CHAPTER 31 Lid–cheek blending: the tear trough deformity

History

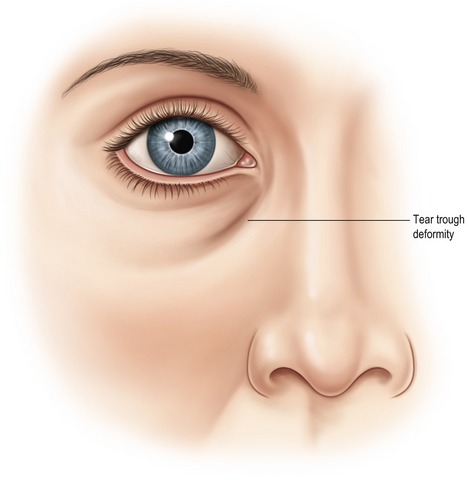

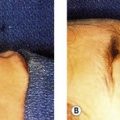

While traditional lower lid blepharoplasty has been performed in order to improve the periorbital region, the tear trough deformity should be considered a separate anatomical subunit of the lower periorbital aesthetic unit. One of the unique aspects of the tear trough deformity is that while it may be age related, the dark appearing groove associated with the deformity is often present in young patients with no other signs of periorbital aging (Fig. 31.1). The “tear trough deformity” was reportedly first named by Flowers in 1969 when he “[noticed] how a shed tear often tracks the course of this groove…” Flowers also credited Loeb who earlier, in 1961, adopted the descriptive term “nasojugal groove” from the ophthalmology literature by Duke-Elder. During the decade that followed, the terms became synonymous and both Loeb and Flowers published elegant surgical techniques aimed at correction of the deformity. Since it became apparent that fat removal was not successful at correcting the tear trough deformity, techniques evolved which were specifically aimed at correction of the tear trough deformity. Early techniques by Loeb in 1981 included fat pad sliding and fat grafting, while Flowers used orbicularis muscle plication, fat translocation, and subgaleal grafts. Disappointment with resorption of autogenous grafts led Flowers to develop alloplastic tear trough implants by 1993.

Physical evaluation

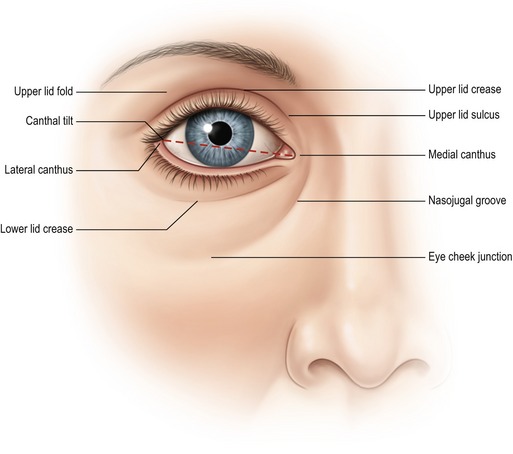

• Eyelid shape: relationship of the lower lid to the inferior corneoscleral limbus and the lid tilt based on the relationship of the lateral canthus and medial canthus (Fig. 31.2).

• Orbital morphology: vector analysis to determine morphologically prone eye, positive and negative vector, and Hertel exophthalmometry to determine globe prominence.

• Lower lid tone: lid snap back and lid distraction to evaluate orbicularis tone and tarsoligamentous laxity.

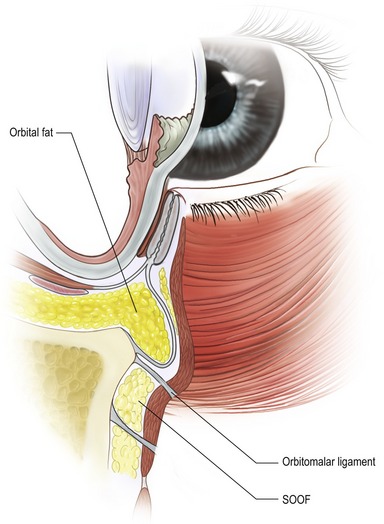

• Volumetric analysis: evaluation of excess skin, muscle and orbital fat with emphasis on the lid–cheek junction defined by the orbitomalar ligament and tear trough deformity, retropulsion of orbital fat.

• Midfacial aging: the presence of descent of the SOOF (suborbicularis oculi fat), malar fat pad, or the presence of malar bags or festoons.

• Skin analysis: evaluation of photoaging of the periorbital region including loss of elasticity, rhytids, and hyperpigmentation.

• Tear analysis: history of dry eyes, contact lens intolerance, and performance of Schirmer’s test for tear production.

Anatomy

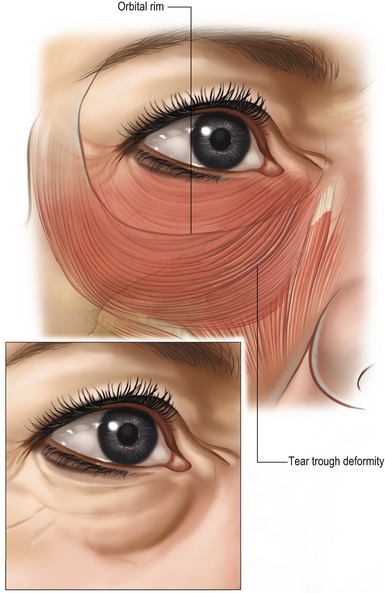

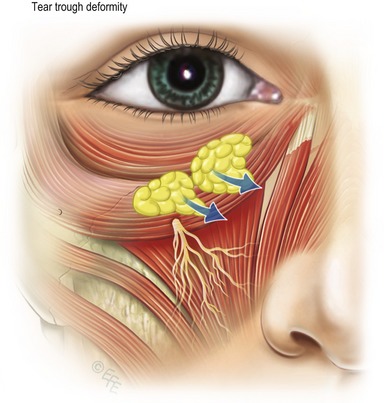

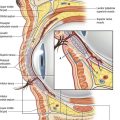

Flowers described the tear trough deformity as the triangular shaped defect between the angular head of the quadratus labii superioris muscle and the orbicularis muscle. There is often associated deficiency of the infraorbital rim which Rees described as bony deficit below the normal rim or suborbital hypoplasia. The presence of excess orbital fat often disguises the tear trough deformity and distracts the surgeon’s attention. Since removal of excess orbital fat does not correct the tear trough, simulation of fat removal with retropulsion of the fat superiomedial to the tear trough clearly defines the anatomy of the defect. The defect can be considered a depression bordered by orbital portion of the orbicularis oculi, the levator labii superioris, levator alaeque nasi muscles (Fig. 31.3). Since there is little subcutaneous tissue between the skin and the orbicularis muscle, the tear trough is comprised of thin skin at the junction of eyelid, nasal and cheek skin with attenuated subcutaneous tissue overlying the maxilla. The tear trough can therefore be considered a defect of the anterior lamella with underlying bony contributions. The formation of the tear trough deformity is often one of the first signs of aging around the eyes. The concavity in the nasojugal groove is often associated with apparent fat herniation above or it may present independently. There is individual variation in depth and morphology of the tear trough and periorbital hollows along the rim. In order to devise the optimal correction for the tear trough, understanding the anatomy of this area is critical.

The orbicularis oculi muscle has a direct attachment to the inferior orbital rim from the anterior lacrimal crest to the medial limbus or approximately 30% of the length of the rim. Lateral to this, the attachment to the bone is via the orbicularis retaining ligaments (ORL) which have variable length at different points along the inferior orbital rim. The length increases to a maximum centrally and then decreases laterally until the ORL merges with the lateral orbital thickening in the lateral canthal region. The levator labii superioris originates just below the orbicularis oculi muscle attachment to the medial orbital rim (Fig. 31.4). It is along the attachment of the orbicularis oculi muscle to the orbital rim that the tear trough deformity first manifests as a concavity that gets deeper with time. The tear trough deformity is at the inferior orbital rim most medially but very quickly falls below the rim, with the maximal distance from the rim occurring centrally. The hollowing can continue laterally in more advanced aging, presenting at or just below the orbital rim, where the retaining ligaments are thicker and less distensible.

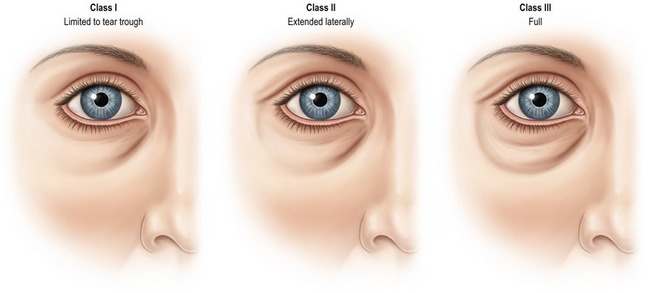

Clinically, the periorbital pattern of volume loss is categorized into three classes. Class I is limited to the tear trough or medial orbit. These patients sometimes show very mild flattening of the central area along the orbital rim in a reverse triangular pattern. Class II patients exhibit volume loss laterally as well as medially and they may have mild volume deficiency in the medial cheek and mild flattening of the central triangle. Class III patients exhibit a depression circumferentially along the orbital rim in a full and continuous pattern of hollowing medially to laterally (Fig. 31.5). This pattern is often associated with more advanced volume deficiency in the medial cheek, central reverse triangle, and malar eminence as well as demonstrating an oblique cheek crease highlighting the malar bags superiorly. The depth of the tear trough is used to estimate the volume required for correction with injections. Deeper and more extended patterns of volume loss (Classes II and III) can be associated with relative medial cheek/midface flattening, malar volume loss, as well as possible volume loss in the temporal region, brow and lower face.

Technical steps

Surgical correction of the tear trough deformity

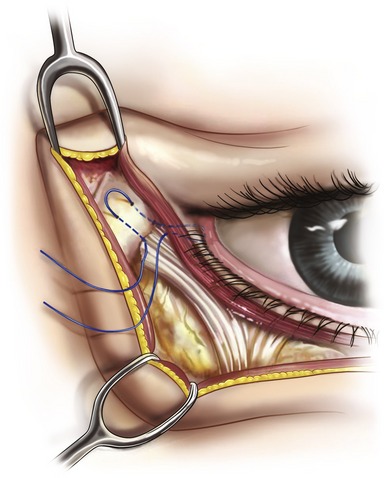

The lid–cheek junction is addressed by volume redistribution of the orbital fat combined with muscular release of the tear trough, ligamentous release of the orbitomalar ligament, and vertical elevation of the orbicularis oculi (Fig. 31.6). The initial release of the orbitomalar ligament is performed with supraperiosteal dissection along the semicircle of the infraorbital rim from lateral canthus to the level of the infraorbital nerve. Care is taken to preserve the zygomaticofacial and infraorbital sensory nerves. Approximately 10 mm of inferior dissection is performed in order to release the orbitomalar ligament and elevate the SOOF with the skin muscle flap. Superior elevation of the SOOF and inferior transposition of the orbital fat across the rim create anatomical blending of the orbital and midfacial fat compartments. Rather than using the septum to accomplish this, subtotal septectomy is performed to reduce the risk of postoperative septal scarring and to allow the two separate fat compartments to merge. For more advanced midfacial aging, malar fat pad descent and malar bags, a more extensive subperiosteal midface lift may be performed.

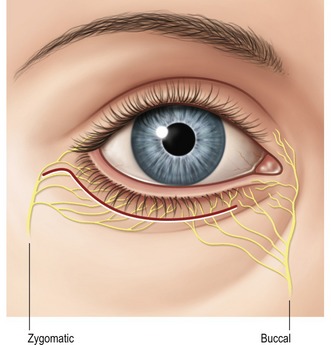

The central and lateral fat compartments are sutured with 6-0 Vicryl to the preserved periosteum below the rim to cover the infraorbital rim and add volume to the suborbital deficiency. Additional dissection of the tear trough is required in order to transpose the central and medial fat pads into the nasojugal groove. An insulated Desmarre retractor is used to expose the medial orbital rim to the level of the anterior nasolacrimal crest. Careful release of the origin of the orbital orbicularis oculi from the orbital rim is performed with low power electrocautery superficial to the periosteum. Dissection continues for 5 mm until the muscular triangle of the tear trough deformity is reached to create the pocket for fat transposition. The ligamentous attachments of the anterior lamella overlying the tear trough are released. Dissection should be limited in order to avoid injury to the buccal branch of the facial nerve which is medial to the tear trough at the level of the angular artery (Fig. 31.7). Stimulation of the levator labii or alaeque nasi with the electrocautery causes twitching of the upper lip and should be considered a sign of overdissection.

Once the tear trough has been released, the nasal fat pad is transposed into the muscular triangle and sutured to the periosteum with 6-0 Vicryl (Fig. 31.8). Additional volume can be added by suturing a portion of the central fat pad taking care to avoid traction on the inferior oblique muscle. While ligamentous release and volume enhancement are key aesthetic principles of the procedure, tightening the anterior lamellae in a superolateral vector is the final step of the technique. In order to safely perform this step, the principles of separate points of bony fixation for the anterior and posterior lamellae respectively are followed. A lateral canthopexy is performed using a 4-0 double armed Mersilene suture placed through the tarsal plate and lateral retinaculum which is then anchored to the periosteum of the lateral orbital rim at the preoperative level of the lateral canthus which is most commonly at the level of the pupil (Fig. 31.9). Positioning of the lateral canthopexy suture is important in order to prevent complications and preserve preoperative eyelid shape. Following lateral canthopexy, the skin muscle flap is elevated as the orbicularis is sutured to the lateral orbital rim periosteum. Multiple points of orbicularis suspension with 4-0 Vicryl are performed in order to achieve the desired aesthetic result while minimizing the risk of lid retraction from anterior lamella scarring in the postoperative period. Conservative skin removal along the lid margin is also important in order to minimize the risk of complications and the skin is closed with 6-0 fast absorbing sutures.

Non-surgical correction of the tear trough deformity

Hyaluronic acid for correction of the tear trough deformity

Hyaluronic acid has the advantages of gel consistency and favorable flow characteristics, easy availability, and reversibility which make it preferable to fat for the tear trough. The longevity of the effect in this area is acceptable with the stability up to six months on average followed by a slow decrease during the second six months. While patients are informed that the correction lasts approximately 12 months, it is not uncommon to have lasting effect up to two years in some patients. The best candidates are Class I patients with good skin tone and minimal skin laxity with minimal tear troughs and periorbital hollowing. This procedure has excellent utility in post-surgical patients who have an uncorrected tear trough or overresected orbital fat. In addition to the tear trough, injection may be required in the central reverse triangle and the malar eminence. The areas to be treated are marked prior to the procedure to outline a road map for the injections.

Small volumes, approximately 0.01–0.05 ml, of hyaluronic acid are delivered using a sterile 30 G  inch stainless steel blunt cannula introduced through a 25 G needle hole along the orbital rim as marked (Fig. 31.10). Alternatively, a 30 or 32 G needle can be utilized. The injections should be deep just superficial to the periosteum and deep, to the orbicularis oculi. Centrally, the orbitomalar ligaments are longer so the injection is performed in the deep subcutaneous plane. Hyaluronic acid is injected discontinuously in the deformity medial to lateral, while withdrawing the cannula. In order to minimize bruising, blunt release of the ligaments with the needle is not recommended. Typically 2–3 entry sites are used medially and centrally, and 1–2 entry sites are used laterally. Gentle massage is performed after the delivery, as needed, to disperse the filler in the intended location. Since there is little early resorption of hyaluronic acid, overcorrection is not performed. In specific instances, very superficial subdermal injection using a 32 G needle is performed to “lift” the overlying skin. This is usually a “spot’ application over a 1 or 2 mm surface area.

inch stainless steel blunt cannula introduced through a 25 G needle hole along the orbital rim as marked (Fig. 31.10). Alternatively, a 30 or 32 G needle can be utilized. The injections should be deep just superficial to the periosteum and deep, to the orbicularis oculi. Centrally, the orbitomalar ligaments are longer so the injection is performed in the deep subcutaneous plane. Hyaluronic acid is injected discontinuously in the deformity medial to lateral, while withdrawing the cannula. In order to minimize bruising, blunt release of the ligaments with the needle is not recommended. Typically 2–3 entry sites are used medially and centrally, and 1–2 entry sites are used laterally. Gentle massage is performed after the delivery, as needed, to disperse the filler in the intended location. Since there is little early resorption of hyaluronic acid, overcorrection is not performed. In specific instances, very superficial subdermal injection using a 32 G needle is performed to “lift” the overlying skin. This is usually a “spot’ application over a 1 or 2 mm surface area.

Postoperative care

The postoperative care for the tear trough procedure is similar to routine care following lower blepharoplasty. Liberal use of icepacks for the first 24–48 hours and ophthalmic ointment and drops to prevent corneal dryness during the first postoperative week should be performed. In addition, in order to minimize bruising and swelling, postural elevation, avoidance of sodium, and perioperative arnica montana and bromelain are suggested. Sutures are removed at 5 days after surgery and the patient is allowed to resume limited activity with return to full activity by 2 weeks. Sunglasses and sunscreen are important to avoid periorbital hyperpigmentation and sun damage. Following injection to the tear trough, patients are instructed to use gentle digital pressure if areas of edema or irregularity persist after the first few days. Generalized massage is not recommended. Regular makeup, skin care can be resumed and camouflage makeup can be applied immediately. Cold packs in the hours following the procedure help reduce edema.

Complications

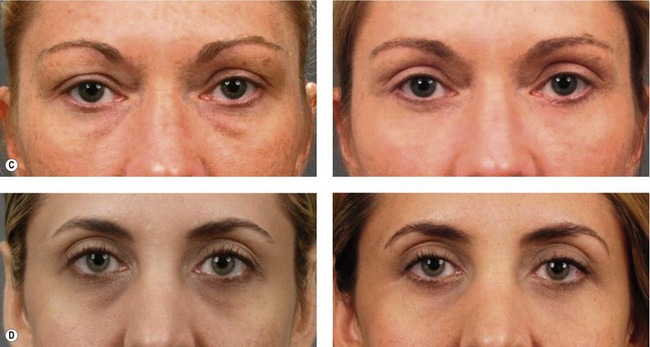

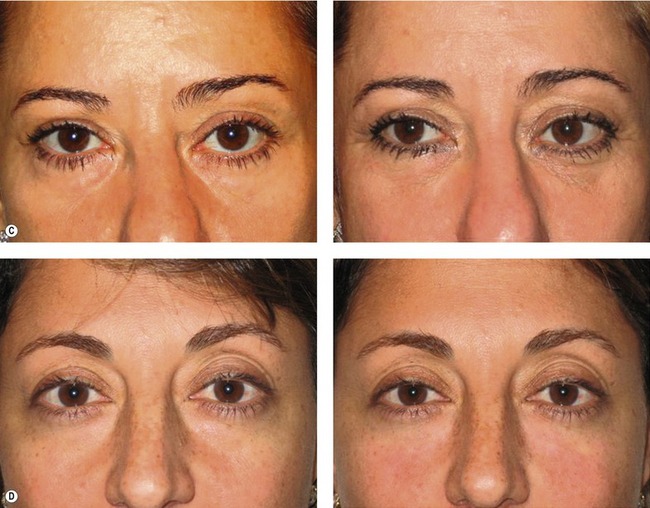

The most common complication following injection to the tear trough is ecchymosis which occurs in up to 50% of patients and is usually limited to injection sites. Variable but subtle edema is not uncommon with resolution by 2–3 weeks. The most bothersome complication is visible surface irregularities or a blue color to the thin skin overlying the tear trough in some patients known as the Tyndall effect. Patients who are professionally photographed may have skin surface deformities which are only visible temporarily during flash photography and should be forewarned. Overall, the complication rates associated with non-surgical and surgical management of the tear trough procedure have been very acceptable. The aesthetic results which can be achieved represent a significant improvement compared to traditional methods of lower blepharoplasty with the clear advantage of blending the lower lid and the cheek thereby creating a more youthful and naturally shaped eyelid (Figs 31.11, 31.12).

Pearls & pitfalls

• Tear trough deformity, or nasojugal groove, is a common periorbital abnormality occurring in up to 40% of patients who present for blepharoplasty.

• Traditional techniques of lower blepharoplasty with fat removal may actually make the tear trough deformity worse.

• The tear trough deformity can be improved with non-surgical technique of injections with hyaluronic acid or autologous fat.

• Care should be taken to inject very small aliquots of filler directly on the periosteum underlying the tear trough and orbital rim.

• Overcorrection with fillers may result in visible contour deformities and surface irregularities which are difficult to correct.

• Hyaluronidase can be used to correct excess hyaluronic acid and dilute kenalog or needle aspiration can be used to correct excess fat injections.

• Surgical correction with the tear trough procedure blends the lid–cheek junction through release of the ligamentous attachments and fat transposition.

• Overdissection in the nasojugal area may result in injury to the buccal branch of the facial nerve.

• Lateral canthopexy and conservative skin removal are important in order to minimize the risk of postoperative lid malposition.

Summary of steps

1. Surgical correction: The goal of correction of the tear trough deformity utilizes an anatomical approach by adding volume to the soft tissue deficiency. The technique should be considered an adjunct to standard lower blepharoplasty.

2. The technique should be performed on an individualized basis rather than as a routine part of lower blepharoplasty.

3. Correction of the tear trough deformity and blending the lid–cheek junction can be performed in a less invasive manner through the use of fillers.

4. The tear trough procedure is performed utilizing an open transcutaneous lower blepharoplasty approach in order to address all of the anatomical changes in the periorbital region including the anterior and posterior lamella.

5. The lid–cheek junction is addressed by volume redistribution of the orbital fat combined with muscular release of the tear trough, ligamentous release of the orbitomalar ligament, and vertical elevation of the orbicularis oculi.

6. For more advanced midfacial aging, malar fat pad descent and malar bags, a more extensive subperiosteal midface lift may be performed.

7. The central and lateral fat compartments are sutured with 6-0 Vicryl to the preserved periosteum below the rim to cover the infraorbital rim and volume to the suborbital deficiency. Additional dissection of the tear trough is required in order to transpose the central and medial fat pads into the nasojugal groove.

8. Non-surgical correction of the tear trough deformity: Prior to the advent of injectable hyaluronic acid, autologous fat was the best filler for the periorbital region. Fat remains a useful tool for volume augmentation in patients with thick overlying skin and good elasticity with generalized orbital volume deficiency.

9. Fat transfer for correction of the tear trough deformity: Our preferred technique consists of transfer of very small amounts of autologous fat in multiple passes and over multiple sessions, if necessary, without significant overcorrection at each transfer.

10. Hyaluronic acid for correction of the tear trough deformity: Small volumes, approximately 0.01–0.05 mL, of hyaluronic acid are delivered using a 30 G  inch stainless steel blunt cannula or needle along the orbital rim.

inch stainless steel blunt cannula or needle along the orbital rim.

Barton FE, Ha R, Awada M. Fat extrusion and septal reset in patients with the tear trough triad: A critical appraisal. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2004;113:2115–2121.

Coleman S. Avoidance of arterial occlusion from injection of soft tissue fillers. Aesthet Surg J. 2002;22:555–557.

Coleman SR. Facial recontouring with lipostructure. Clin Plast Surg. 1997;24:347–367.

Flowers RS. Tear trough implants for correction of tear trough deformity. Clin Plast Surg. 1993;20:403–415.

Goldberg RA. Transconjunctival orbital fat repositioning: Transposition of orbital fat pedicles into a subperiosteal pocket. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:743–748.

Hamra ST. Arcus marginalis release and orbital fat preservation in midface rejuvenation. Plast Reconstr Surg. 1995;96:354–362.

Hester TR, Codner MA, McCord CD, Nahai F, Giannopoulos A. Evolution of technique of the direct transblepharoplasty approach for the correction of lower lid and midfacial aging: Maximizing results and minimizing complications in a 5-year experience. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2000;105:393–406.

Hirmand H. The tear trough and hyaluronic acid: Is it a happy union? Presentation at the Aesthetic Meeting 2005, Annual Meeting of ASAPS, New Orleans, LI, April 2005.

Kane MA. Treatment of tear trough deformity and lower lid bowing with injectable hyaluronic acid. Aesthet Plast Surg. 2005;29:363–367.

Kawamoto HK, Bradley JP. The tear “TROUF” procedure: Transconjunctival repositioning of orbital unipedicled fat. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2003;112:1903–1907.

Loeb R. Fat pad sliding and fat grafting for leveling lid depressions. Clin Plast Surg. 1981;8:757–776.

Rees TD, Dupuis CC. Baggy eyelids in young adults. Plastic Reconstr Surg. 1969;43:381–387.

Zide BM. Surgical anatomy around the orbit. Lippincott: Williams and Wilkins; 2006.