Epidural Catheters: Assisting with Insertion and Pain Management

Epidural catheters are used to provide regional anesthesia and analgesia by delivering medications directly into the epidural space surrounding the spinal cord. Medications injected into the epidural space are capable of providing dose-related site-specific anesthesia and analgesia. Epidural catheters can be used effectively for short-term (e.g., acute, obstetric, postoperative, trauma) or long-term (e.g., chronic, advanced cancer) pain management.7,20

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• State boards of nursing may have detailed guidelines involving epidural analgesia. Each institution that provides this therapy also has policies and guidelines pertaining to epidural therapy. It is important that the nurse is aware of state guidelines and institution policies.

• The nurse must have an understanding of the principles of aseptic technique.13,22,23,27

• The epidural catheter placement and the continuing pain management of the patient should be under the supervision of an anesthesiologist, nurse anesthetist, or acute pain service to ensure positive patient outcomes.2,12

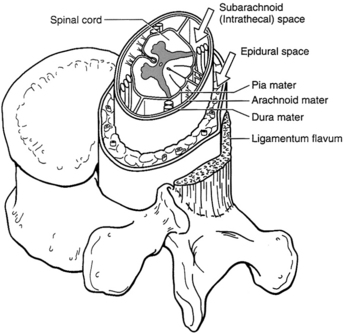

• The spinal cord and brain are covered by three membranes, collectively called the meninges. The outer layer is the dura mater. The middle layer is the arachnoid mater, which lies just below the dura mater and, with the dura, forms the dural sac. The innermost layer is the pia mater, which adheres to the surface of the spinal cord and the brain. The cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) circulates in the subarachnoid space, which is also called the intrathecal space.29

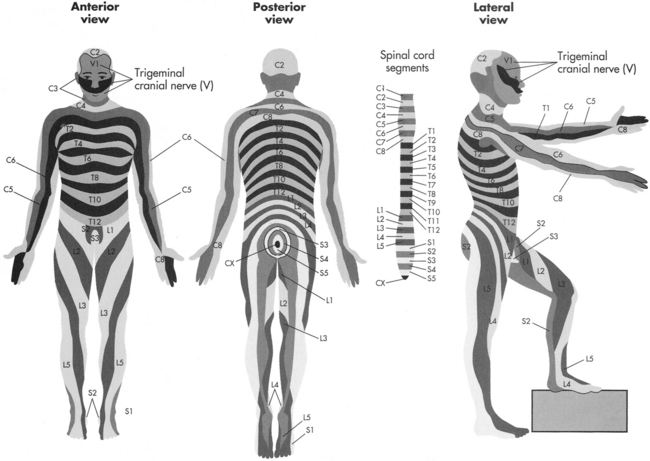

• The epidural space lies between the dura mater and the bone and ligaments of the spinal canal (Fig. 101-1).

• The epidural space (potential space) contains fat, large blood vessels, connective tissue, and spinal nerve roots.

• Analgesia via an epidural catheter may be given with a continuous, intermittent, or patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) pump system.17,29

• A variety of medication options are available, including local anesthetics, opiates, mixtures of local anesthetics and opiates, α2-adrenergic agonists (e.g., clonidine), and other agents.13,17 All medications should be preservative-free for epidural administration.4,7,12,13

• The pharmacology of agents given for epidural analgesia, including side effects and duration of action, must be understood.22

• Knowledge of the signs and symptoms of profound motor and sensory blockade or overmedication is essential. Intravenous (IV) access, IV volume loading, and immediate availability of an opioid antagonist and vasopressors are necessary.4,12,22

• According to the American Pain Society (APS), the most common reason for unrelieved pain in hospitals is the failure of staff to routinely and adequately assess pain and pain relief. Many patients silently tolerate unrelieved pain if not specifically asked about it.1

• The Agency for Health Care Policy and Research (AHCPR) urges healthcare professionals to accept the patient’s self-report as “the single most reliable indicator of the existence and intensity” of pain. Behavioral observations are unreliable indicators of pain levels.1

• Pain is an unpleasant sensory and emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage.1,7

• No matter how successfully or deftly conducted, surgical operations produce tissue trauma. Trauma caused by surgery or injury initiates a series of biochemical events that release numerous endogenous chemicals, which potentiate mediators of inflammation and pain.16

• Pain is just one response to the trauma of surgery. In addition to pain, the substances released from injured tissue evoke stress hormone responses in the patient. Such responses promote pain transmission, breakdown of body tissues, increased metabolic rate, blood clotting, water retention, and impaired immune function and trigger a fight-or-flight alarm reaction with autonomic nervous system stimulation features (e.g., rapid pulse).1,4,13

• The psychologic effects of pain include depression, anxiety, and other negative emotions.1,6,7

• The patient may attempt to “splint” the injured site, resulting in shallow breathing and cough suppression followed by retained pulmonary secretions and pneumonia.12,13 Unrelieved pain also may delay the return of normal gastric emptying and cause development of an ileus, impairment of bowel function, and reductions in respiratory tidal volumes, all of which may predispose patients in pain to infection after surgery.7,8,19,30

• Epidural analgesia provides a number of well-documented advantages in the postoperative period, including attenuation of the surgical/trauma stress response, excellent analgesia, earlier extubation, less sedation, decreased incidence of pulmonary complications, earlier return of bowel function, decreased deep venous thrombosis, earlier ambulation, earlier discharge from high-acuity units,12,14,20,30 and possibly shorter hospital stays.20,32

EQUIPMENT

• One epidural catheter kit or the following supplies:

One 25-gauge, ⅝-inch (0.5 × 16 mm) injection needle

One 25-gauge, ⅝-inch (0.5 × 16 mm) injection needle

One 23-gauge, 1¼-inch (0.6 × 30 mm) injection needle

One 23-gauge, 1¼-inch (0.6 × 30 mm) injection needle

One 18-gauge, 1½-inch (1.2 × 40 mm) injection needle

One 18-gauge, 1½-inch (1.2 × 40 mm) injection needle

One Luer-Lok loss-of-resistance syringe

One Luer-Lok loss-of-resistance syringe

• One introducer stabilizing catheter guide

• One screw-cap Luer-Lok catheter

• One screw-cap Luer-Lok catheter connector

• One 0.2 × m epidural flat filter

• Topical skin antiseptic, as prescribed (e.g., 2% chlorhexidine non–alcohol-based preparation)

• Sterile gloves, face masks with eye shields, sterile gowns

• 20 mL normal saline solution

• 5 to 10 mL local anesthetic as prescribed (e.g., 1% lidocaine; local infiltration)

• 5 mL local anesthetic as prescribed to establish the block

• Test dose (e.g., 3 mL 2% lidocaine with epinephrine, 1:200,000)

• Gauze or transparent dressing to cover the epidural catheter entry site

• Tape to secure the epidural catheter to the patient’s back and over the patient’s shoulder

• Labels stating “Epidural only” and “Not for intravenous injection”

• Pump for administering analgesia (e.g., volumetric pump, dedicated for epidural use with rate and volume limited, which has the ability to be locked to prevent tampering and preferably is a color-coded [e.g., yellow] or patient-controlled epidural analgesia pump)

• Dedicated epidural portless administration set

• Specific observation chart for patient monitoring of the epidural infusion

• Prescribed medication analgesics and local anesthetic medications

• Equipment for monitoring blood pressure, heart rate, and pulse oximetry

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the reason and purpose of the epidural catheter. If available, supply easy-to-read written information.  Rationale: This information prepares the patient and family for what to expect.

Rationale: This information prepares the patient and family for what to expect.

• Explain to the patient and family that the insertion procedure can be uncomfortable but that a local anesthetic will be used to facilitate comfort.  Rationale: Explanation promotes patient cooperation and comfort, facilitates insertion, and decreases anxiety and fear.

Rationale: Explanation promotes patient cooperation and comfort, facilitates insertion, and decreases anxiety and fear.

• During insertion and therapy, instruct the patient to immediately report adverse side effects, such as ringing in the ears, a metallic taste in the mouth, or numbness or tingling around the mouth, because these are signs indicative of local anesthetic toxicity.12,29,32  Rationale: Immediate reporting identifies side effects and impending serious complications.

Rationale: Immediate reporting identifies side effects and impending serious complications.

• During insertion and therapy, instruct the patient to report changes in pain management (e.g., suboptimal analgesia), numbness of extremities, loss of motor function of lower extremities, acute onset of back pain, loss of bladder and bowel function, itching, and nausea and vomiting.4,12,13,17.  Rationale: Education regarding adverse side effects allows for more rapid assessment and management of potential complications.

Rationale: Education regarding adverse side effects allows for more rapid assessment and management of potential complications.

• If the epidural infusion is patient-controlled, ensure that patient and family understand that only the patient is to activate the medication release.  Rationale: The patient should remain alert enough to administer his or her own dose. A safeguard to oversedation is that a patient cannot administer additional medication doses if sedated.

Rationale: The patient should remain alert enough to administer his or her own dose. A safeguard to oversedation is that a patient cannot administer additional medication doses if sedated.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Assess the patient for local infection and generalized sepsis.  Rationale: Assessment decreases the risk for epidural infection (e.g., epidural abscess).30 Septicemia and bacteremia are contraindications for epidural catheter placement.4,8,23,27

Rationale: Assessment decreases the risk for epidural infection (e.g., epidural abscess).30 Septicemia and bacteremia are contraindications for epidural catheter placement.4,8,23,27

• Assess the patient’s concurrent anticoagulation therapy.  Rationale: Heparin (unfractionated) or heparinoids (e.g. low-molecular-weight heparin) administered concurrently during epidural catheter placement increases the risk for epidural hematoma and paralysis. Care must be taken with insertion and removal of the epidural catheter when patients have received anticoagulation therapy. Anticoagulant and fibrinolytic medications may increase the risk for epidural hematoma and spinal cord damage and paralysis. If used, anticoagulants must be withheld before insertion and removal of the epidural catheter.21,25,26 Removal of the epidural catheter should be directed by the physician. According to Kleinman and Mikhail,12 aspirin or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications (NSAIDs) by themselves do not pose an increased risk for epidural hematoma, assuming the patient’s coagulation profile is within normal limits. Therefore, aspirin or NSAIDs may be administered while the epidural catheter is in place.12 However, epidural hematomas have been associated with the concurrent administration of the NSAIDs, ketorolac, and anticoagulants.5,21 Assessment of sensory and motor function must be regularly performed during epidural analgesia for all patients.

Rationale: Heparin (unfractionated) or heparinoids (e.g. low-molecular-weight heparin) administered concurrently during epidural catheter placement increases the risk for epidural hematoma and paralysis. Care must be taken with insertion and removal of the epidural catheter when patients have received anticoagulation therapy. Anticoagulant and fibrinolytic medications may increase the risk for epidural hematoma and spinal cord damage and paralysis. If used, anticoagulants must be withheld before insertion and removal of the epidural catheter.21,25,26 Removal of the epidural catheter should be directed by the physician. According to Kleinman and Mikhail,12 aspirin or nonsteroidal antiinflammatory medications (NSAIDs) by themselves do not pose an increased risk for epidural hematoma, assuming the patient’s coagulation profile is within normal limits. Therefore, aspirin or NSAIDs may be administered while the epidural catheter is in place.12 However, epidural hematomas have been associated with the concurrent administration of the NSAIDs, ketorolac, and anticoagulants.5,21 Assessment of sensory and motor function must be regularly performed during epidural analgesia for all patients.

• Obtain the patient’s vital signs.  Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

• Assess the patient’s pain.  Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

Rationale: Baseline data are provided.

• Review the patient’s medication allergies.  Rationale: This information may decrease the possibility of an allergic reaction.

Rationale: This information may decrease the possibility of an allergic reaction.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that informed consent has been obtained.  Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

Rationale: Informed consent protects the rights of the patient and makes a competent decision possible for the patient.

• Perform a pre-procedure verification and time out, if non-emergent.  Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

Rationale: Ensures patient safety.

• Wash the patient’s back with soap and water and open the gown in the back.  Rationale: This action cleanses the skin and allows easy access to the patient’s back.

Rationale: This action cleanses the skin and allows easy access to the patient’s back.

• Consider nothing by mouth (NPO), especially if sedation or general anesthesia is to be used.  Rationale: NPO status decreases the risk for vomiting and aspiration.

Rationale: NPO status decreases the risk for vomiting and aspiration.

• Establish IV access, or ensure the patency of IV lines, and administer IV fluids as prescribed before epidual catheter insertion.  Rationale: IV access ensures that medications can be given quickly if needed. The administration of IV fluids may decrease hypotension that may occur during epidural infusions.4,12

Rationale: IV access ensures that medications can be given quickly if needed. The administration of IV fluids may decrease hypotension that may occur during epidural infusions.4,12

• Reassure the patient.  Rationale: Anxiety and fears may be reduced.

Rationale: Anxiety and fears may be reduced.

References

![]() 1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guidelines: acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma, AHCPR pub 92-0032. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1992.

1. Agency for Health Care Policy and Research Acute Pain Management Guideline Panel. Clinical practice guidelines: acute pain management: operative or medical procedures and trauma, AHCPR pub 92-0032. Rockville, MD: Public Health Service, US Department of Health and Human Services; 1992.

![]() 2. Ashburn, MA, Caplan, RA, Carr, DB, et al, Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology 2004; 100:1573–1581.

2. Ashburn, MA, Caplan, RA, Carr, DB, et al, Practice guidelines for acute pain management in the perioperative setting. an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Anesthesiology 2004; 100:1573–1581.

3. Bedforth, NM, Aitkenhead, AR, Hardman, JG. Haematoma and abscesses after epidural analgesia an updated report by the American Society of Anesthesiologists Task Force on Acute Pain Management. Br J Anesth. 2008; 101:291–293.

![]() 4. Burkard, J, Olson, RL, Vacchiano, CA. Regional anesthesia. In: Nagelhout JJ, Zaglaniczny KL, eds. Nurse anesthesia. ed 3. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2004:977–1030.

4. Burkard, J, Olson, RL, Vacchiano, CA. Regional anesthesia. In: Nagelhout JJ, Zaglaniczny KL, eds. Nurse anesthesia. ed 3. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2004:977–1030.

![]() 5. Chan, L, Bailin, MT, Spinal epidural hematoma following central neuraxial blockade and subcutaneous enoxaparin. a case report. J Clin Anesth 2004; 16:382–385.

5. Chan, L, Bailin, MT, Spinal epidural hematoma following central neuraxial blockade and subcutaneous enoxaparin. a case report. J Clin Anesth 2004; 16:382–385.

6. Dunwoody, CJ, Krenzischek, DA, Pasero, C, et al. Assessment, physiological monitoring, and consequences of inadequately treated acute pain. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008; 23(Suppl 1):S15–S27.

![]() 7. Faut-Callahan M, Hand, WR. Pain management. In: Nagelhout JJ, Zaglaniczny KL, eds. Nurse anesthesia. ed 3. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2004:1157–1182.

7. Faut-Callahan M, Hand, WR. Pain management. In: Nagelhout JJ, Zaglaniczny KL, eds. Nurse anesthesia. ed 3. St Louis: Elsevier Saunders; 2004:1157–1182.

8. Gendall, KA, Kennedy, RR, Watson, AJ, et al. The effect of epidural analgesia on postoperative outcome after gastrointestinal surgery. Colorectal Dis. 2007; 9:584–598.

![]() 9. Gordon, DB, Dahl, JH, Miaskowski, C, et al. American Pain Society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:1574–1580.

9. Gordon, DB, Dahl, JH, Miaskowski, C, et al. American Pain Society recommendations for improving the quality of acute and cancer pain management. Arch Intern Med. 2005; 165:1574–1580.

![]() 10. Hebl, JR. The importance and implications of aseptic techniques during regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003; 31:311–323.

10. Hebl, JR. The importance and implications of aseptic techniques during regional anesthesia. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2003; 31:311–323.

11. Horlocker, TT, Burton, AW, Connis, RT, et al. Practice guidelines for the prevention, detection, and management of respiratory depression associated with neuroaxial opioid administration. Anesthesiology. 2009; 110:218–230.

12. Kleinman, W, Mikhail, MS, Spinal, epidural and caudal blocksMorgan GE, Mikhail MS, Murray MJ, eds.. Clinical anesthesiology. ed 4. McGraw- Hill, New York, 2006:289–323.

![]() 13. Mahlmeister, L, Nursing responsibilities in preventing, preparing for, and managing epidural emergencies. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2003; 17:19–32.

13. Mahlmeister, L, Nursing responsibilities in preventing, preparing for, and managing epidural emergencies. J Perinat Neonatal Nurs 2003; 17:19–32.

14. Marret, E, Remy, C, Bonnet, F, Postoperative pain forum group. meta-analysis of epidural local analgesia versus parenteral opioid analgesia after colorectal surgery. Br J Surg 2007; 94:665–673.

15. Meikle, J, Bird, S, Nightingale, JJ, et al, Detection and management of epidural haematomas related to anesthesia in the UK. a national survey of current practice. Br J Anaesth 2008; 101:400–404.

16. Mertin, S, Sawatzky, JA, Diehl-Jones WL, et al, Roadblock to recovery. the surgical stress response. Dynamics 2007; 18:14–20.

17. Miaskowski, C, Bair, M, Chou, R, et al. Principles of analgesic use in the treatment of acute and cancer pain, ed 6. Glenview, IL: American Pain Society; 2008.

18. Milstone, AM, Passaretti, CL, Perl, TM, Chlorhexidine . expanding the armamentarium for infection control and prevention. Clin Infect Dis 2008; 46:274–281.

19. Morgan, GE, Mikhail, MS, Murray, MJ. Pain management. In: Morgan GE, Mikhail MS, Murray MJ, eds. Clinical anesthesiology. ed 4. New York: McGraw-Hill Company; 2006:359–412.

![]() 20. Pasero, C. Improving postoperative outcomes with epidural analgesia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005; 20:51–55.

20. Pasero, C. Improving postoperative outcomes with epidural analgesia. J Perianesth Nurs. 2005; 20:51–55.

21. Pasero, C, McCaffery, M. Orthopaedic postoperative pain management. J Perianesth Nurs. 2007; 22:160–172.

22. Pasero, C, Eksterowicz, N, Primeau, M, et al. The registered nurse’s role in the management of analgesia by catheter techniques. J Perianesth Nurs. 2008; 23:53–56.

23. Ranasinghe, JS, Lee, AJ, Birnbach, DJ, Infection associated with central venous or epidural catheters. how to reduce it. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol 2008; 21:386–390.

24. Reynolds, F. Neurologic infections after neuroaxial anesthesia. Anesthesiol Clin. 2008; 26:23–52.

![]() 25. Rowlingson, JC, Hanson, PB. Neuraxial anesthesia and low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis in major orthopedic surgery in the wake of the latest American Society of Regional Anesthesia guidelines. Anesth Analg. 2005; 100:1482–1488.

25. Rowlingson, JC, Hanson, PB. Neuraxial anesthesia and low-molecular-weight heparin prophylaxis in major orthopedic surgery in the wake of the latest American Society of Regional Anesthesia guidelines. Anesth Analg. 2005; 100:1482–1488.

26. Ruppen, W, Derry, S, McQuay, HJ, et al, Incidence of epidural haematoma and neurological injury in cardiovascular patients with epidural analgesia/anaesthesia. systematic review and meta analysis. BMC Anesthesiol. 2006; 6(10). www.biomedcentral.com/1471-2253-6-10 [accessed September 1, 2009, from].

27. Ruppen, W, Derry, S, McQuay, HJ, et al, Infection rates associated with epidural indwelling catheters for seven days or longer. systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Palliat Care. 2007; 3(6). www.biomedcentral.com/1472-684X/6/3 [accessed September 1, 2009, from].

28. Schulz-Stubner S. The critically ill patient and regional anesthesia. Curr Opin Anaesthesiol. 2006; 19:538–544.

29. St. Marie B. Pain management. In: Weinstein SM, ed. Plumer’s principles and practice of intravenous therapy. ed 8. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2007:576–607.

30. Tenenbein, PK, Debrouwere, R, Maguire, D, et al. Thoracic epidural analgesia improves pulmonary function in patients undergoing cardiac surgery. Can J Anaesth. 2008; 55:344–350.

31. Wedel, DJ, Horlocker, TT. Regional anesthesia in the febrile or infected patient. Reg Anesth Pain Med. 2006; 31:324–333.

32. Weetman, C, Allison, W. Use of epidural analgesia in post-operative pain management. Nurs Stand. 2006; 20:54–64.