Wound care

Wounds

The wound healing process is like a symphony, requiring many integral components to work together toward a common goal—healing a wound.

The wound healing process is like a symphony, requiring many integral components to work together toward a common goal—healing a wound.

Normal wound healing begins with the initial platelet plug in the inflammatory phase, to a proliferative collagen-producing phase and an ultimate remodeling phase, which can last up to 1 year. Platelets, neutrophils, macrophages, and fibroblasts interact via multiple cytokines and cell signaling pathways to coordinate the transition from one phase to another.

Normal wound healing begins with the initial platelet plug in the inflammatory phase, to a proliferative collagen-producing phase and an ultimate remodeling phase, which can last up to 1 year. Platelets, neutrophils, macrophages, and fibroblasts interact via multiple cytokines and cell signaling pathways to coordinate the transition from one phase to another.

The arrest of a wound in one of those states, as well as prevention of progress to the next phase, may result in a nonhealing wound. As part of a surgical team, it is helpful to recognize potential challenges to normal wound healing and prepare patients for delayed wound healing or refer them promptly when indicated.

The arrest of a wound in one of those states, as well as prevention of progress to the next phase, may result in a nonhealing wound. As part of a surgical team, it is helpful to recognize potential challenges to normal wound healing and prepare patients for delayed wound healing or refer them promptly when indicated.

History

Identify any comorbid medical conditions or medications that could delay normal wound healing:

Identify any comorbid medical conditions or medications that could delay normal wound healing:

Obtain a history of taking anticoagulants (aspirin, clopidogrel, coumadin) and the reason for taking them.

Obtain a history of taking anticoagulants (aspirin, clopidogrel, coumadin) and the reason for taking them.

Physical examination

Inspect the Wound for Injury to Neurovascular or Tendinous Structures

Inspect the Wound for Injury to Neurovascular or Tendinous Structures

Inspect the Wound for Hemostasis, Exposed Bone, or Hardware if Postsurgical

Inspect the Wound for Hemostasis, Exposed Bone, or Hardware if Postsurgical

Acute wounds

Inspect the wound for the degree of contamination (e.g., road rash, grass, dirt).

Inspect the wound for the degree of contamination (e.g., road rash, grass, dirt).

Determine if there is actual tissue loss versus the appearance of a “gaping wound” because the wound margins are pulled in opposite directions.

Determine if there is actual tissue loss versus the appearance of a “gaping wound” because the wound margins are pulled in opposite directions.

• This helps distinguish wounds with sharply cut margins that can be reapproximated from ones with skin and soft tissue loss that can be treated with local wound care acutely.

Determine if there is a skin avulsion or a flap of skin detached from underlying structures but attached to intact skin along one margin.

Determine if there is a skin avulsion or a flap of skin detached from underlying structures but attached to intact skin along one margin.

Chronic wounds

Is the wound clean or does it have necrotic debris? Is there evidence of infection?

Is the wound clean or does it have necrotic debris? Is there evidence of infection?

Is the patient sensate in the anatomic location of the wound (i.e., plantar ulcer with lack of plantar sensation)?

Is the patient sensate in the anatomic location of the wound (i.e., plantar ulcer with lack of plantar sensation)?

Does the patient have palpable pulses in the extremity with the wound?

Does the patient have palpable pulses in the extremity with the wound?

Is there exposed bone (or tendon)? If so, osteomyelitis must be considered.

Is there exposed bone (or tendon)? If so, osteomyelitis must be considered.

Principles of wound care: Treatment

Irrigation and débridement

1) Irrigate the wound with sterile normal saline with a device producing 7 to 15 pounds per square inch (psi) of pressure. Examples include commercially available pulse lavage devices and a 30-mL syringe attached to an 18-gauge angiocatheter.

2) Débride the wound of any contaminants such as grass and gravel. Minimize actual excision of tissue in the acute setting, and only débride obviously nonviable tissues.

Closure

To minimize scarring, close acute wounds on extremities (excluding the hand and fingers) in layers.

To minimize scarring, close acute wounds on extremities (excluding the hand and fingers) in layers.

• Use monofilament suture for contaminated wounds to minimize bacterial seeding of braided suture (see later section on Sutures).

• Avoid tension-creating techniques (vertical and horizontal mattress suture repair) because these are more likely to cause necrosis of the skin edges.

• Approximate muscle with strong absorbable monofilament suture that will last around 90 days (e.g., PDS suture).

• Approximate dermis with absorbable monofilament suture that will last around 40 days (e.g., Monocryl).

• Approximate skin with permanent monofilament suture that will be removed in 1 to 2 weeks (e.g., Prolene, Nylon).

• Wounds on the hand, fingers, and plantar foot should be closed in one layer only, with permanent monofilament suture taking bites through the epidermis and dermis.

Chronic wounds

Treatment is based on the etiology of the chronicity of the wound. Identify (on the basis of the history) the main etiology for the delayed wound healing.

Treatment is based on the etiology of the chronicity of the wound. Identify (on the basis of the history) the main etiology for the delayed wound healing.

• Treat contaminated wounds with mechanical débridement in the office or enzymatic débridement or dressings that will débride the wound (normal saline wet-to-dry dressing changes twice daily). Chemicals such as Dakin solution should not be used for more than 48 hours because they can be toxic to healthy tissues.

• Treat pressure ulcers with appropriate orthotics for pressure offloading or total contact casts if the patient is a candidate.

• Treat arterial ulcers with referrals to vascular surgery for evaluation of inflow.

• Treat diabetic ulcers with education (inspecting footwear and regular extremity examinations) and adequate glucose control.

• Treat venous ulcers with graduated compression and edema control with an Unna boot, compression stockings, and elevation.

• Infected wounds need operative débridement and appropriate antibiotic therapy.

Many commercially available products are available for wound care, which is as much an art as it is a science. Fundamentally the provider must determine if the wound needs débridement or if it needs a moist environment with adjuncts to allow proper healing.

Many commercially available products are available for wound care, which is as much an art as it is a science. Fundamentally the provider must determine if the wound needs débridement or if it needs a moist environment with adjuncts to allow proper healing.

• The ideal wound healing environment is slightly moist to encourage epithelialization. Topical antimicrobials (e.g., polysporin, bacitracin) or hydrogels are helpful when applied with a gauze dressing changed once a day.

• More frequent dressing changes are helpful when trying to débride the wound with dressing changes (as in normal saline wet-to-dry dressing changes).

• Refer your patient to a dedicated wound care specialist if you are not seeing improvement in the wound.

Negative pressure therapy for wounds

Wound vac therapy effectively decreases wound surface area and increases blood flow to promote healing in clean wounds.

Wound vac therapy effectively decreases wound surface area and increases blood flow to promote healing in clean wounds.

Wounds should be clean, without exposed vital structures, before placement of this dressing. Often this is best accomplished in the operating room, and the dressing is then changed every other day.

Wounds should be clean, without exposed vital structures, before placement of this dressing. Often this is best accomplished in the operating room, and the dressing is then changed every other day.

Sutures

Needle

Commonly used permanent suture

Prolene

Both Nylon and Prolene have similar applications: skin closure and tendon repairs. It is often a matter of personal preference as to the choice of one over another.

Both Nylon and Prolene have similar applications: skin closure and tendon repairs. It is often a matter of personal preference as to the choice of one over another.

Permanent skin suture should be removed as soon as the wound is ready to prevent unsightly cross-hatched scars (7 to 14 days depending on the patient and anatomic site).

Permanent skin suture should be removed as soon as the wound is ready to prevent unsightly cross-hatched scars (7 to 14 days depending on the patient and anatomic site).

Suture technique

1) Always enter the skin with the needle perpendicular to the skin.

2) The distance from the entry of the needle to the wound on one side of the wound should equal the distance of the needle entry to exit on the other side of the wound.

3) The depth of the needle penetration should be equivalent on both sides of the wound to prevent the creation of a shelf, or mismatched wound margins.

4) Maximize eversion of the wound margins to facilitate optimal appearance of the ultimate scar.

Strength layers include dermis and fascia. Sutures in subcutaneous fat will not hold tension and will not minimize scarring, but careful placement of buried approximating sutures in the fascia and dermis will result in finer scars.

Strength layers include dermis and fascia. Sutures in subcutaneous fat will not hold tension and will not minimize scarring, but careful placement of buried approximating sutures in the fascia and dermis will result in finer scars.

Regardless of the technique, if percutaneous sutures remain in place for too long, they will result in a scar with crosshatching or have a so-called “railroad track” appearance. Prevent this with timely removal of sutures. Placement of a deep, buried layer of dermal approximating suture allows expedient removal of percutaneous epidermal sutures.

Regardless of the technique, if percutaneous sutures remain in place for too long, they will result in a scar with crosshatching or have a so-called “railroad track” appearance. Prevent this with timely removal of sutures. Placement of a deep, buried layer of dermal approximating suture allows expedient removal of percutaneous epidermal sutures.

Practice atraumatic tissue handling (e.g., avoid pinching skin with forceps) to optimize the appearance of the scar and minimize damage to tissues being repaired.

Practice atraumatic tissue handling (e.g., avoid pinching skin with forceps) to optimize the appearance of the scar and minimize damage to tissues being repaired.

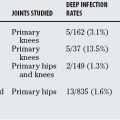

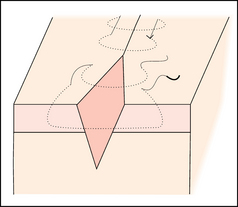

Simple interrupted: Figure 12-1

Figure 12-1. Simple interrupted suture.

Technique: With wrist pronated, enter the skin with the needle perpendicular to the skin and wound. Then supinate and travel across the wound, taking equal bites on either side of the wound edge, and grasp the needle. When viewed in cross section the bite should look like a pear, wider in the dermis and narrower in the epidermis to optimize the final appearance of the scar. The knot is secured after the needle passes through both sides of the wound.

Technique: With wrist pronated, enter the skin with the needle perpendicular to the skin and wound. Then supinate and travel across the wound, taking equal bites on either side of the wound edge, and grasp the needle. When viewed in cross section the bite should look like a pear, wider in the dermis and narrower in the epidermis to optimize the final appearance of the scar. The knot is secured after the needle passes through both sides of the wound.

Simple running: Figure 12-2

Figure 12-2. Simple running suture.

Technique: See earlier description for a simple interrupted suture. The difference is that after the first bite, the needle is left attached to the suture end and continuously used from one wound margin to the other with a knot secured at the beginning and one secured at the end of the area to be approximated.

Technique: See earlier description for a simple interrupted suture. The difference is that after the first bite, the needle is left attached to the suture end and continuously used from one wound margin to the other with a knot secured at the beginning and one secured at the end of the area to be approximated.

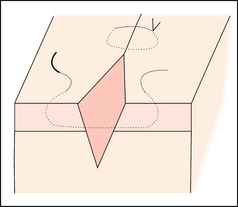

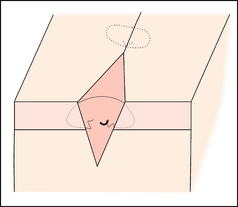

Vertical mattress: Figure 12-3

Figure 12-3. Vertical mattress suture.

Technique: Also called “far-far-near-near stitch.” See earlier description for a simple interrupted suture. After taking the first bite in the deeper layer, the needle is reversed and the “near-near” bite is taken. This is a smaller bite (both in depth and distance to the wound), taken in the opposite direction as the first bite. The knot is secured on the side of the wound. The knot should be secured away from any potentially compromised tissue (e.g., the knot is not secured on the same side as a flap of skin).

Technique: Also called “far-far-near-near stitch.” See earlier description for a simple interrupted suture. After taking the first bite in the deeper layer, the needle is reversed and the “near-near” bite is taken. This is a smaller bite (both in depth and distance to the wound), taken in the opposite direction as the first bite. The knot is secured on the side of the wound. The knot should be secured away from any potentially compromised tissue (e.g., the knot is not secured on the same side as a flap of skin).

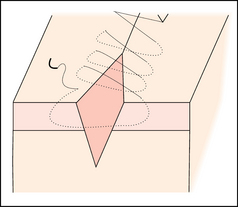

Horizontal mattress: Figure 12-4

Figure 12-4. Horizontal mattress suture.

Technique: See earlier technique for a simple interrupted suture. Before tying the knot, the needle is brought back in the reverse direction across the wound. The second entry point is made after traveling parallel to the wound the same distance as the previous exit point was from the wound edge. The needle is then passed as a simple interrupted suture in the reverse direction and secured on the side of the wound. The knot should be secured away from any potentially compromised tissue (e.g., the knot is not secured on the same side as a flap of skin).

Technique: See earlier technique for a simple interrupted suture. Before tying the knot, the needle is brought back in the reverse direction across the wound. The second entry point is made after traveling parallel to the wound the same distance as the previous exit point was from the wound edge. The needle is then passed as a simple interrupted suture in the reverse direction and secured on the side of the wound. The knot should be secured away from any potentially compromised tissue (e.g., the knot is not secured on the same side as a flap of skin).

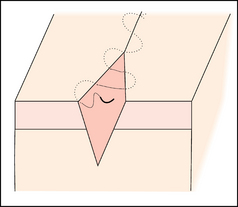

Buried deep dermal: Figure 12-5

Figure 12-5. Deep dermal buried suture.

Technique: Enter the wound from a deep aspect, not the epidermis. With the needle perpendicular to the dermis, the dermis is entered and the wrist is supinated. The needle should exit just deep to the dermal-epidermal junction and travel across the wound. Enter the other side of the wound at the same level as the exit on the opposite side (just below the dermal-epidermal junction). Supinate and then exit in the deep dermis across from the entry point on the other side. The knot is secured deep in the wound, and the tails of the knot are cut flush with the knot.

Technique: Enter the wound from a deep aspect, not the epidermis. With the needle perpendicular to the dermis, the dermis is entered and the wrist is supinated. The needle should exit just deep to the dermal-epidermal junction and travel across the wound. Enter the other side of the wound at the same level as the exit on the opposite side (just below the dermal-epidermal junction). Supinate and then exit in the deep dermis across from the entry point on the other side. The knot is secured deep in the wound, and the tails of the knot are cut flush with the knot.

Subcuticular: Figure 12-6

Figure 12-6. Subcuticular suture.

Technique: A buried deep dermal stitch is secured deep in the wound at the apex. Then the needle is passed from deep to superficial at the wound apex, and horizontal bites are taken (in contrast to all the previous bites described in this chapter). The bite is taken at the dermal-epidermal junction. The needle enters perpendicular to the dermis with the needle held parallel to the epidermal surface. The needle then enters the contralateral edge of the wound at the same vertical depth and longitudinal wound distance or mirror image of where it exited on the previous wound margin. This is repeated until closure of the wound, and a buried knot is secured at the end with the tails of the knot cut flush with the knot.

Technique: A buried deep dermal stitch is secured deep in the wound at the apex. Then the needle is passed from deep to superficial at the wound apex, and horizontal bites are taken (in contrast to all the previous bites described in this chapter). The bite is taken at the dermal-epidermal junction. The needle enters perpendicular to the dermis with the needle held parallel to the epidermal surface. The needle then enters the contralateral edge of the wound at the same vertical depth and longitudinal wound distance or mirror image of where it exited on the previous wound margin. This is repeated until closure of the wound, and a buried knot is secured at the end with the tails of the knot cut flush with the knot.

Ethicon. Knot tying manual. Somerville: Ethicon; 2005.

Ethicon. Wound closure manual. Somerville: Ethicon; 2005.

Vasconez HC, Habash A, Plastic and reconstructive surgery, Doherty GM, ed. CURRENT diagnosis & treatment, surgery, ed 13. New York, McGraw-Hill, 2010.

Weitzul S, Taylor RS. Suturing technique and other closure materials. In Robinson JK, ed.: Surgery of the skin, ed 2, Saint Louis: Elsevier, 2010.