Wilderness Medical Kits

Organizing the medical equipment for an expedition requires an enormous amount of planning and forethought. No matter how much equipment is hauled in, one cannot possibly prepare for every conceivable illness or accident. The variables on any expedition or wilderness excursion are complex, making generic advice on “what to take” difficult without an operational context. Major considerations should include the following:

1. Environmental extremes of the trip (e.g., arctic, valtitude, tropical, desert)

2. Time of year (e.g., climatic conditions) and disease conditions

4. Medical expertise of the intended user

5. Medical expertise of other trip members

6. Total number of expedition members, including ancillary staff (e.g., porters, local guides, expedition staff)

8. Age and sex of participants

9. Known preexisting medical problems of the group

10. Distance from definitive medical care

11. Availability of communications (e.g., cell phones, radios, satellite phones, telemedicine capability)

12. Availability and time frame of rescue

Medical Kits

1. The wilderness medical kit should be well organized in a protective and convenient carrying case or pouch. For backpacking, trekking, or hiking, a nylon or Cordura organizer bag is optimal.

2. Newer-generation bags with clear, vinyl compartments have proved superior to mesh-covered pockets for protecting the components from the environment.

3. Clear vinyl protects the components from dirt, moisture, and insects and keeps the items from falling out when the kit is turned on its side or upside down.

4. For aquatic environments, store the kit in a waterproof dry bag or watertight container, such as a Pelican or OtterBox case. Inside, seal items in resealable plastic bags with “zippers” (e.g., Ziploc) because moisture will invariably make its way into any container.

5. Some medicines may need to be stored outside of the main kit to ensure protection from extreme temperatures. Capsules and suppositories melt when exposed to temperatures above 37° C (98.6° F), and many liquid medicines (e.g., insulin) become useless after freezing.

6. Commercially produced kits are available, either prestocked or unfilled.

7. Fragile items and injectable medications can be carried in small, portable plastic containers (e.g., Tupperware).

Organization

Medical supplies can be divided into four categories: personal kits, group kit, medial devices and medications, and specialized equipment for particular environmental and recreational hazards. The size and complexity of the medical kit depends on the amount of equipment required, duration of trip, and number of team members. For smaller trips, a single person can carry a moderately sized, comprehensive medical kit for the group. For longer expeditions, or expeditions with many participants, larger kits may be divided into several smaller kits for individual members to carry.

Personal Kit

Each trip member should be responsible for and carry a personal kit. This avoids constant disruption of the group kit, which can play havoc over time. Personal kits are variable but should include commonly used items. A personal kit might contain the following:

Comprehensive Group Medical Kit

The group medical kit should be carefully constructed to meet the likely needs of the entire group. The contents of the group medical kit will vary greatly, depending on the environment, risks and hazards, and skill level of the medical provider. In general, the group kit should contain the following:

1. Medical guidebooks, personal digital assistant, and Internet sources if available

2. Comprehensive first-aid kit (Box 61-1)

3. Appropriate prescription medications for general illness (Tables 61-1 and 61-2)

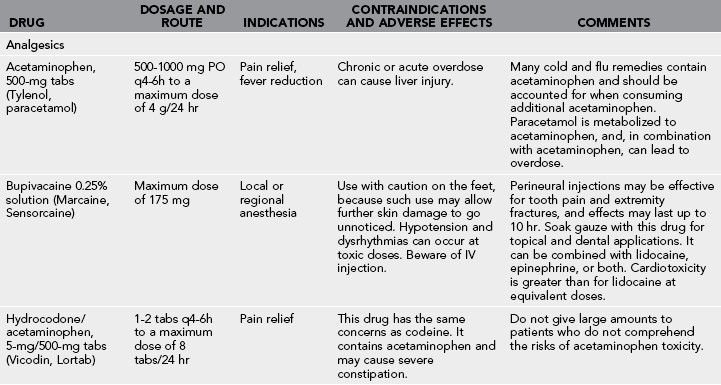

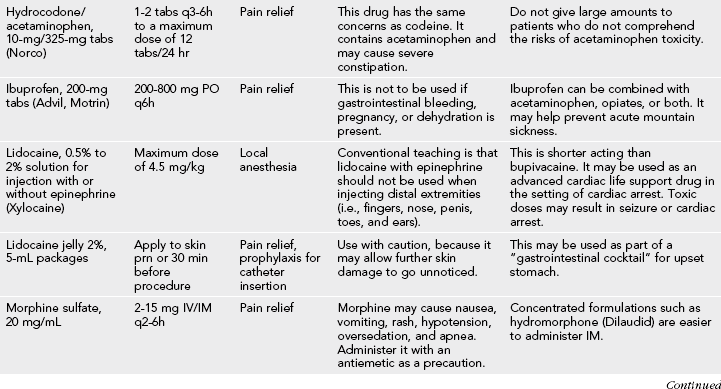

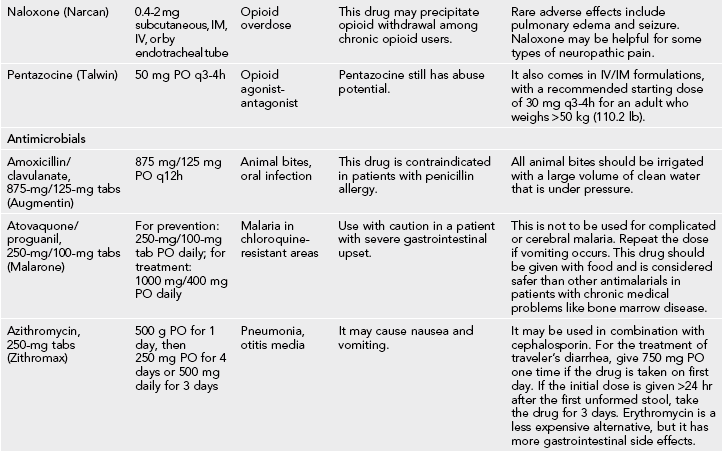

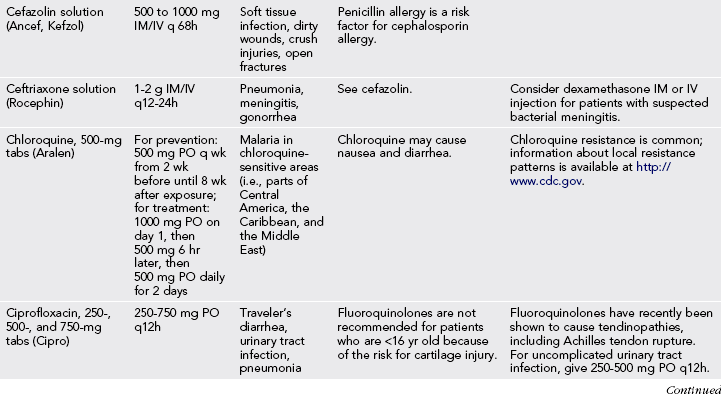

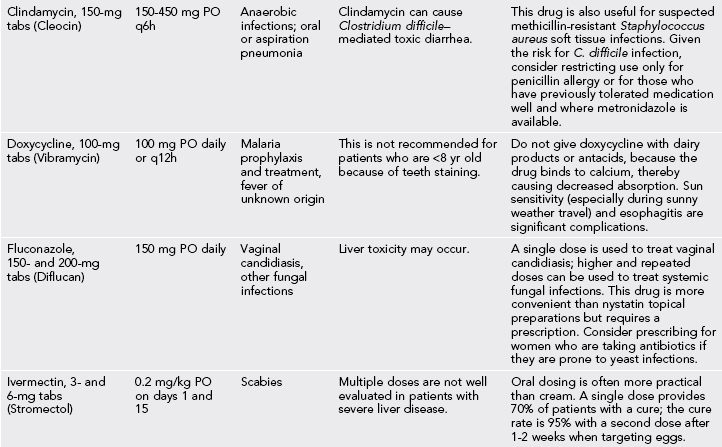

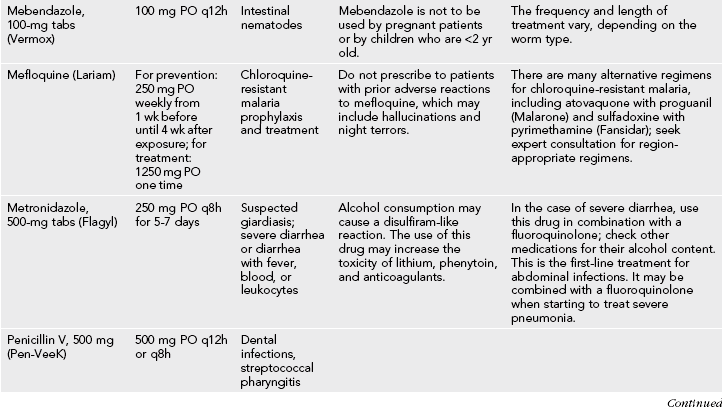

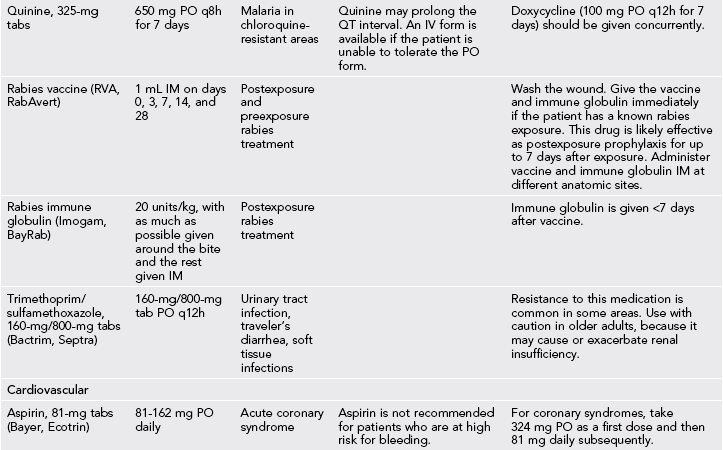

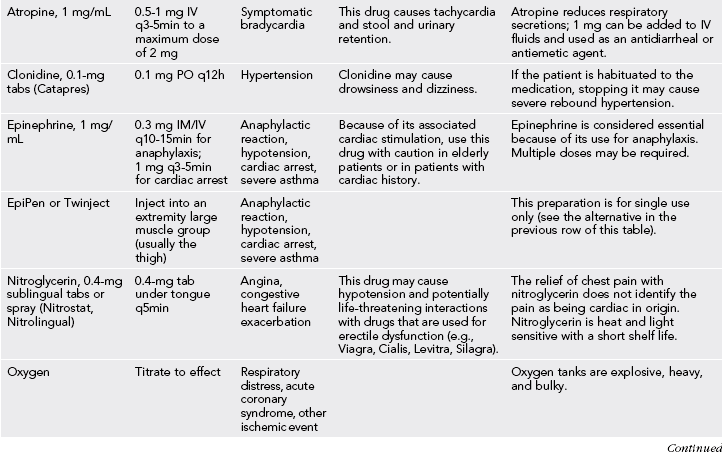

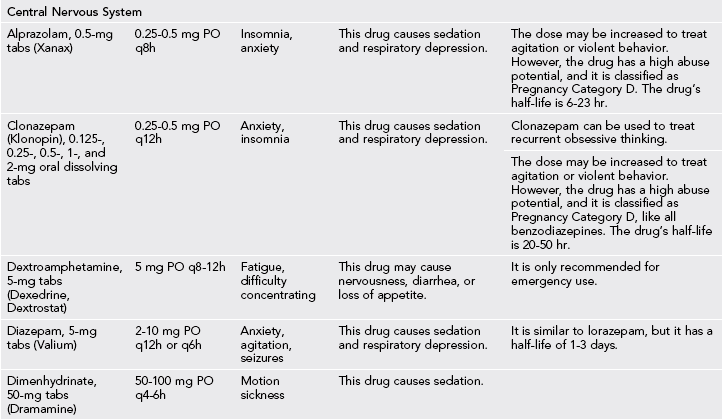

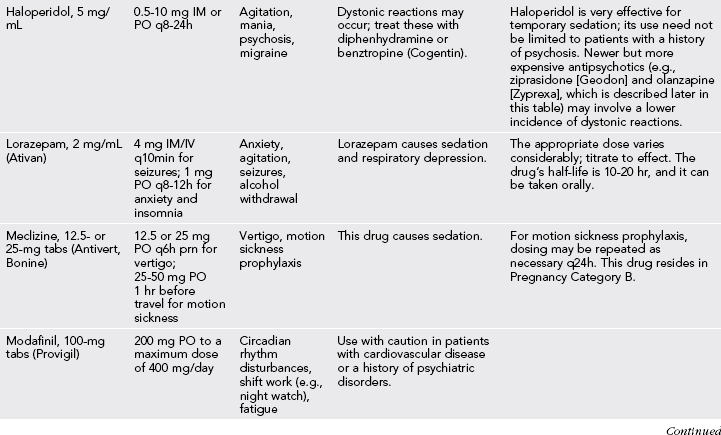

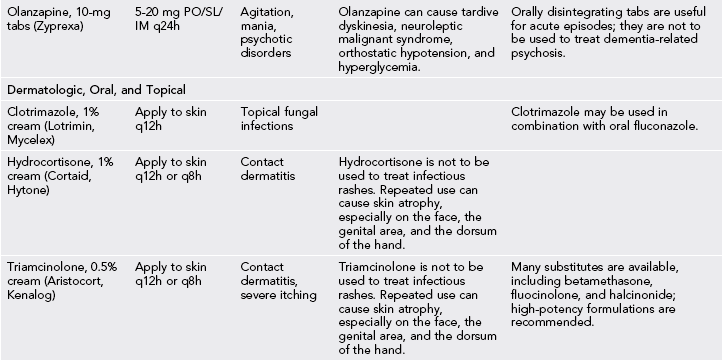

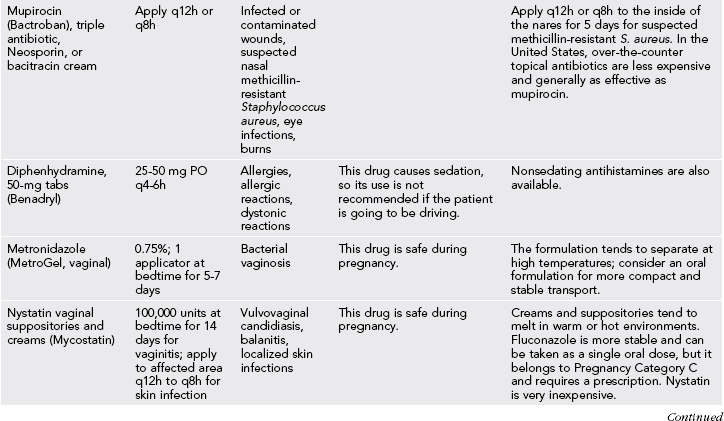

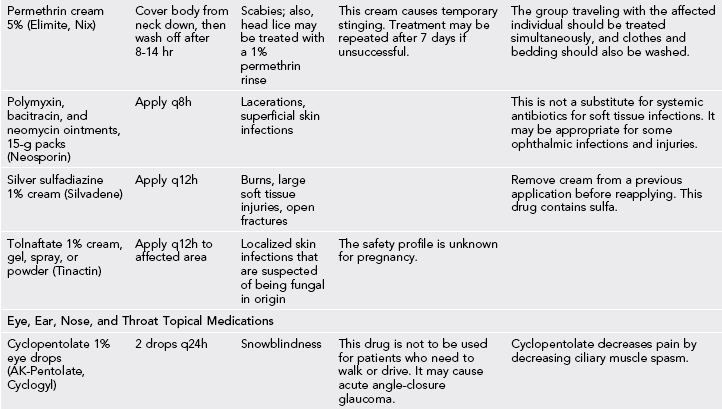

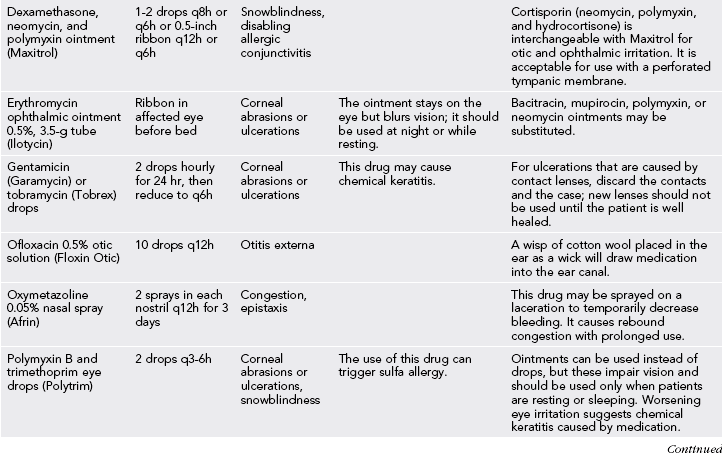

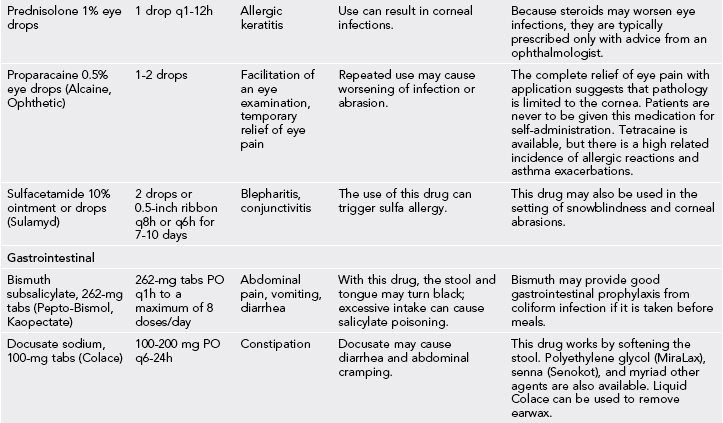

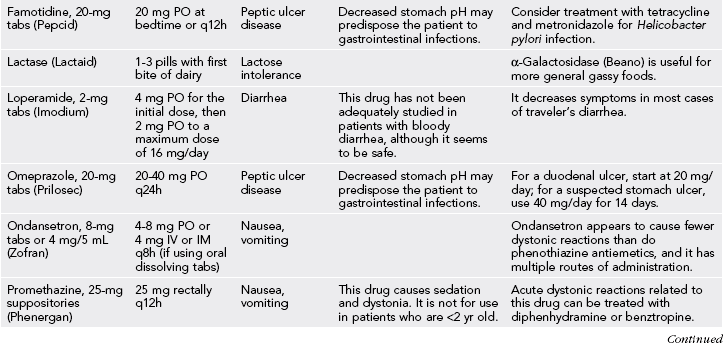

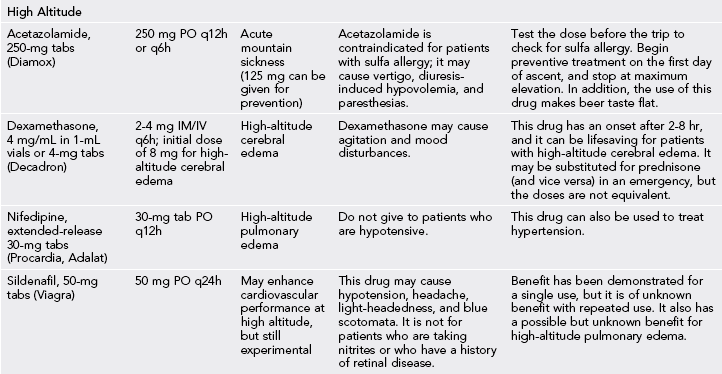

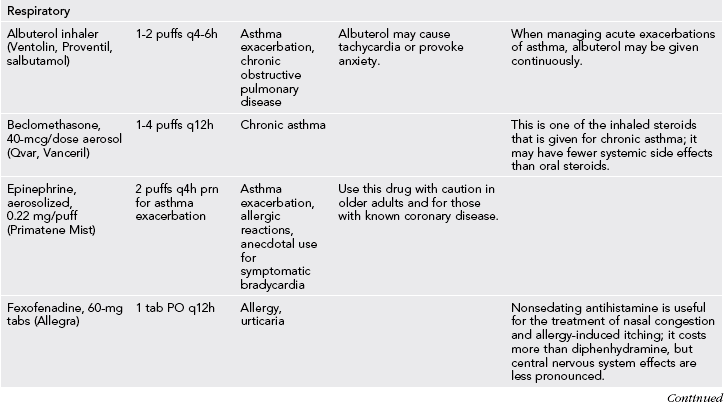

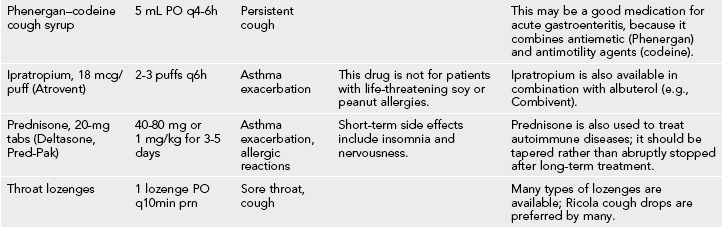

Table 61-1

Selected Medications for Wilderness Travel

IM, intramuscular; IV, intravenous; PO, by mouth; prn, as needed; q, every; SL, sublingual.

Table 61-2

Indications for Antibiotic Treatment in Wilderness Travelers

| Traveler’s diarrhea: sensitivity to various antibiotics varies based on region and should be researched before departure (e.g., there is high resistance to ciprofloxacin by Campylobacter species in the Himalayan region) | Ciprofloxacin, 750 mg PO × 1, or azithromycin, 1 g PO × 1, if diarrhea is being treated within the first 24 hr. If treating diarrhea of >24 hr duration, then use azithromycin, 500 mg PO daily × 3 days, or ciprofloxacin, 750 mg PO q12h × 3 days. Antimotility agents should not be given in the setting of dysentery, fever, or other abnormal vital signs. |

| Diarrhea (suspected giardiasis) | Metronidazole, 250 mg PO q8h × 5 days |

| Diarrhea in pregnant women or children | Trimethoprim/sulfamethoxazole DS, 1 tab PO q12h × 3 days |

| Fungal infections (e.g., yeast vaginitis) | Fluconazole, 150 mg PO × 1 |

| Lacerations from animal bites | Amoxicillin/clavulanic acid, 875/125 mg PO q12h × 3-5 days (this recommendation is controversial) |

| Lacerations with gross contamination or bone, tendon, or cartilage exposure | Cephalexin, 500 mg PO q6h × 3-5 days |

| Pneumonia | Doxycycline, 100 mg PO q12h × 7 days, or azithromycin, 500 mg PO on day 1 then 250 mg daily on days 2-5, or levofloxacin, 500 mg PO daily, or moxifloxacin, 400 mg PO daily |

| Sexually transmitted urethritis | Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg PO × 1 or cefixime, mg; and azithromycin, 1 g PO × 1, or doxycycline, 100 mg PO q12h × 7 days |

| Urinary tract infections | Ciprofloxacin, 250-500 mg PO q12h × 3 days |

| Appendicitis or other intra-abdominal infection | Ciprofloxacin, 500 mg PO q12h and metronidazole, 500 mg PO q6h |

4. Devices and medications for the medically trained (Box 61-2), including portable diagnostic instruments for wilderness travel (Table 61-3)

Table 61-3

Portable Diagnostic Instruments for Wilderness Travel

| DEVICE | INDICATION |

| Urine pregnancy test (e.g., Baby Check, Midstream, SureStep, or one of many other generic and name brands) | Essential for evaluation of abdominal pain in women of childbearing age; a positive pregnancy test result raises the possibility of ectopic pregnancy, and immediate evacuation should be considered |

| Glucometer (e.g., Therasense) | Useful for routine diabetes management and for evaluation of ill-appearing diabetic individuals who may have a too-low or too-high serum glucose level |

| Fluorescein dye strips and fluorescent light sticks | Evaluate for corneal abrasions; if present, the eye should be flushed, the lid flipped to search for a foreign body, and the patient treated with topical antibiotic drops or ointment |

| Hemoccult cards and developer | Patients with traveler’s diarrhea and bloody stool should not be given loperamide or another antiperistaltic agent |

| Low-reading (hypothermia) thermometer (e.g., Adtemp 419 digital) | Essential for evaluation of hot or cold patients, particularly those for whom alternative diagnoses are being considered |

| Sphygmomanometer (blood pressure cuff) | Useful for accurate measurement of blood pressure, particularly in trauma patients and patients with tachycardia or altered mental status; may be used as an adjustable tourniquet |

| Stethoscope | Useful for auscultation of the abdomen and chest, particularly to evaluate for the presence of wheezing, pulmonary edema, or pneumothorax |

| Urine test strips (e.g., Clinitek) | Useful for evaluation of abdominal pain, urinary symptoms, and hyperglycemia; hyperglycemia and the presence of urine ketones suggest diabetic ketoacidosis |

| Chronometer with second hand | Useful for accurate measurement of heart rate and respiratory rate; also important when planning evacuations |

| Magnifying glass | For foreign-body identification and removal |

| Pulse oximeter (e.g., Respironics, Nonin) | Provides finger-sized, digital, light-emitting diode readouts for estimating tissue oxygenation |

| End-tidal carbon dioxide detector (e.g., Nellcor) | Colorimetric devices are available to help with confirmation of endotracheal tube placement; quantitative devices are coming to the market |

5. Indicated equipment based on recreational and environmental hazards (Box 61-3)

General Guidelines for Expedition Drugs

1. When possible, choose medications with low side-effect profiles.

2. Choose medications with few contraindications (e.g., amoxicillin/clavulanate is contraindicated in penicillin-allergic patients).

3. When possible, choose medications that have multiple indications (e.g., drugs like diphenhydramine and prednisone have many uses).

4. Choose medications that have favorable dosing schedules (e.g., once a day). Compliance will markedly improve, and the weight and volume of the medical kit will be greatly reduced.

5. Carry enough medications to treat multiple persons over the course of the expedition.

Antibiotics

Prepare for the common infectious disease problems listed in Table 61-2, and by selecting appropriate antibiotics.

Wilderness Medications

1. When assembling medicine kits for a group, always include copies of the manufacturer’s package insert with each medicine.

2. Table 61-1 lists commonly carried over-the-counter and prescription medications. This list is not comprehensive but provides options from which medical designees can choose based on their group needs.

3. Many medications (e.g., atropine, epinephrine, dexamethasone, nifedipine, nitroglycerin) have significant systemic effects. Administration of these medications is usually directly managed or guided by physicians, nurses acting under the direction of a physician, or designated medical providers with appropriate training.

4. Many emergencies can be managed by either oral or transdermal application of medicines.

5. IV medications are temperature sensitive and fragile, expire quickly, and require monitoring of vital signs because of potency and immediate onset of action.

6. Opioid analgesics should be used to treat pain only if mild analgesics (e.g., ibuprofen, acetaminophen) are inadequate, mental status is clear, and respiratory distress is not present (unless it is due solely to discomfort).

7. Any expedition carrying opioids should also carry a reversal agent (e.g., naloxone).

8. Whenever possible, medicines should be purchased as tablets rather than capsules because of the tendency of capsules to break apart or dissolve.

9. Under extremes of temperature, creams may become unusable; in such environments, oral medications are preferred.

10. Purchasing medications on arrival may be necessary and save money. Many medications that require prescriptions for purchase in industrialized countries, including opioids, are available over-the-counter in developing countries.

11. Many international medications do not contain the desired active ingredient or are adulterated with dangerous compounds. Travelers should make every effort to obtain medications from a reliable source.

[/level-membership-for-emergency-medicine-category]