14 Glabella/central brow

Summary and Key Features

• Soft tissue augmentation of the glabella and central brow is increasingly recognized as an important part of the pan-facial volumization strategy for many patients

• Augmentation of the glabella and central brow with fillers may be performed to correct age-related volume loss, or for the purposes of enhancement

• The glabella and central brow are anatomically unforgiving with regard to both safety and aesthetic considerations

• An understanding of anatomy and the physicochemical characteristics of fillers (including rheology) drives the selection of appropriate filler products and safe, efficacious injection techniques

• For many patients, the combination of fillers with neuromodulators will produce more a natural-looking rejuvenation than treatment with neuromodulators alone

• Fillers are also of value for patients with residual rhytides after neuromodulator treatment of the glabella and central brow

• A thorough pre-procedural consultation and discussion of realistic objectives are key to optimizing patient satisfaction

• Superficial or deep injection approaches may be employed alone or in combination. For both approaches, hyaluronic acid fillers may be the best option owing to their potential reversibility and excellent safety margin

• Meticulous sterile technique is essential before and during all filler injection procedures to minimize the risk of infection or biofilm.

• When properly performed, filler injections to the glabella and brow have a high rate of patient satisfaction and can profoundly improve the aesthetic appearance of the whole face

Epidemiology and patient selection

1. Patients with residual rhytides following neuromodulator injections. These patients, who generally have some degree of volume loss and decreased skin elasticity, can be identified in advance of neuromodulator injection to the glabella and central brow with a skin stretch test, and counseled at that time regarding the likely need for adjunctive filler. Filler can correct volume loss and compensate to some extent for loss of skin elasticity.

2. Patients who prefer to retain some degree of glabellar and central brow mobility after neuromodulator treatment. Neuromodulator dosing strategies for the glabella and forehead, including the central brow, vary depending on patient preference for a mobile versus a ‘frozen’ look. Patients who wish to retain maximum expressivity and avoid a ‘frozen’ look may be best treated with relatively low doses of neuromodulators to the glabella and forehead, including the central brow, plus adjunctive filler.

3. Patients with volume loss from the glabella and forehead, including the central brow. Glabellar volume loss often assumes the form of two parallel vertical furrows of variable depth. In the forehead including the central brow, volume loss may be focal or more general, respectively resulting in localized or more diffuse, trough-like concavities. Volume loss to the glabella is generally primary and age related. Volume loss to the central brow may also be primary, or secondary to neuromodulator-related atrophy of the frontalis. This is a thin sheet-like muscle and this author has observed anecdotally that it has a propensity to develop atrophic areas in some patients after repeated neuromodulator injections over many years, especially if these injections are of high dosage.

4. Patients desiring augmentation or enhancement of forehead / central brow convexity. There are individual and cultural / ethnic variations in the preference for a convex or even domed forehead. Forehead augmentation has become especially popular in Korea and other Asian countries. It is interesting to note that neuromodulator treatment of the upper face, the most popular non-surgical rejuvenative procedure in the USA, is rarely performed on patients in these countries because they do not tend to frown in the way that Caucasians do.

5. Patients who decline neuromodulator treatment but still wish to improve rhytides in the glabella and central brow regions.

Anatomical considerations

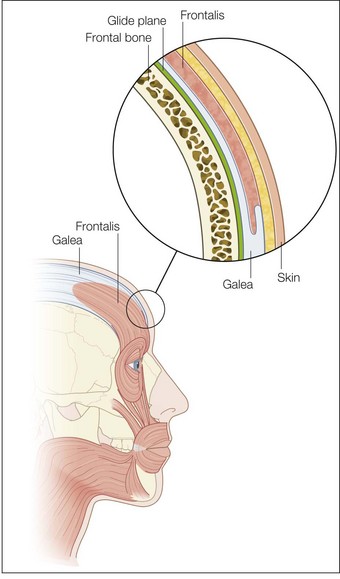

The most superficial tissue plane of the glabella and central brow is the skin, comprising the epidermis and dermis. Beneath this lies the subcutaneous tissue, then the superficial fascia, which covers the underlying muscles. There is loose subgaleal areolar tissue below the muscles, then the periosteum, which represents the deep fascia in this region and rests upon the bone (Fig. 14.1).

Decision-making: selection and preparation of filler product, selection of injection plane

General considerations

An understanding of structural and functional anatomy and of the physicochemical characteristics of fillers – including the flow-related (rheologic) properties of elasticity (G prime) and viscosity that predict their behavior – informs the selection of appropriate filler products and injection techniques to achieve optimal results (see Box 14.1, Tables 14.1 and 14.2; see also Figs 14.2–14.6).

Box 14.1

Soft tissue fillers currently approved by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA), under study in the U.S.

Selection of injection plane and filler product

Fillers may be injected into the glabella and the central brow via two approaches: deep and superficial. These approaches may be used alone, or in combination with a multiplane or ‘sandwich’ technique. As discussed below, blunt microcannulas or sharp needles may be employed for filler injection. Filler may be injected with anterograde technique, tracking a path ahead of the injecting cannula or needle, or with retrograde technique, flowing along the path already created by the cannula or needle as it is withdrawn through the tissue (Sundaram H, Monheit G et al).

Deep approach

Desirable physical characteristics of a filler product for the deep approach to the glabella and forehead, including the central brow, include medium to low viscosity – for some degree of spread to decrease the risk of contour irregularities – and some lifting capacity, as measured by elastic modulus or G prime. A medium- or low-viscosity product such as Belotero® Balance; Juvéderm® Voluma, Ultra Plus or Ultra; or Prevelle® Silk may be selected. Alternatively, a higher viscosity product such as Perlane® or Restylane® may be diluted to lower its viscosity. Juvéderm® Voluma is currently under study in the US, but is available in Canada, Europe and elsewhere. It is described as having some tissue spread and integration but also significant cohesivity that confers robustness and moldability (Carruthers J, Carruthers A et al). These properties, together with the presence of some particles of varying shape and size (Stocks D, Sundaram H et al), make it appropriate for deep volumization in the pre-periosteal tissue plane. Other products available outside the USA that are appropriate for deep implantation into the glabella and brow include a cohesive polydensified matrix HA (Belotero® Intense, Merz) and a HA with “optimal balance” technology that has the largest gel calibration (particle size) and heaviest crosslinking within its product family (Emervel® Volume, Galderma). In addition to the absolute values of elasticity (firmness) and viscosity (spread) for each filler product, it is also useful to consider the balance of elasticity versus fluidity. This can be done with a rheologic value known as tan delta, which is calculated as the viscosity modulus (G double prime or G”) divided by the elasticity modulus (G prime or G’). [FIG. 14.4] Juvéderm Voluma, Perlane and Restylane have a low tan delta, and thus are more elastic than fluid and suited to deep implantation for contouring. Belotero Balance has a high tan delta, indicating a preponderence of fluidity over elasticity that makes it suitable for flowing through the superficial tissue planes. (Sundaram H, Flynn T et al.)

Superficial approach

Desirable physical characteristics of a filler for the superficial approach include low viscosity so that the filler spreads significantly, decreasing the risk of contour irregularities in these very anatomically unforgiving tissue planes. The filler must also not cause the Tyndall effect (more accurately known as Rayleigh scattering), which is the phenomenon whereby the particles within a bolus of superficially implanted HA filler scatter light back to the observer’s eye. Scattering is inversely proportional to the 4th power of the light wavelength; therefore blue light, which has a shorter wavelength, is scattered more and this imparts a bluish discoloration to the filler bolus. It has been demonstrated that both the Perlane® / Restylane® and Juvéderm® families of HA products have a significant particulate component and are therefore best suited to subdermal implantation when undiluted (Stocks D, Sundaram H et al).

Injection technique

At follow-up 3 weeks later, the patient is very pleased with her results (Figure 14.7A and B).

Post-procedural course and recovery

Patients can usually return to normal daily activities immediately.

Tips for maximizing patient satisfaction

A detailed pre-treatment consultation and discussion of realistic expectations are prerequisites for patient satisfaction.

A detailed pre-treatment consultation and discussion of realistic expectations are prerequisites for patient satisfaction.

Selection of the appropriate filler product and tissue plane for injection.

Selection of the appropriate filler product and tissue plane for injection.

Meticulous injection technique with avoidance of overcorrection.

Meticulous injection technique with avoidance of overcorrection.

Re-evaluation of the patient for results and satisfaction 2–4 weeks after injection. Patient concerns including undercorrection or overcorrection can be addressed at this follow-up visit.

Re-evaluation of the patient for results and satisfaction 2–4 weeks after injection. Patient concerns including undercorrection or overcorrection can be addressed at this follow-up visit.

For many patients, results will be optimized by combining fillers with neuromodulators. Better results may be achievable with sequential treatment to the same area; however, this must be balanced with the convenience to patients of same-day treatment. For some patients, differential placement of fillers and neuromodulators will yield the best results (e.g. filler to the central brow and neuromodulator to the glabella).

For many patients, results will be optimized by combining fillers with neuromodulators. Better results may be achievable with sequential treatment to the same area; however, this must be balanced with the convenience to patients of same-day treatment. For some patients, differential placement of fillers and neuromodulators will yield the best results (e.g. filler to the central brow and neuromodulator to the glabella).

Borrell M, Leslie D, Tezel A. Lift capabilities of hyaluronic acid fillers. Journal of Cosmetic and Laser Therapy. 2011;13:21–27.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A. Volumizing the glabella and forehead. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:S1905–S1909.

Carruthers J, Glogau R, Blitzer A. Advances in facial rejuvenation: botulinum toxin type A, hyaluronic acid dermal fillers, and combination therapies – consensus recommendations. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2008;121(5):5S–30S.

Carruthers J, Carruthers A, Tezel A, et al. Volumizing with a 20-mg/mL smooth, highly cohesive, viscous hyaluronic acid filler and its role in facial rejuvenation therapy. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:S1886–S1892.

Fang F, Clapham P. A systematic review of interethnic variability in facial dimensions. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;127(2):874–881.

Flynn T, Sarazin D, Bezzola A, et al. Comparative histology of intradermal implantation of mono and biphasic hyaluronic acid fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2011;37:637–643.

Hanke CW, Rohrich R. Facial soft-tissue fillers: assessing the state of the science conference – proceedings report. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;64(4):S53–S65.

Kang M, Park E, Shin HS, et al. Skin necrosis of the nasal ala after injection of dermal fillers. Dermatologic Surgery. 2011;3637:3375–3380.

Lambros V. The use of hyaluronidase to reverse the effects of hyaluronic acid filler. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2004;114(1):277.

Requena L, Requena C, Christensen L, et al. Adverse reactions to injectable soft tissue fillers. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology. 2011;64(1):1–34.

Rohrich R, Monheit G, Nouven AT, et al. Soft tissue filler complications: the important role of biofilms. Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery. 2010;125(4):1250–1256.

Stocks D, Sundaram H, Michaels J, et al. Rheological evaluation of the physical properties of hyaluronic acid dermal fillers. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2011;10(9):974–980.

Sundaram H. Face value: the truth about beauty – and a guilt-free guide to finding it. Emmaus, PA: Rodale; 2003.

Sundaram H, Voigts B, Beer K, et al. Comparison of the rheological properties of viscosity and elasticity in two categories of soft tissue fillers: calcium hydroxylapatite and hyaluronic acid. Dermatologic Surgery. 2010;36:S1859–S1865.

Sundaram H, Weinkle S, et al. Blunt injection microcannulas: a consensus document. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2012. March

Sundaram H, Flynn T, Cassuto D, et al. New and Emerging Concepts in Soft Tissue Fillers. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2012;11(8):s12–s25.

Sundaram H, Kiripolsky M 2012 Non-Surgical Rejuvenation of the Upper Eyelid and Brow in Clinics in Plastic Surgery [Elsevier, in press]

Sundaram H, Monheit G, Goldman M, et al. Clinical Experiences with Hyaluronic Acid Fillers. Journal of Drugs in Dermatology. 2012;11(3):s15–s27.

-inch (12 mm) needle inserted perpendicular to the skin surface is effective for glabellar or brow lines. Skin blanching may be observed as microaliquots of filler are implanted intradermally. Retrograde serial threading with a 30 G 12 mm or longer needle may be preferred for more trough-like volume deficits, allowing the needle to dissect tunnels in the desired plane into which filler is then placed. Fanning injection at an angle to the trough may be more effective than injecting parallel to it. A longer needle, such as 30 G

-inch (12 mm) needle inserted perpendicular to the skin surface is effective for glabellar or brow lines. Skin blanching may be observed as microaliquots of filler are implanted intradermally. Retrograde serial threading with a 30 G 12 mm or longer needle may be preferred for more trough-like volume deficits, allowing the needle to dissect tunnels in the desired plane into which filler is then placed. Fanning injection at an angle to the trough may be more effective than injecting parallel to it. A longer needle, such as 30 G  inch (38 mm), permits more efficient fanning within the superficial plane. When the needle is fanning within the dermis, the angle of the needle hub to the skin is quite acute (30° or less) and skin tenting is seen. In the superficial dermis, the needle hub grazes the skin surface and the outline of the needle is clearly seen through the surface. Threading may confer a greater risk of ecchymosis than serial puncture, and patients should be apprised of this prior to treatment.

inch (38 mm), permits more efficient fanning within the superficial plane. When the needle is fanning within the dermis, the angle of the needle hub to the skin is quite acute (30° or less) and skin tenting is seen. In the superficial dermis, the needle hub grazes the skin surface and the outline of the needle is clearly seen through the surface. Threading may confer a greater risk of ecchymosis than serial puncture, and patients should be apprised of this prior to treatment.

-inch (12 mm) needle with retrograde serial threading and medial to lateral and lateral to medial oblique fanning approach into the dermis and subdermis of the glabella and central brow, while retracting the skin with the non-dominant fingers. The patient is periodically viewed during injection from above, below, and obliquely, to gauge the efficacy of volume correction. Tissue molding is performed after each injection. A total of 1 mL of the HA product is injected. You also inject the patient’s lower eyelids with 2 mL of a high concentration (20 mg/mL) cohesive polydensified HA filler (Belotero® Soft) to which you have added 0.3% lidocaine, using a 27 G 40 mm blunt microcannula for pre-periosteal and subdermal injection and a 30 G 12 mm (

-inch (12 mm) needle with retrograde serial threading and medial to lateral and lateral to medial oblique fanning approach into the dermis and subdermis of the glabella and central brow, while retracting the skin with the non-dominant fingers. The patient is periodically viewed during injection from above, below, and obliquely, to gauge the efficacy of volume correction. Tissue molding is performed after each injection. A total of 1 mL of the HA product is injected. You also inject the patient’s lower eyelids with 2 mL of a high concentration (20 mg/mL) cohesive polydensified HA filler (Belotero® Soft) to which you have added 0.3% lidocaine, using a 27 G 40 mm blunt microcannula for pre-periosteal and subdermal injection and a 30 G 12 mm ( -inch) sharp needle for intradermal injection. You inject her mid-face pre-periosteally and subcutaneously with 3 mL of calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse® ) to which you have added 0.3% lidocaine. The patient is pleased with her results and remarks that she looks younger and her nose now appears smaller.

-inch) sharp needle for intradermal injection. You inject her mid-face pre-periosteally and subcutaneously with 3 mL of calcium hydroxylapatite (Radiesse® ) to which you have added 0.3% lidocaine. The patient is pleased with her results and remarks that she looks younger and her nose now appears smaller.