CHAPTER 33 Wilms Tumor

Step 1: Surgical Anatomy

Normal Anatomy

Anatomic Variations

Step 2: Preoperative Considerations

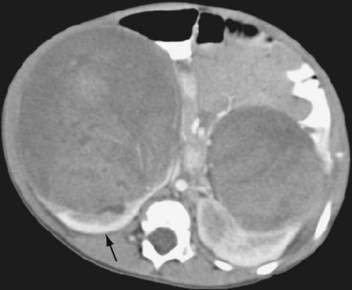

Imaging

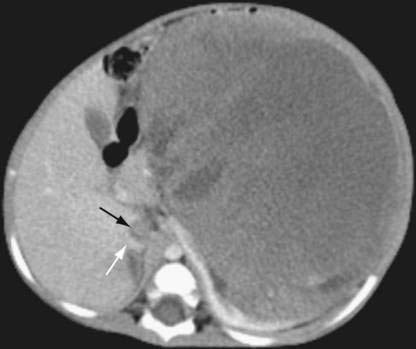

Assessment of the Primary Tumor

Assessment of Vascular Extension

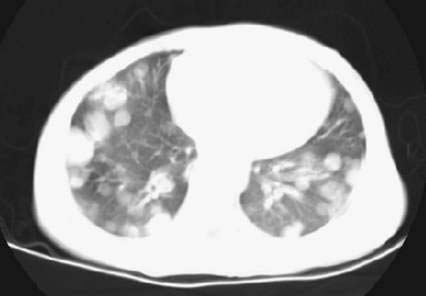

Assessment of Metastatic Disease

Associated Medical Conditions

Renal Function

Pulmonary Function

Hypertension

Predisposition Syndrome

| NAME | GENETIC ABNORMALITY | ASSOCIATED ANOMALIES |

|---|---|---|

| WAGR syndrome | 11p13 (WTI) deletion | Aniridia, Genitourinary anomalies, mental Retardation |

| Denys-Drash syndrome | WTI mutation | Nephropathy, intersex disorders |

| Beckwith-Wiedemann syndrome | 11p15 (WT2) abnormalities | Microsoma, macroglossia, visceromegaly, embryonal tumors, omphalocele, hypoglycemia |

| Sporadic hemihypertrophy | Unknown | Enlargement of one side of the body or part of the body |

| Simpson-Golabi-Behmel syndrome | X-linked recessive | General overgrowth in height and weight with characteristic facial features |

Step 3: Operative Steps

Incision

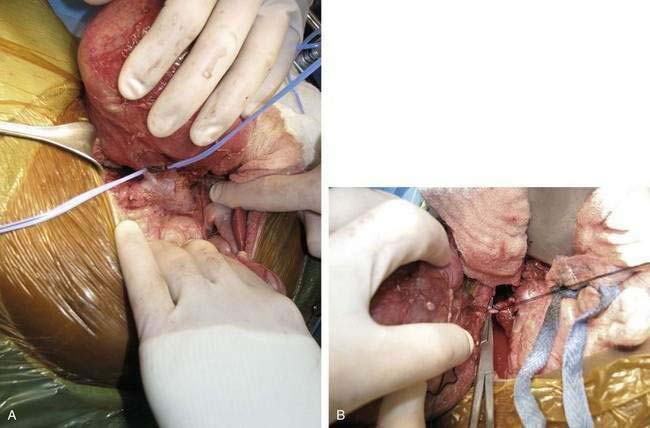

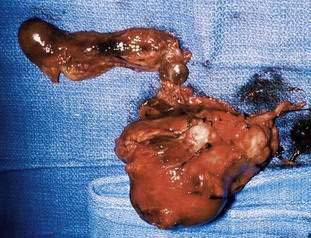

Tumor/Kidney Removal

Lymph Node Sampling

Central Venous Catheter Placement

Special Circumstances

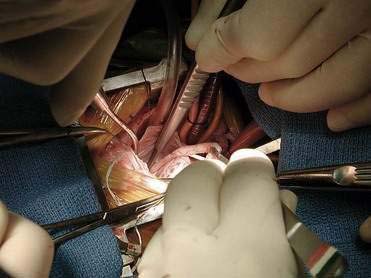

Tumor Thrombus

Bilateral Wilms Tumor/Solitary Kidney

Step 4: Postoperative Care

Fluid Management

Histology and Stage

| Stage I | Tumor limited to kidney, completely resected. The renal capsule is intact. The tumor was not ruptured or biopsied before removal. The vessels of the renal sinus are not involved. |

| Stage II |

The tumor is completely resected, and there is no evidence of tumor at or beyond the margins of resection, although the tumor extends beyond kidney, as evidenced by any one of the following criteria:

|

Step 5: Pearls and Pitfalls

Assessment of Resectability of the Primary Tumor

Tumor Biopsy

Tumor Rupture and Spill

Lymph Node Sampling

Mistaking Neuroblastoma for Wilms tumor

Postoperative Intussusception

Pulmonary Metastases

Breslow NE, Collins AJ, Ritchey ML, et al. End stage renal disease in patients with Wilms’ tumor: results from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Group and the United States Renal Data System. J Urol. 2005;174(5):1972-1975.

Davidoff AM, Giel DW, Jones DP, et al. The feasibility and outcome of nephron-sparing surgery for children with bilateral Wilms’ tumor: the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital experience: 1999-2006. Cancer. 2008;112:2060-2070.

Ehrlich PF. Wilms’ tumor: progress and considerations for the surgeon. Surg Oncol. 2007;16(3):157-171.

Ehrlich PF, Hamilton TE, Grundy P, et al. Wilms’ (National Wilms’ Tumor Study 5). The value of surgery in directing therapy for patients with Wilms’ tumor with pulmonary disease: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Group (National Wilms’ Tumor Study 5). J Pediatr Surg. 2006;41(1):162-167.

Ehrlich PF, Ritchey ML, Hamilton TE, et al. Quality assessment for Wilms’ tumor: a report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study-5. J Pediatr Surg. 2005;40(1):208-212.

Green DM. Controversies in the management of Wilms’ tumour—immediate nephrectomy or delayed nephrectomy? Eur J Cancer. 2007;43(17):2453-2456.

Kalapurakal JA, Dome JS, Perlman EJ, et al. Management of Wilms’ tumour: current practice and future goals. Lancet Oncol. 2004;5(1):37-46.

Paxton V, Dickson PV, Sims TL, et al. Avoiding misdiagnosing neuroblastoma as Wilms’ tumor. J Pediatr Surg. 2008;43(6):1159-1163.

Ritchey ML, Shamberger RC, Haase G, et al. Surgical complications after primary nephrectomy for Wilms’ tumor: report from the National Wilms’ Tumor Study Group. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192(1):63-68.

Shamberger RC, Guthrie KA, Ritchey ML, et al. Surgery-related factors and local recurrence of Wilms’ tumor in National Wilms’ Tumor Study 4. Ann Surg. 1999;229(2):292-297.

Shamberger RC, Ritchey ML, Haase GM, et al. Intravascular extension of Wilms’ tumor. Ann Surg. 2001;234(1):116-121.