4.1 Wound management

Introduction

Open wounds account for up to one third of paediatric emergency presentations; two thirds of open wounds occur in boys, and 40% involve a fall. The scalp and face account for more than 50% of all open wounds, and about 30% occur on the hands.1–4 The goals of management of these wounds are to avoid infection, minimise discomfort, facilitate healing and minimise scar formation. Meticulous attention to wound care and repair should ensure the best possible outcome and functional result. In children this often requires sedation in addition to adequate local anaesthesia and analgesia. Universal precautions should always be followed when assessing or managing any wound. Gloves (preferably sterile), drapes and eye protection are mandatory.

Wound infection

Wound infection is relatively uncommon, occurring in about 5% of wounds presenting to emergency departments (EDs). In general, a wound in a child is less likely to become infected than a similar wound in an adult. Identified risk factors for infection include severe wound contamination, inadequate wound cleansing, inadequate debridement of dead tissue (especially in crush injuries), use of subcutaneous sutures, larger laceration (>5 cm) and site of injury. Specific sites identified as infection risks include axillae, perineum or groin, and feet. In general, limb wounds are at increased risk compared to head and neck wounds.3,5,6

Classification of wounds

Lacerations

Lacerations are the most common type of wound seen in the paediatric age group.6 The edges are usually ragged. If the wound penetrates into the dermal capillaries it will bleed and if it extends into the subcutaneous tissue it will gape. Lacerations can be caused by tension on the skin (usually seen in areas with significant subcutaneous tissue) or by compression of the skin between an object and bone. There is always damage done to surrounding tissues and healing is therefore delayed. Compression injuries usually have more surrounding tissue damage and thus tend to heal more slowly.

Evaluation of the patient with a laceration

History

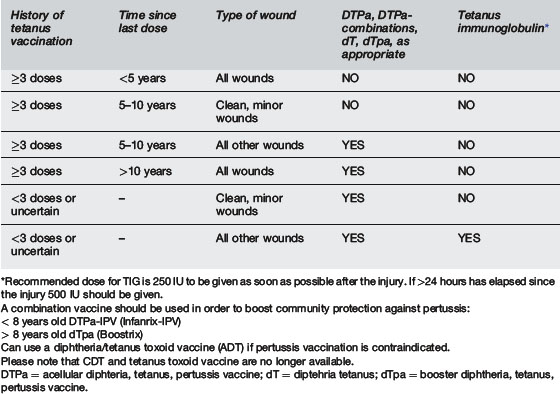

The health status of the patient should be explored, especially with regard to chronic illnesses that may impact on wound healing – such as diabetes mellitus, obesity, malnutrition, chronic renal impairment, cyanotic congenital heart disease, chronic respiratory illness, tumours, and bleeding disorders.3 Immunisation history should be obtained and further tetanus vaccination guided by the recommendations of the National Health and Medical Research Council (Table 4.1.1).7 Current medications are important for both drug interactions with antibiotics that may be prescribed and for medications that may interfere with wound healing – such as immunosuppressive drugs and corticosteroids. A history of allergies must be determined prior to use of cleansing agents, dressings and tapes and prescription of medication. A history of latex allergy should be specifically sought. In wounds that require management under general anaesthesia or sedation a history of when the child last ate or drank is important. Non-accidental injury should be considered, especially when the history and injury are inconsistent.

Examination

The co-operation able to be gained and comprehension level of the child influence wound examination and the information gained. Distraction techniques, adequate topical anaesthesia and appropriate use of sedation can all aid in wound assessment. A calm, unhurried, friendly approach, involving the parents, will maximise the chances of co-operation. Examination of the wound should be done with optimal lighting and with bleeding minimised. Examination of function, sensation and circulation distal to the wound is best performed prior to exploration of the wound and prior to regional anaesthesia.8–10

Investigation

If presence of a foreign body is expected radiological investigation is advised. In wounds caused by glass, all but superficial wounds should be investigated with plain soft tissue X-ray of the region to exclude a glass foreign body. Most glass foreign bodies more than 2–3 mm in size should be visible. If a radiolucent foreign body is suspected, ultrasound can be useful to both confirm the presence of the foreign body and provide a guide to its depth and location in the wound.9–11 Other investigations should be determined by the findings of possible injuries to adjacent structures, such as bony X-rays for fractures.

Treatment of wounds

Wound anaesthesia

Analgesia and sedation are discussed in more detail in Section 20. Anaesthesia is required to adequately examine and then treat most wounds. Often, in children, analgesia and sedation will also be necessary, depending on the location of the wound, the involvement of underlying structures, and the age and anxiety of the child.

Topical anaesthetics include ALA (adrenaline, lidocaine and amethocaine (tetracaine)) – commonly known as LET (lidocaine, epinephrine and tetracaine) in North America, or EMLA cream (eutectic mixture of local anaesthetics) – manufactured by AstraZeneca. ALA is highly effective on facial and head wounds but less so on limb wounds. It has replaced TAC (tetracaine, adrenaline and cocaine) in most institutions. Due to the vasoconstricting properties of adrenaline (epinephrine) these anaesthetics should not be used in areas of end arteries (finger tips, nose, lips, ears, genitalia). EMLA has been shown to be safe and effective when applied to limb wounds. Topical anaesthetics should be applied in the wound either as a liquid dripped onto a pledget of cotton wool placed into the wound or as a methylcellulose gel. The wound is then covered with an occlusive impermeable dressing and adequate anaesthesia is usually obtained within 30 minutes.12–17

Local infiltration is the classical method of anaesthetising a wound. The anaesthetic is injected into the wound margins. Pain of injection can be minimised by using warmed anaesthetic, buffering the drug with sodium bicarbonate (mix 10 mL of 1% lidocaine with 1 mL of 8.4% sodium bicarbonate), infiltrating slowly, using the lowest concentration possible, and using needles sized 25 gauge or smaller. The most commonly used local anaesthetic is lidocaine 1 or 2% with or without adrenaline (epinephrine) 1:100 000. The onset of action is rapid, with duration of action of 30 minutes to 1 hour. Addition of adrenaline (epinephrine) is useful to prolong the duration of action and help minimise bleeding; however, adrenaline (epinephrine) should be avoided in regions of end arteries (fingers, nose, lips, ears, genitalia), and its use may increase the risk of infection. The safe dose of plain lidocaine is 3 mg kg–1 or 6 mg kg–1 for lidocaine mixed with adrenaline (epinephrine).3

Sedation is often required when treating lacerations in children. Options for sedation include benzodiazepines – such as midazolam or diazepam, fentanyl, nitrous oxide, ketamine, or propofol. Sedation should only be undertaken by personnel experienced in its use and able to manage the complications of airway compromise, oxygen desaturation and respiratory depression. Adequate equipment to deal with these complications should also be available. Some form of physical restraint may also be necessary to prevent excessive movement during repair; however, the aim must be to provide adequate analgesia and anxiolysis.13,18

Wound preparation and cleansing

Hair near the wound should only be removed if it interferes with the meticulous closure of the wound. If hair removal is desired the hair should be clipped, not shaved, as shaving disrupts hair follicles and increases the incidence of wound infection.19 Eyebrow hair should not be removed because this may lead to abnormal or delayed regrowth.

Once the wound is adequately anaesthetised it should be thoroughly cleaned. Irrigation is the method of choice for removing dirt and bacteria from wounds. In hospital, saline (0.9%) is the irrigation solution of choice, as it causes no tissue damage, but tap water can be used.20 The ability of irrigation to decontaminate a wound is directly related to pressure of the irrigating stream, the size of the particles to be removed, and the volume of irrigant. At least 100–200 mL per 2 cm of laceration are required. The fluid should be injected from a 30–60 mL syringe via an 18 to 20 gauge cannula. Higher pressures should be avoided as they may cause tissue damage and increase the incidence of wound infection.21,22 The volume and pressure of irrigation should be modified as necessary according to the location and cause of the wound. High-pressure irrigation does not enhance the dissemination of bacteria into soft tissue wounds, but excessive use can cause local tissue oedema enhancing risk of infection. Use of a device to minimise splashing of the irrigant is desirable and wearing of gloves, goggles and gown mandatory.21,22

Antibiotic prophylaxis

The use of prophylactic antibiotics in wound care is controversial. Decontamination with appropriate irrigation techniques is more beneficial than the use of prophylactic antibiotics.2,9,23,24 When indicated (Table 4.1.2), antibiotics should be given as soon as possible. The initial dose should be given intravenously and be relatively large to provide rapid reliable high tissue concentrations. The first dose should be given before wound closure to ensure an effective concentration of antibiotic in the wound tissue fluid at the time of wound closure. When choosing an antibiotic the likely causative organisms should be borne in mind: the organisms contaminating the wound and the commensal organisms found in that region of the body. In general, bites and wounds in regions with high bacterial counts (hands, feet, groin) should be treated with antibiotics to cover Staphylococcus epidermidis, S. aureus and Streptococcus sp. The likelihood of anaerobic bacteria needs to be considered. Specific circumstances also need to be borne in mind. Patients at risk of endocarditis should have all wounds treated with antibiotics to cover S. aureus and S. epidermidis. Ampicillin/amoxicillin is the currently recommended drug in Australia. However, in communities where the incidence of penicillin resistance is high a cephalosporin and an aminoglycoside are recommended.

Tetralogy of Fallot

Ventricular septal defects

Coarctation of the aorta

Damaged heart valves

Wounds associated with fractures, tendon or muscle involvement should be considered for prophylaxis, as should large wounds, wounds with significant devitalised tissue such as crush injuries and stellate lacerations. Wounds contaminated with faeces should be treated with coverage of coliforms and anaerobic bacteria. Wounds in children with a compromised immune system should all be considered for treatment. Wounds with closure delayed more than 12 hours should also be considered high risk for infection. Treatment should be for 3 to 5 days with a penicillinase-resistant antibiotic such as a first generation cephalosporin or amoxicillin-clavulanic acid, with consideration to addition of metronidazole.25

Wound closure

The aim of wound closure is to reduce discomfort, aid healing and produce the best cosmetic result possible.26 The technique chosen for wound closure depends on the type of wound. Most wounds in children can be managed with primary closure, as the risk of infection is relatively low. Infected, heavily contaminated wounds and wounds resulting from high-energy projectiles are best managed by delayed primary closure, with initial cleansing and packing then closure 3 to 5 days later, once the risk of infection has decreased. Wounds with delayed presentation (>24 hours), or those contaminated with saliva or faeces should also be considered for delayed closure. Some wounds, such as puncture wounds or contaminated wounds in areas of poor perfusion should not be closed but allowed to heal by secondary intention. Once it is decided to close the wound, a technique that allows apposition of the wound edges that is secure and accurate and holds the wound edges in apposition until the strength of the wound is sufficient should be chosen. With improved technology the options for wound closure are growing. Those presently available include sutures, staples, tissue adhesives and tapes.

Sutures

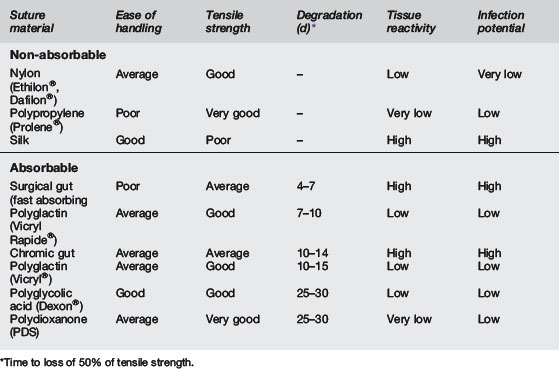

Suturing is the traditional method of wound closure. Sutures are divided into two classes on the basis of their degradation properties. Absorbable sutures degrade rapidly in vivo, and lose their tensile strength within 60 days. Sutures that degrade more slowly are classified as non-absorbable (Table 4.1.3 for individual suture material characteristics).

Non-absorbable sutures are made from either natural (silk, cotton, linen) or synthetic (nylon, Dacron®) fibres. They can also be classified according to their physical characteristics. Monofilament sutures are made from a single filament (nylon, Prolene®), and sutures containing multiple fibres are called multifilament (silk, cotton, nylon). Of these sutures, only nylon is available in both types of filament. Non-absorbable sutures are used to close fascial layers (where healing is slow) and for skin closure.27,28

Sutures come in varying sizes. The size of the suture to be used depends on the wound location and the tensile strength of the tissue to be sutured. Heavy sutures such as 4–0 should be used in the limbs and trunk, and should also be used on mucous membranes and subcutaneous tissue. Heaviest sutures such as 3–0 should be used on thick skin (such as the sole of the foot) or over large joints. Small sutures such as 6–0 should be used on tissues with light tensions, such as facial skin and subcutaneous tissue.27,28

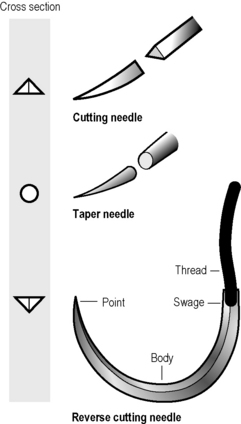

Needles

Needles come in varying sizes and shapes also. Needles are describes by the arc of curvature the needle possesses, and the shape of the needle itself. The most commonly used for skin closure is the 3/8 circle (135°) needle or the ½ circle (180°) needle (see Fig. 4.1.1). For closure of fascial layers ½ circumference needles are usually used. Needles that have two circumferences of curvature (compound needles) are able to be passed through the tissue with less rotation of the forearm. Needles come with different shapes as well as curvatures (see Fig. 4.1.1). A reverse cutting needle is the most common type used for skin closure. The needle cuts an inverted triangle and the suture sits on the base of the triangle, decreasing the likelihood of cutting out. A conventional cutting needle cuts a triangle into the skin and the suture sits in the apex of the triangle. For fascia a taper point needle is used. The cross-section of these needles is a circle that is tapered to a point. It does not cut but pushes the tissues aside, causing less tissue damage and reducing the chance of the stitch cutting out. For deep tissues that are stronger (such as tendon) a tapercut, or combination needle is used – it has a tapered body, but the point is a reverse cutting edge.28

Suturing techniques

For closure of a wound with sutures a number of instruments are needed to maintain a sterile field and to allow manipulation of the tissues and needle (Table 4.1.4). Finer instruments should be available for facial laceration repair.

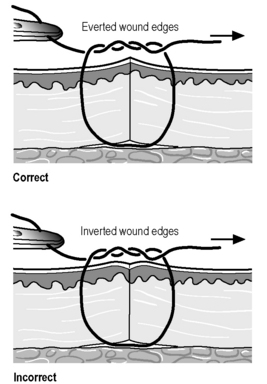

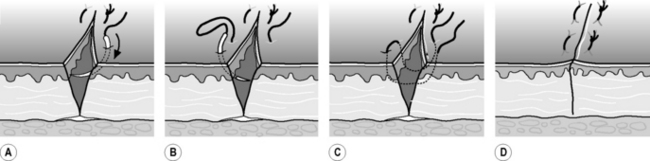

Sutures should be placed to allow apposition of all injured layers of the skin. Proper suture placement should result in slight eversion of the wound edges, avoiding a depression of the scar when contraction takes place during wound healing. To ensure eversion of skin edges the skin suture must be placed so that an equal amount of tissue is included on each side of the wound, and so that the needle bite includes a broad base (Figs 4.1.2 and 4.1.3). This is accomplished by lifting the wound edge as the needle is passed through the skin on each side, maximising the deep tissues included in the suture.28,29

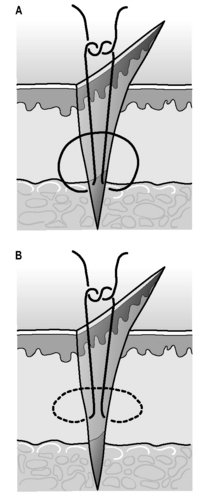

Most wounds sutured in the ED are closed with interrupted skin sutures. Synthetic non-absorbable sutures are most commonly used. However, rapidly absorbable sutures can be used to close the skin in children, avoiding the discomfort of suture removal. To place a simple interrupted suture the needle is held so the tip enters the skin at a right angle, and the hand rotated to ensure the needle remains at right angles to the skin throughout its passage, which aids in maximising the deep tissues captured in the bite. The stitch should be secured with an instrument tie and the knots secured to one side of the wound to minimise inflammation to the healing tissue. The initial throw should include two wraps of the suture material around the needle holder; subsequent throws should be wrapped once. The knot should be tied just tight enough to oppose the skin edges. Tying the knot too tightly will cause a reduction in the blood supply to the wound edges and increase the risk of infection and poor cosmetic outcome. Synthetic sutures with poor handling should have four or five throws per knot.28–30

There are generally two methods for closing a laceration, either suturing from one end to the other, or placing sutures that serially bisect the wound. A small linear wound is easily sutured from end to end, and long wounds without good landmarks on either side are most easily closed by placing the first stitch in the middle and then serially subdividing the wound. In wounds with definite landmarks, such as palmar skin creases or the vermillion border of the lip, the first suture should be placed to align these landmarks.28,30

Deep sutures should be placed where there are multiple layers of tissue involved and the skin sutures would be under tension. They are placed to reapproximate the dermal layers of the skin and remove skin tension, thus improving cosmetic outcome. Placing deep sutures inserts a foreign body into the wound and increases the risk of wound infection, so they should only be placed when necessary and the minimum number necessary used. For this reason, deep sutures should be avoided in the hands and feet. Deep sutures placed close to the skin are sometimes extruded through the wound. To place a deep suture, the needle is placed at the depth of the wound and removed at a more superficial level. The needle is then placed at the same superficial level on the opposite side of the wound and exits deeply so the knot is tied deeply in the wound (see Fig. 4.1.3).28,30

Special suturing techniques

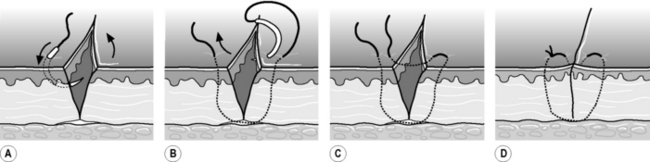

A variety of special suturing techniques are available with the sole purpose of aiding the provision of skin apposition with everted wound edges. The vertical mattress suture is useful in regions with minimal subcutaneous tissue where the edges are difficult to maintain in eversion. The technique is begun the same way as a simple skin suture, but after the suture loop is made, the skin is re-entered 1 to 2 mm from the wound edge and then tied (see Fig. 4.1.4). The horizontal mattress suture reinforces the subcutaneous tissue and relieves skin tension, but does not provide wound edge approximation as well as the vertical mattress suture (Fig. 4.1.5). The modified or half-buried horizontal mattress suture (or corner stitch) is the method of choice for closing a flap. It relieves tissue tension and avoids vascular compromise when approximating the tip of the flap (Fig. 4.1.6).28,30

Fig. 4.1.5 The horizontal mattress suture redistributes tension and everts wound edges.

(From an original drawing by Elaine Wheildon.)

A continuous suture can be used to close the laceration. It is faster to place than interrupted sutures, removal of sutures is easier and faster, and the tension is spread evenly along the wound. The continuous suture can be percutaneous or subcutaneous and made with absorbable or non-absorbable suture material. The disadvantages are that if one part of the suture breaks, the integrity of the whole wound is lost, and if the wound becomes infected, the whole wound needs to be opened to drain the pus. To place a percutaneous running stitch an interrupted suture is placed at one end of the wound and only the free end of the suture is cut. Suturing is continued along the wound in a coil pattern ensuring that the needle passes perpendicularly across the wound with each pass. The loop is tightened after each pass and the last stitch placed beyond the end of the laceration. The stitch is tied using the last loop as the tail.28,30

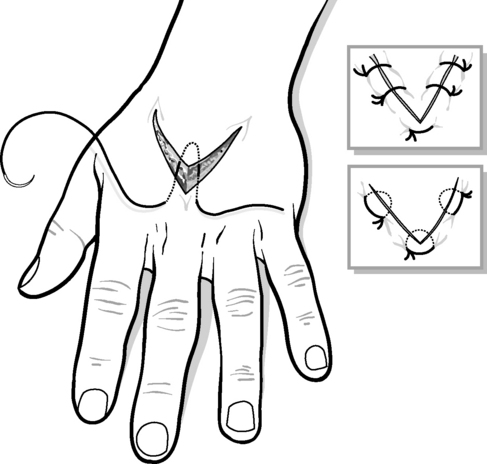

Correction of dog ears

A dog ear is the term given to a conical pucker of redundant skin that may develop at the ends of the wound during suturing. It is avoided by suturing the wound from the middle by sequentially bisecting the wound. Dog ears can be removed in many ways, the simplest of which is the overlap excision technique. The redundant skin is pulled across the wound from one side and excised along the line of the wound. Redundant skin from the opposite side is pulled across the wound and also excised along the line of the wound. The wound is then closed (Fig. 4.1.7).28

Staples

Stainless steel staples can be applied more rapidly than sutures, and they are associated with a lower rate of foreign body reaction and infection. Staples are generally considered especially useful for lacerations of the scalp, trunk, and limbs. However, they do not allow such meticulous wound apposition as sutures, and are slightly more painful to remove. They should not be used on the face or in any other wound where cosmetic outcome is a high priority.31

Tissue adhesives

The tissue glue is applied over the surface of the wound once its edges have been approximated by digital pressure. A number of thin layers of glue are applied across the wound and the wound held approximated for about 30 seconds. Care is taken not to allow glue to spill into eyes or orifices, and to avoid fixing forceps or gloves to the patient. The cyanoacrylates also act as their own dressing providing moist wound healing conditions under the glue, and have a degree of intrinsic antimicrobial activity. Careful attention to wound cleansing is still needed to avoid wound infections. In general, they are less expensive than sutures or staples and are strongly preferred by patients and families. A comparison of the various methods of wound closure is found in Table 4.1.5.32–34

Low tissue reactivity

Low cost

No risk of needle stick

Post-wound-closure care

Dressing and suture removal

After the wound has been sutured it should be covered with a non-adherent occlusive or semiocclusive dressing to protect the wound from bacterial invasion and provide a moist healing environment and speed wound healing. Ideally, the dressing is left intact until suture removal. The dressing should only be removed if it becomes saturated or there is a risk of infection and inspection is warranted. If the wound is not covered with a waterproof dressing the dressing can be removed every few days for showering. Non-absorbable sutures should be removed at the appropriate time, depending on the location of the injury. Removal of the sutures too early risks dehiscence; leaving sutures too long increases tissue reaction and the risk of cross-hatching and wound infection (Table 4.1.6). In general, sutures are removed earlier in children than in adults. Wounds closed with tissue adhesive should not be covered with an occlusive dressing, as the extra moisture will more rapidly decrease the ability of the glue to maintain wound edge apposition. The wound should be kept dry for 2–3 days, after which the patients may shower but should avoid bathing and swimming. Wounds closed with skin tapes should be kept dry to prevent premature removal.

Treatment of selected injuries

Eyelid lacerations

A thorough eye examination needs to be performed for all eyelid lacerations. Attention should be given to the possibility of a ruptured globe (eccentric pupil) or trauma to the globe (hyphaema, dislocated lens or retinal detachment). Visual acuity should be measured and documented. Any wound that penetrates the tarsal plate or the inner canthus requires specialist attention, as do wounds involving the lid margins. Any wound that cannot be adequately assessed (e.g. in a young child) should be referred for evaluation under anaesthesia.24

Superficial wounds of the eyelid are relatively easily repaired with 6–0 fast absorbing gut, with sutures placed close to the wound edge. Care must be taken not to suture into the tarsal plate or other deep structures.24

Lip lacerations

Wounds that involve the vermillion border (the junction of the dry oral mucosa and the facial skin) must be exactly realigned to achieve acceptable cosmetic results. A 6–0 suture should be used, with the first suture placed to exactly reappose the vermillion border.24 Further sutures should close the skin and the dry mucosal surface of the lip, with the wet mucosal surface only closed if it is gaping significantly.

Deep or through and through lacerations of the lip require deep sutures to repair the orbicularis oris muscle: if this is the case, an absorbable 6–0 suture should be used. The deep sutures should be placed after the initial suture is placed at the vermillion border and before tying that stitch.24

Tongue lacerations

The tongue should be maintained in position by a gentle pull using a towel clip or 4–0 suture placed through the tip. Interrupted 4–0 absorbable sutures should be placed using full thickness bites to include both mucosal surfaces and the lingual muscle in each stitch. Multiple knots should be used to secure the sutures and the parents warned that while the tongue is anaesthetised the child may bite through the stitch.24

Fingertip amputation

Injuries involving just the fingertip but not the nail heal very well. Injuries involving the nailbed or nail, but sparing bone, heal well. Those that involve the nailbed, nail and distal phalanx heal less well. Any injury with bone on view should be referred for specialist care.23,24,35

Nailbed lacerations

If the nail is lacerated, completely avulsed, or only loosely attached, the nail-bed must be explored. This can be done under local anaesthesia with a ring block of the digital nerves or under general anaesthesia. The nail must be removed and the nailbed repaired with 5–0 or 6–0 absorbable suture material. The space between the nailbed and nailfold must be packed with paraffin gauze or the nail replaced to prevent adhesions. If a fracture is present, antibiotics should be given. If the nail is partially avulsed only and is tightly adherent to the nailbed, it is reasonable to leave this intact as it will adequately splint and maintain apposition of any nailbed injury.24

Subungual haematoma

A subungual haematoma is a collection of blood between the nail and nailbed. It is most commonly seen with blunt fingertip injuries and may be associated with a fracture of the distal phalanx. Drainage of the haematoma usually provides symptomatic relief and should be undertaken whenever the haematoma is causing pain. Generally no local anaesthesia is required to drain the haematoma with cautery or needle burring using a 19-gauge needle. If there is an underlying fracture antibiotics should be administered. Nail removal for inspection of the nailbed should not be undertaken, regardless of the size of haematoma.24

Bites

Animal bites

Dog-bite injuries tend to be relatively large, relatively superficial crush injuries, which are seen most commonly on the face, neck and scalp in children. The overall infection rate for dog bites is about 10%, with facial wound infection rates of about 5%. Dog-bite wounds are infected with multiple organisms on all occasions, with both aerobic and anaerobic bacteria. It is reasonable to cleanse and close most dog bites, with antibiotic prophylaxis provided only to wounds that are high risk for infection (Tables 4.1.7 and 4.1.8). Amoxicillin with clavulanate is the most useful drug.

Cat bites, on the other hand, are typically puncture wounds with less surrounding tissue injury. They have bacteria inoculated deep into the wound, which is difficult to explore, irrigate or debride. The risk of infection is significantly higher than in dog bite – at least twice as likely – because of the puncture-type wound, the most common location of the bite being the hand, and the high incidence (about 80%) of Pasteurella multocida found in cats’ mouths. P. multocida is a facultative, anaerobic Gram-negative rod that often results in rapidly progressive cellulitis. It is sensitive to the penicillins and variably sensitive to macrolides and first-generation cephalosporins. All these drugs have been documented as adequately treating infections of P. multocida, but treatment failures have been documented for erythromycin and first-generation cephalosporins. It is recommended that all cat bites receive prophylactic antibiotics (see Table 4.1.7).36,37

Human bites

Most human bites are probably at no more risk of infection than ordinary lacerations and they are not considered to carry a high risk of human immunodeficiency virus transmission. Prophylactic antibiotics have, however, been shown to reduce the risk of infection. Appropriate prophylactic antimicrobial choices for human bite injuries include amoxicillin with clavulanate.36 However, the clenched-fist injury (or fight bite), which commonly causes a ragged laceration over the fourth or fifth metacarpophalangeal joint is at high risk of infection. These latter wounds should all receive prophylactic antibiotics, as should human bites (including self-inflicted bites) that have high-risk properties (see Tables 4.1.7 and 4.1.8).36

Subcutaneous sutures close deep wound dead space reducing fluid collection and infection, but deep sutures of themselves can cause infection by acting as a foreign body.

Subcutaneous sutures close deep wound dead space reducing fluid collection and infection, but deep sutures of themselves can cause infection by acting as a foreign body. Dressing practice for all wounds is changing to promote moist wound healing; this speeds rate of healing and improves wound comfort.

Dressing practice for all wounds is changing to promote moist wound healing; this speeds rate of healing and improves wound comfort. A number of topical anaesthetic creams are being used in extremity wounds despite not being licensed for this use.

A number of topical anaesthetic creams are being used in extremity wounds despite not being licensed for this use.1 Singer A.J., Thode H.C.Jr, Hollander J.E. National trends in ED lacerations between 1992 and 2002. Am J Emerg Med. 2006;24(2):183-188.

2 Young S.J., Barnett P.L., Oakley E.A. 10. Bruising, abrasions and lacerations: minor injuries in children I. Med J Aust. 2005;182(11):588-592.

3 Hollander J.E., Singer A.J. Laceration management. Ann Emerg Med. 1999;34:356-367.

4 Capellan O., Hollander J.E. Management of lacerations in the emergency department. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2003;21:205-231.

5 Hollander J.E., Singer A.J., Valentine S.M., Shofer F.S. Risk factors for infection in patients with traumatic lacerations. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:716-720.

6 Knapp J.F. Updates in wound management for the paediatrician. Pediatr Clin North Am. 1999;46:1201-1213.

7 NHMRC. The Australian Immunisation Handbook, 8th ed. Commonwealth of Australia; 2008.

8 Singer A.J., Hollander J.E., Quinn J. Evaluation and management of traumatic lacerations. N Engl J Med. 1997;337:1142-1148.

9 Baruch J. Laceration repair. J Gen Intern Med. 2005;20(6):556-558.

10 Weinberger L.N., Chen E.H., Mills A.M. Is screening radiography necessary to detect retained foreign bodies in adequately explored superficial glass-caused wounds? Ann Emerg Med. 2008;51(5):666-667.

11 Anderson M.A., Newmeyer W.L., Kilgore E.S.J. Diagnosis and treatment of retained foreign body in the hand. Am J Surg. 1982;114:63.

12 Zempsky W.T., Karasic R.B. EMLA versus TAC for topical anesthesia of extremity wounds in children. Ann Emerg Med. 1997;30:163-166.

13 Kennedy R.M., Luhmann J.D. Pharmacological management of pain and anxiety during emergency procedures in children. Paediatr Drugs. 2001;3(5):337-354.

14 Ernst A.A., Marvez-Vails E., Nick T.G., et al. LAT versus TAC for topical anesthesia in face and scalp lacerations. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:151-154.

15 Blackburn P.A., Butler K.H., Hughes M.J., et al. Comparison of tetracaine–adrenaline–cocaine (TAC) with topical lidocaine–adrenaline (TLE): Efficacy and cost. Am J Emerg Med. 1995;13:315-317.

16 Loryman B., Davies F., Chavada G., Coats T. Consigning “brutacaine” to history: a survey of pharmacological techniques to facilitate painful procedures in children in emergency departments in the UK. [see comment]. Emerg Med J. 2006;23(11):838-840.

17 Priestley S., Kelly A.M., Chow L., et al. Application of topical local anesthetic at triage reduces treatment time for children with lacerations: a randomized controlled trial.[see comment]. Ann Emerg Med. 2003;42(1):34-40.

18 Sectish T.C. Use of sedation and local anesthesia to prepare children for procedures. Am Fam Physician. 1997;55:909-916.

19 Seropian R., Reynolds B. Wound infection after preoperative depilatory versus razor preparation. Am J Surg. 1971;121:251.

20 Moscati R.M., Mayrose J., Reardon R.F., Janicke D.M., Jehle D.V. A multicenter comparison of tap water versus sterile saline for wound irrigation.[see comment]. Acad Emerg Med. 2007;14(5):404-409.

21 Stevenson T.R., Thacker J.G., Rodeheaver G.T., et al. Cleansing the traumatic wound by high pressure syringe irrigation. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians. 1976;5:17-21.

22 Wheeler C.B., Rodeheaver G.T., Thacker J.G., et al. Side effects of high pressure irrigation. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1976;143:775-778.

23 Al-Nammari S.S., Quyn A.J. Towards evidence based emergency medicine: best BETs from the Manchester Royal Infirmary. Conservative management or suturing for small, uncomplicated hand wounds. Emerg Med J. 2007;24(3):217-218.

24 Brown D.J., Jaffe J.E., Henson J.K. Advanced laceration management. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2007;25(1):83-99.

25 . Post traumatic wound infections. eTG complete (Internet). Melbourne: Therapeutic Guidelines Ltd. 2009. http://online.tg.org.au/ip/. [accessed 10.12.09]

26 Singer A.J., Mach C., Thode H.C.J., et al. Patient priorities with traumatic lacerations. Am J Emerg Med. 2000;18:683-686.

27 Lin K., Farinholt H., Reddy V., et al. The scientific basis for selecting surgical sutures. J Long Term Eff Med Implants. 2001;11:29-40.

28 Ratner D., Nelson B.R., Johnson T.M. Basic suture materials and suturing techniques. Semin Dermatol. 1994;13:20-26.

29 . Sutures and Needles. eMedicine. 2009. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/884838-overview. [accessed 15.11.09]

30 . Suturing Techniques. eMedicine. 2009. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1128240-overview. [accessed 16.11.09]

31 Khan A., Dayan P.S., Miller S., et al. Cosmetic outcome of scalp wound closure with staples in the pediatric emergency department: a prospective randomised trial. Pediatr Emerg Care. 2002;18:171-173.

32 Holger J.S., Wandersee S.C., Hale D.B. Cosmetic outcomes of facial lacerations repaired with tissue-adhesive, absorbable, and nonabsorbable sutures. Am J Emerg Med. 2004;22(4):254-257.

33 Farion K.J., Osmond M.H., Hartling L., et al. Tissue adhesives for traumatic lacerations: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Acad Emerg Med. 2003;10(2):110-118.

34 Singer A.J., Thode H.C.Jr. A review of the literature on octylcyanoacrylate tissue adhesive. Am J Surg. 2004;187(2):238-248.

35 Quinn J., Cummings S., Callaham M., Sellers K. Suturing versus conservative management of lacerations of the hand: randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2002;325:299-305.

36 Broom J., Woods M. Management of bite injuries. Australian Prescriber. 2006;29:6-8.

37 . Bites, Animal: Treatment & Medication. eMedicine. 2009. http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/768875-overview. [accessed 15.11.09]