Chapter 112 Wilderness Management and Preservation

In the United States and several countries around the world, the word wilderness is associated with a legal definition for places that are legislatively protected.10 The places selected and designated for protection follow certain general guidelines, and this political process is influenced by very strong and diverse groups of stakeholders and the general public. The management objectives for these areas include a variety of values, from preservation of the ecologic conditions and processes to human use and enjoyment (Figure 112-1). Although there is widespread public support for wilderness, there are divergent and polarized viewpoints on how to define wilderness, ranging from extreme protectionists who believe that humans have no place in wilderness to the utilitarian interests that hold that wilderness is a setting for economic development for recreation and tourism activities.

Although there are a variety of definitions of wilderness, the United States has a legal definition of wilderness, albeit somewhat vague, that is the basis for the creation of the National Wilderness Preservation System (NWPS). By 2010, the NWPS included more than 790 management units and more than 109 million acres of publicly owned lands managed by four federal agencies. The purpose of this chapter is to outline the legal designation, management, and preservation of wilderness areas in the United States.5

Historical Development of the Wilderness Concept

The term wilderness historically was used to describe places that were untamed and not under control of humans, whereas civilization was the place of human control.5,12 Areas of civilization that were cultivated and heavily influenced by human activities often bordered or were surrounded by areas that had little human influence. As the population of the world has grown and more land area has come under human influence, wilderness has been lost to the point that it is now scarce in many areas of the world.

There are few places that are not now, or have not been at one time, under human control, habitation, cultivation, or influence. A gradient of human influence and impact exists from urban centers and rural areas to some wild country (e.g., wilderness) that has little or no human influence (Figure 112-2). The so-called human footprint on the world is large and extending rapidly with population growth, road building, food production, power generation, industrialization, and human habitation.14 Some identifiable “last of the wild places” exists on each continent and might continue to do so with careful conservation of resources and protection worldwide of some remaining representative or remnant areas of each ecologic community type.14

Wilderness Legislation and Policy in the United States

The concept gradually evolved that legislative protection was needed to create a more permanent and coordinated national system for wilderness preservation and management. From 1956 to 1964, more than 50 versions of a wilderness bill were introduced in Congress, heavily debated, supported, and challenged by different interest groups. Political compromises were deemed necessary to finally get a wilderness bill passed into legislation, and so certain human activities were permitted in some areas, even though they would be nonconforming with the intent of the wilderness legislation.5,15 These included activities such as mining, grazing, aircraft landings, and water resources development.

In 1964, the U.S. Congress passed The Wilderness Act (U.S. Public Law 88-577).18 This legislation created the NWPS and was heralded by the environmental community and the general public as one of the most important pieces of conservation legislation in U.S. history.15 Scott comments16 that “before there was a Wilderness Act, wilderness was, at best, an afterthought. Only the U.S. Forest Service had actually delineated wilderness areas, propelled by visionaries within its own ranks.”

The Wilderness Act18 defines a broad statement of policy for designating wilderness under the Act and recognizes the need to set aside significant natural areas for present and future generations because of the rapid loss of such resources:

Section 2c of The Wilderness Act18 includes an important and often-quoted definition of wilderness that has led to much controversy and debate because although it is poetic in form, it has left room for interpretation, especially during legal hearings and court cases in the 40 years since its passage:

One of the conditions refers to “outstanding opportunities for solitude or a primitive and unconfined type of recreation”; that phrase is often referred to as the guiding principle for recreation and visitor management. A careful reading of the definition of wilderness makes it clear that preservation is the overall principle and reason for designating an area “wilderness.” Certain types and amounts of recreation are permitted, provided the area is “protected and managed so as to preserve its natural conditions.” This is an important principle to keep in mind when discussing recreation use and management (Figure 112-3), especially when it relates to primitive facilities and trails, backcountry travel, recreational equipment (e.g., removable climbing gear, backpacking stoves), and management interventions.

Creation of the NWPS with the Wilderness Act in 1964 was just the beginning of legislative designations. By 2009, there were more than 170 different laws passed by the U.S. Congress designating new areas or adding acreage to existing areas.5 As Hendee and Dawson9 note, in addition to the Wilderness Act, 40 years of subsequent legislation have clarified congressional intent to protect and manage our nation’s wildest remaining lands as wilderness and has expanded the NWPS…. It is hard to identify any natural resource issue—or any issue—for which Congress has so consistently and so often confirmed their intent as they have with wilderness.

The initial designation of 9.1 million acres of wilderness was followed by congressional designations in 32 of the 45 years between 1964 and 2009 to add additional acres and units to the NWPS (Table 112-1). The largest single increase was the addition of approximately 56 million acres in Alaska under the Alaska National Interest Lands Conservation Act of 1980 (Public Law 96-487).

TABLE 112-1 The Acreage of Wilderness Designated in 1964 at the Creation of the National Wilderness Preservation System and in 5-Year Intervals through 2010

| Year | Acreage |

|---|---|

| 1964 | 9,139,721 |

| 1966-1970 | 1,153,382 |

| 1971-1975 | 2,612,902 |

| 1976-1980 | 68,027,642 |

| 1981-1985 | 8,563,271 |

| 1986-1990 | 5,560,032 |

| 1991-1995 | 8,772,384 |

| 1996-2000 | 1,119,621 |

| 2001-2005 | 1,353,607 |

| 2006-2010 | 3,199,777 |

| Total | 109,502,248 |

From http://www.wilderness.net.

Many proposals for additional units and acreage are still being brought before Congress and its committees. Several authors and organizations have predicted that more acreage will be added to the NWPS in coming decades, but the estimated amount of those additions varies widely.5,15 Scott,16 a historian of wilderness policy and legislation, offers the observation that “however much wilderness Americans may choose to designate through their elected representatives, future generations are likely to judge that we preserved too little, rather than too much.”

Wilderness Stewardship Philosophy

Some management of wilderness resources and experiences is necessary as visitor use increases and surrounding land management and use affect the wilderness area. The idea that we need management in an area that was intended to be free of the influences of modern human activities may appear paradoxic. However, wilderness stewardship is the management of human uses of wilderness and internal and external influences on wilderness to protect and preserve an area’s solitude and naturalness, including natural processes and conditions. Hendee and Dawson9 highlight the wilderness stewardship philosophy for managers:

Potential Threats to Wilderness

Designating an area as wilderness is just the first step and must be followed by stewardship to maintain those areas that represent all that is left of many ecosystems, as well as natural landscapes that have not been cultivated, mined, developed, urbanized, or otherwise heavily altered by human activities. Numerous types of internal and external conditions, influences, and changes threaten wilderness resources and values, now and in the future.9 Three examples of categories of threats are summarized here to highlight the concern about the future sustainability of wilderness conditions and processes.

Dawson and Hendee5 identified 19 categories of internal and external threats as the change agents that affect wilderness conditions and values:

Wilderness Management Agencies in the United States

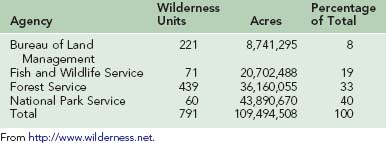

The NWPS included more than 790 units managed by four federal agencies and totaled more than 109 million acres of publicly owned lands by 2010 (Table 112-2). The four federal agencies administering the NWPS are the National Park Service (NPS), Bureau of Land Management (BLM), Fish and Wildlife Service (FWS) in the Department of Interior, and the Forest Service (FS) in the Department of Agriculture. The NPS has the greatest total area of wilderness at 43.8 million acres and the fewest units for a federal agency; the largest area in the NWPS, Wrangell-St. Elias Wilderness (>9 million acres) in Alaska, is under NPS management. The FS has the largest number of wilderness units to manage and approximately one-third of the total NWPS acreage. The FWS manages 19% of the NWPS area, including the smallest unit in the system, 5-acre Pelican Island Wilderness in Florida. The BLM has significant acreage in some of the desert ecosystems of the west and manages many smaller units in its 8% of the NWPS.

Distribution of Wilderness in the United States

The 109-million-acre NWPS represents just over 4.5% of the U.S. land area, in contrast to the more than 6% of total acreage in urban and suburban land area or more than 20% of the total in agricultural cropland.9 The NWPS is an attempt to designate wilderness areas that would represent the different geographic regions and ecosystems of the United States. The representation of ecosystems is not complete (<50% of types are represented), and it is more effective for some arid lands and mountain ecosystems of the west than for coastal lowlands, grasslands, and eastern hardwood forests.9

Forty-four of the states have federally designated wilderness, ranging from a 77-acre island wilderness area in Ohio to more than 57 million acres in the state of Alaska. The six states without federally designated wilderness are in the midwestern or northeastern United States. When the number of acres of designated wilderness in each state or region is compared with the total land area and total population, the pattern is an uneven distribution favoring the western United States.5 Less than 5% of the NWPS is located in the eastern United States, where more than one-half of the population resides on over 40% of the U.S. land area. The Pacific and mountain regions of the western United States have approximately 22% of the population and more than 95% of the NWPS. The greatest disparity is that Alaska has more than one-half of the land area of the NWPS and less than 1% of the U.S. population.

Whereas the NWPS is based on the Wilderness Act of 1964 and federal land ownership, there are also 12 states that have designated state wilderness programs or areas on state-owned lands since the 1970s.13 Most notable are 22 New York State wilderness areas (1.2 million acres in the Adirondack and Catskill Forest Preserves) and five Alaska state wilderness areas (1.1 million acres). The twelve states with wilderness programs or areas protect more than 3.2 million acres.13 These are managed by the state land managing agencies and are not parts of the NWPS. Many states have legislation and management programs modeled after the federal Wilderness Act.

The NWPS is extensive and complex geographically and is often difficult for visitors to locate because it is generally shown on agency maps only as part of overall public land holdings. For example, the Boundary Waters Canoe Area Wilderness in Minnesota is part of the Superior National Forest. A very helpful source to see the geographic distribution and location of the units in the NWPS is available at http://www.wilderness.net and is provided by the Wilderness Institute at The University of Montana’s College of Forestry and Conservation, the Arthur Carhart National Wilderness Training Center, and the Aldo Leopold Wilderness Research Institute. This website also links to the managing federal agency, the wilderness area’s legislative history, and visitor information sources.

Wilderness Values and Public Perceptions

The American public is strongly supportive of wilderness designation and the NWPS.1,3,4 Scott16 reported a summary of seven different surveys in the United States from 1999 through 2002 that showed 48% to 81% of respondents supported designating more wilderness land in the United States into the NWPS.

Although wilderness means something different to everyone, four central themes have consistently emerged: experiential, the direct value of the wilderness experience; the value of wilderness as a scientific resource and environmental baseline; the symbolic and spiritual values of wilderness to the nation and the world; and the value of wilderness as a commodity or place that generates direct and indirect economic benefits.5

National surveys in 1994 and 2000 reported4 that more than 50% of the public indicated that 12 of 13 wilderness values were very or extremely important to them (Table 112-3). The 1994 to 2000 surveys showed a trend to increase the percentage for all 13 values, indicating a higher level of value.3,4 The nonuse values tended to dominate the higher average value scores (scale ranged from “not important” to “extremely important”), with the highest value for protecting water quality and air quality. Strong support for the value of income for tourism industry use on wilderness lands tended to be reported by less than 30% of the respondents.

TABLE 112-3 Percentage of Americans (>16 Years of Age) Indicating a Response of Very or Extremely Important for 13 Wilderness Values

| Wilderness Value | Percentage |

|---|---|

| Protecting water quality | 93.1 |

| Protecting air quality | 92.3 |

| Protection of wildlife habitat | 87.8 |

| For future generations | 87.0 |

| Protection for endangered species | 82.7 |

| Preserving ecosystems | 80.0 |

| Future option to visit | 75.1 |

| Just knowing it exists | 74.6 |

| Scenic beauty | 74.0 |

| Recreational opportunities | 64.9 |

| For scientific study | 57.5 |

| Providing spiritual inspiration | 56.5 |

| Income for tourism industry | 29.7 |

From Cordell HK, Tarrant MA, Green GT: Is the public viewpoint of wilderness shifting? Int J Wilderness 9:27, 2003, with permission.

Western U.S. residents were somewhat more often aware of the NWPS than were easterners (60% versus 56%); conversely, eastern residents more often reported there was not enough land in the NWPS than did westerners (53% versus 48%).4 Metropolitan and urban residents more often reported there was not enough land in the NWPS than did rural residents (54% versus 44%).4

Wilderness Visitors

The diversity of wilderness visitors ranges from those who take short walks and view scenery and wildlife in an hour to multiple-day backpackers, week-long backcountry hunting trips with pack animals, and mountain climbing expeditions. Growth in the amount of recreation demand and the increasing popularity of many forms of recreation in wilderness are due to U.S. population growth and a general upward trend in participation in many activities, on all types of sites, in the United States1 on public or private lands. Although backcountry and wilderness use is distributed across the full geographic and sociodemographic spectrum, there is an identifiable 8.6% of the U.S. population that has been labeled as “backcountry actives” by one researcher because of their 2.5 times or greater above-average participation in such activities as backpacking, wilderness visits, cross-country skiing, and day hiking.1

Studies at high-use federal agency sites of visitor use of wilderness in the mid-1990s estimated that more than 14 million visitors went to the wilderness per year.2 Public surveys of the general population in recent years estimated that visitation was closer to 40 million per year.2 Most estimates of future growth suggest that wilderness use will continue to increase (2% to 4% per year) and that participation will continue across a wide range of activities.1,2

Recreation enthusiasts spending seven or more days in wilderness or primitive areas per year are a growing market segment that includes participation in strenuous physical activities on a regular basis.1 Improvements in and availability of high-technology gear permit travel in all types of weather conditions and terrain, so that regular use across the entire landscape makes it more difficult to manage use in general, as well as more challenging to conduct search and rescue operations. Risk-taking, exploring, and adventure activities are increasingly prevalent because of media exposure, easier access to sites, more available high-technology gear, more opportunities for initiation into activities, and more training and skill-building opportunities. There is some concern that communication equipment, like satellite cell phones, and navigational equipment, like handheld Global Positioning System (GPS) units, may contribute to the impression that a person could call for help more readily and therefore take greater risks than their skills otherwise would warrant.

One of the ways that people are initiated into wilderness use and gain training in primitive travel and living is through participation in Wilderness Experience Programs (WEPs). The number of WEP organizations and their clientele have grown rapidly in the United States in the past two decades.7 Wilderness land managers recognize WEPs as a significant user group with a focus on programs in wilderness and primitive areas as one of their defining characteristics.6

The most prevalent three types of WEPs are (1) educational programs where the wilderness ecosystem is the focus of the instruction, research, and field trips; (2) personal growth and development, where wilderness is the setting and metaphor for everyday life, with insights achieved from challenging activities and reflection; and (3) therapy and healing, where wilderness is the setting to seek restored normal functioning and a healthy balance through primitive living and traveling.6,7 Although the healing aspects of a natural environment8 and wilderness areas are well documented, the inherent risks of traveling in remote areas must be recognized through risk management assessment and contingency planning,17 especially for human health and safety.

Distribution of Wilderness Visitor Use

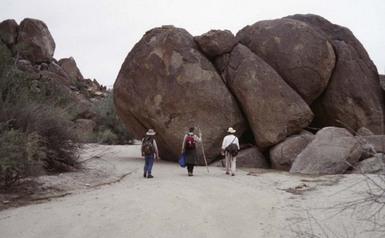

Some of the greatest variations in visitation are due to seasonality and opportunity for use. Each area has a favored season for a given type of activity. Even though most hiking and camping activities occur during late spring through early fall, some areas have other peak use times because of weather and opportunities present. For example, spring fishing and whitewater boating may occur in the same area, whereas fall hunting and backpacking during fall foliage may be followed by cross-country skiing and winter camping. Cooler weather in desert areas may bring visitors in nonsummer months (Figure 112-4). Warmer months in alpine areas may bring large numbers of visitors. Weekend and weekday variations are normal fluctuations due to work week schedules.

Wilderness Management Principles

The guiding principles for managing wilderness areas5 revolve around the idea that wilderness needs to be managed as a pristine extreme in the landscape (>4% of U.S. land area) to maintain the distinctive qualities that define and separate wilderness from other land uses (>95% of U.S. land area). Wilderness is managed from the biologically centered perspective. Environmental integrity and primeval conditions of wilderness are the basis for any human enjoyment, values, and benefits.

Wilderness Preservation as a National and International Movement

The U.S. legislative model has influenced some forms of international wilderness protection,11 although the variation in level and type of protection is complex and based on the cultural and legislative history in each country. The concept of wilderness is universal, but the national legislative approach used in the United States has been widely adopted by other countries, such as Canada, Australia, Finland, Russia, and South Africa.11 There are dozens of international organizations that one can join to help protect wilderness. Some examples include the WILD Foundation (http://www.wild.org), Conservation International (http://www.conservation.org), and IUCN—The World Conservation Union (http://www.iucn.org). Many non-U.S. countries have strong public support for wilderness and related organizations that support wilderness designation and stewardship.

Wilderness protection and management of federal lands in the United States is under the jurisdiction of four federal agencies: the NPS, BLM, FS, and WFS. Each of these agencies has policy and operational information that is important for visitors to understand. This information is available at agency websites, but is easy to obtain through websites such as http://www.wilderness.net that allow access from a geographic map that, in turn, brings the viewer to useful information from the designating legislation to the managing agency and local-level contact offices for that wilderness unit. Obtaining local contact information and some general visitor management information makes wilderness visitation more enjoyable and improves the pretrip planning process, including compliance with local regulations.

Wilderness stewardship organizations in the United States include many that have been involved in wilderness issues for decades. Only a few examples are listed here: The Wilderness Society (http://www.wilderness.org), Sierra Club (http://www.sierraclub.org), American Wilderness Coalition (http://www.americanwilderness.org), Campaign for America’s Wilderness (http://www.leaveitwild.org), Wilderness Watch (http://www.wildernesswatch.org), National Wildlife Federation (http://www.nwf.org), National Audubon Society (http://www.audubon.org), and the Izaak Walton League (http://www.iwla.org).

Wilderness preservation is a national and international movement comprising grass roots and membership organizations interested in protection and stewardship of our dwindling wild areas. Although the concept and values of wilderness are supported by the general population of the United States and many other countries, it is the continued support and work of many people and organizations that stimulate the legislative and administrative branches of our government to continue their efforts to maintain parts of our country wild for present and future generations. The reader is encouraged to become part of that wilderness preservation movement. For a comprehensive resource, the reader is referred to Dawson and Hendee.5

1 Cordell HK. Outdoor recreation for 21st century america: A report to the nation: The National Survey on Recreation and the Environment. State College, PA: Venture Publishing; 2004.

2 Cordell HK. Outdoor recreation in American life: A national assessment of demand and supply trends. Champagne, Illinois: Sagamore Publishing; 1999.

3 Cordell HK, Bergstrom JC, Bowker JM. The multiple values of wilderness. State College, Pennsylvania: Venture Publishing Inc; 2005.

4 Cordell HK, Tarrant MA, Green GT. Is the public viewpint of wilderness shifting? Inter J Wilderness. 2003;9:27.

5 Dawson CP, Hendee JC. Wilderness management: Stewardship and protection of resources and values, ed 4. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing; 2009.

6 Dawson CP, Tangen-Foster J, Friese GT, et al. Defining characteristics of U.S.A. wilderness experience programs. Intern J Wilderness. 1998;4:22.

7 Friese GT, Hendee JC, Kinziger ML. Wilderness experience program industry in the United States: Characteristics and dynamics. J Exper Educ. 1998;21:40.

8 Frumkin H. Beyond toxicity: Human health and the natural environment. Am J Prevent Med. 2001;20:234.

9 Hendee JC, Dawson CP. Wilderness progress after forty years under the U.S. Wilderness Act. Inter J Wilderness. 2004;10:4.

10 Kormos CF. A handbook on international wilderness law and policy. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing; 2008.

11 Martin VG, Watson A. International wilderness. In: Dawson CP, Hendee JC, editors. Wilderness management: Stewardship and protection of resources and values. ed 4. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing; 2009:50-88.

12 Nash RF. Wilderness and the American mind, ed 4. New Haven, Connecticut: Yale University Press; 2001.

13 Propst BM, Dawson CP. State-designated wilderness in the United States: A national review. Inter J Wilderness. 2008;14:19.

14 Sanderson EW, Jaiteh M, Levy MA, et al. The Human footprint and the last of the wild. Bioscience. 2002;52:891.

15 Scott DW. The enduring wilderness: Protecting our national heritage through the Wilderness Act. Golden, Colorado: Fulcrum Publishing; 2004.

16 Scott DW. The Wilderness Act at forty; looking back, looking ahead. Inter J Wilderness. 2004;10:8.

17 Tangen-Foster J, Dawson CP. Risk management programs in wilderness experience programs. Inter J Wilderness. 1999;5:29.

18 U.S. Public Law 88-577, The Wilderness Act of September 3, 1964, 78 Stat. 890.