensure that informed consent has been obtained.  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Wash the specific anatomic area of the patient’s body with soap and water and open the gown to expose the site for injection while maintaining the patient’s privacy and dignity.  Rationale: This action cleanses the skin and allows easy access to the specific anatomic area of the patient’s body.

Rationale: This action cleanses the skin and allows easy access to the specific anatomic area of the patient’s body.

• Consider nothing by mouth (NPO), especially if sedation or general anesthesia is to be used.  Rationale: The risk for vomiting and aspiration is decreased.

Rationale: The risk for vomiting and aspiration is decreased.

• Establish intravenous (IV) access or ensure the patency of IV lines.  Rationale: The need to treat hypotension or respiratory depression may occur.

Rationale: The need to treat hypotension or respiratory depression may occur.

• Position the patient as appropriate, according to which anatomic area of the body is to be blocked.  Rationale: Prepares the patient for the procedure.

Rationale: Prepares the patient for the procedure.

• Reassure the patient.  Rationale: Anxiety and fears may be reduced.

Rationale: Anxiety and fears may be reduced.

References

![]() 1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel, Clinical practice guidelines. acute pain managementoperative or medical -procedures and trauma,AHCPR pub. 92-0032. Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, 1992.

1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research, Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel, Clinical practice guidelines. acute pain managementoperative or medical -procedures and trauma,AHCPR pub. 92-0032. Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services, Rockville, MD, 1992.

2. American Pain Society. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute and cancer pain, ed 6. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2008.

![]() 3. Barnes, S, Russell, S. Interscalene blocks in the -ambulatory setting. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004; 19:352–354.

3. Barnes, S, Russell, S. Interscalene blocks in the -ambulatory setting. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004; 19:352–354.

![]() 4. Bergman, BD, Hebl, JR, Kent, J, et al. Neurologic complications of 405 consecutive continuous axillary catheters. Anesth Analg. 2003; 96:247–252.

4. Bergman, BD, Hebl, JR, Kent, J, et al. Neurologic complications of 405 consecutive continuous axillary catheters. Anesth Analg. 2003; 96:247–252.

5. Bickler, P, Brandes, J, Lee, M, et al. Bleeding complications from femoral and sciatic nerve catheters in patients receiving low molecular weight heparin. Anesth Analg. 2006; 103:1036–1037.

6. Buckenmaier, CC, Bleckner, LL. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks and anticoagulation. Br J Anaesth. 2008; 101:139–140.

7. Burkard, J, Vacchiano, CA. Regional anesthesia. In: Nagelhout JJ, Plaus K, eds. Nurse anesthesia. ed 4. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2009:977–1030.

![]() 8. Capdevila, X, Pirat, P, Bringuler, S, et al, Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery. a multicenter prospective analysis of the quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416 patients. Anesthesiology 2005; 103:1035–1045.

8. Capdevila, X, Pirat, P, Bringuler, S, et al, Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in hospital wards after orthopedic surgery. a multicenter prospective analysis of the quality of postoperative analgesia and complications in 1,416 patients. Anesthesiology 2005; 103:1035–1045.

9. Capdevila, X, Dadure, C, Bringuier, S, et al, Effect of patient-controlled perineural analgesia on rehabilitation and pain after ambulatory orthopedic surgery. a multicenter randomized trial. Anesthesiology 2006; 105:566–573.

10. Capdevila, X, Jaber, S, Pesonen, P, et al. Acute neck cellulitis and mediastinitis complicating a continuous interscalene block. Anesth Analg. 2008; 107:1419–1421.

11. Capdevila, X, Ponrouch, M, Choquet, O. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks in clinical practice. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2008; 21:619–623.

![]() 12. Chelly, JE, Ben-David B, Williams, BA, et al, Anesthesia and postoperative analgesia. outcomes following orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2003; 26(8 Suppl):S865–S871.

12. Chelly, JE, Ben-David B, Williams, BA, et al, Anesthesia and postoperative analgesia. outcomes following orthopedic surgery. Orthopedics. 2003; 26(8 Suppl):S865–S871.

![]() 13. Couture, DJ, Cuniff, HM, Mave, JP, et al. The addition of clonidine to bupivacaine in combined femoral-sciatic nerve block for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. AANA J. 2004; 72:273–278.

13. Couture, DJ, Cuniff, HM, Mave, JP, et al. The addition of clonidine to bupivacaine in combined femoral-sciatic nerve block for anterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. AANA J. 2004; 72:273–278.

![]() 14. Cox, B, Durieux, ME, Marcus, MA. Toxicity of local anesthetics. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003; 17:111–136.

14. Cox, B, Durieux, ME, Marcus, MA. Toxicity of local anesthetics. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2003; 17:111–136.

![]() 15. Grossi, PA, Allegri, MB, Continuous peripheral nerve blocks. state of the art. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2005; 18:522–526.

15. Grossi, PA, Allegri, MB, Continuous peripheral nerve blocks. state of the art. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2005; 18:522–526.

16. Hadzic, A, Sala-Blanch X, Xu, D. Ultrasound guidance may reduce but not eliminate complications of peripheral nerve blocks. Anesthesiology. 2008; 108:557–558.

17. Hebl, JR. The importance and implications of aseptic techniques during regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006; 31:311–323.

![]() 18. Horlocker, TT, Wedel, DJ, Benzon, H, et al, Regional anesthesia in the anticoagulated patient. defining the risks. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28:172–197.

18. Horlocker, TT, Wedel, DJ, Benzon, H, et al, Regional anesthesia in the anticoagulated patient. defining the risks. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28:172–197.

![]() 19. Kamming, D, Chung, F, Williams, D, et al. Pain management in ambulatory surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004; 19:174–182.

19. Kamming, D, Chung, F, Williams, D, et al. Pain management in ambulatory surgery. J Perianesth Nurs. 2004; 19:174–182.

![]() 20. Marhofer, P, Greher, M, Kapral, S. Ultrasound guidance in regional anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005; 94:7–17.

20. Marhofer, P, Greher, M, Kapral, S. Ultrasound guidance in regional anaesthesia. Br J Anaesth. 2005; 94:7–17.

21. McCamant, KL, Peripheral nerve blocks. understanding the nurse’s role. J Perianesth Nurs 2006; 21:16–24.

![]() 22. McDonnell, A, Nicholl, J, Read, SM, Acute pain teams and the management of postoperative pain. a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 2003; 41:261–273.

22. McDonnell, A, Nicholl, J, Read, SM, Acute pain teams and the management of postoperative pain. a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Adv Nurs 2003; 41:261–273.

23. Mertin, S, Sawatzky, JA, Diehl-Jones WL, et al, Roadblock to recovery. the surgical stress response. Dynamics 2007; 18:14–20.

![]() 24. Morau, D, Lopez, S, Biboulet, P, et al, Comparison of continuous 3-in-1 and fascia iliaca compartment blocks for postoperative analgesia. feasibility, catheter migration, distribution of sensory block, and analgesic efficacy. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28:309–314.

24. Morau, D, Lopez, S, Biboulet, P, et al, Comparison of continuous 3-in-1 and fascia iliaca compartment blocks for postoperative analgesia. feasibility, catheter migration, distribution of sensory block, and analgesic efficacy. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28:309–314.

25. Pasero, C, Eksterowicz, N, Primeau, M, et al, Registered nurse management and monitoring of analgesia by catheter techniques. position statement. Pain Manag Nurs 2007; 8:48–54.

![]() 26. Pham-Dang C, Kick, O, Collet, T, et al. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks with stimulating catheters. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003; 28:83–88.

26. Pham-Dang C, Kick, O, Collet, T, et al. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks with stimulating catheters. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003; 28:83–88.

27. Remerand, F, Vuitton, AS, Palud, M, et al, Elastomeric pump reliability in postoperative regional anesthesia. a survey of 430 consecutive devices. Anesth Analg 2008; 107:2079–2084.

![]() 28. Salinas, FV, Location, location, location. continuous peripheral nerve blocks and stimulating catheters. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28:79–82.

28. Salinas, FV, Location, location, location. continuous peripheral nerve blocks and stimulating catheters. Reg Anesth Pain Med 2003; 28:79–82.

29. Schulz-Stubner S. The critically ill patient and regional anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006; 19:538–544.

30. Sessler, CN, Grap, MJ, Ramsay, MA, Evaluating and monitoring analgesia and sedation in the intensive care unit available at. Crit Care. 2008; 12(Suppl 3):S2. http://ccforum.com/content/12/S3/S3 [accessed October 15, 2009].

![]() 31. Shinaman, RC, Mackey, S. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005; 9:24–29.

31. Shinaman, RC, Mackey, S. Continuous peripheral nerve blocks. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2005; 9:24–29.

32. Skryabina, E, Dunn, TS. Disposable infusion pumps. Am J Health Syst Pharm. 2006; 63:1260–1268.

33. Tsui, BCH, Rosenquist, RW. Peripheral nerve blockade. In: Barash PG, Cullen BF, Stoelting RK, et al, eds. Clinical anesthesia. ed 6. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:955–1002.

34. Wedel, DJ, Horlocker, TT. Nerve blocks. In: Miller RD, Eriksson LI, Fleisher LA, et al, eds. Miller’s anesthesia. ed 7. London: Churchill Livingstone; 2009:1639–1674.

35. Wiegel, M, Gottschaldt, U, Hennebach, R, et al. Complications and adverse effects associated with continuous peripheral nerve blocks in orthopedic patients. Anesth Analg. 2007; 104:1578–1582.

Mulroy, MF, Bernards, CM, McDonald, SB, et al. A practical approach to regional anesthesia, ed 4. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2008.

Richman, JM, Liu, SS, Courpas, G, et al. Does continuous peripheral nerve block provide superior pain control to opioids? A meta-analysis. Anesth Analg. 2006; 102:248–257.

Turjanica, MA. Postoperative continuous peripheral nerve blockade in the lower extremity total joint arthroplasty population. Medsurg Nurs. 2007; 16:151–154.