CHAPTER 1 Zenker’s diverticulum

Step 1. Surgical anatomy

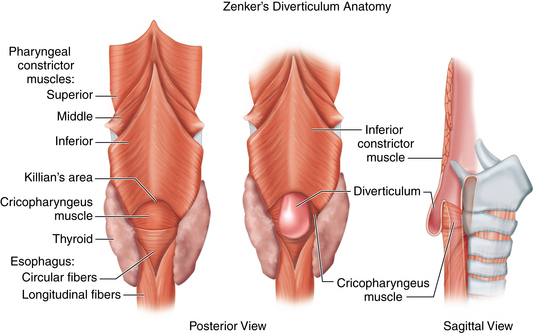

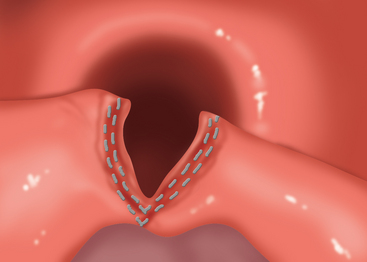

♦ Zenker’s diverticulum is a pulsion diverticulum that occurs between the lowermost fibers of the inferior pharyngeal constrictor and the cricopharyngeal (CP) segment. This segment is the upper esophageal sphincter (UES) and is composed of the cricopharyngeus muscle and a portion of the upper esophagus musculature (Figure 1-1).

♦ The etiology of Zenker’s diverticulum is a failure of timely opening of the CP segment. The diverticular sac forms in a relative weak spot in the posterior pharyngeal wall as contraction of the tongue and pharyngeal musculature builds pressure above a closed CP segment. Therefore, surgical correction of the condition must address not only the diverticulum but also the hypertonic or stenotic CP segment by performing a thorough myotomy.

♦ The transoral approach provides easy access to the diverticular sac and the CP segment (which lies within the common wall between the diverticulum and the cervical esophagus). However, the access to the segment is limited by the size of the diverticulum. Therefore, it is paradoxically easier to perform an adequate operation on patients with large diverticula as these may be stapled. Diverticula smaller than 2.5 cm may be inadequately divided by stapling because of limitations of the device and inadequate access to the CP segment. However, these smaller diverticula may be treated endoscopically with a CO2 laser in similar fashion.

♦ The availability of endostapling devices has decreased the concern of postoperative salivary leakage to a minimum. Improvements in laser technology allow this laser division to be performed safely without hemorrhage or stenosis.

Step 2. Preoperative considerations

Patient preparation

♦ Patients with Zenker’s diverticulum need a complete head and neck examination to identify other anatomic or neurologic causes for dysphagia. The input of a speech-language pathologist trained in dysphagia is extremely helpful. Many of these patients are elderly and may have more than one reason for their dysphagia. The symptom of dysphagia may not improve after repair of the Zenker’s diverticulum if other contributing causes are not identified preoperatively; in rare cases (listed later), symptoms may actually worsen.

Imaging

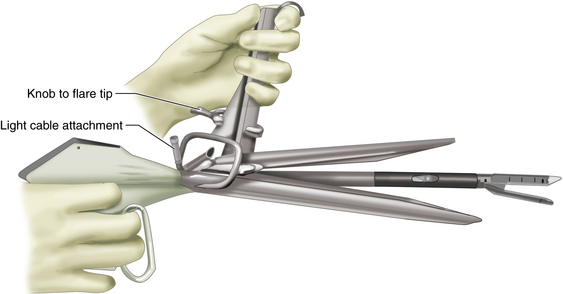

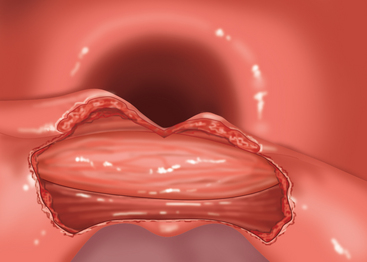

Modified barium swallow may identify pharyngeal dysphagia not seen in simple esophagram. Whichever study is performed, evaluation of bolus transit through the esophagus and lower esophageal sphincter (LES) is critical to rule out other disease processes that will not improve with surgery. When a straightforward diverticulum is seen, then the endoscopic diverticulectomy may be considered (Figure 1-2).

Anesthesia

♦ General anesthetic is used with the patient orally intubated. If performing laser division, a reflective, laser-safe endotracheal tube should be used. Oxygen concentration should be maintained below 30% and diluted with helium.

♦ Prophylactic antibiotics that cover oral flora are given in the event that perforation of the sac occurs or there is a need to convert to open repair. We use ampicillin/sulbactam (3 gms intravenously) or clindamycin (600 mg intravenously) for the patient who is allergic to penicillins.

Step 3. Operative steps

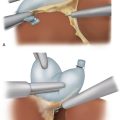

Staple-assisted procedure

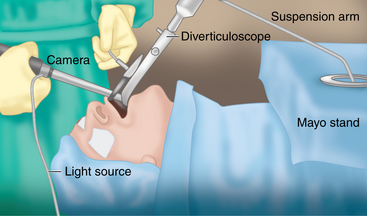

♦ The Kastenbauer-Wollenberg diverticuloscope (Figure 1-4) is inserted into the mouth and passed into the hypopharynx. The anterior (longer) bill of the diverticuloscope is inserted into the introitus of the esophagus and the diverticuloscope is opened, revealing the diverticulum and the common wall between the diverticulum and the cervical esophagus. The scope is held with a suspension arm positioned on the Mayo stand (Figure 1-5).

♦ Because of the size of the Endo GIA 30 stapler (Covidien, Mansfield, Massachusetts), it is not possible to perform the procedure under line-of-sight vision through the diverticuloscope. Therefore, the procedure must be done using an endoscopic camera and video monitor.

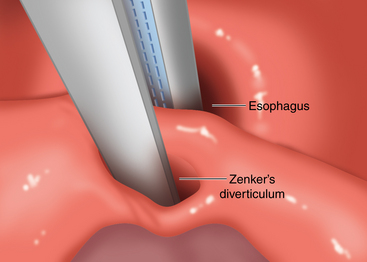

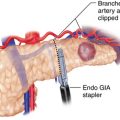

♦ The Endo stapler is inserted into the diverticuloscope under video guidance. We prefer to place the blade that contains the refillable cartridge into the cervical esophagus (Figure 1-6).

♦ The Endo stapler is fired and withdrawn, revealing the divided common wall between the diverticulum and the cervical esophagus with the divided cricopharyngeus muscle (Figure 1-7).

♦ The diverticuloscope is removed and the patient awakened from anesthesia.

Laser-assisted procedure

♦ Positioning and exposure is performed just as with the staple-assisted procedure. The face and eyes are protected with soaking wet towels and eye shields.

♦ An operating microscope is used to visualize the shared wall between the diverticulum and the esophagus. The CO2 laser is attached to a micromanipulator to direct the Helium-Neon (HeNe) aiming spot. Spot size is reduced to less than a millimeter, and the laser is used in Ultrapulse or SurgiTouch mode to maximize thermal relaxation time and minimize thermal damage. An adequate spot size (around 1 mm) will allow cutting and cauterization to proceed simultaneously.

♦ Incision begins through the mucosa over the superior aspect of the shared wall.

♦ Once opened, the transverse fibers of the cricopharyngeus may be seen. These are carefully divided to and, ultimately, through the fascia of the CP muscle at its inferior-most extent. The surgeon will know when this has been accomplished because the CP muscle will separate widely and retract into the lateral pharyngeal mucosa out of sight (Figure 1-8). A mucosal incision is made in the shared wall with a laser, showing muscle CP fibers.

♦ Beyond the CP muscle lies fibrous tissue posteriorly and smooth muscle of the cervical esophagus anteriorly. The upper portion of the esophageal muscle is divided as in open CP myotomy. This should not be taken to the same plane as the posterior wall of the diverticulum, but it may be taken to about 5 mm anterior to this. Posteriorly, near the anterior wall of the diverticulum, the fibrous bands should be divided to within about 5 mm of the base of the sac. Careful attention must be paid to avoid injury to the investing fascia of the pharynx and esophagus that surrounds the sac. Preservation of this fascia prevents perforation and mediastinitis (Figure 1-9).

♦ The mucosal incision is not closed. A 10 Fr styletted feeding tube is placed transnasally and passed into the esophagus under direct visualization. The diverticuloscope is removed carefully, the feeding tube secured to the nasal dorsum, and the patient is awakened.

Step 4. Postoperative care

♦ In medically suitable patients, the staple-assisted procedure can be done on an outpatient basis. A clear liquid diet is resumed immediately and advanced as tolerated by the patient. We observe these patients for 2 to 4 hours prior to discharge to ensure that there are no problems with resuming an oral diet.

♦ Following laser-assisted procedures, we do prefer to observe the patient overnight. Signs of perforation and mediastinitis include fever, chest pain, malaise, and severe odynophagia. If there are no signs of a problem, an esophagram may be performed with water-soluble contrast (e.g., Gastrografin) the following morning to exclude perforation. If a small leak is noted and the patient is minimally symptomatic, the patient may be observed with nasogastric feeding for 3 to 7 days. Larger leaks and hemodynamically affected patients should be explored.

♦ If cleared of leak by esophagram, we remove the feeding tube and discharge on a full liquid diet. Patients may advance to a soft diet over the next 2 weeks and an unrestricted diet within a month following the procedure. We encourage clear liquids following meals to prevent stasis in the posterior pharyngeal defect.

Step 5. Pearls and pitfalls

♦ The endoscopic repair of Zenker’s diverticula using an endostapling device is best done on patients with large sacs. We suggest that early on in a surgeon’s experience only diverticula larger than 3 cm be attempted. There does not seem to be an upper limit to diverticulum size for endoscopic treatment, and the endostapler may be fired multiple times to achieve adequate marsupialization. These patients may have more esophageal dysphagia, however.

♦ Care must be taken to ensure that the patient does not have other esophageal pathology in addition to the Zenker’s diverticulum. As this procedure will only address the dysphagia secondary to the diverticulum, failure to recognize other pathology will lead to suboptimal results. Thus, the input of an experienced speech/language pathologist and modified barium swallow rather than sole review of still images from an esophagram is prudent in the preoperative evaluation.

♦ Patients who cannot open their mouth widely, have large or loose upper incisor teeth, and cannot extend their neck well may be poor candidates for this approach, as the visualization of the diverticulum may be poor. It is often difficult to tell preoperatively who will be difficult to visualize. In questionable cases, the surgeon and patient may decide to proceed with traditional external approaches at the same procedure if the endoscopic approach is not feasible.

♦ Following the immediate healing period, postoperative esophagrams are not done unless the patient continues to be symptomatic. It is important to point out that the diverticular sac is not removed in this procedure. It is simply marsupialized into the cervical esophagus and a thorough cricopharyngeal myotomy is performed. Therefore, if a postoperative esophagram is performed, a diverticulum will still be present. For this reason the success or failure cannot be judged on radiographic studies but must be based solely on patient symptoms.

Adams J, Sheppard B, Andersen P, et al. Zenker’s diverticulostomy with cricopharyngeal myotomy, the endoscopic approach. Surg Endosc. 2001;15;1:34-37.

Gross N, Cohen J, Andersen P. Outpatient endoscopic Zenker diverticulectomy. Laryngoscope. 2004;114;2:208-211.

Lippert BM, Folz BJ, Rudert HH, et al. Management of Zenker’s diverticulum and postlaryngectomy pseudodiverticulum with the CO2 laser. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 1999;121(6):909-914.

Veenker EA, Andersen PE, Cohen JI. Cricopharyngeal spasm and Zenker’s diverticulum. Head Neck. 2003;25;8:681-694.