Chapter 20 Zenker’s Diverticula

![]() Video related to this chapter’s topics: Endoscopic Treatment of Zenker’s Diverticulum

Video related to this chapter’s topics: Endoscopic Treatment of Zenker’s Diverticulum

Epidemiology

ZD is a false diverticulum first described by Ludlow in 1769.1 X-ray studies have shown its incidence to be around 0.1% of upper gastrointestinal (GI) barium studies.2 Of patients, 80% are older than 60 years.3 ZD is more frequent in men than in women.3 The occurrence in children is rare,4 and no differences have been mentioned concerning race or geographic areas.

Pathogenesis

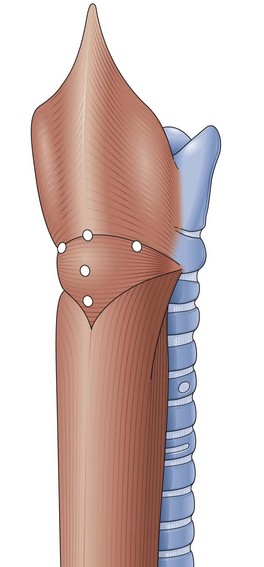

ZD develops as a result of the cooccurrence of weak points in the posterior wall of the hypopharynx and a lack of coordination between the pharyngeal constrictor and the cricopharyngeal muscles.5 Fibrosis of the cricopharyngeal muscle and the striated muscle of the upper esophagus has been shown more recently as the cause of such incoordination.6,7 Contraction of the pharyngeal constrictor muscle combined with the absence of relaxation of the cricopharyngeal muscle results in difficult passage of a food bolus and an increase in local pressure, which makes the mucosa and submucosa bulge through the weak sites between the descending fibers of inferior constrictor and transverse cricopharyngeal muscles, which constitute the distalmost part of the inferior constrictor (Fig. 20.1). Some authors believe that the incomplete sphincter opening is more likely than the incoordination to cause dysphagia.6 The mucous membrane sac can also pass through or immediately beneath the cricopharyngeal muscle.

Clinical Features

There is a well-established relationship between the anatomic changes and clinical symptoms.8 When a ZD is small, the patient has the sensation of having a foreign body in his or her throat. Throat irritation with excessive mucus is also common. As the ZD increases in size, regurgitation of food and mucus begins to occur after meals and when the patient lies down. If the sac is very large and the opening is transverse, the preferential route of food would be into the ZD. Symptoms of obstruction appear in this case, and many patients lose a significant amount of weight. In the second and third phases of the disease, pulmonary complications are common and sometimes repetitive, usually obliging the patient to seek treatment. Difficulty swallowing large food boluses, medication, or devices such as endoscopic capsules can be the earliest indicators for the detection of ZD.9

Pathology

The diverticulum arises as a protruding area at the weak points of the muscular structures of the hypopharynx and then increases progressively. The wall of the sac is formed only by the mucosa and submucosa. In contrast to esophageal diverticula, ZD is not a true diverticulum. As a diverticulum, ZD forms a pouch and descends along the left side of the neck; however, it may be present on either side. In advanced phases of the disease, the mucosa may show esophagitis. The incidence of cancer seems to be higher in patients with ZD than in patients without this disease.10,11 ZD is usually found in association with some other esophageal disease, such as hiatal hernia, gastroesophageal reflux, esophageal membranes in 50% of cases, achalasia, and polyps.12,13

Differential Diagnosis

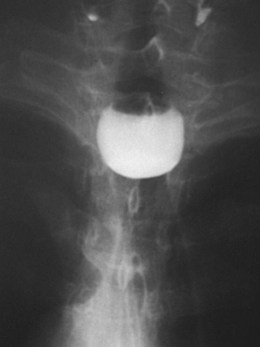

Radiography is very useful when the patient experiences some difficulty in swallowing solid medication, such as a pill, and it is important in advanced phases of ZD. If the sac is not small, the diagnosis is easily established in the anteroposterior projection (Fig. 20.2).14 The sac lies in the midline and extends to the left. However, in the case of a small and nonretentive ZD, the lateral projection is important (Fig. 20.3). When aspiration of a bolus is suspected, an x-ray study without barium is needed. In such a case, iodine contrast material should be used to avoid complications secondary to aspiration of barium into the lung. Sometimes it is necessary to clear the ZD lumen from retained foods to avoid filling defects that may look like mucosal lesions on imaging.

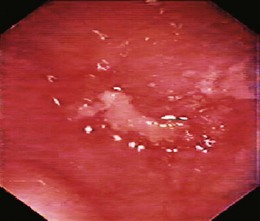

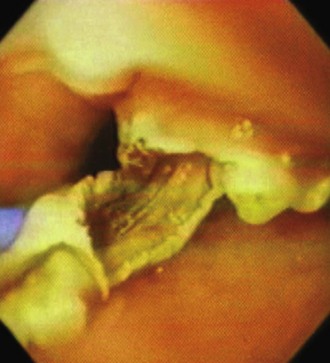

Endoscopy is the alternative diagnostic test. For many years, endoscopy was not recommended; however, it is a very important means of diagnosis and treatment. Even when the diagnosis of ZD has been established, endoscopy should be performed because alterations in the mucosa can occur, and a biopsy is essential (Fig. 20.4). The incidence of cancer is higher in ZD mucosa than in normal esophageal mucosa. In early phases of the disease, when ZD cannot yet be detected, the difficulty found in inserting the endoscope into the esophagus is the most common basis for the suspicion of ZD. Because endoscopy is the first option of most physicians, when a patient presents with upper GI tract symptoms, the possibility of a ZD must be considered in case of such difficulty.

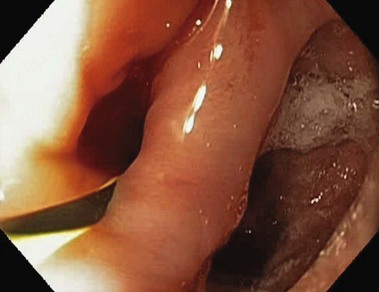

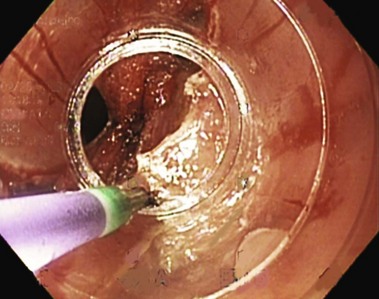

The endoscopy procedure is not dangerous in experienced hands, and insertion of the endoscope into the esophageal lumen is usually achieved often with the help of a flexible accessory used as a guide (Fig. 20.5). This method allows examination of the ZD mucosa and even the biopsy specimen. As the ZD increases progressively from a small protruding area to a sac, it usually descends down the left side of the neck. However, it may manifest on either side of the neck where an alteration is detected. A long fast period should be always recommended before the endoscopy procedure. During the diagnostic procedure, in cases of superficial trauma or biopsy, antibiotics should be prescribed. If a perforation is suspected in the case of failure in attempting to perform an endoscopy in a patient with a ZD, an upper GI barium study is not advised because the preferential way for the contrast material to flow would be the perforation opening secondary to the alteration and dysfunction of the cricopharyngeal muscle. Although endoscopic examination is helpful, it can increase pneumomediastinum.

Treatment

When the initial complaint of the patient is difficulty swallowing and ZD can be suspected from the x-ray study, improvement may result from dilation. In advanced cases, the classic treatment has been surgery. Resection of ZD and cricopharyngeal myotomy is the “gold standard,” although inversion of the sac has been performed by some surgeons. Cricopharyngeal myotomy is a fundamental part of the procedure, and this is probably the reason for the failure of treatment with resection of the diverticulum only.15

For many years, surgery was performed in two stages to avoid mediastinitis and pulmonary complications. However, most surgeons prefer a one-stage operation using a tube inside the esophagus or an endoscope inside the diverticulum to determine the ZD position, preventing excessive resection of tissue with subsequent stricture. For a small ZD, some authors recommend cricopharyngeal myotomy only. Although this procedure is associated with diverticulopexy or diverticulotomy, it is an important step for the treatment of large ZD. The most frequent complication of surgery is the development of a pharyngocutaneous fistula in the early postoperative course. When spontaneous healing does not occur, endoscopic dilation of the esophagus and fibrin injection around the internal orifice with or without placement of clips at the same site have been successful. A randomized study by Bowdler and Stell16 compared inversion with resection in association with cricopharyngeal myotomy. Better results and lower incidence of fistulas were obtained with inversion. Other complications of the conventional approach are mediastinitis, laryngeal paralysis, stricture, and recurrence.

Endoscopic treatment is not new. In 1917, Mosher10 had described an endoscopic transoral diverticulotomy, but this method was soon abandoned because of complications. In 1960, Dohlman and Mattson17 presented their endoscopic technique using electrocoagulation to divide the wall between the esophagus and the diverticulum. Another transoral technique was proposed by Collard and associates18 in 1993 using an Endo GIA 30 2.5-cm stapler to cut the muscle bar. In this case, the cut edges were stapled with metallic clips, which avoids contamination of the mediastinum and ensures hemostasis of the wound edges. However, this procedure requires general anesthesia, and the postoperative course can be uncomfortable. In addition, it is uncertain if a sufficient myotomy can be performed. Because of the design of this device, usually a small pouch remains at the bottom of the ZD. More recently, a simple, low-cost endoscopic technique was described that is performed without general anesthesia and can be used in most cases with good results and a low morbidity rate.

Endoscopic Treatment of Zenker’s Diverticulum

Technique

Preparation

Endoscopic treatment of ZD19 should be performed in fasted patients. Patients with a deep ZD must have only liquid foods on the day preceding the endoscopic treatment, and just before the operation, all patients must use a liquid antiseptic mouthwash and gargle repeatedly. Antibiotic (2 g cephalosporin) is given intravenously before the procedure. Diverticulotomy can be performed under monitored anesthesia care and topical anesthesia with lidocaine.

Diverticulotomy

The transverse fibers of the cricopharyngeal muscle are important to target as the endpoint of the septotomy and are usually clearly seen across the bottom of the diverticulum (Fig. 20.6). Analgesics are needed after the procedure. Patients are allowed to resume oral intake of liquid about 18 hours after the procedure and proceed to a regular diet as tolerated. Some authors suggest that a dilation procedure before diverticulotomy makes the procedure easier.

Interest in the endoscopic treatment of ZD has been increasing. Technique variations are available that may make the septotomy easier and safer. However, some of these alternative options increase the cost of the procedure. If the endoscopist detects a good exposure and has a reasonable experience, he or she should perform the endoscopic treatment of ZD without using other devices. Noncontact cutting has been reported using the argon plasma coagulator.20 The simplest accessory is described by Sakai and colleagues.21 The device is a transparent cap (MH589; Olympus, Tokyo, Japan) that can be attached to the distal end of the forward-viewing endoscope similar to caps used for mucosectomy during the cut.21 The cap concept has been developed further with the addition of cutting wires that allow the septum to be straddled with a gap in the cap cylindric wall at the upper end of which is an electrosurgical cutting wire.22 It improves the septum exposure almost without trauma (Fig. 20.7). Another device is a diverticuloscope23,24; it consists of a soft rubber or plastic overtube with a distal end designed to provide good septum exposure and protect the walls.

The pig pharyngeal pouch anatomy accurately mimics ZD. This pouch has been shown to serve as an effective training model to learn the septotomy technique.25

Results

In the postoperative course, bleeding is rare and has been controlled endoscopically. Cervical emphysema is not rare and can be encountered when there has been complete section of the septum. It may increase if the patient coughs just after the incision has been made. In our first series, 83% of the patients began oral intake of liquids and ice cream on the first day after the endoscopic diverticulotomy and of solid food in the subsequent days. In two patients, endoscopic control 1 month later revealed stenosis of the esophageal entrance, and a new section had to be performed for resolution of the dysphagia recurrence. In case of recurrence, the preference now is to perform two lateral incisions, not only one in the middle (Fig. 20.8). However, it is important that the incisions be performed not far from the middle line to avoid laryngeal alterations. Serious complications such as mediastinitis and fistula can occur, but they are rare with endoscopic treatment.

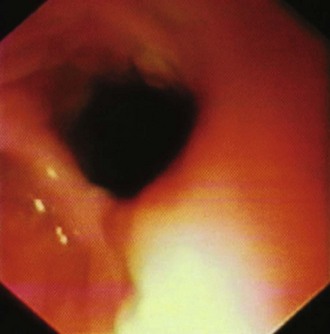

Follow-up for our first series ranged from 1 day to 1 year. In many cases, endoscopic therapy results in a shallow remaining pouch at the bottom of the ZD, despite an apparent complete section (Fig. 20.9). Rarely, a residual septum is not seen. Even in patients without symptoms, contrast study has shown that the ZD has not disappeared completely and is not a useful long-term follow-up assessment tool; because of this, some authors distinguish between clinical and radiologic recurrence.26 In successful cases, manometry has revealed a reduction of the upper esophageal sphincter pressure.15 Despite various technique modifications, it is impossible to determine the best treatment for symptomatic patients with ZD because comparative studies are difficult to accomplish given the rare prevalence of the disorder.

Future Trends

Endoscopic treatment should be a strong consideration with available expertise in interventional endoscopy. The porcine pharyngeal pouch should be included in training and competency for septotomy. Conventional surgery can be reserved for failure of septotomy. Stapling or suturing of the septotomy edges is desirable, as in the endoscopic staple-assisted esophagodiverticulostomy proposed by Collard and colleagues18 and Scher and Richtsmeier.27 The development of freehand suturing may allow the closing of the edges of the septum once the endoscopic device becomes clinically available.28 This closure would ensure hemostasis and avoid perforation, which is the main complication of the endoscopic treatment of ZD.

1 Ludlow A. A case of obstructed deglutition from a preternatural dilatation of a bag formed in pharynx. Med Observations Inquiries. 1767;3:85-101.

2 Shaw DW, Cook IJ, Gabb M, et al. Influence of normal aging on oral-pharyngeal and upper esophageal sphincter function during swallowing. Am J Physiol. 1995;268:G389-G396.

3 Holinger PH, Schild JA. The Zenker’s (hypopharyngeal) diverticulum. Ann Otol. 1969;78:679-688.

4 Meadows JAJr. Esophageal diverticula in infants and children. South Med J. 1970;63:691-694.

5 Bell C. Surgical observations. London: Longmans, Greene; 1816.

6 Cook IJ, Jamieson GG, Blumberg P, et al. Pathogenesis and treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum. Chirurgia. 1990;116:673-678.

7 Lerut T, van Raemdonck D, Guelinckx P, et al. Zenker’s diverticulum: Is a myotomy of the cricopharyngeus useful? How long should it be? Hepatogastroenterology. 1992;39:127-131.

8 Lahey FH, Warren KW. Esophageal diverticula. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1954;98:1-4.

9 Knapp AB, Ladetsky L. Endoscopic retrieval of a small bowel enteroscopy capsule lodged in a Zenker’s diverticulum. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2005;3:xxxiv.

10 Mosher HP. Webs and pouches of the esophagus, their diagnosis and treatment. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1917;25:175-187.

11 Pierce WS, Johnson J. Squamous cell carcinoma arising in a pharyngoesophageal diverticulum. Cancer. 1969;24:1068-1078.

12 Gage-White L. Incidence of Zenker’s diverticulum with hiatus hernia. Laryngoscope. 1988;98:527-530.

13 Gullane PJ, Willet JM, Heeneman H, et al. Zenker’s diverticulum. J Otolaryngol. 1983;12:53-57.

14 Wheeler D. Diverticula of the foregut. Radiology. 1947;49:476-482.

15 Broll R, Kramer T, Kalb K, et al. Manometric follow-up after resection of Zenker’s diverticulum. Z Gastroenterol. 1992;30:142-146.

16 Bowdler DA, Stell PM. Surgical management of posterior pharyngeal pulsion diverticula: Inversion versus one-stage excision. Br J Surg. 1987;74:988-990.

17 Dohlman G, Mattson D. The endoscopic operation for hypopharyngeal diverticula. Ann Otol Rhinol Laryngol. 1960;71:744-752.

18 Collard JM, Otte J, Kestens PJ. Endoscopic stapling technique of esophagodiverticulostomy for Zenker’s diverticulum. Ann Thorac Surg. 1993;56:573-576.

19 Hashiba K, Paula AL, Silva JGN, et al. Endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 1999;49:93-97.

20 Rabenstein T, May A, Michel J, et al. Endoscopy. 2007;39:141-145.

21 Sakai P, Ishioka S, Maluf-Filho F, et al. Endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum with an oblique-end hood attached to the endoscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2001;54:760-763.

22 Seaman DL, Levy JLM, Gostout CJ, et al. A new device to simplify flexible endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2008;67:112-115.

23 Costamagna G, Iacopini F, Tringall A, et al. Flexible endoscopic Zenker’s diverticulotomy: Cap-assisted technique vs. diverticuloscope-assisted technique. Endoscopy. 2007;39:146-152.

24 Evrard S, Le Moine O, Hassid S, et al. Zenker’s diverticulum: A new endoscopic treatment with a soft diverticuloscope. Gastrointest Endosc. 2003;58:116-120.

25 Seaman DL, Levy JLM, Gostout CJ, et al. An animal training model for endoscopic treatment of Zenker’s diverticulum. Gastrointest Endosc. 2007;65:1050-1053.

26 Bertelsen S, Aasted A. Results of operative treatment of hypopharyngeal diverticulum. Thorax. 1976;31:544-547.

27 Scher RL, Richtsmeier WJ. Endoscopic stapled-assisted esophagodiverticulostomy for Zenker’s diverticulum. Laryngoscope. 1996;106:951-956.

28 Moran EA, Gostout CJ, Bingener J. Preliminary performance of a flexible cap and catheter-based endoscopic suturing system. Gastrointest Endosc. 2009;69:1375-1383.