Chapter 105 Wilderness Medicine Education

For online-only figures, please go to www.expertconsult.com ![]()

The features of wilderness medicine that make it so attractive to an ever-increasing number of health care professionals also present challenges to its educational programs. The need for special attention to the learning process in the discipline has been called for in the peer-reviewed literature since the early 1990s.3,4,18,52 Some work has been done at the individual program level to incorporate evidence supporting modern concepts of adult education in health care. However, there are no universally accepted standards for the delivery of education or assessment of outcomes unique to this diverse discipline.

The spectrum of learners in wilderness medicine closely mirrors the types of experiences to which the discipline applies.76 On one end of the spectrum are laypeople who seek to acquire knowledge on basic first aid or exotic travel for reasons of safety or security. Next are those seeking formal search and rescue medical training, including conventional emergency medical technician (EMT) and paramedic training tailored to the wilderness setting. The next level is represented by expeditionary advisory and emergency care provided in isolated circumstances by multiple types of providers, including EMTs, nurses, and physicians. Finally, there is the group of technically oriented researchers and other professionals who seek topic- or environment-specific experience and fellowship with others that share their level of interest (Figure 105-1, online).

FIGURE 105-1 Wilderness medicine learners are a diverse group with varied backgrounds, skills, and motivations for learning.

(Courtesy Fred Baty.)

In 1991 the Wilderness Medical Society (WMS) proposed a model for developing curricula to teach wilderness prehospital emergency care (WPHEC).76 It was hoped that this would stimulate movement toward a disciplinary standard that would elevate the quality of this type of training throughout the United States and abroad. In this work the WMS noted the differences between wilderness and urban prehospital emergency care. These lie at the heart of what makes wilderness medicine education unique. They are summarized as follows:

FIGURE 105-2 Wilderness medicine is a discipline practiced and learned in and around the extremes of environment.

(Courtesy Fred Baty.)

A unique aspect of wilderness medicine is the close relationship of the often-harsh environment to maintenance of the knowledge base. Wilderness medicine practitioners are typically action-oriented professionals who prefer to learn and practice their craft in the outdoors. This speaks to the very nature of wilderness medicine. However, despite this link, there is a need to separate preparation and conditioning for the environment from education in order to facilitate the learning process.3 Logistics and varying skill levels of learners make it unreasonable to carry out full practical exercises for every wilderness medicine topic in every venue at which they are taught.

Principles of Adult Learning

Basic Principles

Learners generally prefer educational approaches that focus on concepts and principles instead of fact-based information.75 A concept derived from the teachings of Sir William Osler and known by nearly every classically trained physician holds that one should never spend time memorizing facts from a book at the expense of hands-on patient contact. This is why problem- and scenario-based learning has been incorporated into most modern health care education programs. The nuances of problem solving cannot easily be garnered from a book. Osler might say that precious time is best spent at the bedside rather than on what the student can be expected to read alone.

Learners respond favorably when they are able to participate in developing their own learning objectives.75 This is a pronounced difference between adult and child educational processes that should be properly accounted for and leveraged. The negotiation process between student and teacher that leads to properly established objectives builds relationships and trust that are at the foundation of the adult learning process. Allowing this to occur may seem counterintuitive, especially to educators who adopt a more directive style of teaching. However, participation by learners in goal setting facilitates ownership of the process and leads to higher levels of performance.

Feedback to students may be the most important ingredient to solidify learning and complete the education cycle.75 To be effective, this should be direct, specific, and individualized to each learner. There are many reasons why this may not occur in health care education. They range from the simple logistics of managing large classes to litigation and are often cited for failing to use this powerful educational tool.

Concepts, Theories, and Models

The Education Cycle

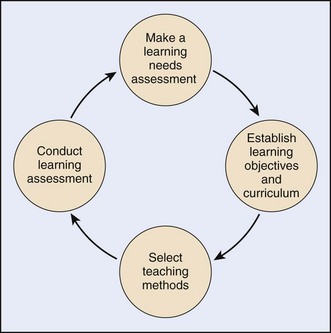

The notion that broad concepts of the process of learning can be described as a cycle is not new. Pattinson and Matthews58 recently applied it to wilderness medicine while planning a mountain medicine curriculum. As depicted in Figure 105-3, the program director first makes an assessment of the needs of the learners; he or she gets to know the audience. Next is the often-underestimated task of establishing tailored and focused learning objectives. The educator then selects teaching methods and settings that best accomplish the objectives while meeting the needs and expectations of the learners. Finally, after the experience, the educator makes an assessment to ascertain whether learning has occurred. This final step may be the most difficult and least attended of all. These elements will be addressed later.

Experience-Based Learning

Kolb’s model41 of learning is based on how individuals internalize and process learning experiences. Learners perform an action, referred to as a “concrete experience.” They then process the new information by “reflective observation.” Next they consider how the new information can be applied to their unique circumstances by “abstract conceptualization.” Having internalized the experience, they try it by “actively experimenting” with what they have learned to apply it in new and unique ways. This model is reflected in several of the teaching and assessment techniques discussed later, especially those that address concrete skills.

Education and the Human Organism

Setting the conditions for learning can be conceptualized by using Maslow’s famous explanation48 of how humans address fundamental needs. Vella’s work71,73 in popular education extends these ideas to the realm of education in the social context but still deals with the rudiments of human nature.

Unmet physiologic needs, such as warmth and hunger, tend to impair learning as the human organism prioritizes toward survival. Unfulfilled security needs, which Vella71 refers to as safety, distract from any process that does not pose an immediate threat. In adult education, safety issues may be subtle. Students who do not feel free to voice opinions or reveal a deficiency may be said to lack a safe learning environment. Identification with a group of learners addresses the need for belonging that is used by organized team sports and the military. The need for self-esteem may be met by recognition for academic achievement in front of one’s peers. Finally, the highest level of Maslow’s concept, self-actualization, is represented by satisfied expectations on the part of the learner. By expanding these concepts and directly addressing each in the classical hierarchical fashion, a program director can remove many obstacles to learning during the planning phase of the educational experience. A learning event that accounts for them will have a high likelihood of success and impact the student’s life well beyond the experience.

Learner Sophistication

Another powerful tool available to teachers is the identification of the level of understanding, or “sophistication,” of the learner. Neal Whitman proposed four levels that learners traverse as they acquire new knowledge and skills. Correctly matching teaching methods to these will improve the overall experience by saving time and increase the likelihood of fully meeting expectations.75

Principles of Androgogy

There have been numerous efforts to roll learning theories together into a concise package of tools for health care education. To this end, the work of Malcolm Knowles is widely read and often cited by education academics. He put structure to the concept of helping adults learn and called it “androgogy.” He suggested that through the principles of androgogy, adult learners are most successful when they are assisted in the process rather than directed through it.39 Knowles made five basic assumptions about adult learners from which he derived his principles. They can be summarized as follows: (1) Adults tend to have internally and not externally focused motivations for learning; (2) The learning process should be related to solving real-life problems; (3) Existing knowledge and experience greatly influence learning; (4) Self-direction improves the learning experience; and (5) Adults learn best with problem-based rather than subject-based methods. Knowles’ seven principles of androgogy are summarized in Box 105-1.

Learner-Centered Education

Jane Vella has applied learning theory in unique ways to the social context across different cultures. She recognized that education lay at the heart of many social issues. The teacher’s message is often lost in the delivery because of avoidable cross-cultural and interpersonal obstacles. She maintains that the key to adult learning is clear dialogue between the teacher and learner.71–72 Educators too often fail to establish productive dialogue and hence select ineffective teaching approaches. Vella suggested that traditional hierarchical teacher-student roles be discouraged. Teachers become facilitators. Barriers to dialogue are “addressed and eradicated.” She offered to popular education a paradigm that places the learner at the center of the educational universe. Her principles link theory to practical use in a way that enables learning in challenging circumstances. Vella’s principles are summarized in Box 105-2.

Learning-Oriented Teaching Model

Cate and associates9 recently published their notion of a model of teaching based on concepts from educational psychology. Their proposals are meant to influence all aspects of adult education, especially those of curriculum design, teaching techniques, and teacher assessment. An attractive feature is a method to “inventory” and match teaching and learning styles to improve outcomes. The authors build a model around what they identify as the “components of learning” and the “amount of guidance” that learners require to navigate the experience. Their premise is that, because education seeks to enable people to “function independently,” the process should foster self-regulation of learning. In the model, learners mature from “externally guided” learning through “shared guidance” to self-guided or “internally guided” learning. This applies to both cognitive (what to learn) and affective (why to learn) components of learning.

Putting It All Together

Theories and models are meaningless without practical application. Directly applying ideas from theorists with diverse backgrounds and agendas into the realm of wilderness medicine education is difficult. Kaufman38 recently reviewed several adult education theories in the context of health care education. He examined them for key areas of commonality and offered simple principles to “guide” medical educators as they think about and plan educational experiences (Box 105-3). Wilderness medicine educators can easily adopt these.

Educational Techniques

There are a myriad of delivery techniques available to the modern medical educator. Despite being extensively studied across many disciplines, identifying a method of educating the medical learner in a way that results in consistently improved performance and outcomes exceeding other methods remains elusive.62 To be sure, there is no single method that is effective for all types of learners in all settings. In wilderness medicine this is compounded by the degree to which hands-on skills depend upon a solid grasp of basic science and the flexible application of clinical medicine.

Selection of the most effective methods depends largely on the setting as well as the expectations and needs of learners. The prudent curriculum designer will avoid incorporating attractive methods of presentation designed to capture attention without substantively improving the educational quality. Schweinfurth characterized the problem of finding the right mix of techniques when he described his use of interactive training among otolaryngology residents. He referenced comments from a focus group of trainees, discussing what he called “innovative learning strategies.” He found that learners were hesitant to endorse innovative strategies in order to avoid complex exercises that may compromise limited time available to conduct didactic sessions. His learners found some attempts at innovation as ‘too experimental’ or a ‘waste of time.’63 The lesson should be that innovation, as an end in and of itself, may not serve the learner. Innovation that causes the learner to walk away with a sense of improvement can be considered successful.

Lecture

Lecture is the most often used educational technique. It offers several important advantages. Large amounts of information can be delivered in relatively short periods of time. Planning is generally easier for the lecture format. It requires little logistic support and only one teacher. It works well for highly technical information that the learner will most likely have to study again in order to internalize. Lectures can be easily enhanced with audiovisual aids. All of this adds up to a degree of efficiency that is highly attractive to the resource-limited educator. In one small but interesting study, Reed62 illustrated that, despite the availability of highly technical and resource-intensive teaching methods, a simple “low-cost, low-tech” lecture approach can offer rewards in terms of improved skill performance (Figure 105-4, online).

The lecture technique has several equally important disadvantages. Learning is highly dependent on the delivery skill of the teacher. Because it is passive, many adult learners do not respond as well to this approach. It is generally accepted that levels of retention of material presented by pure lecture are lower than more active teaching techniques.67 There is generally limited opportunity for hands-on applications and practice. Thus the usefulness is limited in some areas of wilderness medicine that are largely skills oriented. The more restricted the opportunity for student questioning and dialogue, the less effective this technique becomes. Students can often more effectively learn by themselves information to be presented by lecture. Brookfield8 discussed methods to enhance the lecture as a means to communicate information (Box 105-4).

BOX 105-4 Methods to Enhance the Lecture

Problem-Based Learning

A highly effective trend in health care education is the use of problem-based learning (PBL). PBL can take various forms, but generally learners are presented with a problem and are guided through a structured discussion that leads to a preestablished solution. This learner-centered approach has proven popular among students and demonstrates comparable outcomes when compared with other, more traditional formats. An interesting aspect to PBL is that student-led experiences tend to be more highly favored among participants than those facilitated by faculty, yet the outcomes remain at least comparable in terms of satisfaction and examination scores.29,66

PBL offers great versatility to the curriculum planner. It can be used whether the focus is on acquiring pure fact-based knowledge or practical skills. It is most often applied in the small-group setting and therefore may pose logistic challenges in some space and resource-limited settings. It complements the strengths of small-group learning in that it reinforces communication and problem-solving skills, teamwork, individual responsibility for learning, and the need to share knowledge.77 It tends to give the best results when it is structured and forces learners to use critical thinking skills. It fosters the process of analysis, organized problem solving, and decision making using group discussion to direct and reinforce learning. The general format for PBL is presented in Box 105-5.5

Scenarios and Role-Play

Scenario-based and role-play training is familiar to prehospital emergency care educators but less widely used in traditional medical education. It maximizes many of the strengths of newer approaches to adult education because it guides self-motivated students through a process of “discovery” of the information.45 The main role for teachers in this format is to facilitate, not direct, the learning process.30 Being an expert in the clinical details of each case is less important than understanding how to apply problem-based learning. This method is often scripted and makes use of actors, props, and moulage to simulate real-life situations. The logistics of carrying out this aggressive training technique may be prohibitive to some programs, but the investment is worth the effort in terms of improved outcomes and retention of knowledge by learners. Nearly all organizations that train prehospital wilderness medicine practitioners use some form of complex case- or scenario-based learning program. The use of role-play has benefits beyond the teaching and development of technical skills. One recent randomized controlled trial confirmed the utility of using role-play when teaching technical skills in the area of communication. The authors of this small study of 36 medical students randomized to learn a skill with and without role-playing concluded that, although there were no differences in technical performance between groups, the introduction of role-play as a training method enhanced the realism of technical skills training and led to better patient-physician communication53 (Figure 105-5).

Discussion

There are two basic modes of discussion-based learning.43 The Socratic questioning method challenges students to identify the most important features of a specific problem and then reconstruct it using general principles that are the true focus of the discussion. Developmental discussion approaches the problem in parts. It keeps all students focused on one part at a time and takes advantage of the group setting to ensure that teaching points are addressed.

Teacher-facilitators may highlight the discussion with the powerful tools of analogy, discovery, and induction to stimulate learning and ensure retention.16 Analogy illustrates concepts by asking students to visualize using examples with which they are already familiar. The process of discovery leads students through a sequence of steps from the most basic to the more complex to guide them to the final goal of deeper understanding of the principal learning objective. Induction asks students to take general lessons from specific examples or experiences, make comparisons, and draw new conclusions relevant to the learning objective. These three techniques can be applied in any setting that involves learner interaction with the teacher.

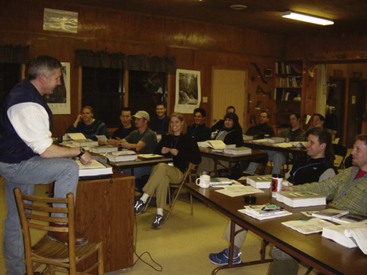

Small-Group Learning

The selection of a teaching method is highly influenced by class size and quantity of information that must be learned. Large classes that must digest substantial amounts of information tend to push faculty into selecting passive modes of teaching. The traditional CME conference at which hundreds of attendees review highly technical material is an example of this. However, passive, lecture-based methods are not the most effective and often not the most efficient for all types of learning, especially in wilderness medicine. It is now widely accepted that skills-based learning presented in a small-group setting is a better way to teach practical skills44 (Figure 105-6, online).

To understand group learning is to understand how the individuals within the group interact.

Bruce Tuckman’s original concept of the developmental sequence of small groups should greatly influence how teachers plan and conduct these activities.26,36,69,70 The general strategy for teachers is to become familiar with the stages, recognize their manifestations, and use a planned approach that gradually releases control of the teaching process to the group as members become more able to direct their own learning.

The role of the teacher in a small-group setting should be oriented toward facilitation of learning rather than direct delivery of material. However, the teacher remains accountable and cannot take a completely hands-off approach and expect that objectives will be met. By attending to the details of process, the teacher ensures that the learners do not have to perform this task. The teacher creates the proper learning environment and keeps the process on track. Some common mistakes made by small-group “facilitators” include the following: the teacher presents a lecture; the teacher talks too much; students do not participate unless prompted or directly questioned; the students lack preparation for the session (e.g., prereading); there are overbearing, domineering students; and participants want to be provided a quick and simple solution to the problem rather than engage in the process of group discovery.35

Despite not being part of the learner group, the teacher has great influence over the process and the outcomes. A poorly prepared teacher ignores the internal dynamics of the group and sets up the experience for failure. Some techniques available to avoid these problems include: agreed-upon rules for the conduct of sessions; clearly stated tasks and objectives; use of the rhetorical method of questioning to stimulate thinking; taking a lengthy pause after posing a question, allowing students to answer; not offering immediate solutions or guidance unless participants appear to be taking the wrong path; attending to body language and mannerisms of all participants, both when they are speaking and when they are listening; addressing the entire group, rather than a single student, with mannerisms and eye contact.35

The general steps in preparing for and conducting small-group teaching are summarized as follows:

Distance Learning

The advantages that the Internet offers to medical educators are many. Even courses that are not offered as complete web-based packages can be supported by limited Internet applications such as e-mail, distribution of materials, enrollment, needs assessments, and testing. To this can be added videoconferencing, discussion boards, live topic-specific chat rooms, and presentation of live events via video streaming. Nearly any software application that can be used on a home computer can be offered in some fashion over the Internet. With the advent of high-speed connectivity and constantly changing security programs, obstacles to efficiency and learner security have been minimized. Virtual learning environment software enables all of these applications to be managed efficiently while keeping the focus on the learner and not the technology.32

Field Experiences

Medical schools and residencies are following the lead of commercial WPHEC programs and moving learners out of the classroom and into the field.45 Rotations and electives that include field-training experiences of various lengths are now highly sought after. These have the effect of maintaining high levels of student interest and satisfaction. They offer direct relevance and immediate application of newly learned skills. When coupled with effective group process and feedback, the benefits of field training make this a powerful venue for skills-oriented education. These experiences are most often part of an overall curriculum that incorporates other techniques, such as lecture and problem-based learning, in a didactic setting (Figure 105-7).

Concerns include safety and security of participants as well as liability issues for the sponsoring organization. The logistic support package can be expensive and complex. The quality of the experience is greatly influenced by uncontrollable factors such as weather and climate. Proper screening and selection of participants are critical to success, especially in programs that are conducted in remote locations or in physically demanding environments. Multiple techniques, such as scenarios and hands-on practical exercise, can be applied simultaneously to maximize the learning experience. Field training affords an opportunity to introduce nonmedical skills such as leadership, wilderness survival, and land navigation.45 This not only generates interest but also creates well-prepared learners and an overall lower level of risk.

Competency-Based Medical Education

Description

Since 1981 the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) has served as the principal accrediting organization for physician residency training programs in the United States. As such, the ACGME drives improvement in the overall quality of health care in the United States through development of policies governing how physicians are trained and by accrediting training programs based on those policies.2,47

GME programs now must teach and evaluate residents using techniques and tools based on six core competencies. Moreover, it is a requirement that accredited GME programs incorporate these competencies into curriculum design, development of training objectives, and building of 360-degree assessment systems for both faculty and learners. Programs must also validate the data and methods they use to train and assess performance using external measures2,37 (Box 105-6).

Applicability to Wilderness Medicine Education

As with most GME programs that have been able to grow and adapt existing methods to align with the ACGME competency-based requirement, wilderness medicine programs must adapt. For example, programs that offer medical school or residency elective experiences will have to demonstrate curricula based on well-built, measurable objectives that are based on the ACGME core competencies. Instruments, such as summative assessments of learners seeking credit from parent academic institutions, will require competency-based formatting. Fortunately, most wilderness medicine educational programs incorporate fundamental concepts of adult education discussed earlier and likely require only modest changes to existing curricula, training methods, and assessment tools. Not all wilderness medicine programs will require full or strict compliance with ACGME guidelines with respect to outcomes-based education. Those that wish to be fully ACGME compliant should follow the general guidelines offered by the ACGME. Programs are expected to provide learning opportunities in each general competency domain. They will use multiple and overlapping methods to assess learners and outcomes data to enable them to demonstrate continuous improvement in the educational program. Competency-based assessment tools are widely available on the Internet and can be modified for almost any wilderness medicine educational setting. When evaluating processes for ACGME alignment, programs should consider three areas. Do the learners achieve the established learning objectives? Can the program demonstrate this with evidence? How does the program demonstrate continuous improvement in its educational process?47

A number of assessment tools that have been developed to enable generation and tracking of outcome metrics are available through the ACGME Outcome Project Toolbox.2 Each of the tools has been made available for use by residency programs and may be adapted to nearly any medical education situation. Not all tools are suitable to assess all six competencies. Therefore, ACGME advocates using several tools when assessing learners in any given setting. This strategy results in a more valid overall competency-based assessment of each learner.

Assessing Learners’ Needs

Performing a proper assessment of the needs of students before designing a curriculum leads to a fulfilling experience for all. Jane Vella claims that this critical step is necessary to “truly honor the time investment of the learner and create the conditions for meaningful dialogue between learner and teacher.”71 People whose motivations for learning are ignored “quickly become bored and indifferent.” They often walk away from the experience dissatisfied or without completing the program. Some examples of information the wilderness medicine course planner would want to know are:

Learning Objectives

A learning objective is a collection of words, pictures, or diagrams that tells others what the educator intends for learners to achieve.46 When properly written, objectives establish outcomes rather than describe process. The basic purpose of teaching is to facilitate learning resulting in measurable outcomes. A learning activity is a process designed to achieve a result. What students actually learn is the result and should be described in advance by objectives.25 The basic functions of learning objectives are to:

An objective is constructed by describing an activity that elaborates specific knowledge or skills that a learner will be able to demonstrate following a successful learning activity. Well-written learning objectives are measurable by written testing, observation, hands-on problem solving, or other methods of assessment. Words or phrases such as know, think, appreciate, learn, comprehend, remember, perceive, understand, be aware of, be familiar with, have knowledge of, and grasp the significance are difficult to measure and are of little use when writing learning objectives in wilderness medicine.10 Examples of learning objectives that illustrate the concepts of being specific and measurable are as follows: The student will be able to …

Strong objectives, in addition to being performance based, specific, and measurable, are preceded by a condition statement to set the stage and aid with measurement specificity.46 In writing objectives, answer the following questions: “What should the participants be able to do, and how well must they do it?” Objectives must be clear and attainable. They are often constructed in an “if … then” sequence to facilitate clarity. Focus on acquisition or reinforcement of a specific element of knowledge or skill.25 Recommended styles for constructing objectives include the following:

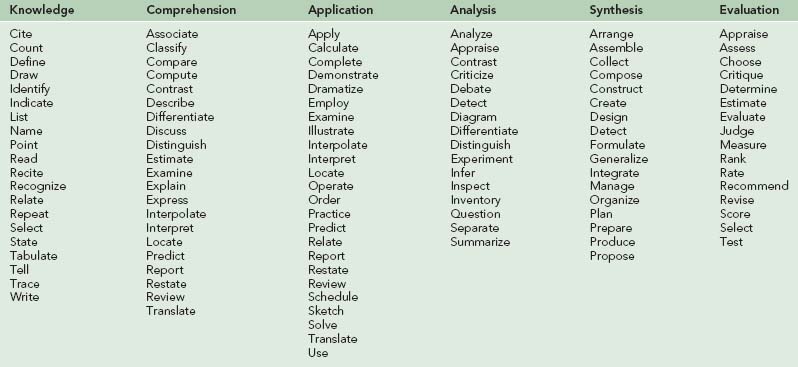

This last phrase is followed by a specific performance verb and the desired learning outcome. Examples of performance verbs are found in Table 105-1. The following is an example of a properly prepared set of objectives:10

Assessing Learning

The last step in the education cycle (see Figure 105-3) is making a formal assessment of whether or not learning has occurred.58 There are several reasons for testing in wilderness medicine education beyond the obvious need to validate and certify students. Learning assessment can be a valuable extension of the learning process. Kromann recently reported that “testing as a final activity in an in-hospital resuscitation skills course for medical students increased learning outcomes compared with spending an equal amount of time in practice.”42 Students seldom come away from a properly conducted and reviewed examination without having learned something. It can be said that this type of learning by assessment is the capstone of knowledge synthesis. Each examination completes the education cycle at a particular level and allows progression to the next with a higher degree of competence.

Timing of Evaluation

The learner uses feedback and information gained from formative evaluations to improve performance during the learning event or course. To be effective, formative evaluations must be provided to learners before the end of the training period. Although assessments rendered early in the training period allow more time for modifying performance, there may have been insufficient time for adequate and comprehensive assessment. Likewise, evaluation made later in the training period allows for more accurate and comprehensive assessment, but there may remain insufficient time for satisfactory remediation. Unless there are compelling reasons to render evaluations early (e.g., when questions of safety or impropriety arise), those provided to learners at the approximate midpoint of the training cycle tend to work the best. These should be scheduled, anticipated by learners, and well prepared and presented by faculty. Programs that use anonymous evaluation tools (e.g., at the end of a course) must collect and collate results from learners and faculty and analyze the results. This may decrease the usefulness of the instrument by causing a separation of results from the actual training event.13

Feedback

Regardless of which tools a program incorporates into the overall assessment system, dedicated opportunities for immediate feedback on performance must be used to ensure maximal learning. Although formative and summative evaluations capture performance over a given period of time that may contain numerous individual events, immediate feedback is designed to give learners the opportunity to make adjustments based on their performance during specific events or very brief and focused training periods. Learners that are not provided this type of feedback will be left to rely on happenstance to succeed at course objectives (Figure 105-8).

Feedback is especially important in the types of hands-on, scenario-based clinical training frequently conducted during wilderness medicine courses. Hands-on skill training requires concrete demonstration of proficiency and does not rely on an evaluator making presumptions of a learner’s thought processes to make an assessment. Properly conducted feedback makes an immediate connection between outcomes of learner actions and expectations as established by goals and objectives. This solidifies learning in ways that are impossible with other evaluation tools. However, the benefit decreases rapidly as time from the event to delivery of feedback increases. Effective feedback is given by the person who observes the event and is done so immediately after completion.13

The 360-Degree Evaluation

As part of the ACGME focus on outcomes-based education, accredited residency training programs in the United States provide objectives-based assessments of learner performance in six core competencies (described earlier). In addition, programs now incorporate an assessment system that receives input from multiple evaluators. This is also called a 360-degree evaluation system. The ACGME lists this type of evaluation method as a “highly recommended” tool.2

The 360-degree evaluation accepts contributions to the development of learners by all types of people in the general sphere of his or her influence. It offers training programs a process by which numerous and varied perspectives may be used to more accurately assess all aspects of performance. It is presumed that observations of learners made from different perspectives are more valid than are traditional, more narrowly focused assessments. Assessment tools that allow for efficient organization of 360-degree evaluations are available in the ACGME Toolbox and are generally regarded as valid when used in correct circumstances.2,13,28

The usefulness of 360-degree evaluations in specific wilderness medicine training programs has not been evaluated, and instruments relevant to these settings have not been proposed. However, those widely available and validated within graduate medical education can easily be modified and incorporated. The usefulness of this method of learner evaluation will depend on factors such as length of the course, contact with noncourse participants (e.g., role-players and patients), and types of events used as training tools (e.g., small-group field-training events); 360-degree evaluations may be found to be more relevant to courses that are longer, with more varied types of learner interactions over time (Box 105-7).

Reliability and Validity

Two key concepts to understand when designing learning assessment tools for wilderness medicine courses are reliability and validity. These are applied separately when discussing written and skills-oriented testing.35,65 They are particularly relevant to WPHEC courses such as WFR or wilderness emergency medical technician (WEMT), which rely heavily on skills-based testing.

Schuwirth and van der Vleuten proposed a list of criteria to compare the advantages and disadvantages of various types of written test formats and questions35: reliability and validity (as discussed earlier), educational impact (how students prepare for examinations, hence learn the material), cost-effectiveness (expense in terms of money and time), and acceptability (how both students and teachers view the examination’s effectiveness and relevance). To account for these factors, the most preferred method of developing written examinations is to use several types of test questions in each instrument. The types of examination questions that may be considered include true-false, single best answer multiple choice, multiple true or false, short answer “fill in the blank,” essay, case-based key feature, and extended matching. A thorough treatment of each can be found throughout the literature.

Evaluating the Assessment Tool

The process of test item analysis correlates the number of examinees that missed a given question with overall test scores.15 This can be done on two levels. The first is within the group that was being tested at a given course. The second is over a period of time among several groups that took the same examination. As with any internal assessment tool, the latter style leads to stronger conclusions but takes longer to complete. Internal pattern analysis of test scores can reveal that either the instruction was bad or the test question was not well written. The basic principle is that if a large percentage of students received a high score on an examination but a similarly large percentage missed a particular test item, then either construction of the item or the teaching method is likely at fault. This technique loses power and specificity at lower overall examination scores among those that missed the item(s) in question.

Skills-based learning assessments can be evaluated for quality using similarly simple analytical tools.15 The attendance comparison mentioned above is an obvious starting point when reviewing individual performance.

Teaching in Wilderness Medicine

Good Teachers

What of the act of teaching in wilderness medicine? What is unique about the discipline in comparison with other areas of health care education that calls for special attention to the delivery? As mentioned before, wilderness medicine instruction is often and understandably disconnected from the environment about which it informs. Teaching the fundamentals of altitude, depth, cold, or heat and their impact on the human condition requires that the initial knowledge base be largely acquired in a “safe” environment. The experiential phase that we presume solidifies learning for wilderness medicine practitioners often occurs in another setting at a different time, if it occurs at all. Therefore, to be effective, the material must be presented by faculty that possess the ability to captivate and motivate learners. Paul Auerbach proclaimed, “The enthusiasm of the instructor is plainly apparent and can carry or lose the day. Regardless of the educational technique chosen, one must be ‘into it’ or the students will be soon flocking out of it.”3

Just as wilderness medicine practitioners must draw from a solid base of knowledge to be creative when providing care in austere surroundings, wilderness medicine faculty must be familiar with and use all of the theory-based tools available to them to be successful, even in less-than-optimal teaching settings. Steve Donelan highlighted the issue by noting, “Instructors tend to assume that if students stay awake and interested, pass the tests, and write nice comments on the evaluation forms, then the course is successful.”14 Good teaching does not just happen. Highly effective wilderness medicine teachers are as proficient with the teaching skill set as they are with the clinical “tools of the trade” in their unique area of expertise.

As in highly technical health care fields, the credibility of wilderness medicine faculty is paramount. Beyond the obvious reasons for needing credibility as a teacher, most wilderness medicine learners are already well placed in their respective fields with years of educational experience behind them. Moreover, it is not uncommon for wilderness medicine faculty to be addressing participants that are not only proficient at the topic in question but may be leading experts or researchers in that area. According to Auerbach, “If a teacher wishes to do more than read from a script, he or she must have some first-hand experience in the environment. Students are better than we imagine at rating our technical skills.”3

For years medical educators have studied the notion that the best clinical teachers all display a common set of characteristics. Numerous authors list qualities of good teachers based on learner surveys and outcomes assessments.33,34,75 Some of these have special applicability to wilderness medicine education:

The Educational Environment

Hutchinson recently pointed out that “in adult learning theories, teaching is as much about setting the context and climate for learning as it is about imparting knowledge or sharing expertise.”32 Nearly everything that the teacher does influences either the students’ ability or willingness to learn. Wilderness medicine course planners that account for these factors will enjoy a much higher likelihood of success than those that simply present material with little accounting for process and environment. Two factors that can be influenced by providing the right environment are the motivation of learners and their perception of how relevant the material is to their lives. Adult learners are quick to identify a poorly prepared program. They derive their energy directly from the faculty and will respond in kind to the amount of effort that has gone into providing for the proper learning environment.

Although it is impossible to solve every problem in any setting that is remote or exciting enough to host a wilderness medicine educational experience, problems should be addressed to the extent possible. Decisions should be made early about the adequacy of the setting balanced against the need to conduct realistic training in or near the wilderness environment. Compromises may be made that trade some degree of realism for comfort and vice-versa. Potential problem areas should be made known to participants well in advance so that they may make choices about the importance of these factors and balance them against their own desire to receive the training (Figure 105-9).

Training Aids

Audiovisual

The basic roles of visual aids are to illustrate the organization of a topic as it develops, to reinforce or highlight key material, and to provide an organizational “anchor” for the group that allows members to take notes, think, pose questions, and keep pace with the session.17

Syllabus Material and Handouts

Handouts that are meant for preclass preparation should be provided before the session. Those meant to recap or summarize may be best provided after the session to avoid distraction.17 Some syllabus materials are meant to save students’ time in note taking by providing key points with spaces provided to fill in additional information. This serves the dual purpose of keeping students engaged and making them think about the information before summarizing it in their own words. This technique carries a risk that important information may be misquoted or missed entirely.

Simulations

Among the most thorough treatments of the history and perspectives of the use of simulation in medical education is offered by Gardner and Raemer, who describe the use of this educational tool in obstetrics and gynecology training. They point out that among all the techniques available for the transfer of medical skills and knowledge, “simulation is a practical and safe approach to the acquisition and maintenance of task-oriented and behavioral skills across the spectrum of medical specialties. It is a means to augment didactic instruction, providing an out-of-the-chair and hands-on experience in a safe environment without harming real patients.” The notion that nonhuman objects could be used to train medical practitioners is not new and is being used across many disciplines.6,56,68,74 As a model of complex skill training using a simulation-based mastery learning program to increase learner skills, Barsuk7 recently used simulated central venous catheter insertion to demonstrate improved performance that decreased complications related to central venous catheter insertions in actual patient care.

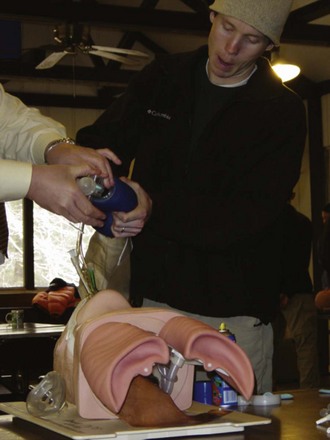

The incorporation of modern, computer-based technology across the spectrum of industries did not escape health care. Most medical schools and graduate medical education programs incorporate some form of simulation in their curricula.7,27 Computer-based simulation technology has evolved to the point of offering virtual world individual and team-based scenarios using preprogrammed patients to expand the breadth and depth of options available for medical education.57,64 Expectations for increased quality of medical training and the improved outcomes that result seem to contradict the decreased time allotted and increased resources required to conduct this training, as well as the associated expense. Training on virtual patients using interactive, computer-based clinical scenarios offers a potential solution11 (Figure 105-10).

FIGURE 105-10 The use of simulation technology in wilderness medicine education often involves simple, low-tech models to enhance learning.

(Courtesy Fred Baty.)

Simulation technology is being used increasingly in medical training settings to enhance team training. As with any team-based vocation, medical teams that frequently practice their interactions are more effective and efficient. Teams that use simulation tools along with scenario-based role-play will benefit greatly. This is particularly useful in first responder and many types of hands-on wilderness medicine training courses. The learning and reinforcing of basic teamwork principles are greatly facilitated by using scenario- and simulation-based training. These include leadership, followership, situational awareness, closed loop communication, critical language, standardized responses, assertive communication, adaptive behaviors, workload management, and debriefing31,54 (Figure 105-11).

Important factors to consider when planning training using patient simulation are the setting, the scene, acting, evaluation, and makeup (moulage).47 The setting can be either indoors or outdoors as long as the proper clues are available to the learners. Highly realistic indoor settings call for elaborate surroundings and are often unnecessary. The basic function is to allow learners to familiarize quickly with the details of the scenario and make treatment and resource allocation decisions based on that information. Outdoor settings add more realism and use fewer resources but are subject to limitations imposed by weather and terrain. Even though prehospital courses in wilderness medicine orient their curricula toward anticipating, recognizing, and managing clinical syndromes using limited, often improvised equipment, the use of prefabricated and prepositioned props may make the training more efficient and the assessments more reliable.

The ability of learners to mentally immerse themselves in experiences using simulations seems to be directly related to the quality of the learning experience.27 No matter the quality and high degree of fidelity of the simulation device used, the willingness of participants to “act the part” as though the situation were real for the duration of the training event facilitates the quality of their learning (Figure 105-12).

When available, makeup devices enhance learning by adding a high degree of realism. Makeup may consist of inexpensive improvised items or costly, anatomically correct moulage kits designed specifically for this purpose. The overriding concern when improvising or selecting moulage is whether it enhances or detracts from achieving the learning objectives of the scenario. If it directly supports the clinical syndrome being portrayed, then it is a good choice. If it does not, then it may confuse learners by causing them to make faulty assumptions. This has the overall effect of incorrectly learning material and leads to unreliable and invalid assessments (Figure 105-13).

The notion of computer-simulated training dates back to the 1960s. Modern applications are taking the concept to a new level in the field of health care education. Patient simulation is particularly well suited for skills-oriented basic and advanced life support training in wilderness prehospital courses.45 This tool merges computer technology with fundamental behavior-based adult learning principles to deliver effective teaching. Students are both challenged and stimulated to high levels of performance. Information is delivered in a tangible, practical fashion with immediate reinforcement. Learners may repeat scenarios, make on-the-spot corrections of wrong decisions, and see immediate results. Simulation at this level is more efficient than both problem- and scenario-based teaching largely due to the high quality of feedback that learners receive as they observe the immediate consequences of their interventions.45

Evaluation of Teaching

Assessment of the teaching process is an integral part of completing the education cycle. It is hard to imagine how any course could flourish without a mechanism to self-evaluate and make periodic adjustments. This is part of what educators are accountable for when promising to deliver a product. Organizations that track, report, and maintain standards for the awarding of CME and CEU credit require this step to ensure that the quality of health care instruction is maintained at a high level. Evaluation is often viewed negatively by teaching staff. However, if done properly, it can take on a positive quality as a means to provide feedback. All curricula should evolve in ways that are responsive to students’ needs. Formal self-evaluation requires a method to organize this process. The main purposes of evaluation are as follows:51

Usefulness of the Results

Like any other assessment, the ideal evaluation is reliable, valid, acceptable, and inexpensive.51 A violation of any of these will decrease the usefulness of the instrument. A poorly designed or administered critique wastes valuable resources and time for both respondents and faculty. This lack of respect will transform the process into a meaningless exercise. So how does one ensure that the results will be useful? The most important aspect is the actual construction of the instrument itself (see later discussion). Next is to make students feel vested in the course so that thoughtful assessment has a purpose and comes naturally. This must be nurtured in the course design and should have already occurred before the critique forms are handed out on the last day. Attend to the principle of proximity. For lengthy courses, ensure that there is time scheduled and reminders given each day to fill out critique forms for each session. A short, overall evaluation of the course can be done at the end. Students may be in a hurry to depart after academic activities are over and evaluations are being completed. A common technique to ensure that each student completes an evaluation is to require that he or she turns in a form before receiving a graduation or training certificate.

What to Evaluate

Participants may be queried about anything that is relevant to the conduct of the course. However, consideration must be given to the actual usefulness of the information and the time it takes to complete the form. At a minimum, students should be given the opportunity to rate and add additional commentary on the following components:15

Program and Curriculum Development

Concepts and Models

Prideaux recently described a curriculum as “existing at three basic levels: what is planned for the students, what is delivered to the students, and what the students experience.” In practical application a curriculum should be easily communicated to learners and educators, should be open to critique and modification, and should be easily implemented. More specifically, it should contain four elements: content, teaching and learning strategies, assessment processes, and teaching evaluation methods. The process of curriculum design attempts to form these elements into a tangible, usable device.61

Numerous versions of curriculum design are in use throughout the United States and Europe. Many have been reported in the wilderness medicine literature.12,45,58–60,76 Steve Donelan has written extensively on the subject and offers the most detailed guidance available.15,19–23 Nearly all courses use a combination of techniques to deliver material to learners. A focus on outcomes is a common theme.

Steps in Designing a Curriculum

The success or failure of any educational experience goes far beyond a title. Simply using a wilderness medicine label may attract enthusiasts initially. However, failing to deliver a sound learning experience that is rooted in fundamental educational concepts, that leverages the most modern technology when applicable and practicable, and that is clinically useful will rapidly send would-be attendees looking elsewhere for ways to spend their valuable time and education dollars. The design of the curriculum lies at the heart of this issue. McGraw and Gluckman reported on the results of their efforts to bring wilderness medicine to undergraduate medical education at the University of Pennsylvania School of Medicine. A postcourse survey indicated that a large number (40%) of respondents found the course to be the best experience they had undergone in medical school.49 As Steve Donelan24 indicated in his commentary on their report, medical schools may have much to learn from these nontraditional courses, given the strength of their curricula and overall course design, quality of teaching, and relevance of the clinical information contained therein.

Desired Outcomes

The set of general educational objectives for the WPHEC curriculum proposed in 1991 by the Wilderness Medical Society (summarized later) offers an example of how to organize course objectives for this type of program.76 A learning needs assessment of the intended audience allows these to be rewritten in a more active tense using appropriate verbs to make them suitable for use as outcomes in any setting. Courses designed to provide certification or registration would address this requirement as well in the course objectives.

Planning for Continuing Medical Education

Educational experiences intended to assist practitioners at all levels of nearly all medical disciplines maintain currency, refresh eroded skills and knowledge, or add new skills and knowledge are vital to safety and viability across the health care industry. Despite the importance and use by all health care disciplines, there remains a relatively small body of evidence beyond tradition, anecdote, and expert opinion to support the use of any given educational technique or set of techniques over any another in the planning and delivery of CME.55 There are evidence-based guidelines produced by some specialty-oriented professional organizations based on the existing body of educational research. These attempt not only to elevate the effectiveness of CME but also to standardize training techniques within the discipline and inform the industry that has grown up to produce continuing education.50 The body of literature on which these guidelines are based is not large and reflects the tremendous difficulty inherent in studying education in a way that is based on outcomes and that allows for reliable cause-and-effect conclusions. It seems reasonable, however, to assert that continuing education for health care should adhere to fundamental principles of adult education already discussed. For example, augmenting a course based on a traditional lecture format by using multiple approaches to deliver information such as multimedia presentations or interactive, small-group, case-based discussion will enhance energy and improve learning. When practical to the setting, simulation is a preferable method to refresh, maintain, and learn new psychomotor skills.1,40,55

1 Accreditation Council for Continuing Medical Education (ACCME) Mission, http://www.accme.org/index.cfm/fa/about.home/about.cfm.

2 Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education (ACGME) Outcome Project, http://www.acgme.org/Outcome/.

3 Auerbach P. How to write a good and interesting manuscript [editorial]. J Wilderness Med. 1993;4:1.

4 Auerbach P. Continuing medical education: A wilderness of its own [editorial]. J Wilderness Med. 1994;5:248.

5 Barrows H, Tamblyn R. Problem-based learning: An approach to medical education. New York: Springer; 1980.

6 Barsuk J. Mastery learning of temporary hemodialysis catheter insertion by nephrology fellows using simulation technology and deliberate practice. Am J Kidney Dis. 2009;54:70.

7 Barsuk J. Simulation-based mastery learning reduces complications during central venous catheter insertion in a medical intensive care unit. Crit Care Med. 2009;37:2697.

8 Brookfield S. The skillful teacher. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1990.

9 Cate O, Snell L, Mann K, et al. Orienting teaching toward the learning environment. Acad Med. 2004;79:219.

10 Continuing education for health professionals. Writing objectives, Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. http://www.usuhs.mil/che/write_objective.htm.

11 Cook D. Virtual patients: A critical literature review and proposed next steps. Med Educ. 2009;43:303.

12 Cordes D, Rea D, Gerhauser R. Wilderness medicine: A clinical introduction for medical students. J Wilderness Med. 1992;3:367.

13 Davidson M. The 360 degrees evaluation. Clin Podiatr Med Surg. 2007;24:65.

14 Donelan S. Letter to the editor. J Wilderness Med. 1991;2:369.

15 Donelan S. Teaching emergency care skills. Wilderness Environ Med. 1999;10:125.

16 Donelan S. Testing emergency care skills. Wilderness Environ Med. 1999;10:261.

17 Donelan S. Classroom and reality: Lessons from real emergencies. Wilderness Environ Med. 2000;11:122.

18 Donelan S. Staging simulated accidents. Wilderness Environ Med. 2000;11:52.

19 Donelan S. Teaching patient assessment. Wilderness Environ Med. 2000;11:209.

20 Donelan S. Evaluating and improving your class. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001;12:134.

21 Donelan S. How to use textbooks, handouts, and visual aids. Wilderness Environ Med. 2001;12:42.

22 Donelan S. Explanation as a teaching technique. Wilderness Environ Med. 2003;14:194.

23 Donelan S. Mountaineering and mountain rescue. Wilderness Environ Med. 2004;15:44.

24 Donelan S. An introduction to the perceived benefits of a medical school course in wilderness medicine. Wilderness Environ Med. 2005;16:105.

25 Downer A, Pace A: Application of learning theory to health education. University of Washington Master of Public Health EDP faculty lecture handout; 2001-2002 academic year.

26 Forsyth D. Group dynamics. Pacific Grove, Calif: Brooks-Cole; 1990.

27 Gardner R. Simulation in obstetrics and gynecology. Obstet Gynecol Clin North Am. 2008;35:97.

28 Goldstein R, Zuckerman B. A perspective on 360-degree evaluations. J Pediatr. 2010;156:1.

29 Hay P, Katsikitis M. The expert in problem-based and case-based learning: Necessary or not? Med Educ. 2001;35:22.

30 Houghton W. The power of scenario. Wilderness Environ Med. 1997;8:127.

31 Hunt E. Simulation: Translation to improved team performance. Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;25:301.

32 Hutchinson L. Educational environment. BMJ. 2003;326:810.

33 Irby D. What clinical teachers in medicine need to know. Acad Med. 1994;69:333.

34 Irby D, Rakestraw P. Evaluating clinical teaching in medicine. J Med Educ. 1981;56:181.

35 Jaques D. ABC of learning and teaching in medicine: Teaching small groups. BMJ. 2003;326:492.

36 Johnson D, Johnson F. Joining together: Group theory and group skills. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1991.

37 Kash K. ACGME competencies in neurology: Web-based objective simulated computerized clinical encounters. Neurology. 2009;72:893.

38 Kaufman D. Applying educational theory in practice. BMJ. 2003;326:213.

39 Knowles M. Androgogy in action: Applying modern principles of adult learning. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1984.

40 Kokemueller P. Trends and developments in continuing medical education. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2007;40:1331.

41 Kolb D. Experiential learning: Experience as the source of learning and development. Old Tappan, NJ: Prentice-Hall; 1984.

42 Kromann C. The effect of testing on skills learning. Med Educ. 2009;43:21.

43 Krueger P, Neutens J, Bienstock J, et al. To the point: Reviews in medical education teaching techniques. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;191:408.

44 Lawry G, Schuldt S, Kreiter C, et al. Teaching a screening musculoskeletal examination: A randomized, controlled trial of different instructional methods. Acad Med. 1999;74:199.

45 Macias D, Rogers K, Alcock J. Development of a wilderness and travel medicine rotation in an academic setting. Wilderness Environ Med. 2004;15:136.

46 Mager R. Preparing instructional objectives: A critical tool in the development of effective instruction, ed 3. Atlanta: The Center for Effective Performance; 1997.

47 Marple B. Competency-based resident education. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2007;40:1215.

48 Maslow A. Motivation and personality. New York: Harper & Row; 1954.

49 McGraw D, Gluckman SJ. The perceived benefits of a medical school course in wilderness medicine. Wilderness Environ Med. 2005;16:106.

50 Moores L, Dellert E, Baumann M, et al. Executive summary: Effectiveness of continuing medical education: American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines. Chest. 2009;135:1s.

51 Morrison J. Evaluation. BMJ. 2003;326:385.

52 Nelson M. Wilderness medicine education [editorial]. J Wilderness Med. 1992;3:346.

53 Nikendei C. Integration of role-playing into technical skills training: A randomized controlled trial. Med Teach. 2007;29:956.

54 Nishisaki A. Does simulation improve patient safety? Self-efficacy, competence, operational performance, and patient safety. Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;25:225.

55 Norman G. The American College of Chest Physicians evidence-based educational guidelines for continuing medical education interventions. Chest. 2009;135:834.

56 Overstreet M. The use of simulation technology in the education of nursing students. Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;43:593.

57 Parvoti D. Virtual worlds and team training. Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;25:321.

58 Pattinson K, Matthews S. Climbing the education mountain: Designing the new diploma in mountain medicine for the United Kingdom. Wilderness Environ Med. 2004;15:44.

59 Peters P. Practical aspects in mountain medicine education. Wilderness Environ Med. 2000;11:262.

60 Peterson E, Snider W, Fahrenwald R. A model for wilderness medicine education in a family practice residency. Wilderness Environ Med. 2002;13:266.

61 Prideaux D. Curriculum design. BMJ. 2003;326:268.

62 Reed D. What is an hour-lecture worth? Am J Surg. 2008;195:379.

63 Schweinfurth J. Interactive instruction in otolaryngology resident education. Otolaryngol Clin North Am. 2007;40:1203.

64 Small S. Simulation applications for human factors and systems evaluation. Anesthesiol Clin. 2007;25:237.

65 Smee S. Skills based assessment. BMJ. 2003;326:703.

66 Steele D, Medder J, Turner P. A comparison of learning outcomes and attitudes in student- versus faculty-led problem-based learning: An experimental study. Med Educ. 2000;34:23.

67 Stern D, Williams B, Gill A, et al. Is there a relationship between attending physicians’ and residents’ teaching skills and students’ examination scores? Acad Med. 2000;75:1144.

68 Sweet R. Simulation and computer-animated devices: The new minimally invasive skills training paradigm. Urol Clin N Am. 2008;35:519.

69 Tuckman B. Developmental sequence of small groups. Psychol Bull. 1965;63:384.

70 Tuckman B, Jenson M. Stages of small group development revisited. Group and Organizational. Studies. 1977;2:419.

71 Vella J. Learning to listen, learning to teach: The power of dialogue in educating adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1994.

72 Vella J. How do they know they know?. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1995.

73 Vella J. Training through dialogue: Promoting effective learning and change with adults. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass; 1995.

74 Weiner E. Supporting the integration of technology into contemporary nursing education. Nurs Clin North Am. 2008;43:497.

75 Whitman N. The physician as teacher, ed 2. Salt Lake City, Utah: Whitman Associates; 1997.

76 Wilderness Medical Society Pre-hospital Committee. Wilderness pre-hospital emergency care curriculum. J Wilderness Med. 1991;2:80.

APPENDIX A Wilderness Medicine Educational Organizations, Resources, and Programs

Professional Societies

A number of U.S. and international societies exist that have guided establishment of academic standards in wilderness medicine education (Boxes 105-8 and 105-9). These organizations typically sponsor CME events through large, sometimes international, meetings to further education, research, and international cooperation and sharing of knowledge. The Wilderness Medical Society (WMS) and the International Society for Mountain Medicine (ISMM) both sponsor educational activities and publish their own peer-reviewed journals (Wilderness and Environmental Medicine, High Altitude Medicine and Biology). The WMS, for example, hosts CME events and offers fellowship training to members through its Academy of Wilderness Medicine. Several professional societies, including the American College of Emergency Physicians and the Society for Academic Emergency Medicine possess wilderness medicine interest groups or chapters. Other organizations, such as the Divers Alert Network or the National Ski Patrol, focus on specific content areas.

BOX 105-8 United States–Based Professional Societies

| Aerospace Medical Association | http://www.asma.org |

| American Alpine Club | http://www.americanalpineclub.org |

| American College of Emergency Physicians (Wilderness Medicine Chapter) | http://www.acep.org |

| Appalachian Center for Wilderness Medicine | http://www.appwildmed.org |

| Divers Alert Network (DAN) | http://www.diversalertnetwork.org |

| Institute for Altitude Medicine | http://www.altitudemedicine.org |

| International Society for Mountain Medicine | http://www.ismmed.org |

| International Society of Travel Medicine | http://www.istm.org |

| Mountain Rescue Association (MRA) | http://www.mra.org |

| National Association for Search and Rescue (NASAR) | http://www.nasar.org |

| National Ski Patrol | http://www.nsp.org |

| Society for Academic Emergency Medicine (Wilderness Medicine Interest Group) | http://www.saem.org |

| Undersea and Hyperbaric Medical Society | http://www.uhms.org |

| Wilderness Medical Society (WMS) | http://www.wms.org |

BOX 105-9 International Professional Societies

| Argentine Mountain Medicine Society | http://www.samm.org.ar (Spanish) |

| Austrian Society for Mountain and High Altitude Medicine | http://www.alpinmedizin.org (German) |

| German Society for Mountain and Expedition Medicine | http://www.bexmed.de (German) |

| Himalayan Rescue Association of Nepal | http://www.himalayanrescue.org |

| International Commission for Alpine Rescue (ICAR) | http://www.ikar-cisa.org |

| International Mountaineering and Climbing Federation (UIAA) | http://www.theuiaa.org |

| Mountain Medicine Society of Nepal | http://www.mmsn.org.np |

| Swiss Mountain Medicine Society | http://www.mountainmedicine.ch (German) |

Opportunities for Medical Students and Physicians

Medical Students

Opportunities for medical student education have increased tremendously. Although students are free to pursue WFA and WFR courses as described later, many seek formal electives for educational credit through medical schools. These electives continue to grow, typically require a 2- to 4-week commitment in the third or fourth year, and may result in WFR or other certification. The majority of these experiences incorporate classroom instruction with some form of outdoor experience with problem- or case-based learning. Several of these electives are based in urban locations and transition to backcountry or resource-poor settings for experience-based teaching and simulation. The WMS has a well-established month-long course in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in association with the Uniformed Services University of the Health Sciences. In addition, the WMS sponsors student interest groups to help foster educational activities and events. Although students are free to attend CME events in wilderness medicine, several conferences exist specifically for medical students. Box 105-10 lists some well-established programs with links to their websites.

BOX 105-10 Medical Student Electives

HAEMR, Harvard Affiliated Emergency Medicine Residency; NOLS, National Outdoor Leadership School.

Residents

Several organizations offer elective time to residents, primarily in family and emergency medicine (Box 105-11). These electives incorporate a variety of EMS, search and rescue training, and international experiences and typically require a 2- to 4-week commitment. Many elective experiences integrate learners from all disciplines and levels of medical education.

BOX 105-11 Resident Electives

| Grand Canyon Clinic | http://www.nps.org/grca |

| Grand Teton National Park | http://www.wildmedconsulting.com |

| Madigan Army Medical Center | http://www.fieldmedicine.net |

| Medical Clinic of Big Sky | http://www.docsky.us |

| Stanford University | http://emed.Stanford.edu/fellowships/wilderness.html |

| Telluride Medical Center, Institute for Altitude Medicine | http://www.telluridemedicalcenter.org |

| University of California San Francisco-Fresno | http://www.fresno.ucsf.edu/em/wilderness.html |

| University of Virginia | http://www.healthsystem.virginia.edu/internet/medtox/education/Wilderness/home.cfm |

Postgraduate Training

Non-ACGME fellowships exist for graduates of emergency medicine residencies (Box 105-12). These fellowships typically involve a mixture of traditional emergency medicine clinical work with nonclinical time devoted to wilderness training. The WMS offers Fellowship of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine (FAWM) certification for physicians and members. FAWM candidates obtain credits through attending CME events and documenting field experience. Physicians can also pursue an International Diploma of Mountain Medicine certified by the Union Internationale des Associations d’Alpinisme (UIAA), Internationale Kommission für Alpines Rettungswesen (IKAR), and ISMM.

BOX 105-12 Fellowship and Training Opportunities for Physicians

| International Mountaineering and Climbing Federation (UIAA) | http://www.theuiaa.org/mountain_medicine.html |

| Loma Linda University School of Medicine | http://www.lomalindahealth.org/medical-center/our-services/emergency |

| Massachusetts General Hospital | http://www.mgh.harvard.edu/education/fellowship.aspx?id=94# |

| Stanford University Medical Center | http://www.emed.standford.edu/fellowships/wilderness.html |

| University of California San Francisco-Fresno | http://www.fresno.ucsf.edu/em |

| University of Utah | http://www.utahhealthsciences.net/pageview.aspx?id=17053 |

| Wilderness Medical Society Academy of Wilderness Medicine | http://www.wms.org/fawm |

Certification Programs

Wilderness medicine certification programs exist in a variety of forms for a diverse audience. Laypeople, first responders, physicians, allied health professionals, and others may find courses for their particular skill set and interest. No national or international governing body enforces standards for these certification programs. However, there are a number of widely recognized curricula, such as the National Practice Guidelines for Wilderness Emergency Care published by the Wilderness Medical Society. Most of these certifications rely heavily on skills-based testing and mirror more traditional training programs such as Basic Life Support and Advanced Cardiac Life Support. Certifications are typically valid for 2 to 3 years with a trend toward 2 years. Some have argued for development of standardized, national curricula for wilderness medicine programs. However, the proprietary nature of curricula and certifications may be an impediment to this process. Box 105-13 lists certification programs and Box 105-14 lists some of the major organizations that provide training.

BOX 105-13 Certification Types

| Audience | Average Time of Instruction | |

|---|---|---|

| Wilderness First Aid (WFA) | Open | 16-24 hours |

| Basic Wilderness Life Support (BWLS) | Open | 16 hours |

| Introduction to Search and Rescue (ISAR) | Open | 16 hours |

| Advanced Search and Rescue (ADSAR) | Open | 19 hours |

| Wilderness Advanced First Aid (WAFA) | Open | 36 hours |

| Advanced Wilderness First Aid (AWFA) | Open | 48 hours |

| Wilderness First Responder (WFR) | Open | 64-80 hours |

| Wilderness Emergency Medical Technician (WEMT) | EMTs | 170+ hours |

| Advanced Wilderness Life Support (AWLS) | Medical professionals | 36 hours |

| Wilderness Advanced Life Support (WALS) | Medical professionals | 36 hours |

| Remote Medicine for the Advanced Providers (RMAP) | Medical professionals | 44 hours |

| Diploma in Mountain Medicine (DiMM) | Medical professionals | 100 hours |

| Fellowship of the Academy of Wilderness Medicine (FAWM) | WMS members | 100 credit hours |

EMT, Emergency medical technician; WMS, Wilderness Medical Society.

BOX 105-14 Educational Organizations