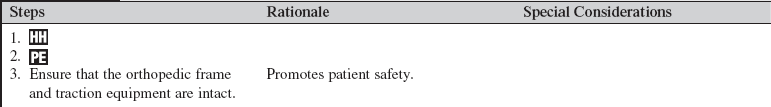

Cervical Traction Maintenance

PREREQUISITE NURSING KNOWLEDGE

• Knowledge of neuroanatomy and physiology is necessary.

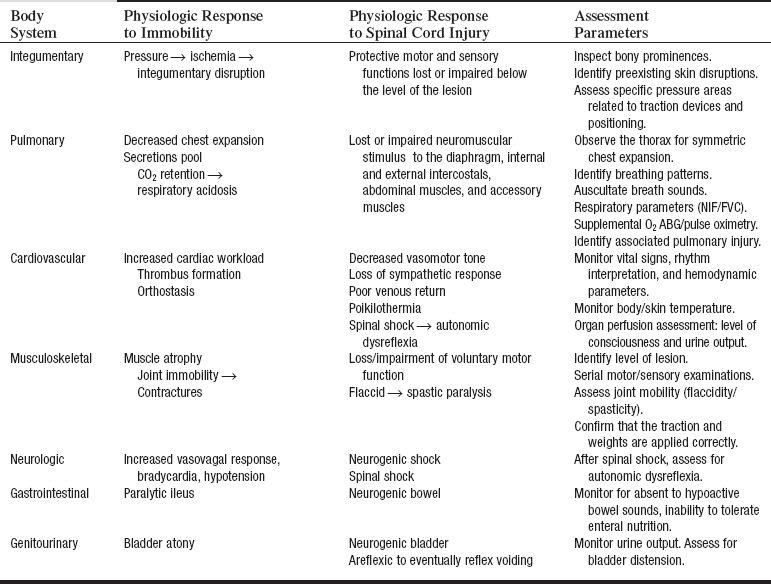

• The nurse needs to be knowledgeable about the anatomy and physiology of the spinal column, the special anatomy of the cervical vertebrae, the spinal cord, the cervical spinal nerves, and their areas of innervation. In addition, the nurse must understand the pathophysiology and manifestations of spinal cord trauma, including spinal shock, ascending edema, and related impairment of respiratory function, decreased vasomotor tone, and autonomic nervous system dysfunction.1,2,10

• The nurse needs to be knowledgeable about the signs and symptoms of new spinal cord injury or extension of injury and the needed interventions.

• After the cervical tongs are inserted, traction is applied by adding weights to a rope and pulley or cable and bracket alignment device attached to the tongs (see Fig. 97-1). Additional weight may be added gradually, followed with radiographic imaging. The physician uses serial radiographs of the cervical spine to assist in determining the optimal amount of traction (measured in pounds) needed to reduce a fracture and provide optimal alignment. Excessive traction may cause stretching of and damage to the spinal cord; the addition of weight to the traction is managed by the physician.3,9

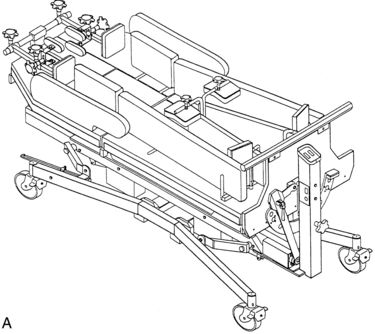

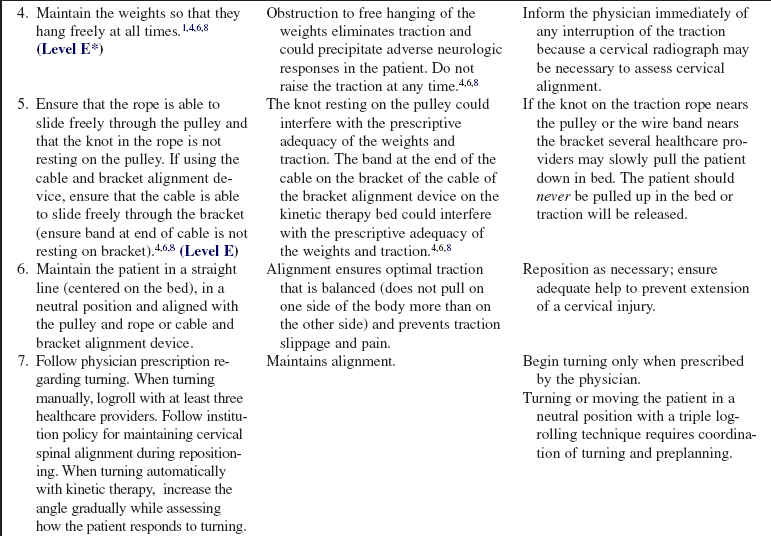

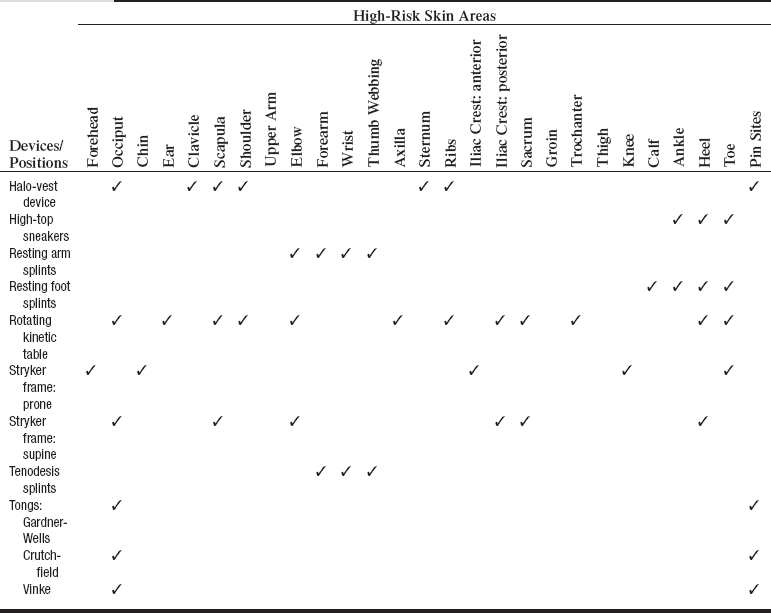

• Once the traction is in place, the patient is maintained on strict bed rest. For facilitation of turning, the patient may be placed on a special bed or turning frame (Fig. 100-1).

• The principles of skeletal traction are the foundation of management of any patient in cervical traction. One must follow such key points as (1) never raising the traction weights, (2) never disconnecting the traction, (3) never allowing the traction weights to rest on the floor, and (4) never allowing other objects to compromise freely hanging weights.

EQUIPMENT

PATIENT AND FAMILY EDUCATION

• Explain the procedure and the reason for the traction.  Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased.

Rationale: Patient and family anxiety may be decreased.

• Explain the patient’s role in maintaining the traction.  Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited.

Rationale: Patient cooperation is elicited.

• Explain how the patient’s basic needs will be met during the confinement to bed and the maintenance of traction.  Rationale: The patient and family are reassured that the patient will be cared for and his or her needs met.

Rationale: The patient and family are reassured that the patient will be cared for and his or her needs met.

PATIENT ASSESSMENT AND PREPARATION

Patient Assessment

• Conduct a complete neurologic assessment that includes motor strength of the major muscles, sensory function (assess light touch, pain, and proprioception. Note the highest dermatome level with impaired sensation.) Assess deep tendon reflexes (biceps, triceps, patellar, and Achilles), superficial reflexes, and cranial nerves.  Rationale: Baseline data are established for determination of any change in neurologic function.

Rationale: Baseline data are established for determination of any change in neurologic function.

• Assess the patient’s comfort.  Rationale: Spinal injuries are often painful. Changes in pain in the head or neck or at the pin sites may suggest misalignment, pin site infection, or slippage of traction.

Rationale: Spinal injuries are often painful. Changes in pain in the head or neck or at the pin sites may suggest misalignment, pin site infection, or slippage of traction.

Patient Preparation

• Ensure that the patient and family understand preprocedural teaching. Answer questions as they arise, and reinforce information as needed.  Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

Rationale: Understanding of previously taught information is evaluated and reinforced.

• Verify correct patient with two identifiers.  Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

Rationale: Prior to performing a procedure, the nurse should ensure the correct identification of the patient for the intended intervention.

• Ensure that body alignment is maintained and that the patient is positioned in the middle of the bed.  Rationale: Positioning facilitates comfort and even distribution of the traction.

Rationale: Positioning facilitates comfort and even distribution of the traction.

• Check the orthopedic traction frame, rope knot, and pulley or cable and bracket alignment device for secure attachment and function.  Rationale: Ineffective traction or loss of traction may result in loss of realignment and stabilization of the vertebral column, resulting in spinal cord injury.

Rationale: Ineffective traction or loss of traction may result in loss of realignment and stabilization of the vertebral column, resulting in spinal cord injury.

• Check the ropes and weights to be sure that they are hanging freely. Check the cable and alignment bracket device for patients treated on a kinetic therapy bed.  Rationale: Assessment maintains function and prevents slippage of the orthopedic equipment.

Rationale: Assessment maintains function and prevents slippage of the orthopedic equipment.

References

1. Blissitt, PA. Spinal cord injury. In: Carlson KK, ed. -Advanced critical care nursing. Philadelphia: -Saunders/Elsevier; 2009:637–680.

2. Consortium for Spinal Cord Medicine, Early acute management in adults with spinal cord injury. a clinical -practice guideline for health-care professionals. Paralyzed Veteran’s Association, -Washington, DC, 2008.

3. Gupta MC, Benson, DR, Keenen, TL. Initial evaluation and emergency treatment of the spine-injured patient. In: Browner BD, Green NE, Jupiter JB, et al, eds. Skeletal trauma. ed 4. Philadelphia: Saunders; 2008:794–798.

![]() 4. Harvey, CV, Challenges of traction in critical care. a case study. Crit Care Nurs Q 1998; 21:1–13.

4. Harvey, CV, Challenges of traction in critical care. a case study. Crit Care Nurs Q 1998; 21:1–13.

5. Lethaby, A, Temple, J, Santy, J. Pin site care for preventing infections associated with external bone fixators and pins. Cochrane Database of Syst Rev. 2008; 4:CD004551.

![]() 6. Osmond, T, Clinical update. principles of traction. Aust Nurs J 1999; 6:S1–S4.

6. Osmond, T, Clinical update. principles of traction. Aust Nurs J 1999; 6:S1–S4.

![]() 7. Patterson, MM. Multicenter pin care study. Orthop Nurs. 2005; 24:349–360.

7. Patterson, MM. Multicenter pin care study. Orthop Nurs. 2005; 24:349–360.

![]() 8. Styrcula, L, Traction basics. part I. Orthop Nurs 1994; 13:71–74.

8. Styrcula, L, Traction basics. part I. Orthop Nurs 1994; 13:71–74.

9. Wood, G. Cervical spine injuries. In: Canale ST, Beaty JH, eds. Campbell’s operative orthopaedics. ed 11. St Louis: Mosby; 2008:1761–1810.

10. Wuermser, LA, Ho, CH, Chiodo, AE, et al, Spinal cord injury medicine. 2acute care management of traumatic and nontraumatic injury. Arch Phy Med Rehabil 2007; 88 :S55–S61.

Hickey, JV. Vertebral and spinal cord injuries. In: Hickey JV, ed. The clinical practice of neurological and neurosurgical nursing. ed 6. Philadelphia: Wolters Kluwer Health/Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2009:410–453.

Sponseller, PD, Takenaga, RK, Newton, P, et al. The use of traction in the treatment of severe spinal deformity. -Spine. 2008; 33:2305–2309.