Chapter 84 Wilms’ Tumor

PATHOPHYSIOLOGY

Wilms’ is typically a large, encapsulated, single tumor arising from the renoblast cells located in the renal parenchyma. A membranous capsule usually encloses the tumor. Wilms’ tumors may be multifocal, extend to surrounding structures, involve both kidneys, cause obstruction of the inferior vena cava, invade local retroperitoneal lymph nodes, and/or obstruct the intestines. Metastasis most often occurs in the lungs, followed by the liver and the contralateral kidney, and in rare cases spreads to the bone. Ten percent of Wilms’ patients have associated congenital anomalies such as WAGR syndrome (Wilms’, aniridia—absence of pupils, genitourinary [GU] abnormalities, and mental retardation) hypospadias, cryptorchidism, Denys-Drash syndrome (pseudohermaphroditism, GU ambiguity), cardiac malformations, and aniridia. Another 10% have phenotypic or overgrowth syndromes (syndromes characterized by overgrowth of organs or features) such as hemihypertrophy, and Simpson-Golabi-Behmel and Beckwith-Wiedemann. Children with overgrowth syndromes should be screened for Wilms’ using renal ultrasound every 3 months until they are 10 years of age.

Wilms’ tumor grows rapidly, and typically it is very large when detected. Tissue type varies from “favorable” to “unfavorable” and is the most significant prognostic characteristic. Children with favorable histologic characteristics have 95% survival. Within this favorable category is a cystic, partially differentiated nephroblastoma variant that has 100% survival with surgery alone. Unfavorable histologic characteristics include various degrees of anaplasia (e.g., enlarged nucleus; hyperploidy, which increases the potential for metastasis) that account for more aggressive disease and are more common in children over 2 years of age. The more areas of anaplasia seen, the more aggressive the tumor. Clear-cell sarcoma and rhabdoid tumors are aggressive renal tumors and are not classified as Wilms’ tumor. Congenital mesoblastic nephromas are benign renal tumors that are also not considered in the Wilms’ family of tumors. Nephroblastomatosis is a focus of cells that, if found, indicate a precursor lesion with a higher risk of development of tumor in the contralateral kidney. These are resting cells, also known as “nephrogenic rests,” with a propensity to become Wilms’.

A small percentage of Wilms’ tumors are hereditary. Hereditary forms account for the majority of bilateral Wilms’. Chromosomal abnormalities linked to specific genes such as WT1 and WT2 are now known to be associated with the predisposition to Wilms’ tumor. WT1 gene has been found on short arm of chromosome 11p13. WT2 has been mapped to 11p15 location and is associated with Beckwith-Weidemann syndrome. These genetic mutations can occur sporadically or be inherited.

INCIDENCE

1. Wilms’ tumor accounts for 6% of childhood cancers and 8% of all solid tumors in children. It is the most common renal malignancy in children. There are 500 children diagnosed annually in the United States.

2. Age range of peak incidence is 2 to 3 years; it is rarely seen after age 6.

3. Of Wilms’ tumors, 5% are bilateral, affecting both kidneys, and 1% to 2% are familial.

4. Prognosis varies according to the stage of the disease at the time of diagnosis and histologic characteristics of the tumor cells.

5. Overall survival rate of children with Wilms’ tumors is 90%.

CLINICAL MANIFESTATIONS

The first three of the following symptoms are the predominant clinical manifestations.

COMPLICATIONS

1. Metastasis to lungs, liver, contralateral kidney, bone marrow

2. Hepatic: local tumor extension resulting in lymphatic blockage and causing ascites

3. Cardiovascular: local tumor extension causing vena cava clots

4. Gastrointestinal: bowel obstruction from tumor, ileus, adhesions

5. Renal: renal dysfunction or failure; hypertension

6. Short- and long-term adverse reactions to chemotherapy and/or radiation therapy

LABORATORY AND DIAGNOSTIC TESTS

1. Computed tomography (CT), ultrasonography, and/or magnetic resonance imaging of the kidneys—to detect mass, tumor thrombus in renal veins, enlarged lymph nodes, and tumor relationship to adjoining structures

2. Liver function tests (alanine transaminase [ALT], aspartate transaminase [AST], total and direct bilirubin)—to detect liver involvement

3. Complete blood count (CBC)—to assess anemia and possible bone marrow involvement

4. Urinalysis—to assess for hematuria

5. Urinary catecholamine levels—tumor markers used to rule out neuroblastoma

6. Blood urea nitrogen, creatinine, and electrolyte levels—to assess renal function

7. Chest CT scan or chest x-ray study—to assess for metastasis

8. Additional testing of liver, bone, and brain only if additional symptoms indicate involvement

MEDICAL AND SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

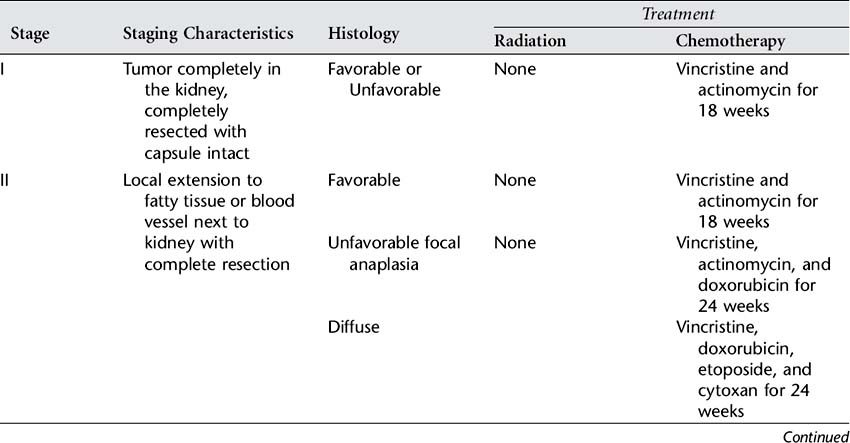

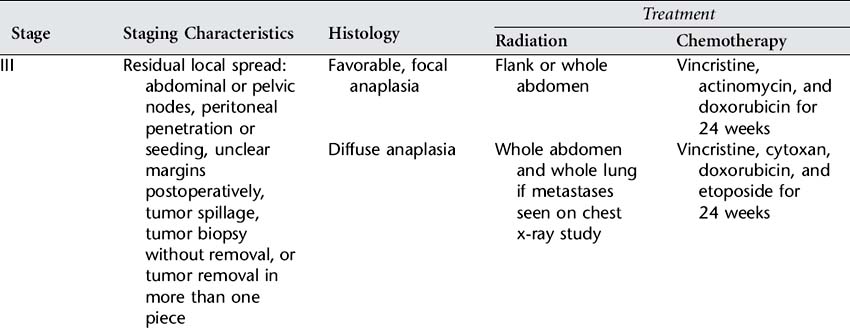

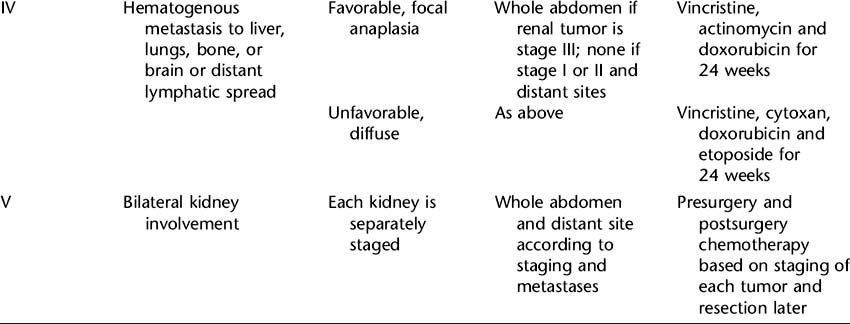

Skillful surgery is essential for successful treatment of Wilms’ tumor. A nephrectomy, or removal of the affected kidney, is performed to remove the tumor and to provide tissue for diagnosis, histologic examination, and staging. It also provides an opportunity to explore and biopsy lymph nodes and abdominal organs for involvement. Surgery allows staging, which is the exact determination of the extent of the disease at the time of diagnosis. The National Wilms’ Tumor Study (NWTS) group staging system consists of five stages that reflect the extent of disease. Exact staging is essential to determine the appropriate further treatment, which will include chemotherapy with or without radiation therapy. See Table 84-1 for the NWTS-5 summary of staging and recommended treatment. Bilateral tumors require separate staging, and since resection of both kidneys is not feasible, a second surgery after chemotherapy is required to examine the potential for resection of remaining disease.

Wilms’ tumor is radiosensitive. The decision to use radiation therapy is based on the histologic features and stage of the tumor and the success of surgery. Radiation doses delivered to the flank of the affected kidney are now given evenly over the vertebrae to eliminate the risk of scoliosis. The chemotherapy drugs and dosage chosen are highly individualized and are also based on extent of disease, histologic features, and the degree of surgical success. The following drugs may be given: vincristine, actinomycin D, doxorubicin, cyclophosphamide, etoposide, and ifosfamide. Use of single-, intensive-dose and shortened-interval chemotherapy rather than longer-duration chemotherapy has been found to improve cure rates and decrease toxicity. Dosing of doxorubicin and dactinomycin are decreased during radiation to limit side effects.

NURSING ASSESSMENT

1. See Renal Assessment section in Appendix A (acites, urine output assessment).

2. Assess preoperatively for enlarged abdomen in flank areas (do not palpate tumor).

3. Assess for bowel sounds and abdominal distention postoperatively.

4. Assess for preoperative and postoperative pain (see Appendix I).

5. Assess wound for drainage and signs of infection.

6. Assess for complications of all aspects of treatment including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiation therapy.

7. Assess child’s and family’s responses to illness and surgery.

8. Assess child’s developmental level (see Appendix B).

9. Assess knowledge and learning needs of family and caregivers.

NURSING DIAGNOSES

NURSING INTERVENTIONS

Preoperative Phase

1. Avoid palpation of abdomen to prevent seeding of tumor.

2. Monitor child’s clinical status; observe for signs and symptoms of complications (refer to Complications section in this chapter).

3. Provide age-appropriate preprocedural and presurgical explanations to child to alleviate anxiety (see Preparation for Procedures or Surgery section in Appendix F).

4. Encourage child and parents to express concerns, questions, and fears about diagnosis (see the Supportive Care section in Appendix F).

Postoperative Care

1. Monitor child’s clinical status.

2. Monitor child’s abdominal functioning.

3. Promote fluid and electrolyte balance.

Chemotherapy and Radiation Phase

1. Provide for child’s hygienic needs.

2. Protect child from infection resulting from immunosuppression. Educate family about symptoms to report.

3. Monitor side effects of radiotherapy; tumor is remarkably sensitive to radiation.

4. Monitor and minimize side effects of chemotherapy. Provide anticipatory guidance for family regarding treatment-related side effects and preventive and management measures. The following are a few side effects that necessitate specific teaching or specific interventions. The list is not inclusive. All can contribute to anorexia and weight loss (refer to Table 49-1 in Leukemia chapter for additional information).

5. Maintain aseptic care of intravenous access device (IVAD).

6. Maintain adequate nutritional status.

7. Monitor and alleviate child’s pain (see Appendix I).

8. Provide education about symptoms of anemia and thrombocytopenia and the risks and benefits of transfusions when needed.

9. Forewarn parents and youth that fatigue from therapy can worsen neuropathy from vincristine secondary to disuse.

10. Provide developmentally appropriate stimulation and/or activities for child (see Appendix B).

Discharge Planning and Home Care

1. Instruct parents about various aspects of medical management.

2. Provide information to parents about available resources.

3. Provide emotional support and referral to support groups for parents, siblings, and affected child (refer to Appendix F).

4. Encourage normal parenting and discipline. Facilitate ongoing school performance.

5. Instruct parents to monitor and be aware of long-term effects.

CLIENT OUTCOMES

1. Child will be free of complications and learn to recognize possible side effects and how to prevent and deal with them appropriately.

2. Child’s level of anxiety before procedures and surgery will be minimized.

3. Child and family will adhere to long-term treatment regimen.

4. Child’s development will be physically, socially, and emotionally typical for age.

5. The family will remain intact and adapt the diagnosis and its management into their routines.

Dome JS, et al. Wilms’ tumor. Pizzo PA, Poplack DG. Principles and practice of pediatric oncology, ed 5, Philadelphia: Lippincott, Williams & Wilkins, 2006.

Drigan R, Androkites AL. Wilms’ tumor. Baggott CR, et al. Nursing care of children and adolescents with cancer, ed 3, Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 2002.

Duffy-Lind E. Tumors of the kidney. Kline NE, ed. Essentials of pediatric oncology nursing: A core curriculum, ed 2, Glenview, IL: Association of Pediatric Oncology Nurses, 2004.

National Childhood Cancer Foundation Children’s/Oncology Group. Wilms’ Tumor. [(serial online)] .CureSearch, 2006. www.curesearch.org/for_parents_and_families/newlydiagnosed/article.aspx?ArticleId=3226&StageID=1&TopicId=1&Level=1. Accessed March 9

U.S. National Institutes of Health. Wilms’ tumor and other childhood kidney tumors (PDQ): Treatment. [(serial online)] .National Cancer Institute, 2006. www.cancer.gov/cancertopics/pdq/treatment/wilms/healthprofessional/. Accessed March 9