Chapter 33 Wilderness Neurology

For online-only figures, please go to www.expertconsult.com ![]()

It is essential for practitioners in wilderness settings to have a working knowledge of neurology and to be able to diagnose and treat patients without recourse to specialist investigation, especially computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Circumstances will vary depending on terrain, weather, and the availability of emergency transport (Figure 33-1, online).

Preliminaries: History and Examination

Nervous system examination need not be lengthy or complex. A short neurologic examination (Box 33-1) takes less than 5 minutes. Much can be done without any special equipment; a tendon hammer can be improvised easily, and lack of an ophthalmoscope rarely makes a great difference to diagnosis and management.

BOX 33-1 Five-Part Short Neurologic Examination

Try to answer the following critical questions, using the story and examination findings:

Incidental Neurologic Conditions

Headache after Head Injury

The vast majority of headaches that occur after trauma—even those that last for several months—are not caused by serious intracranial pathology. However, subdural and extradural hematoma (see Chapter 21) must be considered in the aftermath of head injury. Both are rare in the absence of corroborating physical signs.

Wilderness Guidelines for the Diagnosis of Headache

Epilepsy

Emergency Management of Seizures

Status Epilepticus

Status epilepticus, which is also known as status (Box 33-2), involves the occurrence of continuous seizures (two or more) without fully recovering consciousness. More than 50% of cases of status occur without a previous history of epilepsy. Status is associated with a mortality rate of 10% to 15%.

BOX 33-2

Status Epilepticus

Doses from Clarke C, Howard R, Shorvon S, et al: Neurology: A Queen Square textbook, Oxford, UK, 2009, Wiley Blackwell Publishing, p. 235.IV, Intravenously.

One should have an established protocol. Box 33-2 describes such a protocol that has been adapted for wilderness use. For the emergency kit, one method is to carry injectable and rectal diazepam, injectable lorazepam, injectable phenytoin, and buccal midazolam with a bag-valve-mask device and several airways. One also needs to cope with the aftermath, so oral antiepileptic drugs (e.g., phenytoin, carbamazepine) should be available for continuing therapy.

Syncope and Related Phenomena

Other Causes of Sudden Attacks and “Funny Turns”

Paroxysmal Dyskinesias

Paroxysmal dyskinesias are exceptionally rare causes of sudden episodes of abnormal limb movement.

Sleep

Sleep Management

Meningitis and Encephalitis

Clues to Specific Varieties of Bacterial Meningitis

Possible infecting organisms are shown in Table 33-1. However, in wilderness practice, treatment for an unknown pyogenic organism will be required.

| Petechial rash | Meningococcal meningitis |

| Skull fracture | Pneumococcal infection |

| Ear disease | |

| Congenital central nervous system lesion | |

| Immunocompromised patient | Human-immunodeficiency-virus–related opportunistic infection |

| Pleuritic pain with or without rash | Enterovirus infection |

| International travel | Possible malaria or poliomyelitis |

| Environmental issues (e.g., polluted water, canals, sewage) | Leptospirosis |

Emergency Wilderness Management of Meningitis

Table 33-2 indicates a practical treatment approach, but it is important that up-to-date information about treatment protocols, potential allergies, and drug side effects is sought before embarking for a remote area.

TABLE 33-2 Antibiotics for the Treatment of Possible Acute Bacterial Meningitis

| Suspected Organism | Antibiotic | Alternative (e.g., in the case of allergy) |

|---|---|---|

| Unknown pyogenic | Cefotaxime (2 g IV every 4 hr) or ceftriaxone (2 g IV every 12 hr) for 7-14 days | Benzylpenicillin (penicillin G; 2.4 g given IV every 4 hr for 7-14 days) with chloramphenicol (50-100 mg/kg/day divided given every 6 hr to a maximum of 4 g/day) |

| Meningococcus | Benzylpenicillin* | Cefotaxime* or ceftriaxone* |

| Pneumococcus | Cefotaxime* or ceftriaxone* for 14 days | Benzylpenicillin* for 14 days |

| Haemophilus | Cefotaxime* or ceftriaxone* for 14 days | Chloramphenicol* for 14 days |

* Dosing information for these medications can be found in the text of this chapter.IV, Intravenously.

Doses from Clarke C, Howard R, Shorvon S, et al: Neurology: A Queen Square textbook, Oxford, UK, 2009, Wiley Blackwell Publishing, p. 292.

Transient Cerebral Ischemia and Stroke

Diagnosis of Transient Ischemic Attack

TIAs cause a sudden loss of function, usually within seconds and without a prelude. By definition, they last less than 24 hours, and they usually last only minutes or hours at most (Table 33-3).

| Anterior (Carotid) Circulation | Posterior (Vertebrobasilar) Circulation |

|---|---|

| Amaurosis fugax | Diplopia, vertigo, and vomiting |

| Aphasia | Choking and dysarthria |

| Hemiparesis | Ataxia |

| Hemisensory loss | Hemisensory loss |

| Hemianopic visual loss | Hemianopic or bilateral visual loss |

| Tetraparesis |

Transient Ischemic Attack and Stroke in Special Circumstances

Sudden neurologic events occur after underwater dives and at high altitude. Diving problems, decompression sickness, and the dangers of syncopal episodes after shallow dives are discussed in Chapter 77.

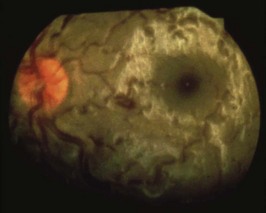

With HACE, a stroke-like event may be the first sign of brain edema, and it may occur out of the blue in well-acclimatized climbers at extreme altitudes (i.e., usually above 6500 m [21,325 feet]). This is in contrast with the typical cases of HACE that occur at around 5000 m (16,404 feet) with headaches and ataxia, when there is an apparent failure of acclimatization. Papilledema in a well-acclimatized man at 7600 m (24,934 feet) with sudden ataxia is illustrated in Figure 33-2.

Weak and Numb Hands, Foot Drop, Pressure Palsies, Back Pain, and Cervical Disc Disease

Lumbar Back Pain: Lateral and Central Disc Protrusion

Acute low back pain of disc or facet origin is common, and it is discussed in Chapter 21. One valuable emergency treatment is gentle spinal manipulation if pain and circumstances allow. My preferred method is to lay the patient supine on a firm, flat surface. Examine the patient neurologically, and check hip, knee, and ankle joint movements. Sitting astride the supine patient, grasp one knee and thigh in a firm but gentle elbow lock. Firmly flex and rotate the hip so that the patient’s flexed knee, which is held in your elbow, points toward the opposite hip of the patient. Although this is primarily a treatment for facet joint problems, it is generally worth trying. Keep all patients with back pain active if at all possible.

Cervical Disc Lesions

Acute neck pain is covered in Chapter 21. The potential neurologic sequelae of degenerative cervical disc disease are lateral disc protrusion that causes a cervical root lesion and central disc protrusion that causes spinal cord compression and paraparesis. Lateral cervical disc protrusion can be intensely painful, but it is usually self-limited. Central cervical disc protrusions are frequently painless, may cause no neck symptoms, and are usually progressive; they require urgent specialist treatment.

Acute Vertigo

Preexisting Neurologic Conditions

Epilepsy

Cerebrovascular Disease

Practical Guidelines:

Clarke C, Howard R, Shorvon S, et al. Neurology: A Queen Square textbook. Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell Publishing; 2009.

Clarke. Neurological disease. In Clark ML, Kumar PJ, editors: Clinical medicine, ed 7, St Louis: Saunders, 2009.

Johnson C, Anderson RS, Dallimore J, et al. Oxford handbook of wilderness & expedition medicine. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press; 2008.