52 Cancer of the Vulva

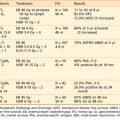

The middle third of the 20th century witnessed remarkable progress in the surgical treatment of vulvar cancer. During the 1940s and 1950s, radical vulvectomy, in continuity with bilateral inguinal, femoral, and selective pelvic lymphadenectomy, emerged as the standard for operative therapy and succeeded in more than doubling the cure rates previously obtained by less-comprehensive surgical strategies.1–4 Initially, this operation was accompanied by substantial risk of perioperative mortality as well as long, difficult periods of recuperation. Refinements in surgical technique, including primary closure of the perineal wound, shortened the duration of hospitalization and recovery. Reported at rates of 6% to 19% by the pioneers of radical vulvar surgery,2,5 total operative and perioperative deaths had declined to a rate less than 4% by the 1970s,6,7 and select patients with locally extensive disease were being treated by anterior, posterior, or total pelvic exenteration, with salvage rates exceeding 50% when regional nodes were found to be free of metastatic involvement.8 When inguino-femoral nodes were found to contain metastatic deposits, node dissection was often extended cephalad above the inguinal ligaments to encompass ipsilateral or bilateral pelvic lymphadenectomy. Radiation was infrequently used and largely restricted to palliative treatment. In retrospect, radiotherapy was administered using naive dose and fractionation schedules as well as techniques of limited sophistication.9–11 The late sequelae associated with excess dose to the vulva are shown in Figs. 52-1 and 52-2.

The past 35 years have witnessed a series of remarkable transformations in the treatment of this disease. Because of the success of radical vulvar surgery, substantial numbers of patients operated on and followed up on in large referral centers became available for the assessment of treatment outcomes, including chronic morbidities of surgical therapy. Leg lymphedema following radical groin and pelvic node dissection may be temporary, lasting a year or longer, or may be permanent, massive, and disabling.6,12 Pelvic relaxation, organ prolapse, and urinary incontinence can develop in some patients when removal of >1 cm of the distal urethra or a portion of the lower vagina is required. Significant vaginal introital stenosis can occur. Absence of the vulva and venereal fat can have the functional consequence of shortening the effective vaginal depth and removing a protective cushion from the pubic arch, contributing to dyspareunia in many patients. Clitorectomy will profoundly diminish capacity for arousal and climax. The psychosexual consequences of vulvectomy are frequently devastating.13–15

The clinical extent of vulvar cancer at the time of diagnosis may be decreasing, possibly because of enlightened attitudes toward the pathogenesis of the disease, diminished social stigma associated with the diagnosis, and improved access to health care resources. Among operable patients undergoing radical groin dissection, the frequency of lymph node metastasis fell from 50% to 60% at mid-century3,4 to 30% in surgical literature from the 1980s.16–20 Younger, sexually active patients are being diagnosed with preinvasive disease or unifocal disease of minimal volume and depth of invasion, often with regional nodes free of metastatic contamination.21 Modifications in the surgical approach to vulvar cancer have been provoked by concerns about the chronic morbidities of ablative surgery in patients with disease of limited extent. In select individuals, limited vulvar and groin surgery can accomplish equivalent cancer control as more extensive surgery, with less functional loss and mutilation.22–24 Judicious use of adjuvant postoperative radiation has reduced regional relapse, improved survival, and decreased the indications for pelvic lymphadenectomy.25

Planned in coordination with surgery of reduced extent, preoperative or postoperative radiation (often done with concurrent chemotherapy) has permitted salvage in patients who would otherwise have required exenterative surgery for cure, thus, preserving sexual, urinary, and anorectal function historically often sacrificed in the era of radical surgical monotherapy.26–39 Extrapolating from the success achieved in fashioning effective conservative therapy for patients with carcinoma of the anal canal, synchronous chemotherapy and radiation in reduced dose have accomplished curative nonsurgical management of some patients with massive, unresectable vulvar disease and of other patients judged too frail for extensive surgical intervention.40–43 A proliferation of management options now permits treatment responsibly tailored to the initial volume and extent of disease, the presence or absence of defined clinical and histopathologic prognostic factors, and the age, anatomy, personality, and priorities of the individual patient. This chapter reviews essential elements of these contemporary therapeutic strategies.

Epidemiology

Vulvar malignancies constitute less than 5% of female genital tract cancer, and only 1% to 2% of cancer in women. Historically, cancer of the vulva was most commonly observed in the seventh and eighth decades of life, with age-specific incidence rates in the United States rising steeply at age 70 and continuing to rise beyond age 80.44 Recent trends suggest that the average age of patients with vulvar cancer may be decreasing consequent to more common exposure to oncogenic serotypes of the human papilloma virus (HPV).45 The coincidence of vulvar intraepithelial neoplasia (VIN) or invasive squamous carcinoma of the vulva with in situ or invasive epidermoid carcinoma of the cervix has long been noted, and synchronous or sequential (usually antecedent) cervical lesions may be present in as many as 20% of women with primary vulvar lesions, suggesting a common etiology in at least some patients.46–52 Following conservative local excision, local-regional cancer regrowth, sometimes at anatomically distinct structures within conserved vulvar tissues and therefore plausibly representing metachronous appearance of independent primaries, lends credence to the so-called “field change” model of oncogenesis. Additional risk factors for the development of invasive vulvar cancer include a history of condyloma acuminatum, VIN, smoking, alcohol consumption, and chronic vulvar dystrophies, particularly lichen sclerosis.53–58

A rising incidence of VIN and reports of invasive vulvar cancer in young patients may reflect changing sexual mores and transmission of oncogenic serotypes of HPV. Detection of HPV in VIN or invasive disease is most common in young patients and is less frequent as a function of advancing age.58,59 The natural history of VIN is not well understood. Less than 10% of untreated VIN will progress to cancer with an average time to progression of 55 months.60 In general, VIN is treated with local excision. In contrast to surgical excision for invasive cancer, excision for VIN needs to be superficial only, to a depth of 1 mm in non–hair-bearing skin and 2 mm in hair-bearing skin (to include hair follicles which may be involved with VIN). Because VIN-3 may be associated with a clinically occult invasive component in up to 20% of cases,61 care must be exercised when employing treatment techniques, such as laser vaporization, which do not include full-thickness excision of the lesion. Recurrence rates after local excision depend on achieving negative surgical margins, as well as risk factors such as tobacco smoking and immunosuppression. Patients with multifocal recurrence or multiple metachronous recurrences may be treated with topical 5-fluorouracil (5-FU) cream or carbon dioxide (CO2) laser ablation rather than repeat local excisions. Patients infected with HIV are at particular risk for recurrent disease and may be treated with weekly prophylactic topical 5-FU cream.

Invasive vulvar cancer has been reported in young patients with both naturally occurring and iatrogenic immune compromise.62–66 Patients infected with HIV are more likely to have HPV infection than are HIV-uninfected women and may be more vulnerable to development of VIN than are HIV-negative controls. VIN may be more difficult to clear in HIV-infected women and may progress to invasive disease with greater rapidity.67,68 Recurrence rates for both VIN and invasive disease are higher in HIV-infected women.69

Vulvar carcinoma frequently coexists with vulvar dystrophy, particularly in older women.70,71 However, it is unknown whether lesions such as lichen sclerosis and typical or atypical hyperplastic dystrophy are true precursor lesions. Study of grossly normal genital skin and vulvar lichen sclerosis has revealed significantly higher degrees of single base instability in lichen sclerosis which may predispose to malignant transformation in some patients.72 Cancers in these older patients are less commonly associated with HPV infection, leading to the hypothesis that patients with vulvar cancer may be segregated into two broad groups: an older population with cancer arising in association with vulvar dystrophy and less likely to be associated with HPV, and a younger population with HPV-associated tumors frequently adjacent to areas of VIN.59,73

Anatomy

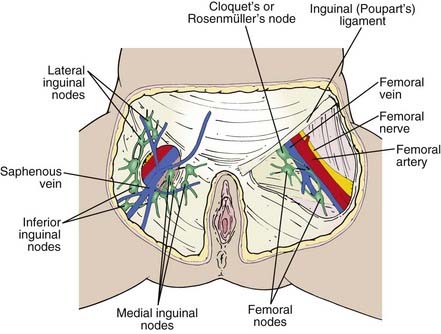

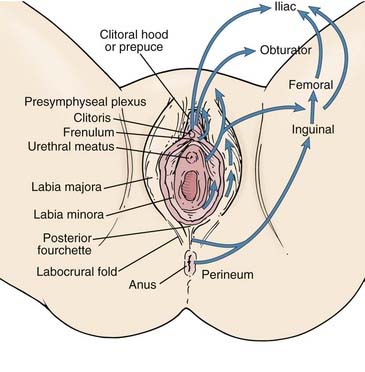

The vulva is composed of the mons veneris; labia majora; labia minora; clitoris, and vulvar vestibule, which harbors the urethral meatus and is bounded by the vaginal introitus (Fig. 52-3). The labia, limited laterally by the labiocrural folds, are the female analogue of the male scrotum and are pigmented and covered by hair lateral to the crests of the labia majora. Medially, the skin of the labia majora is smooth and hairless, with underlying sebaceous glands. Between the labia majora lie the hairless labia minora, whose medial skin also contains multiple sebaceous glands. Coursing posteromedially, the labia minora taper and join in a fold called the posterior fourchette. Anteriorly, the labia minora taper, then split to envelop the clitoris, fusing in front of the clitoris to form the prepuce (clitoral hood), and behind the clitoris to form the frenulum. The clitoris, an erectile organ analogous to the penis in the male, is composed of the glans and a body consisting of two corpora cavernosa that diverge into the two crura which lie attached to the undersurface of the pubic rami. The paired, mucus-secreting Bartholin glands lie deep to the posterior labia majora and drain by a simple duct lined by cuboidal and transitional epithelium to the vulvar vestibule between the hymenal membrane and the medial borders of the labia minora. Cancers arising in the Bartholin complex are conventionally categorized and treated as vulvar cancers.

FIGURE 52-3 • Surface anatomy of the vulva and vulvar lymphatic flow.

(From Russell AH: Vulvar and vaginal carcinoma. In Gunderson LL, Tepper JE, eds: Clinical radiation oncology, ed 2, Philadelphia, 2007, Elsevier/Churchill Livingstone, p 1388.)

The lymphatics of the vulva are constituted by a network that covers the entire labia minora, fourchette, prepuce, and distal vagina below the hymenal membrane. These coalesce anteriorly, forming larger trunks, which run lateral to the clitoris to the mons veneris, acquiring tributaries from the lymphatics of the labia majora, which run in a parallel fashion anteriorly from the perineal body (see Fig. 52-3). The vulvar lymphatics run through the vulva and do not cross the labiocrural fold. The lymphatics of the perineum, however, course lateral to the labiocrural fold through the superficial tissues of the upper medial thigh. In the treatment of patients with advanced vulvar cancer that extends beyond the vulva to the perineal skin or anus, these more lateral channels must be addressed. Similarly, extension of an advanced vulvovaginal cancer along the vaginal canal proximal to the hymenal ring implies attention to the potential direct pelvic lymphatic flow of the middle and upper vagina. At the mons veneris, the vulvar lymphatic trunks deviate laterally to the primary regional nodes, the ipsilateral or contralateral inguinal nodes. Study of the localization of radiolabeled tracer in regional lymph nodes after focal injection of discrete sites in the vulva and on the perineum reveals that the lymphatic drainage of the perineum, clitoris, and anterior labia minora is bilateral, whereas the lymph flow from well-lateralized sites in the vulva is, predominantly, to the ipsilateral groin. From the superficial inguinal nodes, secondary lymphatic drainage is through the cribriform fascia to the deep inguinal or femoral nodes, with subsequent tertiary flow under the inguinal ligaments to the deep pelvic (external iliac and obturator) nodes (see Fig 52-3). The node of Cloquet, also called Rosenmüller’s node, is the most cephalad of the femoral nodes, often lying in the femoral canal below Poupart’s (inguinal) ligament. Metastasis to Cloquet’s node is considered a herald of pelvic node contamination and a harbinger of distant dissemination.

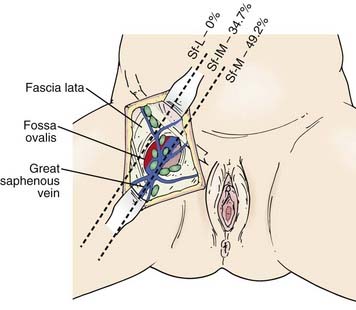

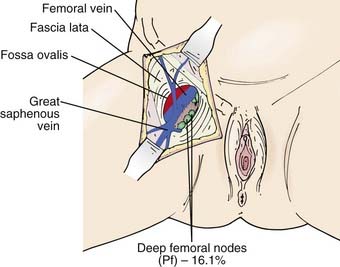

The subsurface anatomy of the groins as revealed by superficial and deep groin node dissections is depicted in Fig. 52-4. Sentinel lymph nodes have been extensively investigated in patients with vulvar cancer using blue dye technique and/or lymphoscintography. In a study of 59 patients with invasive vulvar cancers <4 cm in size who underwent anatomical localization of the sentinel nodes, 118 sentinel nodes were identified from 82 groins. Of these, 83.9% were in superficial groin nodes. Importantly, 16.1% were located in deep femoral nodes. No sentinel nodes were located in the outer third of the groin lateral to the femoral vessels (Figs. 52-5 and 52-6).74 These findings may be useful both with respect to planning the extent of groin surgery as well as the anatomic boundaries of radiation treatment volumes and prescription depth for elective groin irradiation.

FIGURE 52-5 • Location of sentinel nodes. Pf, Deep nodes—profundum.

(From Rob L, Robova H, Pluta M, et al: Further data on sentinel lymph node mapping in vulvar cancer by blue dye and radiocolloid Tc99, Int J Gynecol Oncol 17:147–153.)

Pathology

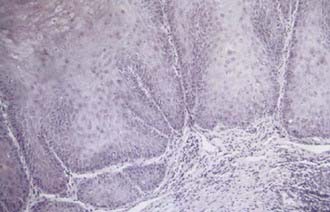

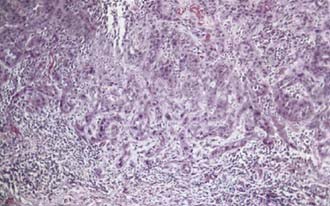

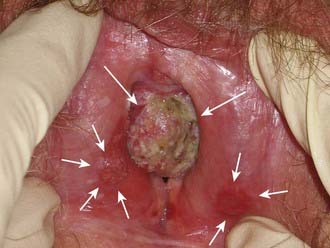

Malignant melanoma, adult and embryonal sarcomas of varied histologies, Merkel cell tumors, histiocytosis X, Kaposi’s sarcoma, hemangiopericytoma, lymphoma, eccrine carcinoma, primary breast cancers, basal cell carcinomas, adenocarcinomas, and adenoid cystic carcinomas (usually arising within the Bartholin glands), as well as other histologic tumor types have all been reported as primary malignancies arising from the vulva.75 However, more than 85% of invasive vulvar malignancies are epidermoid carcinomas76 leading to the common practice of using the terms squamous carcinoma of the vulva and vulvar carcinoma synonymously. Because of distinctive histopathology and characteristic clinical behaviors, it is important to recognize verrucous carcinoma (Fig. 52-7)77–82 and so-called “spray” pattern carcinomas (Fig. 52-8)83–85 as variants of squamous carcinoma with characteristic clinical behaviors. Verrucous cancer may resemble cauliflower in gross appearance, with a predominantly exophytic pattern of growth often accompanied by exuberant hyperkeratosis (Fig. 52-9). Histologically characterized by well-differentiated cells with a broad, pushing interface between cancer and surrounding stroma, verrucous cancer uncommonly metastasizes to regional lymph nodes, even when quite large, but often recurs locally after surgical therapy. Squamous cancers with finger-like microscopic projections, or a “spray” histologic appearance, often have a trabecular architecture of poorly differentiated cells with separate islands or discontiguous satellites of tumor cells in proximity to the infiltrative interface between the main tumor mass and surrounding stroma. These cancers may metastasize to regional nodes even when quite small and may recur at the skin margins of surgical resection, as well as relapsing distantly.

Paget’s disease of the vulva is a cutaneous change morphologically similar to Paget’s disease of the breast (nipple). Characterized histologically by large, vacuolated pathognomonic Paget’s cells with bluish cytoplasm located in the basal layer of the vulvar epithelium, Paget’s disease presents clinically as an eczematoid “weeping” lesion that is intensely pruritic. In many cases Paget’s disease may be treated with topical medications including steroids for months before a correct diagnosis confirmed by biopsy. Paget’s disease of the vulva is associated with an underlying in situ or invasive neoplasm in approximately 10% of cases. Neoplasms associated with Paget’s disease include adnexal apocrine skin carcinomas, carcinomas of Bartholin’s glands, and cancers of the urethra, bladder, vagina, cervix, endometrium, and rectum. Treatment is surgical, with cutaneous recurrences common. Negative surgical margins are difficult to obtain, because “Pagetoid” changes may extend microscopically in the epidermis, well beyond the margins of what can be appreciated on clinical examination. Negative surgical margins have only limited correlation with freedom from local relapse. Micrographic (Mohs) surgical technique has been advocated for Paget’s disease as a means to achieve negative margins with less extensive surgical extirpation. Rarely, Paget’s disease may become invasive, and metastases to groin nodes have been reported.86–94 Management including radiation has been reported with anecdotal favorable outcomes both in patients with invasive and noninvasive Paget’s disease.95–98 Radiation doses of 40 Gy to 56 Gy have been utilized in patients for whom the scope of surgery required to attempt surgical clearance would be medically unfeasible or functionally mutilating.

Clinical Presentation of Invasive Squamous Cancer of the Vulva

Pruritis or a localized sore are common presenting symptoms of vulvar cancer. Burning after urination may occur when urine comes in contact with areas of epithelial destruction and inflammation. Spotting and serous oozing may be noticed by the patient, but major hemorrhage is unusual. Most vulvar cancers arise in the labia, with only 15% involving the clitoris. The tumor is often exophytic, with a raised velvety red appearance, although centrally ulcerated lesions undermining surrounding skin may also be seen. Vulvar cancer may coexist with, and mimic, the gross appearance of venereal warts (condyloma acuminatum), which may result in neglect by the patient or delay in diagnosis (Fig. 52-10). Many vulvar cancers occur in older women who are not receiving regular gynecologic care or pelvic examinations. Because of inappropriate modesty, some patients will not report local symptoms to their physician. In circumstances where a tumor is not obvious, a patient may undergo unsuccessful treatment for a presumed dermatologic condition before a diagnostic biopsy. Because of patient and physician factors, delays in diagnosis of a year or longer after development of symptoms are not uncommon.

Routes of Spread

Vulvar cancer involves adjacent structures by direct extension. Invasion of the vagina is common (stage T3), often in conjunction with involvement of the distal urethra. When vaginal involvement is extensive, invasion of the bladder may be observed, or destruction of the rectovaginal septum with involvement of the rectal mucosa (stage T4). Extension to the perineum is frequent, often with involvement of anal or perianal skin. Extensive lesions may invade the anal sphincter. Satellite lesions in adjacent skin may occur, presumably by transit through dermal lymphatics. Squamous cancers of the vulva are autotransplantable, with “contact lesions” occupying mirror-image locations on the labia (Fig. 52-11). Rarely, extensive permeation of regional dermal lymphatics presents a picture analogous to peau d’orange of the skin of the breast (Fig. 52-12).

The earliest noncontiguous spread is to regional lymph nodes in the groin, which will be contaminated in approximately 30% of patients with operable vulvar cancer. Discrete (<2-cm diameter), well-lateralized primary cancers limited to the vulva and not approaching midline structures rarely spread to contralateral groin nodes in the absence of spread to ipsilateral nodes.23,24,99–104 Although direct lymphatic channels from the clitoris to the deep pelvic nodes have been described, these pathways are rarely of clinical significance.16,105 Direct lymphatic channels from the clitoris and anterior vulva to the femoral nodes exist, and probably account for occasional patients with metastatic spread to the deep femoral nodes without superficial inguinal node metastasis.74,83,101,106,107 Metastatic spread to pelvic nodes will be found in approximately 15% to 25% of patients with groin node metastasis, but only very rarely without previous gross involvement of the inguinal or femoral nodes and/or metastatic contamination of multiple groin nodes.6,7,17,18,108–115

Diagnostic Assessments

The joint 2010 staging system (Table 52-1) of the Fédération Internationale de Gynécologie et d’Obstétrique (FIGO), the American Joint Committee on Cancer (AJCC), and the Union Internationale Contre le Cancer (UICC) is a mixed clinical, surgical, and histopathologic staging system that relies on clinical examination and selected biopsies for the assignment of T stage and the results of biopsies or therapeutic node dissection for the assignment of N stage.

Table 52-1 AJCC 2010 Staging Classification of Cancer of the Vulva

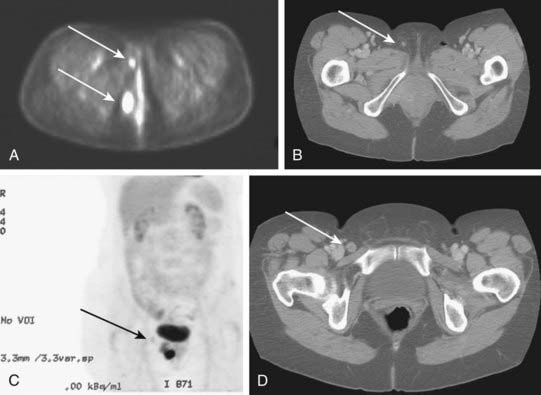

Potentially useful assessments to define extent of disease before therapeutic intervention include careful pelvic examination (possibly with anesthesia), chest radiography, computed tomography (CT), positron-emission tomography (PET), or PET/CT to assess regional nodes, and soft tissue optimized pulse sequence magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) to assess regional soft tissue extensions. For patients with very extensive lesions, cystourethroscopy and/or proctosigmoidoscopy may be indicated. For patients with clinically apparent groin node metastases, CT or PET/CT may be used to assess possible spread to pelvic or upper retroperitoneal lymph nodes. Histologic confirmation of groin node metastasis by fine-needle aspiration (FNA) cytology or imaging guided core biopsy is desirable before planning therapy as approximately 22% of clinically suspicious groin nodes will be benign and enlarged consequent to reactive or inflammatory changes (Fig. 52-13).2,7,18,109,111,116 A patient who will be treated with radiation must undergo a pelvic CT scan both to screen for gross adenopathy that may be too deep to palpate and to conduct accurate dosimetric planning of radiotherapy directed to the inguino-femoral nodes.

Identification of sentinel lymph nodes by lymphoscintography or isosulfan blue intradermal injection or both is an area of active clinical investigation.74,117–130 Lymphatic mapping may be helpful for selection of patients with lateralized primary cancers in whom treatment of the ipsilateral groin may suffice. Depending on surgical philosophy and the threshold for use of adjunctive therapies, confirmation of sentinel lymph node metastasis may alter the extent of surgical therapy both for patients with squamous cancers of the vulva and those with melanoma. However, treatment algorithms based on sentinel node identification and biopsy are not yet broadly accepted.

PET may be useful in evaluating patients with vulvar melanoma for distant metastases. A role for PET in squamous cancer has not been established. Preliminary evidence suggests relative insensitivity in detection of nodal metastases in the groins (67%), but a high specificity (95%).131 Thus, a negative groin PET alone should not exempt a patient from some form of therapy directed to the regional nodes. A positive study, particularly in a patient to be treated with definitive or preoperative radiation-based therapy, may assist in the selection of target volume and radiotherapy dose. Whenever possible, histologic confirmation of nodal status should be obtained by needle biopsy under ultrasound or CT guidance, or by excision. Fig. 52-14 illustrates the potential value of PET/CT in defining initial disease extent before treatment.

Standard Therapeutic Approaches

Surgery

For approximately 40 years, en bloc radical vulvectomy and bilateral regional lymphadenectomy (inguino-femoral with or without pelvic), using a single “butterfly” or trapezoidal incision, was the standard of care for patients with operable carcinoma of the vulva. The most common postoperative complication, frequently responsible for prolonged hospitalization and delayed recovery, is breakdown of the surgical wound in the groin. This complication is markedly reduced in frequency and severity by performance of the vulvectomy and the groin dissections through separate incisions, which serves to reduce tension on the skin flaps, preserve vascular supply, and improve the probability of primary healing.132,133 This refinement in technique, customarily reserved for patients with clinically uninvolved groins, comes at the price of the rare recurrence in the preserved bridge of tissue between the separate incisions. These failures may represent in-transit or retrograde lymphatic metastasis, unlikely events unless groin nodes are extensively contaminated.

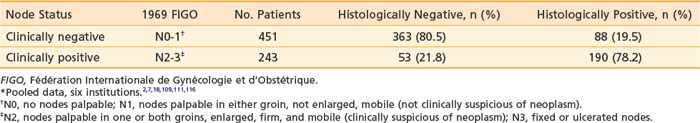

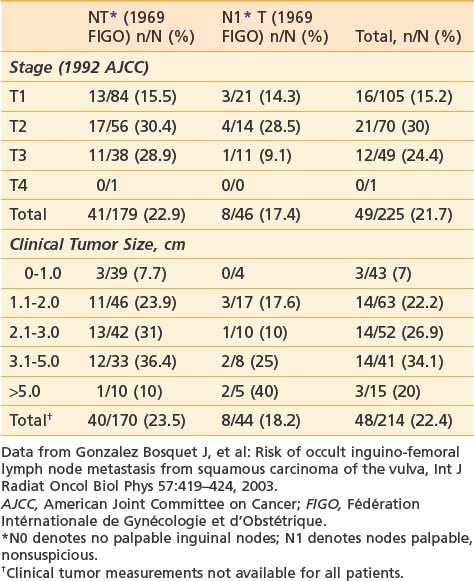

It is essential to appreciate that much of the classic surgical literature analyzes results using the 1969 staging system of FIGO, which employed clinical evaluation of both the primary tumor and the groin nodes. In 1989, FIGO adopted modifications to this staging system, resulting in a hybrid, clinicopathologic staging system that incorporated the results of histologic assessment of regional nodes, explicitly acknowledging the importance of nodal status in determining prognosis and therapy and implicitly recognizing the inaccuracies of clinical assessment of the regional lymph nodes by palpation. Approximately 20% of patients with clinically uninvolved groin nodes (1969 FIGO including N0 patients with nonpalpable groin nodes or N1 patients with groin nodes palpable, but not enlarged or suspicious) have histologic evidence of groin metastasis if subjected to radical groin dissection.* Approximately 22% of patients with clinically suspicious groin nodes (1969 FIGO including N2 patients with enlarged, firm, mobile nodes considered clinically suspicious, and N3 patients with fixed or ulcerated nodes) show no histologic evidence of nodal spread if the groin nodes are dissected (Table 52-2).*

The prognosis of surgically treated vulvar cancer is directly related to the presence or absence of regional node metastasis,134 the extent of lymph node infestation, and the anatomic level of nodal involvement. Five-year disease-free survival probability is approximately 95% for patients with T1-2N0 tumors7,135,136 decreasing to approximately 70% for stage T3N0.7 Disease-specific survival drops to approximately 64% at 5 years when groin nodes are involved at the time of initial treatment.134 Most recurrences are detected within 2 years of initial therapy. The probability of recurrence within 2 years is approximately 5% for surgically treated node negative patients, and approximately 30% for surgically treated patients with node metastases.134,136 Metastasis to a single node is prognostically less ominous than involvement of multiple nodes.16,17,137 Patients with unilateral node metastasis fare better than those with bilateral spread116 and 5-year disease-free survival drops to approximately 40% when multiple nodes are involved. Approximately 20% of patients with pelvic (iliac) node metastasis can be cured by locoregional therapies (surgery, radiation, or combined modality therapy).*

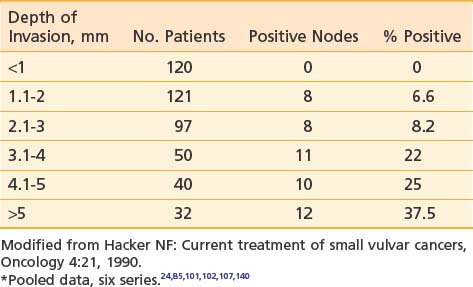

Tumor size, depth of invasion, presence of vascular or lymphatic space invasion, pattern of tumor growth and invasion, and histologic grade seem to be important predictors of lymph node spread as well as prognosis, although there is no consensus concerning the relative importance of each parameter in multivariate analysis.† Surgical specimens from patients with primary tumors 2 cm or less in diameter (T1) clearly show escalating risk of node metastasis with progressive depth of invasion (Table 52-3).‡ The risk of clinically occult involvement of inguino-femoral nodes in patients with palpably nonsuspicious groins undergoing complete groin dissection is tabulated by primary tumor size and T category in Table 52-4.141

Table 52-3 Incidence of Groin Node Metastasis Correlated With Depth of Invasion for Primary Tumors <2 cm*

Table 52-4 Probability of Clinically Occult Metastasis to Inguino-Femoral Lymph Nodes Correlated With Primary Tumor Category and Size

An infiltrative pattern of growth correlates with nodal spread, and the presence of vascular or lymphatic space invasion substantially escalates the probability of finding metastases in dissected nodes.104,115,142 The presence of metastatic spread to contralateral groin nodes in the absence of disease in ipsilateral nodes occurs in 15% or less of all patients with metastases to groin nodes,112 generally in patients with larger lesions. Although described in two patients with lateralized T1 lesions,50 the risk of contralateral nodal spread in the absence of ipsilateral metastasis is less than 3%.§ When metastatic disease is present in multiple groin nodes, pelvic lymphadenectomy will detect disease in 15% to 25% of patients.6,7,17,18,108–115 but rarely when only one groin node is microscopically contaminated.16,17 A thoughtful appraisal of the risk of nodal spread and the anatomical level of potential contamination is an essential part of determining target volume, dose, and technique for a course of radiation therapy, whether the radiation is given preoperatively, postoperatively, or as primary treatment.

Integration of radiation and surgery for optimal outcomes requires an understanding of the inherent strengths and limitations of primary surgical treatment and the extent of operative therapy to be performed. Surgical strategy is predicated on primary tumor parameters, clinical assessment of the groin nodes, the status of adjacent tissues, patient age and vigor, and patient preference. Based on an appreciation by the surgeon of clinicopathologic risk factors and an ability to identify patients who have minimal risk of nodal spread, radical wide local excision (employing a clinical margin of at least 1 cm in all dimensions) without node dissection has been reported to be a sensible surgical option for select patients with discrete tumors 2 cm or less in diameter, with 1 mm or less of invasion, and without an infiltrating or “spray” pattern of growth. Radical wide local incision implies a significantly deeper excision than is routinely employed for VIN. Radical excision extends to the level of the deep perineal fascia usually 1 to 2 cm below the skin. Provided the surgical margins are adequate, local recurrence will be observed in only 5% of such patients.22,24,101,103 Radical wide local excision may be appropriate for patients with larger or more deeply invasive primary tumors, but it should be accompanied by at least ipsilateral groin dissection. For patients with very well-lateralized T1 and T2 primary tumors confined to the labia, contralateral groin dissection may be omitted unless there is spread to the ipsilateral groin.22–24,99–104,143 Unless conservation of the clitoris and sexual function are of major importance to the patient, radical vulvectomy will generally be the most appropriate surgical management of the primary tumor for patients with multifocal invasive vulvar cancer, or patients with invasive cancer associated with extensive VIN or vulvar dystrophy that has been unresponsive to topical steroids.

The best clinical predictor of local recurrence is the adequacy of the surgical margin (Table 52-5).144–146 An 8-mm margin in fixed tissue, corresponding to a clinical margin of 1 to 1.5 cm, is a useful guide in planning conservative surgery for patients with primary tumors that approach or extend to critical normal structures such as the anus, urethra, distal vagina, and clitoris. The distal urethra (no more than 1.5 cm) can be removed with preservation of urinary continence in most patients147 although removal of only a portion of the anal sphincter may compromise fecal continence.148 The risks of both local recurrence and loss of normal tissue function must be judiciously assessed and compared with risks associated with alternative strategies, such as those employing preoperative radiation or chemoradiation with less extensive surgery or chemoradiation alone. Exenterative surgery, even for massive primary disease, should seldom be chosen as initial therapy unless the cancer has already destroyed the functions of the critical normal tissues that might otherwise be preserved. It is rarely appropriate when regional node metastases are present.8

Table 52-5 Width of Surgical Margin and Risk of Local Recurrence

| Series | Margin <8 mm, n/N (%) | Margin ≥8 mm, n/N |

|---|---|---|

| Heaps146 | 21/44 (48%) | 0/91 |

| Chan145 | 12/53 (23%) | 0/30 |

| De Hullu144* | 9/40 (23%) | 0/39 |

* Surgical margin of <8 mm versus >8 mm.

The extent of groin dissection in the setting of confirmed metastasis to one or more groin nodes remains controversial. Outcomes analysis comparing nonrandomized patients undergoing complete groin dissection followed by radiation versus resection of enlarged/suspicious nodes only followed by radiation suggest that the limited surgical approach is associated with equivalent control in the groin (groin relapse-free survival) and no change in overall survival. Theoretically, both acute and late morbidities could be expected to be less among patients undergoing less extensive groin dissection before radiation, but complications and quality of life could not feasibly be assessed in this multi-institutional study.149

Chronic leg lymphedema may develop in 30% or more of patients undergoing radical dissection of superficial and deep inguino-femoral nodes. In an effort to reduce this risk, the concept of sentinel node dissection has been extended to the management of vulvar cancer during the past decade.74,117–130 Among patients at risk for groin node metastases, negative sentinel nodes may identify those least likely to benefit from radical dissection of groin nodes. Gynecologic Oncology Group protocol 173 is an active trial of sentinel node mapping in patients with vulvar cancer. In this study, sentinel nodes are identified by blue dye and/or lymphoscintography. Subsequent to surgical excision of the sentinel nodes, a comprehensive groin dissection is performed. The principle endpoints of the study are to quantify the negative predictive value of a sentinel node biopsy and to describe the anatomical location of sentinel nodes. This protocol is intended to accrue a total of 630 patients.

A multi-institutional study from The Netherlands reported preliminary outcomes for 403 patients with T1/T2 cancers of the vulva undergoing sentinel node procedures studying a total of 623 groins. When the sentinel nodes were found to be histopathologically negative, inguino-femoral lymphadenectomy was omitted. With a median follow-up of 35 months, 6 groin recurrences (2.3%) were diagnosed among 259 patients with a negative sentinel node and unifocal vulvar disease, and 3-year survival was estimated to be 97%. Chronic complications were markedly reduced in patients undergoing groin surgery limited to the sentinel nodes compared to patients undergoing sentinel node removal followed by inguino-femoral lymphadenectomy. Recurrent episodes of erysipelas were seen in 0.4% of the former compared to 16.2% of the latter. Leg lymphedema was reduced from 25.2% in patients undergoing complete groin dissection to 1.9% in patients undergoing only sentinel node removal.117 This study would suggest that the negative predictive value of a sentinel node study is high. However, as the consequence of groin relapse is usually a fatal outcome in patients with vulvar cancer,110,150–155 it will be critical to know the false negative percentage with the greatest possible precision before abandoning traditional surgical therapy associated with an excellent probability of regional cancer control.

Approximately 80% of patients in whom surgical therapy fails suffer recurrences in the residual vulva, on the perineum, at the vaginal introital margin, in the groins or upper thighs, or in the pelvis, and less than 20% have recurrences distantly.24,25,150–152,156–158 Parameters that are predictive of locoregional recurrence include the width of the surgical margin, the presence of groin node metastasis, vascular or lymphatic space invasion, and an infiltrative pattern of growth. The presence of one or more of these factors should prompt consideration of adjuvant radiation.

Radiation Therapy

Radiotherapy is increasingly employed in the curative management of vulvar cancer, often in conjunction with synchronous administration of radiation potentiating chemotherapy. Radiation salvages some patients with locoregional recurrence after radical vulvectomy and regional node dissection.155 Postoperative radiation directed to the groins and pelvic nodes improves disease-free survival in patients with metastatic spread to two or more inguino-femoral nodes25,156 and may further improve results if residual vulva and perineum are included within the irradiated volume.159 Preoperative radiation or chemoradiation have reduced the indications for exenterative surgery and may permit a substantial decrease in the volume of normal tissue that must be removed in patients with tumors invading or intimately approximating functionally important midline structures (anus, clitoris, urethra, and vagina).* Radical chemoradiation provides sensible alternative therapy for patients who are technically unresectable or medically inoperable.36,40–43

Salvage Radiation Therapy

Postsurgical, central, limited-volume, local recurrence in the residual vulva—at the introital margin or on the perineum—will often be salvaged with secondary surgery, radiation, or combined-modality therapy.20,151,152,155,170 A disease-free interval of 2 or more years and lack of involvement of regional nodes portend a more favorable outcome with salvage therapy.152 Under circumstances in which the anticipated surgical margin is less than that of the original surgery, when recurrence approaches or involves critical structures, or when the pattern of recurrence is multifocal, it is prudent to plan for delivery of radiation as at least a component of the salvage strategy. Regional relapse in the groin or in pelvic nodes is much less likely to be salvaged, regardless of the combination of modalities used.* Radiation alone, in doses ranging from 63 Gy to 72 Gy employing progressive volume reductions or partial treatment with brachytherapy, often controls small-volume recurrence. Preoperative radiation ranging in dose from 45 Gy to 54 Gy followed by local excision may be less injurious in terms of delayed normal tissue effects than a high radiation dose to a large perineal volume in the absence of surgery. The majority of patients with vulvar cancer who develop clinical recurrence do so within 2 years of initial therapy,134,152 and recurrent disease may grow rapidly. Thus, when a combined approach employing surgery and radiation is planned, it is best to commence with radiation, as residual occult cancer may proliferate more rapidly than the wound heals. Chemoradiation, either as preoperative or definitive salvage therapy, may offer equivalent or better prospects for local-regional control than higher doses of radiation alone with lesser late effects in normal tissues. However, the role for chemotherapy concurrent with radiation has not been firmly established in the context of salvage treatment after surgery.

Adjuvant Postoperative Radiotherapy

The Gynecologic Oncology Group conducted a randomized prospective trial (GOG protocol 37) comparing pelvic lymphadenectomy with radiotherapy directed to the bilateral groins and pelvic nodes (but not the tumor bed or perineum) in patients who were found to have groin node metastasis.25,156 The results of this trial confirm statistically improved cancer specific survival and overall survival for irradiated patients at 6 years. A total of 111 eligible patients were randomized, 39 of whom had only one positive groin node. In 13 patients of 54 undergoing pelvic lymphadenectomy, disease had spread to pelvic nodes (24.1%). In the pelvic node resection group, 8 of 17 (47%) patients had pelvic node metastases when ≥20% positive ipsilateral groin nodes were observed. Five of 37 (14%) patients had pelvic node metastases when less than 20% positive ipsilateral groin nodes were retrieved. None of the 18 patients with clinically nonsuspicious groin nodes (AJCC 1969 N0/N1) who had occult groin node metastases had spread to resected pelvic nodes. After long-term follow-up, those patients with AJCC 1969 N2/N3 groin nodes or two or more positive nodes significantly benefited from radiation treatment. At 6 years, 87 percent of those patients undergoing radiation for a single groin lymph node metastasis (n = 18) and 81 percent of those undergoing pelvic node resection (n = 21) were predicted to be alive and disease free. A ratio of more than 20% positive ipsilateral groin nodes (number of ipsilateral positive groin nodes/number ipsilateral groin nodes retrieved) was associated with contralateral node metastasis, pelvic node metastasis, and statistically significantly increased risk of recurrence and cancer-related death. At 6 years, 48% of patients treated by radiation were predicted to be alive and disease-free compared to 19 percent of those treated by pelvic node resection. Estimated cancer-related and overall survival in patients treated by radiation were 56% and 36%, respectively, compared to 13% each in patients treated by pelvic node resection. No central vulvar radiation was administered in GOG protocol 37. A total of 13 of 111 patients (12%) had local vulvar cancer recurrences. Thirteen groin recurrences were recorded in the 54 patients in the pelvic node resection group (13 of 27 recurrences, 48%) compared to three groin recurrences among the 54 patients in the irradiated group (three of 21 recurrences, 14%). Chronic lymphedema was reported in 16% of irradiated patients compared to 22% of patients treated with pelvic node dissection. As a consequence of this study and confirmatory data from others,171 pelvic lymphadenectomy is less likely to be performed and regional adjuvant radiation has become the standard of additional care for patients with metastasis to two or more regional nodes or gross nodal metastasis. Whether adjuvant radiation might benefit patients with metastasis to only one groin node remains controversial, with population-based outcomes data providing some justification for this approach.172 When nodal involvement is more than microscopic or extracapsular invasion into perinodal adipose tissue is documented, adjuvant radiation is reasonable.

Because many patients in whom disease spread to regional nodes also have adverse prognostic factors predictive of local relapse, it is sensible to consider inclusion of the primary tumor bed and perineum in the treatment volume when postoperative radiation is administered because of lymph node metastases. A high risk of tumor bed recurrence has been reported in the context of adjuvant nodal irradiation when a midline block has been used to shield residual vulva and midline structures (vagina, urethra, anorectum).159

Some resected patients with negative groin nodes will be at risk for local recurrence at the margins of resection laterally or deep to the primary tumor. Less than 8-mm surgical margin should prompt consideration of adjuvant radiation to the tumor bed and adjacent perineum, which is often feasible with an en-face perineal port employing low energy photons or electrons. Such treatment substantially reduces the risk of local recurrence and may favorably impact on survival in patients with positive margins.173

Preoperative Radiation and Chemoradiation

Under circumstances in which the extent of the primary disease indicates postoperative radiation, it is reasonable to consider preoperative radiation, particularly if it has the potential to reduce the scope of surgery and to conserve normal tissue structure and function or to convert the status of the patient from unresectable to operable.* An anticipated clinical margin of 1 cm or less from structures that will not be removed surgically is a useful guide for selecting patients for preoperative radiation. Tumors that encroach on the anal sphincter, abut the pubic arch, or involve more than the distal urethra should be considered for preoperative therapy. Patients with tumors that approach the clitoris or extend more than minimally past the vaginal introitus should also be considered for preoperative irradiation if conservation of sexual function is an important treatment goal. Moderate-dose radiation alone (36 Gy to 54 Gy) has been given, followed by excision of residual palpable abnormalities that revealed no evidence of persistent cancer in approximately 50% of cases.27–29 External beam radiation therapy is most commonly employed, but interstitial or intracavitary brachytherapy may apply a higher dose to a discrete tissue volume where a surgical margin is anticipated to be inadequate.26

Gynecologic Oncology Group protocol 101 studied 73 patients with stage III to IV squamous cancers of the vulva who were judged not amenable to resection due to local disease extent beyond the conventional boundaries of radical vulvectomy. Preoperative chemoradiation, consisting of 47.6 Gy delivered in fractions of 1.7 Gy, coordinated with two cycles of synchronous cisplatin and 5-FU, converted 69 of 71 patients medically fit for surgery to having lesions considered amenable to resection. Ultimately, urinary and fecal continence was conserved in all but three patients. With the use of this approach, local tumor control has been excellent, with conservation of normal tissue integrity in many patients who would otherwise have required exenterative surgery for tumor clearance.39 Employing the identical regimen in 46 patients with extensive (matted, fixed, or ulcerated) and unresectable groin metastases, clinicians of the Gynecologic Oncology Group were ultimately able to resect groin nodes in 37 patients,15 of whom had histologically negative groin specimens.174 Slight modifications in the time-dose-fractionation schedule of GOG protocol 101 led to the regimen currently employed at Massachusetts General Hospital (Table 52-6) which completes 47.6 Gy preoperative chemoradiation in 33 days/5 weeks with a 3-week interval between the two cycles of chemotherapy administered synchronously with radiation during the first and fifth week. The severity of the acute moist desquamation of the vulva and adjacent perineum may mimic the appearance of a second-degree thermal burn. Accelerated repopulation of normal skin results in rapid re-epithelialization during 10 to 14 days (Figs. 52-15 and 52-16). The volume of irradiated skin can be reduced by treating patients in a frog-leg position to avoid unnecessary irradiation of the upper medial thigh, except when the primary tumor has extended across the labiocrural fold onto perineal skin. Meticulous skin care and comfort measures are required to usher patients through the painful period of moist desquamation as comfortably as possible. Frequently, the additional patient and clinician effort necessitated by combined-modality therapy is rewarded by dramatic, rapid tumor regression (Figs. 52-17, 52-18, and 52-19). Three weeks after the completion of the second cycle of chemotherapy is generally required for complete skin healing. For patients judged unsuitable for conservative surgery 2 to 3 weeks following preoperative chemoradiation, a third cycle of chemoradiation is administered generally during the ninth week of treatment to bring the cumulative dose to 61.2 Gy to 64.6 Gy, often employing a perineal, en face port (Fig. 52-20). Brachytherapy (interstitial or intravaginal) may be a useful alternative to treat a small reduced volume to higher cumulative radiation dose without additional chemotherapy.

Table 52-6 Chemoradiation Regimen Employed at Massachusetts General Hospital (Gynecologic Oncology Group Protocol 101)

Seeking to reduce both acute skin and hematologic toxicity, the Gynecologic Oncology Group is currently investigating weekly cisplatin at a dose of 40 mg/m2 coordinated with radiation (GOG protocol 205) as an alternative preoperative regimen for patients similar to those entered into GOG protocol 101. Patients receive 57.6 Gy in 32 fractions of 1.8 Gy administered once daily, as opposed to the 47.6 Gy in fractions of 1.7 Gy employed in GOG protocol 101. Limited data regarding response rates to preoperative neoadjuvant chemotherapy alone show that the combination of 5-FU and cisplatin has substantially greater primary cytotoxicity than cisplatin alone, suggesting that the higher physical radiation dose employed in GOG protocol 205 may be both prudent and necessary.175

Radical Radiotherapy and Chemoradiation

The observation of complete histologic clearance of malignancy following moderate-dose preoperative radiation (alone or coordinated with synchronous chemotherapy) serves to encourage efforts to control vulvar cancer with radiation-based therapy under circumstances in which surgery is either technically unfeasible or medically contraindicated. Historically, results with radiation alone have been poor in terms of both tumor control and normal tissue sequelae. However, the tumor control probability for patients with disease of limited volume has approached that of surgery.11,30,176 The favorable experience with chemotherapy and reduced-dose radiation in the treatment of cancers of the anal canal has prompted increasing use of this approach in the treatment of advanced vulvar cancer. Most published experiences employed 5-FU, with or without cisplatin or mitomycin. Small numbers of reported patients with heterogeneous disease undergoing individualized and quite variable management with chemoradiation, coupled with the small number of such patients available for long-term surveillance, necessarily render any conclusions preliminary. Often such patients represent individuals with regionally advanced disease undergoing chemoradiation with preoperative intent whose response is inadequate to permit completion of treatment by conservative surgery.

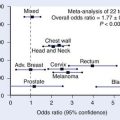

Retrospective study of treatment outcomes comparing chemoradiation with radiation alone suggests improved cancer control with chemoradiation,167 but prospective randomized data do not exist to validate the clinical impression of better results. Unquestionably, the administration of concurrent chemotherapy augments the acute reaction in normal tissues. Moist desquamation of the vulva necessitates treatment interruption in most patients. Hybrid dose/fractionation regimens have been developed to preserve dose intensity and to maximize potential synergistic effects. Twice-daily fractionation has become a popular strategy to exploit the radiation-drug interaction while minimizing the theoretic disadvantages of split-course radiation that is made mandatory by the enhanced effects in normal tissue.40,42,43 Fraction size should not exceed 1.8 Gy, and a fraction size as low as 1.6 Gy has been recommended to reduce late sequelae.177 Reduction of treatment volume after completion of dose directed to potential occult sites of subclinical metastasis is essential. The reduced volume receiving full dose should be as small as possible, while reproducibly including all areas of residual clinical involvement. The volume for “boost” treatment should approximate the volume which would be resected were conservative surgery to be employed to complete therapy. Brachytherapy may be a feasible alternative to teletherapy in selected patients, particularly when there is significant extension up the vagina (see Fig. 52-19). When treating a reduced volume with teletherapy, an en-face perineal port employing electrons will minimize exposure of adjacent tissues (see Fig. 52-20). Accurate setup of a perineal port may require physician verification with each treatment to assure appropriate coverage while minimizing the width of margins. Response rates for initial chemoradiation for locally advanced vulvar cancer are presented in Table 52-7.

Elective Groin Radiation

A contributing factor to perioperative complications and chronic morbidity is the dissection of the inguino-femoral nodes. Postoperative wound breakdown is frequent, and chronic lymphedema is a common consequence of radical surgical treatment of the groins.178 In select patients with limited primary tumors (<2 cm diameter and <1 mm of invasion), omission of the node dissection is prudent. Dissection of the groin nodes through a separate incision from that used to remove the vulvar primary tumor substantially reduces the probability of wound dehiscence. Elective irradiation of clinically negative groins is an alternative strategy that has the theoretical advantage of treating all of the regional nodes rather than leaving all, or some portion, untreated. This approach may also be applicable to patients with locally advanced primary tumors, in whom less than radical bilateral groin dissection would be inadequate surgical therapy. Several series have reported favorable results with elective or prophylactic groin irradiation (Table 52-8) but frequently in the setting in which groin nodes would be expected to be histologically uninvolved if treated surgically (e.g., T1-2 primary tumors of limited extent; see Table 52-4).141,179

Table 52-8 Results of Elective Groin Radiation or Chemoradiation in Patients With Vulvar Cancer and Clinically Negative Inguino-Femoral Lymph Nodes*

The Gynecologic Oncology Group, in a randomized trial, compared groin irradiation with groin surgery in select patients with vulvar cancer.180 The study was terminated early because of an unacceptable rate of groin node failures (5/27 patients, 18.5%) observed in the group assigned to radiation. Technical inadequacies in radiation administration may have inadvertently caused substantial underdosage of inguino-femoral nodes, resulting in the observed failures.181 In that study, the prescription depth of the groin nodes was arbitrarily specified at 3 cm below the anterior skin. A portion of the radiation dose administered to the groins was delivered using 12 MeV or 13 MeV electrons, resulting in potential underdosage of nodes which may lie deeper. As seen in Fig. 52-21, deep femoral nodes with metastatic cancer may lie 8 cm or more below the skin surface. Conversely, superficial inguinal nodes containing metastatic deposits may lie as little as 5 mm below the skin surface, within the build-up region of high energy photon beams, as seen in Fig. 52-22. Conventionally, dose to groin nodes is usually prescribed to the depth of the femoral artery as it passes below the inguinal ligament to assure adequate dose delivery to the deep femoral nodes which may contain sentinel nodes in 16% of cases.74

Chemoradiation162,182 may be a mechanism to improve the results of elective groin irradiation (Table 52-9). At the Radiation Oncology Center in Sacramento, 23 previously untreated patients with locally advanced primary squamous cancers of the vulva (stages T2 [n = 2], T3 [n = 20], and T4 [n = 1]) and clinically negative groin nodes have electively undergone chemoradiation to a volume that included the inguino-femoral nodes, without subsequent surgical therapy to the groins. No patient has suffered relapse in an irradiated groin.182 Among 17 similar patients (stages T2 [n = 4] and T3 [n = 13]) under going elective groin chemoradiation at Loma Linda University Medical Center, no patient experienced groin relapse.162 Elective groin irradiation is likely to remain a controversial issue in the therapy of patients with limited-volume operable primary tumors and clinically negative nodes in whom radiation may be avoided if histopathologic results of radical surgery are favorable. Negative sentinel node biopsies may obviate the need for groin treatment for many patients, although a small risk of subsequent groin failure persists despite negative sentinel nodes.117 However, for patients who are already undergoing preoperative or definitive radiation or chemoradiation because of the extent of the primary tumor, extension of the treatment volume to encompass the regional nodes may be a sensible alternative to groin dissection. Elective nodal irradiation to a volume encompassing the groins and the low pelvic nodes may be associated with less acute and chronic morbidity than bilateral groin dissection, particularly if postoperative groin and pelvic node irradiation is administered because the groin nodes are found to be microscopically involved.

Techniques of Radiotherapy

There is no standard approach to the treatment of vulvar cancer with radiation. The circumstance of radiation (postoperative, preoperative, or as definitive treatment) will influence the designation of target volume, fractionation, and dose. Clinical and histopathologic characteristics of the primary and regional nodes may independently affect the selection of treatment parameters, which also depend on the scope of any coordinated surgery and whether chemotherapy is to be administered with radiation. Selection of an appropriate target volume necessitates appraisal of the patient’s general condition and the presence or absence of comorbidities that may compromise the optimal use of radiation. The health of all of the normal tissues (small and large bowel, blood vessels, nerves, bones, bladder, vulvar and perineal skin) that might be included in the treatment volume should be assessed; such an assessment may indicate alterations in treatment volume and technique. Comorbidities in elderly patients may constrain the volume and intensity of treatment. Conservation of ovarian function and possible reproductive integrity in younger patients may also influence the technique of treatment.183

Volume for Postoperative Radiation

The target volume in patients undergoing treatment for groin node involvement detected at the time of radical vulvectomy should, in general, include both groin areas and the caudal pelvic nodes on the affected side. If there has been no surgical assessment of the pelvic nodes, a CT scan or equivalent imaging modality should be used to define whether pelvic nodes are grossly enlarged, and a FNA biopsy should be performed if suspicious nodes are detected. In the absence of clinical pelvic node involvement, the superior border of the treatment volume should encompass the caudal external iliac nodes and will not usually extend higher than the middle of the sacroiliac joints. When node involvement cephalad to the inguinal ligament has been documented at surgery or by postoperative imaging, the superior border of the treatment volume may be extended to the level of the L3-L4 interspace to encompass the common iliac nodes. The extent of the nodal treatment volume need not be symmetric in patients with only unilateral groin or pelvic node metastasis.184 In general, the principle of extending node treatment volume one nodal echelon proximal to the level of clinical involvement is a prudent guideline, absent major medical contraindications. The lateral border of the treatment volume should encompass the full extent of the operative dissection. If there has been invasion of overlying skin, inclusion of an additional 5 cm of the skin flaps is prudent to encompass potential contamination of dermal lymphatics. If there has been extensive nodal involvement (more than microscopic, subcapsular embolization of the medial inguinal nodes), the caudal border of the treatment volume should encompass the inferior inguinal node chain lying along the saphenous vein in the upper medial thigh. Accumulating evidence suggests that under circumstances dictating irradiation of the groin and pelvic nodes, it is usually wise to include the vulvar tumor bed and adjacent perineal skin, because of the substantial risk of recurrence in this volume when midline shielding has been employed.25,156,159 When an infiltrating, or “spray,” pattern of tumor growth is detected in the primary site, wider margins of clinically normal tissue should be included around the tumor bed and perineum. If the primary tumor has grown across the labiocrural fold, treatment volume should include the lymphatics that run through the upper medial thighs on the affected side. Occasional patients with negative, fully dissected groin nodes have indications for local tumor bed irradiation only. Gratuitous extension of the treatment volume to encompass the groins or pelvic nodes only increases the risk of subsequent lymphedema, femoral neck fracture, or other late sequelae, and should be avoided.

Volume for Preoperative Radiation

Use of radiation before surgery should be considered either when surgical margins are anticipated to be inadequate (1 cm or less of clinically normal tissue) or when the scope of initial surgery would compromise the functional integrity of important normal tissues (anus, urethra, clitoris, bladder). Usually patients with these conditions have T3 or T4 primary tumors, but occasionally patients, particularly thin individuals, have predictably inadequate margins with T2 primary tumors. Fixed or matted groin nodes or nodes invading or ulcerating through overlying skin are additional indications for preoperative radiation. If preoperative radiation is to be used, the histopathologic status of suspicious groin and pelvic nodes should be assessed before treatment by FNA or by excisional biopsy. CT or PET/CT through the pelvis and inguinal areas should be used both diagnostically and for treatment planning, with FNA assessment of abnormal findings. At Massachusetts General Hospital in Boston, it has become standard practice to include groin and caudal external iliac nodes in the initial target volume for most patients undergoing preoperative chemoradiation, even if these structures are clinically and radiographically uninvolved. Generally, the extent of the primary lesion suggests a substantial possibility of occult nodal contamination.141 Moderate dose radiation (40.8 Gy to 47.6 Gy) is applied synchronously with chemotherapy, with the intention of sterilizing potential occult nodal micrometastases. Illustration of target volumes is seen in Fig. 52-23. Clinically negative groins are not dissected when the primary tumor is removed. Critical to the success of elective groin irradiation is delivery of dose to appropriate depth in tissue. Conventionally, the depth of the deep femoral nodes is defined as the depth of the femoral artery as it passes beneath the inguinal ligament. This will be most accurately measured by CT. If groin nodes are histologically confirmed to be grossly involved, preoperative chemoradiation is administered and limited dissection of residual palpable nodes is carried out at the same time as removal of the primary tumor. The anatomic extent of the target volume is determined in a fashion similar to that used to define the target volume for postoperative radiation, with the exception that a larger pelvic node volume may be treated if the primary tumor extends to involve the middle or upper vagina, proximal urethra, bladder, or rectum, or if groin nodes are extensively involved. Because of potential lymphatic dissemination to hypogastric, perirectal, or mesorectal nodes under such circumstances, full pelvic radiation may be indicated in selected patients with locally extensive primary tumors.

FIGURE 52-23 • A slender patient, aged 46 years, with T3N1 squamous carcinoma of the right vulva with right groin metastasis (see Figure 52-22) proven by biopsy with the primary tumor adjacent to the clitoris and invading the distal 5 mm of the urethra. Preoperative chemoradiation was CT-planned and administered to encompass the vulva and caudal vagina, the full right groin, and the right caudal external iliac and obturator nodes. The clinically uninvolved left groin nodes were treated medial to the femoral artery. A, Initial volume treated with parallel opposed fields. External iliac arteries and femoral arteries are in purple and red. Outline of field edges (white line) indicated by small white arrows. The full right inguino-femoral chain of nodes, contoured in yellow, is indicated by large yellow arrows. B, Reduced volume treated for four fractions of 1.7 Gy. Red arrows indicate field reduction to exclude the right pelvic nodes (radiographically uninvolved) to decrease dose to terminal ileum. C, Coronal isodose distribution for initial volume. The prescription dose to the vulva and groin nodes was 47.6 Gy in 28 fractions during 33 days, with 34 Gy administered at 1.7 Gy twice-daily, concurrent with two cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin. The electively-treated right external iliac nodes received 40.8 Gy in 24 fractions during 33 days, with 34 Gy administered at 1.7 Gy twice-daily, concurrent with two cycles of 5-FU and cisplatin. Completion conservative surgery was limited to the vulvar primary and initially grossly involved right groin node.

Technique

Reasonable techniques include the use of a large anterior photon field designed to encompass the entire target volume, a smaller posterior photon field designed to encompass the perineum, pelvic nodes, and medial inguino-femoral nodes while excluding the femurs, and use of supplemental anterior electron fields to bring up the dose to inguino-femoral node areas that overlie the femoral heads and necks.42 Another technique employs a large anterior photon field used to encompass the entire target volume and to deliver the full dose to the groin areas, utilizing a partial transmission block centrally to attenuate dose to the midplane of the low pelvis (central axis) to 50% of the daily dose, the remaining 50% being administered through a smaller posterior pelvic photon port, which excludes the femoral necks.185 When available, use of different (lower) photon energies further reduces dose to the femurs (Fig. 52-24). Depending on treatment technique, the potential for “hot” areas exists at the abutment of the inguino-femoral node treatment volumes and the primary tumor treatment volume. The potential hazard of these focal areas of dose inhomogeneity may be mitigated through the use of moving junctions or “feathering” the field abutments. The modified segmental boost technique,186 employing fixed photon beams is a technique which minimizes potential “hot spots” at the points where adjacent ports abut on, and immediately below, skin overlying the groins (Figs. 52-25 and 52-26).

Recent reports describe favorable preliminary results using intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) in the treatment of locally advanced vulvar cancer (Fig. 52-27).168,187 Improved conformality with reduced dose to organs/structures at risk for late radiation sequelae comes at the price of somewhat increased dose heterogeneity within target volumes. However, this technique may also reduce the intensity of potential focal “hot” areas at the abutment of volumes targeting the groin nodes and the primary tumor. The heterogeneity of patients with vulvar cancer precludes a facile class solution for treatment with intensity modulated radiation therapy technique. The requirement to deliver therapeutic dose to the skin implies additional complexity in treatment planning with software algorithms that are imprecise for calculation of dose in the buildup region. Designation of the at-risk skin as a clinical target volume or gross tumor volume target can be very helpful. In addition to the ordinary IMRT requirements for meticulous patient positioning and immobilization, reproducible application of custom-designed bolus material may be required for accurate dose delivery. At this time, whether IMRT will result in better long-term normal tissue tolerance with improved functional and cosmetic results, remains speculative.

Treatment to a reduced volume limited to gross primary disease can be accomplished by small opposed anterior and posterior photon fields, but usually excludes more normal tissue if accomplished with an en face perineal electron or orthovoltage port (see Fig. 52-20). Under some circumstances, such as significant vaginal mucosal extension, interstitial or intracavitary brachytherapy may be useful to carry a discrete tumor volume to high dose (see Fig. 52-19).

Fractionation and Dose

Definitive radiation-based therapy for vulvar cancer is difficult to do because of the requirement to administer a high dose to what is fundamentally a skin tumor, involving tissue that is frequently moist from perspiration and lack of ventilation and that is subject to continual friction through walking and other normal activities. Acute radiation dermatitis is worse in the vulva, perineum, and groins, with moist desquamation and pain the predictable consequence of a continuous course of conventionally fractionated radiation. Interruption of therapy, either mandated by skin reaction or planned to avoid severe acute effects, is the rule and may prolong the elapsed time required to complete a course of radiation by 2 or more weeks, prompting consideration of compensatory increase in the total dose. Topical application of granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor impregnated gauze has been reported to decrease the severity and duration of acute radiation dermatitis and may reduce the duration of treatment interruption.188

Acute skin reactions and the need for treatment interruption have led to the use of hybrid fractionation regimens employing twice-daily fractionation for all or a portion of the treatment, as well as planned treatment interruptions both for skin and hematological recovery.* Multiple daily fractions during chemotherapy infusion will, theoretically, maximize radiation-drug synergism.

The chemotherapy agent most commonly used has been 5-FU, in doses from 750 mg/m2 per 24 hours to 1000 mg/m2 per 24 hours for 72 to 120 continuous hours. Cisplatin at 40 to 70 mg/m2 to 100 mg/m2 has been used as a second agent (renal function permitting), as well as mitomycin C at 6 mg to 12.5 mg/m2. The preoperative fractionation scheme employed by the Gynecologic Oncology Group in protocol 101 is a rational approach to preserving dose intensity, maximizing radiation-drug synergy, minimizing treatment interruption, and minimizing late effects in normal tissue through the use of reduced dose-per-fraction, twice-daily radiation.39 Minor modification of this schedule, as currently employed at Massachusetts General Hospital (see Table 52-6) reliably permits completion of treatment to an initial large volume targeting potential clinically occult sites of micrometastases in 5 weeks along with two cycles of chemotherapy. Following a treatment interruption of 3 weeks to allow healing of the inevitable confluent moist desquamation, the patient is jointly reevaluated by the gynecologic oncologist and the radiation oncologist for potential conservative local excision. Should that not be feasible, a third cycle of chemoradiation is usually administered to a reduced volume encompassing residual gross disease with a minimal margin. Alternatively, brachytherapy is occasionally used without chemotherapy to treat residual volume unresectable by conservative surgery. Guidelines for radiation teletherapy dose, alone or in combination with concurrent chemotherapy, are summarized in Table 52-9 and are compartmentalized for volume of disease (microscopic versus gross) and treatment intent (preoperative, adjuvant postoperative, or radical).

Critical Normal Tissues

Chronic skin sequelae are minimal and usually asymptomatic in patients receiving moderate-dose adjuvant preoperative or postoperative chemoradiation coordinated with surgery (Fig. 52-28). Some degree of chronic skin injury is inevitable in patients undergoing radical radiotherapy to high dose, and skin changes are progressive for 5 or more years after completion of therapy. Skin and subcutaneous sequelae can be minimized by the use of lower dose per treatment fraction and judicious restriction of the volume to be carried to high dose for gross disease. Dose to clinically uninvolved skin rarely needs to exceed 45 to 47.6 Gy in 25 to 28 fractions, with or without concurrent chemotherapy. Special care should be taken to exclude perianal, anal, and clitoral skin from high-dose volumes to minimize the hazard of late functional sequelae. Dose to the small intestine should not exceed 50.4 Gy in 28 fractions, even if only small volumes are to be treated.

FIGURE 52-28 • Photographs of a patient 10 years after conservative surgery (local excision with limited debulking ipsilateral inguino-femoral lymphadenectomy) for T2N1 squamous carcinoma of the left Bartholin gland. Postoperative chemoradiation was administered to a volume similar to that in the patient in Figure 52-23, encompassing the medial contralateral groin nodes, the vulva, the ipsilateral groin, and undissected low pelvic nodes on the left. 45 Gy in 25 fractions during 5 weeks was given with two cycles of concurrent infusional 5-FU and cisplatin. Before treatment the patient was sexually active, orgasmic, continent of stool and urine, and without leg edema. Ten years after treatment these clinical parameters are substantially unchanged. A, Anterior view of mons and groins. Black arrow points to scar at drain site from groin dissection. B, View of vulva and perineum. Arrow points to surgical defect from local excision of the left Bartholin gland. Note regrowth of pubic hair.

Femoral neck fracture (avascular necrosis) can be a consequence of irradiation of inguino-femoral nodes lateral to the femoral vessels. Dose to the femoral neck should be limited to 45 Gy and (preferably) less, when such treatment is necessary. Because aseptic necrosis of the femoral neck following radiation is thought to be, at least in part, attributable to radiation injury to small vessels, the risk of this complication can probably be minimized by excluding most of the blood supply of the proximal femur (Fig. 52-29) from the initial radiation target volume when groin nodes are clinically and radiographically uninvolved. It remains unclear whether underlying osteoporosis (prevalent in the older women most likely to be afflicted with vulvar cancer) predisposes to postradiation femoral neck fracture, or whether the injury is exclusively microangiopathic damage with slow infarction. Smoking, etiologically implicated in the pathogenesis of vulvar cancer, may further contribute to the risk of microangiopathic injury. Bone fractures of the pelvic girdle or the femoral necks171 can be seen after radiation to the vulva and groins (Fig. 52-30). Treatment with parallel opposed anterior and posterior fields whose lateral extent includes the lateral borders of the femoral arteries will include all sentinel nodes74 while excluding most of the proximal femur and its blood supply from the external and internal circumflex arteries. Spontaneous microfractures of other bones may be seen when these bones have been included within high-dose volumes, particularly the ischial rami. The impact on quality of life from the resultant pain and prolonged immobility which often ensue may be severe, particularly from displaced fractures.

Major symptomatic late sequelae in bladder, rectum, and pelvic nerves can be expected to be rare when the dose guidelines shown in Table 52-9 are observed and the volumes of organs at risk are kept minimal. Radiation vaginitis with atrophy, itching, and discharge is usually mild and can be ameliorated with topical estrogen unless a substantial length of vagina has been included within a high-dose volume. Regular use of a vaginal dilator should be strongly encouraged in all patients who wish to retain the capacity for vaginal intercourse as well as to facilitate more comfortable pelvic examinations as part of follow-up surveillance. Focal injury to femoral arteries may occur, particularly if there are “hot” areas of dose inhomogeneity at the abutment of portals targeted to the groin nodes and the primary vulvar tumor (see Figs. 52-25 and 52-26). True radiation necrosis of the vulva is uncommon. Underlying vasculopathy may be a predisposing factor.189

Bartholin Gland Carcinoma

Malignancy arising from the Bartholin glands constitutes approximately 4% to 7% of vulvar malignancy. The criteria established by the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology (AFIP, Washington, D.C.) for the diagnosis of Bartholin’s gland carcinoma enjoy the broadest contemporary acceptance. A primary Bartholin’s gland cancer should show areas of apparent transition from normal elements to neoplastic ones on histologic study, should be histologically compatible with origin from the Bartholin glands, and should exist without evidence of primary cancer elsewhere. The Bartholin complex comprises a duct that is lined by squamous epithelium as it enters the distal vagina. The more proximal portions of the ductal system are lined by transitional epithelium and may be lined by columnar epithelium before arborization into secretory glandular elements. Various histologic tumor types may arise. Squamous cell carcinoma constitutes approximately 35% to 50% of cases, with adenocarcinoma only slightly less common.190–194 Adenosquamous carcinomas and transitional cell carcinomas make up a small minority of cases. Adenoid cystic carcinoma (cylindroma) represents a distinct subset thought to be less likely to spread to regional nodes; it is associated with a long natural history and late recurrences, which may be either local or hematogenous.195

Bartholin’s gland carcinomas have been reported in younger women and in association with pregnancy,190,191 although an etiologic relationship is not apparent. Often presenting with a mass deep in the labia with intact overlying skin, Bartholin’s gland carcinomas may be confused with a Bartholin cyst or abcess, particularly if the patient is young. MRI may confirm the primary site in the Bartholin complex when cancer has extended out the Bartholin duct to involve the distal vaginal mucosa and labia.