Wrist & distal forearm

Normal anatomy

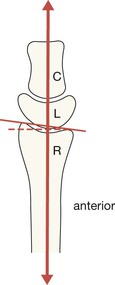

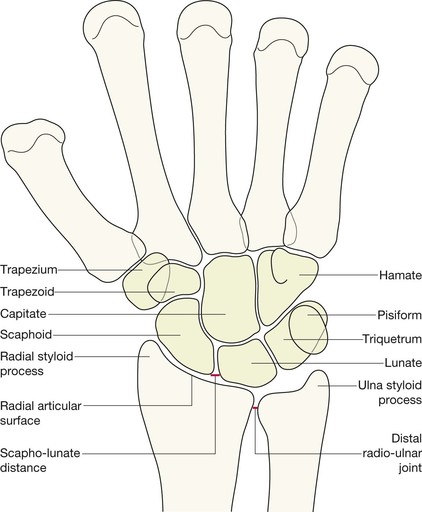

PA projection: bones and joints

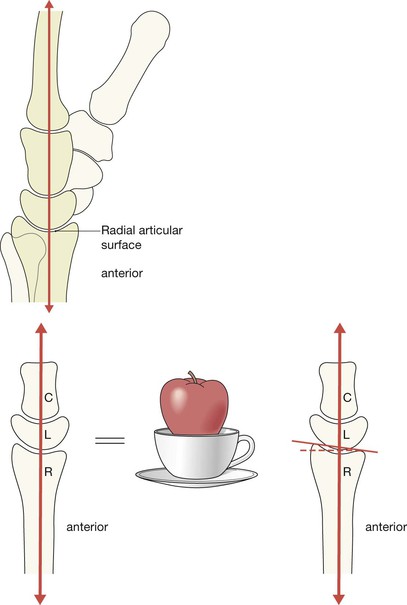

The articular surface of the radius lies distal to that of the ulna in 90% of normal people.

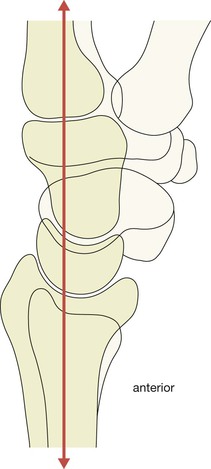

The carpal bones are arranged in two rows, bound together by strong ligaments:

▪ The joint spaces are uniform in width: 1–2 mm wide in the adult.

▪ Adjacent bones have parallel/congruous surfaces.

▪ Abnormally wide spaces are likely to indicate damaged ligaments.

Lateral projection: bones and joints

The dorsal cortex of the distal radius is completely smooth—no crinkles, no irregularity. This cortex should be as smooth as a baby’s bottom.

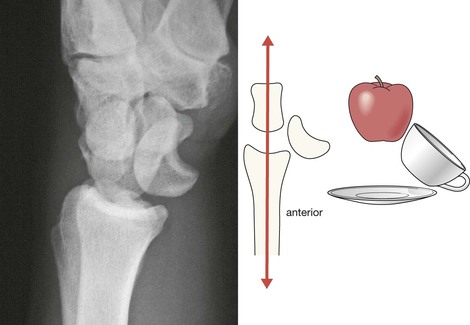

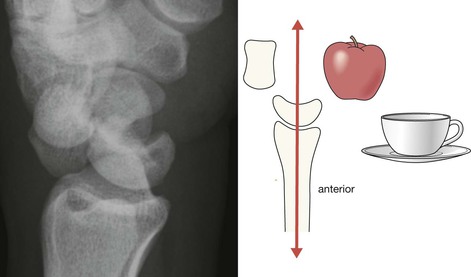

The alignment of the carpal bones may appear confusing but identifying the important anatomy is actually very simple. Don’t worry about the overlapping bones. Just think: apple, cup, saucer.

Analysis: the checklists

The PA view will appear fairly comforting to an inexperienced observer because all of the carpal bones are clearly shown. The lateral radiograph may appear terrifyingly complex and difficult to analyse because of the numerous overlapping bones. There is a very clear message: do not be afraid!

The lateral view is diagnostically very, very, important, so we will show you how to quickly and confidently analyse every lateral radiograph using a simple checklist.

The PA view

Analysis: ask yourself five questions.

Questions 1–4 apply to all adults. Question 5 applies to all children.

1. Is the radial articular surface and/or the ulna styloid process whole and intact?

No = undisplaced fracture.

2. Does the radial articular surface lie distal to the ulna?

No = suspect disruption at the radio-ulnar joint.

3. Is the scaphoid bone intact and normal?

No = fracture.

4. Is the scapho-lunate distance less than 2 mm wide?

No = suspect a tear of the scapho-lunate ligaments (p. 147).

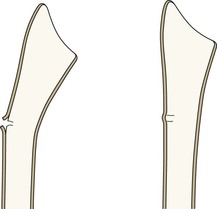

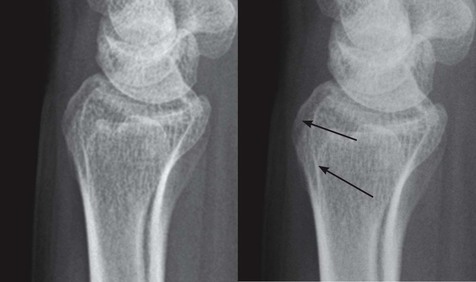

5. In children: does the radial cortex show any angulation or any suggestion of a localised bulge?

Yes = Greenstick or Torus fracture.

The lateral view

Analysis: ask yourself five simple questions on each and every lateral view. No exceptions.

If you ask and correctly answer these five questions you will detect all the subtle and clinically important abnormalities.

1. Is the radial articular surface intact?

No = undisplaced fracture.

2. Is the dorsal cortex of the distal radius smooth? Specifically:

□ Is the cortex as smooth as a baby’s bottom?

□ No crinkle, no angulation, no bulge, no buckling?

□ Are you sure? Check the dorsal cortex one more time.

No, it is not smooth = undisplaced fracture.

3. Is the palmar tilt (normal range 2–20°) of the articular surface of the radius normal?

No = suspect an impacted fracture.

4. Is there a bone fragment lying posterior to the carpal bones?

Yes = Triquetral fracture.

5. Is there a bone sitting in the cup of the lunate?

No = carpal dislocation involving the lunate (pp. 148–150).

The scaphoid series

Many undisplaced scaphoid fractures are not visualised on the two standard (wrist) views. Two extra views produces a better return. Therefore, a four view scaphoid series is essential and should be requested whenever there is ‘snuffbox’ tenderness:

The two additional images will vary between Emergency Departments. Importantly, two of the four projections will always include a true PA and a true lateral of the wrist.

Scaphoid fractures are mainly hairline fractures and lucent; they are not sclerotic. Occasionally the fracture is displaced.

Analysis: ask yourself three questions.

1. Does the scaphoid appear intact on each of the four views?

No = fracture (see p. 144).

2. Is the distal radius—particularly the styloid process—intact?

No = fracture (see pp. 136–141).

AND

3. Have I checked the PA and lateral views step-by-step (see pp. 128–130)?

No = start checking.

Wrist myths

Inevitably there will be some soft tissue swelling over the site of an injury due to simple bruising, a ligamentous injury, a fracture, or a combination of all of these. This soft tissue swelling on the radiograph is not particularly helpful in terms of radiological diagnosis. There have been claims that the appearance of some soft tissue fat stripes around the wrist can be helpful, but this is not the case1.

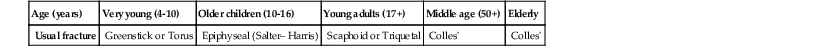

The common fractures

Fractures of the distal radius

These injuries result from a fall on the outstretched hand.

Subtle fractures/careful diagnosis

▪ A crinkle, or any irregularity of the cortex of the dorsal aspect of the distal radius.

▪ An impacted and undisplaced fracture:

□ The only abnormality may be a very slight increase in the density of the radial metaphysis and/or

□ Loss of the normal palmar tilt of the radial articular surface (see p. 127).

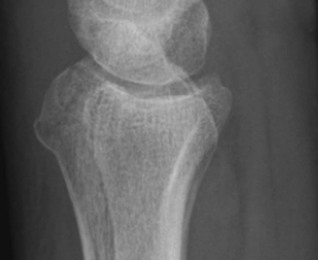

Fractures of the distal radius in children

Sometimes these fractures are obvious. Many are very subtle.

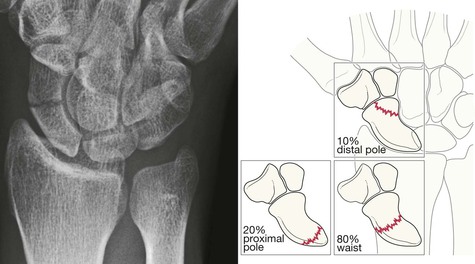

Scaphoid fracture

This injury mainly affects young adults (see p. 136). Carpal bone injuries—including scaphoid fractures—are very rare in children.

A recent scaphoid fracture is never sclerotic (ie white/dense).

Most scaphoid fractures will be evident on the initial scaphoid series3. Contrary to conventional teaching, the number of occult fractures revealed by repeat radiography at 10 days is very low4,5. Persisting clinical suspicion warrants an MRI, not more plain film radiography.

Clinical impact guideline: If a scaphoid fracture is initially overlooked and the patient is managed incorrectly then any of the following may occur: non-union, delayed union, avascular necrosis (AVN) of the proximal fragment, or osteoarthritis.

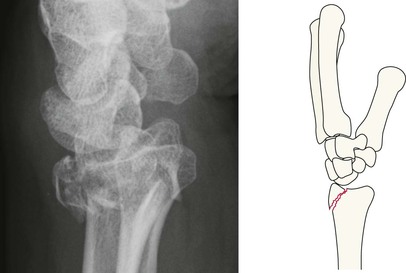

Triquetral fracture

A small fragment or flake of bone lying posterior to the proximal row of the carpus on the lateral view invariably represents an avulsion fracture of the triquetrum (the triquetral bone). This fracture accounts for approximately 20% of all carpal bone fractures5.

Occasionally a triquetral fracture may occur when there is a perilunate dislocation of the carpus6. This emphasizes the importance of two of our basic principles:

1. Avoid a premature “satisfaction of search” approach. Complete the checklist.

2. Always check the saucer, cup, apple alignment on every lateral radiograph. Remember: the cup of the lunate should never be empty (see pp. 148–150).

Clinical impact guideline: if a solitary triquetral fracture is detected, the patient can be reassured that the injury will be treated conservatively, mainly by providing pain relief, and an excellent outcome is anticipated.

Subluxations and dislocations

Distal radio-ulnar joint subluxation

Disruption of this joint is a relatively frequent finding with a Colles’ fracture, occurring in 18% of cases7. Isolated traumatic dislocation or subluxation of this joint is rare.

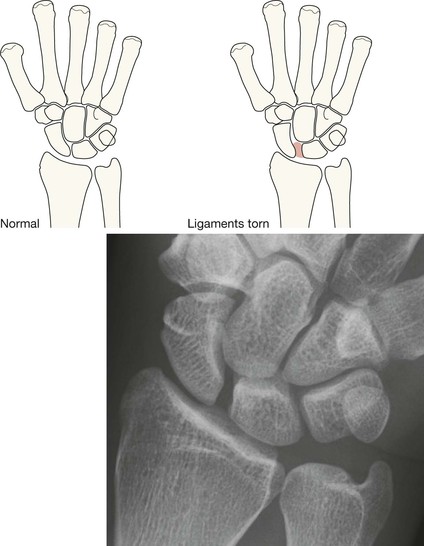

Scapho-lunate separation

The scapho-lunate joint is particularly susceptible to ligamentous injury. In adults, following an injury to the wrist, any widening of the normal space (normal = 2 mm)between the lunate and the scaphoid bones on the PA radiograph is strongly suggestive of a ligamentous tear.

This injury is particularly common in the elderly when the ligaments may be friable.

Clinical impact guidelines: The syndrome of chronic wrist pain located around the scapho-lunate joint due to scapho-lunate instability is a very troublesome problem9. In the elderly, this injury will usually be treated conservatively. In younger patients, surgery will be considered in order to restore full function and a pain free wrist.

Rare but important injuries

Fractures of the other carpal bones

▪ A fracture of the hamate may occur when a fist puncher has injured the base of his 4th or 5th metacarpal (pp. 167–168).

▪ The hook of the hamate may also fracture as a result of a direct blow to the carpus or as an avulsion injury associated with racquet sports or a golf swing5,6.

Subluxation/dislocations of the carpus

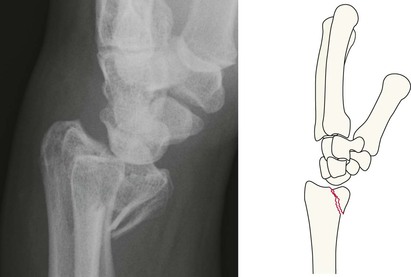

These injuries are infrequent but are usually centred around the lunate bone. The following rule is the key to their detection, and must be applied to all lateral views:

The cup of the lunate should never be empty.

Lunate dislocation and perilunate dislocations of the carpus6,10,11

These dislocations are not difficult to recognise provided that the basic anatomy on the lateral view is properly understood (see p. 127). The distal radius, the lunate and the capitate articulate with each other and lie in a straight line. Consequently, the question to ask on all lateral views is:

‘Does a bone (the capitate) sit in the cup of the lunate?’

Carpal subluxations6,8

Ligamentous tears or ruptures can affect any of the small joints of the carpus. Such injuries may result in carpal instability, pain, and reduced function.

Normally, the joint spaces between the intercarpal joints measure no more than 2 mm in the adult. Widening of any of these spaces raises the possibility of an intercarpal subluxation. In addition, subluxation will be suggested because adjacent bones do not have parallel or congruent surfaces.

Help is always available. If you are in any doubt as to whether there is true widening at a carpal joint, you can always obtain a radiograph of the uninjured wrist. This will allow comparison between the injured and uninjured sides.

Clinical impact guideline: Referral to a hand surgeon for a specialist clinical evaluation will be necessary when joint widening or lack of parallelism of adjacent surfaces is noted.