Chapter 30 Wilderness Dentistry

For online-only figures, please go to www.expertconsult.com ![]()

History and Examination

History taking for dental emergencies proceeds as with any other condition. In emergency situations, the chief complaint and history of the present illness deserve greater emphasis than family, personal, and social history and review of systems. However, the presence of complicating medical factors or chronic illness may prove very important in choosing the proper treatment. Many commonly used medications have bearing on dental diagnosis and treatment. Emphasis on the need for subacute bacterial endocarditis (SBE) prophylaxis, bleeding disorders, immunosuppression, allergies, and current medications is a good start. The American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons2 recently changed their recommendations to state that persons with total joint replacements should receive antibiotic prophylaxis before invasive procedures. The American Heart Association recommendations for SBE prophylaxis have also changed recently and are listed in Boxes 30-1 to 30-3. Note that premedication is no longer recommended for patients with most types of heart murmurs.50

BOX 30-1

Antibiotic Prophylaxis for Dental Procedures for Patients With Cardiac Conditions

Data from Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al: Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association—A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group, J Am Dent Assoc 139:3S, 2008.

BOX 30-2

Data from Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al: Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association—A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group, J Am Dent Assoc 139:3S, 2008.

Dental Procedures for Which Prophylaxis Is Reasonable in Patients With the Cardiac Conditions Listed in Box 30-1

BOX 30-3

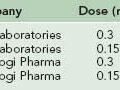

Antibiotic Prophylactic Regimens for Dental Procedures (Single Dose 30 to 60 Minutes Before Procedure)

Data from Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al: Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association—A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group, J Am Dent Assoc 139:3S, 2008.

Maxillofacial Pain

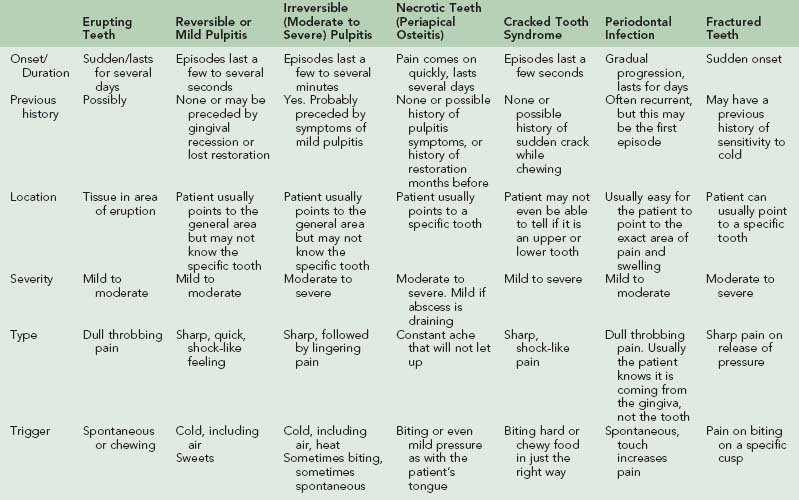

The causes of maxillofacial pain are myriad, and the diagnosis of head and neck syndromes can be exceedingly difficult.32,33 The most common painful conditions are covered below. If the victim’s symptoms do not seem consistent with a dental origin, other causes should be suspected. Examples of disorders that are sometimes confused with dental pain are myofascial pain, maxillary sinusitis, temporal arteritis, and trigeminal neuralgia. Box 30-4 lists others. Table 30-1 shows the characteristics of specific types of tooth-related pain that can assist the examiner in sorting out a diagnosis.

Pulpitis

The common toothache is caused by inflammation of the dental pulp. It may be difficult for the victim to identify the offending tooth due to convergence of neurons in the trigeminal spinal tract nucleus.9,26 The painful tooth is rarely sensitive to percussion or palpation. An obvious cause, such as a large carious lesion, is sometimes found on examination of the mouth, but often all of the teeth appear intact. If inflammation is mild, the condition is characterized by pain that is elicited only by cold or sweets and disappears within seconds when the stimulus is removed. Moderate pulpitis is characterized by sensitivity to hot as well as cold, greater discomfort, and an increasing interval between the removal of the stimulus and resolution of the pain. In its most severe form, pulpitis causes intense, continuous, and debilitating pain.6,9,33 Emergency treatment recommendations are given in the following sections.

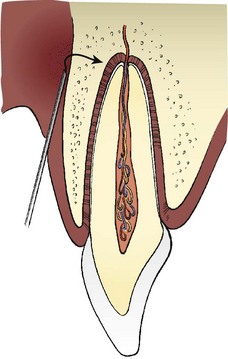

Severe Pulpitis (Intense, Continuous Pain)

The preferred approach is pain relief using a local anesthetic, followed by evacuation of the victim.35,47 A nerve block with bupivacaine (Marcaine) 2% with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine can provide up to 8 hours of excellent pain relief without central nervous system depression (see Local Anesthesia, later). Nonsteroidal antiinflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) will probably give little relief. Large doses of narcotics should not be used because they are likely to compromise the victim’s ability to participate in evacuation. Sometimes application of cold (continuously sipping cold water) provides relief to the hyperemic pulp. In an extraordinary circumstance, an experienced rescuer could locate the offending tooth, expose the pulp, remove the inflamed pulpal tissue with a barbed broach, and cover the opening with a temporary filling material. Extraction is also an option in a case of severe pulpitis but is usually contraindicated for a number of reasons (see Exodontia, later).

Periapical Osteitis

Inflammation of the supporting structures at the root of a tooth is characterized by constant, often throbbing, pain. Unlike pulpitis, the affected tooth is easily located. The victim can usually point to the exact source of the pain, or the examiner may gently tap individual teeth, observing for tenderness. The area over the apex of the tooth is usually tender to palpation, but there is no frank swelling. Although trauma to a tooth can result in periapical inflammation, the most common cause is egress of bacteria and breakdown products from the necrotic pulp. Minor swelling around the apex extrudes the tooth slightly, causing increased forces on the tooth during occlusion, and thus intensifies the pain. Emergency treatment includes an analgesic (ibuprofen 600 mg PO every 6 hours as needed for pain) or a local anesthetic and a soft diet. Ideally, the contacting areas of the opposing tooth are reduced to relieve occlusal forces.6,9 Because this usually is impractical in the field, the victim can be given a strip of webbing or something similar to place between the teeth on the nonpainful side. This will keep the offending tooth out of occlusion and reduce the pain.

Cracked Tooth Syndrome

The victim complains of momentary, sharp pain when chewing certain foods or on releasing the bite. Often the victim reports that the tooth feels “weak” or that “it only hurts when I bite on something hard just the right way.” These symptoms occur when forces of the proper magnitude and direction open the incomplete fracture in the tooth.37 The pain can vary with a cracked tooth depending on how deep the crack is and how close it comes to the pulp. Significantly, there is no pain on chewing soft foods. Often the victim has large restorations or a habit of chewing ice or clenching and grinding.22 This condition usually progresses slowly. Reducing the occlusion on the cracked tooth will relieve some pain but again is often impractical in the field. The victim should be advised to avoid chewing on the affected side and to seek definitive dental treatment as soon as possible.

Odontogenic Referred Pain

Pain originating in the pulp of the tooth can sometimes be referred to distant sites. Common referral patterns are the following: maxillary incisors to the forehead, maxillary canine to the infraorbital area, maxillary molars to the temple or ear area, mandibular anterior teeth to the mental foramen area, mandibular premolars to the posterior jaw, and mandibular molars to the angle of the jaw, the ear, or the neck. Sometimes the victim swears the pain is coming from a tooth several teeth in front or behind the source of pain. Pulpitis pain can be referred from an upper tooth to a lower tooth, or vice versa, but never crosses the midline. Many cases have been presented in the dental literature detailing how experienced practitioners have treated the wrong tooth or performed multiple dental treatments when the source of pain was not a tooth.26,30 If in doubt about the diagnosis, ensure that you do no harm.

Maxillary Sinusitis

Treatment of maxillary sinusitis includes an analgesic (ibuprofen 600 mg PO every 6 hours as needed for pain), inhalation of steam, oxymetazoline (Afrin) 0.05% 1 spray in each nostril twice a day to shrink the nasal membranes and improve sinus drainage, and an antibiotic. Appropriate choices include amoxicillin 875 mg with clavulanic acid 125 mg (Augmentin) PO twice a day for 10 days or trimethoprim 160 mg with sulfamethoxazole 800 mg (Septra DS) PO twice a day for 10 days. Azithromycin (Zithromax) 500 mg PO the first day and then 250 mg PO for 4 days is a convenient alternative.1,19

Temporomandibular Disorder

Temporomandibular disorder (TMD) is a cluster of conditions, multifactorial in origin, and with overlapping symptoms that often respond to a variety of therapies, including placebos.31 If the victim answers “yes” to any of the following questions, he or she may suffer from TMD: Does it hurt to open the mouth widely or yawn? Do you have earaches or pain in front of your ear? Is your pain worse in the morning? Have you had trauma to your face or jaw? Do you have temporal pain or headaches? Has your jaw ever gotten stuck open or closed? Does your jaw pop or click on opening or closing?

Included under the term TMD are two groups of sufferers: those with primary masticatory muscle involvement (myofascial pain and dysfunction [MPD]) and those with internal derangements of the temporomandibular joint (TMJ). Patients also may present with a combination of both types. Internal derangements, traumatic injuries, and dislocation of the joint are covered in Chapter 31.

Myofascial Pain and Dysfunction

Muscle hyperactivity is an important etiologic factor in MPD. In some persons this may result from parafunction (gum chewing, clenching or grinding the teeth). Occlusal interferences can also cause muscle hyperactivity. This occurs when a lower tooth contacts an upper tooth prematurely during mouth closure and a reflex causes jaw muscle contraction that shifts the mandible in such a way as to avoid the premature contact. For this reason this condition is often referred to as an “occluso-muscle disorder.” Psychological stress is also an important factor in causing excessive muscle tension.25

Symptoms of MPD include pain in the muscles of mastication that is usually unilateral and increased with chewing, headache, earache, limitation of jaw movement, and a change in the bite. Pain originating in the muscles of mastication is often referred to the teeth, so the chief complaint may be a toothache.26,40 The victim may have a history of acute onset, or a long saga of exacerbation, remission, and various treatments.

The examiner may find objective signs, such as tenderness of the jaw muscles to palpation, muscle spasm or “knots,” and abnormal jaw movements, such as inability to open the mouth widely, or deviation of the chin to one side on opening. Tenderness to palpation of the TMJ or joint noise suggest the victim has an internal derangement of the joint.25

Emergency treatment consists of resting the muscles (soft diet and control of tooth clenching and grinding habits) and the application of moist heat. Holding a soft material such as a folded gauze between the front teeth or use of an athletic mouth guard often gives immediate relief because it keeps the teeth from touching and allows the muscles to relax. An analgesic should be given on a scheduled basis (ibuprofen 600 mg PO every 6 hours), rather than as needed, to break the cycle of muscle pain and spasm. A muscle relaxant, such as cyclobenzaprine hydrochloride (Flexeril) 10 mg PO 3 times a day, or sedatives, such as diazepam (Valium) 2 to 10 mg PO 3 times a day, may be helpful if the primary treatment is ineffective. Muscle relaxants and sedatives, especially in higher doses, can cause significant central nervous system depression, so they should be used in the lowest effective dosage and only if more conservative therapy has failed.10,31,42

Miscellaneous Lesions

Aphthous Ulcers

It is thought that aphthous ulcers may represent a local immune response with various triggers such as stress; trauma; immunosuppression; nutritional deficiencies of vitamin B12, folic acid, or iron; acidic foods; and food allergies; to name a few. The lesions are round or ovoid in shape with a yellowish center and a red border and usually occur on nonkeratinized, movable mucosa (Figure 30–1). They can be quite painful. The victim usually gives a history of similar ulcerations. There are three types of aphthous ulcers. Minor aphthae are less than 0.6 cm (0.2 inch) in size and usually last 10 to 14 days. Major aphthae are larger than 0.6 cm (0.2 inch) and may last weeks or months. Herpetiform aphthae are clusters of small, shallow ulcers that resemble intraoral herpes.

Many treatments have been proposed, but none has been found predictably effective. The best approach appears to be application of a topical corticosteroid to reduce pain and hasten healing by 3 to 4 days. Mix fluocinonide (Lidex) 0.05% ointment with Orabase and place the mixture gently over each ulcer 6 to 8 times per day, especially after meals and before bedtime. Do not mix the medications until you are ready to apply them, and do not rub the mixture into the lesions. Other options include premixed preparations, such as Kenalog in Orabase, applied to the ulcer 6 to 8 times per day, which is more convenient but delivers only about 10% of the antiinflammatory effect, or dexamethasone (Decadron) elixir (0.5 mg/5 mL, rinse with 5 mL for 2 minutes and expectorate 4 times a day). Finally, a systemic corticosteroid (prednisone, 40 mg PO once daily for 3 days, then taper) may be used for a very severe case. If these preparations are not available, tincture of benzoin or a topical anesthetic (viscous lidocaine 2%) can be applied to the dried surface of the ulcer before meals and at bedtime to control the pain.15,45

Bisphosphonate-Related Osteonecrosis of the Jaws

Oral bisphosphonates such as alendronate (Fosamax) are widely used to treat osteoporosis, and intravenous bisphosphonates, such as zoledronic acid (Zometa) are used to manage skeletal involvement in various cancers. A side effect of these medications can be delayed healing of exposed bone in the maxillofacial region. Altered bone metabolism persists long after the medications have been discontinued. Bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws (BRONJ) may occur after bone is exposed by acute trauma, by chronic trauma such as from an ill-fitting dental prosthesis, from dental surgery, or after tooth extraction. The incidence after tooth extraction in patients that have taken oral bisphosphonates is less than 1%. The risk for BRONJ in patients that have received intravenous therapy is estimated between 0.8% and 12%.3

The diagnosis of BRONJ is made when exposed, necrotic bone persists for at least 8 weeks in a patient currently or previously treated with a bisphosphonate who has no history of radiation treatment to the jaws. Small lesions may be asymptomatic (Figure 30-2, online), whereas some exposed areas become infected, as evidenced by pain, erythema of the surrounding soft tissue, and possible purulent drainage. Prevention of BRONJ focuses on avoiding bone exposure in patients at risk. Emergency management consists of eliminating pain, controlling infection, and limiting the progression of bone necrosis. Asymptomatic lesions are treated with an antibacterial mouth rinse such as chlorhexidine. BRONJ that is painful and infected is treated with an antibacterial mouth rinse as well as an antibiotic, such as penicillin V potassium 500 mg PO 4 times a day, cephalexin (Keflex) 500 mg PO 4 times a day, or clindamycin 150 mg PO 4 times a day, and pain control. Evacuation for surgical care is indicated in cases of BRONJ complicated by any one of the following: pathologic fracture, extraoral fistula, or necrosis extending to the inferior border of the mandible.3,27,38

Mucocele

Mucocele, or mucous retention phenomenon, occurs when the duct of a minor salivary gland is blocked or traumatized, resulting in accumulation of saliva beneath the mucosa. It most commonly occurs in the lower lip. A mucocele in the floor of the mouth is called a ranula. Most mucoceles are a few millimeters in diameter, lie just under the surface, and have a translucent or bluish tint. They often form, spontaneously drain, then reform again and again. Most will eventually disappear without surgical intervention. No emergency treatment is necessary (Figure 30-3).

Maxillofacial Infections

Viral Infections

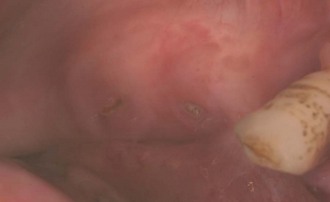

Herpes labialis (cold sore, fever blister) is the most common oral viral infection. It is characterized by yellow, fluid-filled vesicles that rupture to leave ragged ulcers on the lips (Figures 30-4 and 30-5). Other locations for recurrent herpetic outbreaks include the palate, tongue, and buccal mucosa. The victim can be given valacyclovir (Valtrex) 2 g PO twice daily for 1 day, with doses taken about 12 hours apart.43 It is important to begin treatment as soon as the victim becomes aware of a prodromal “tingle” or paresthesia. There is some evidence that the same regimen of valacyclovir can prevent outbreaks from occurring.8,29 However, more conservative methods, such as the use of sun-blocking agents on the lips, are preferred.44

Yeast Infections

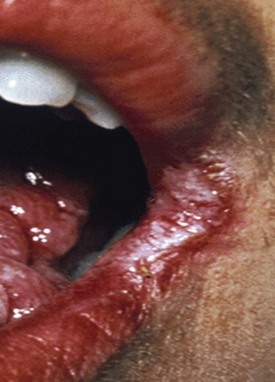

Oral yeast infections occur most commonly in persons who are debilitated, immunocompromised, suffer from xerostomia, or are taking an antibiotic or corticosteroid. Classic oral candidiasis (thrush) is characterized by white patches on the mucosa that can be rubbed off, leaving a red and raw surface (Figure 30-6). Candidiasis can also manifest as erythematous mucosa, without any white patches, or as chronic angular cheilitis (Figures 30-7 and 30-8; Figure 30-8, online). Candidiasis is treated with an antimycotic mouth rinse (nystatin oral suspension 100,000 U/mL, rinse with 5 mL for 2 minutes and swallow, 4 times a day for 10 days) or lozenges (clotrimazole [Mycelex] troche, 1 troche 4 times a day, leave in mouth 5 minutes, and expectorate remains). In the field, nystatin preparations meant for vaginal treatment (Nystatin vaginal suppository used as an oral lozenge 3 times a day for 10 days) can be used.

Bacterial Infections

The behavior of an organism, such as the production of collagenase or hyaluronidase, determines the clinical presentation. Thus an infection may manifest as diffuse cellulitis or localize as an abscess. Oral infections usually spread slowly, but rapid spread to a deep facial space can occur. Regional lymphadenopathy is common, whereas severe systemic symptoms are rare. Although bone is often involved, osteomyelitis is uncommon.39

Acute Apical Abscess/Cellulitis

The victim presents with pain and swelling, often fluctuant and usually in the buccal vestibule (Figure 30-9). There is often a history of prior toothache, but at this stage tooth pain is often absent. The offending tooth can be localized by percussion, site of the swelling, condition of the teeth, and by radiographs if available. The affected tooth does not respond at all to hot or cold. The victim may be dehydrated because of decreased fluid intake.

Primary treatment for an apical abscess is drainage.28,41 This can be accomplished with incision, extraction, or endodontic therapy. The treatment chosen depends on the equipment and personnel available, advisability of retaining the offending tooth, and ultimately on clinical judgment. An antibiotic is necessary only if complicating factors exist11,28,41,46 (Box 30-5). Penicillin V potassium 500 mg PO 4 times a day is the most commonly used antibiotic in dental practice, but a cephalosporin, such as cephalexin (Keflex) 500 mg PO 4 times a day, typically carried on wilderness expeditions, is acceptable. Clindamycin 150 mg PO 4 times a day is a good alternative.23,41,46 Combination antibiotic therapy is not indicated except for life-threatening sepsis or when organisms particularly sensitive to combination therapy have been identified. There is some evidence that hesitation to obtain drainage combined with overreliance on chemotherapy can lead to serious exacerbation of dental infections.11

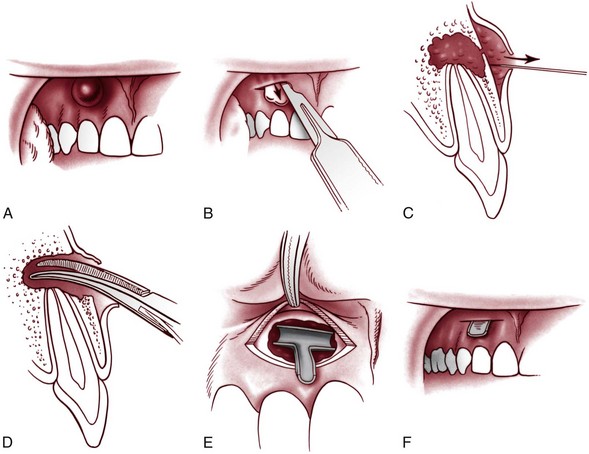

Incision and Drainage

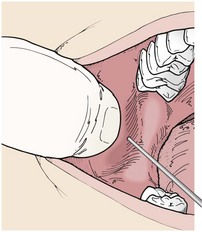

Incision and drainage (I&D) is often the treatment of choice in an emergency situation. An I&D procedure can be performed by a nondentist using commonly available supplies. It is indicated for fluctuant swelling due to an apical abscess and may also be effective for nonfluctuant swelling associated with infection. Infiltration of a local anesthetic helps to reduce the pain of incision. If unavailable, adequate anesthesia can often be obtained by applying cold to the area to be incised, using ice, snow, or frigid water. An incision is made down to the bone in one swift motion, and a knife handle or the beak of a hemostat is used to spread the incision. A T-shaped drain may be improvised from a piece of latex glove and retained without sutures (Figure 30-10). Hydration, a soft diet, an analgesic (ibuprofen 600 mg PO every 6 hours as needed for pain), and warm saline rinses are helpful postoperative measures.

Deep Fascial Space Infections

An acute apical infection occasionally spreads beyond the local region. The rescuer should be suspicious of any dental infection that causes swelling or tenderness in the floor of the mouth, swelling of the tongue, dysphagia, breathing difficulty, or trismus, or that fails to respond to appropriate therapy. The most commonly involved fascial spaces are the canine, buccal, masticator, and submandibular spaces.12

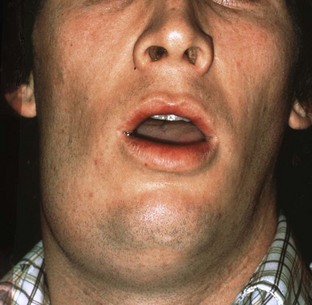

Buccal space infection is characterized by rounded swelling of the cheek (Figure 30-11). The offending teeth are the maxillary and mandibular molars. Drainage is obtained extraorally through an incision below the lower border of the mandible, so that the scar will eventually be hidden or minimal.

The mylohyoid muscle divides the floor of the mouth into the sublingual and submandibular spaces. These communicate posteriorly and with their counterparts across the midline. An infection originating in a mandibular tooth can involve these spaces. If only the sublingual space is infected, an intraoral approach is used for drainage, avoiding damage to Wharton’s duct. If the submandibular space is involved, an extraoral approach is used. All incisions in the facial area are made parallel to branches of the facial nerve.12,24

Fascial space infections are potentially life threatening. The likelihood of widespread sepsis increases, cavernous sinus venous thrombosis and mediastinitis are possible, and the airway may become compromised.13,17 The most feared infection is Ludwig’s angina, a bilateral submandibular space infection that elevates the tongue, obstructs breathing, and is associated with a high mortality rate (Figure 30-12). A mild dental infection can progress to a life-threatening emergency in as little as 48 hours.17

Chronic Apical Abscess

The hallmark of chronic apical infection is a draining fistula or “gum boil” (Figure 30-13, online). Because the bacteria have a route to escape, they do not cause pressure or pain, although the tooth may be mildly sensitive when eating. Such an abscess is not an emergency except in the unlikely event of an acute flare-up. Antibiotics are not indicated.

Acute Necrotizing Ulcerative Gingivitis

Acute necrotizing ulcerative gingivitis, also known as trench mouth, is characterized by ulceration and blunting of the interdental papillae. The gingiva between the teeth appears punched out and is covered by a gray/white pseudomembrane, whereas the surrounding gingival tissue is very red. The victim’s primary complaint is pain, but he or she may also report gingival bleeding, metallic taste, and foul odor. This infection is caused by fusiform bacteria and spirochetes. It usually occurs in young adults with poor oral hygiene, stress, and suboptimal nutrition (conditions that may be present during difficult wilderness expeditions). The most important treatment is gentle debridement of plaque, calculus, and food from around the teeth. Resolution may require several sessions of careful cleaning 1 to 2 days apart. Each session of debridement results in some healing, which allows more aggressive treatment the next time. The victim is also given an antibiotic (metronidazole [Flagyl] 500 mg PO 4 times a day) and analgesics (ibuprofen 600 mg PO every 6 hours as needed for pain) and instructed to keep the area clean with good brushing, flossing, and rinsing (warm saline or diluted hydrogen peroxide, if available).6

Exodontia

A dental extraction is considered definitive treatment and should be attempted in the field only under extraordinary circumstances (Box 30-6). Extraction requires training, specialized instruments, and profound anesthesia, which may be difficult to obtain. As discussed above in the section on facial pain, symptoms that seem to be coming from a maxillary molar may actually originate in a lower molar or from a muscular trigger point. Never extract a tooth without a definitive diagnosis. Premedication with a sedative or narcotic may be necessary, as may dental radiographs. Intraoperative and postoperative complications are common. Providers of emergency care should focus on treating pain and infection with local anesthetics, analgesics (ibuprofen 600 mg PO every 6 hours as needed for pain, or hydrocodone 7.5 mg and acetaminophen 750 mg [Vicodin ES] PO every 4 to 6 hours as needed for pain), I&D, and antibiotics (see Acute Apical Abscess/Cellulitis, earlier) as appropriate for each case.6,35,41 Extraction or other definitive care can then be rendered after evacuation; the tooth can often be saved.

BOX 30-6 Factors to Consider Before Extraction of Teeth

Other factors to consider before exodontia are degree of mouth opening possible, relationship of the root to the maxillary sinus, condition of the clinical crown, alignment of the tooth in the dental arch, and history of previous endodontic treatment (after root canal treatment, a tooth is usually very brittle).21 Along with the considerations for extracting the tooth, weigh the possible complications arising from extraction, such as fractured roots, fractured alveolus, fractured mandible or tuberosity, damage to adjacent teeth and restorations, soft tissue injury, loss of root tip in sinus, prolonged bleeding, and infection.

Review the victim’s medical history. There are dental implications for many frequently prescribed medications.7 Chapter 34 discusses chronic diseases and wilderness activities. Do not assume that the victim is free of bleeding disorders, severe cardiovascular disease, and the like. A discussion of dental surgery for the patient on anticoagulant therapy and maximum international normalized ratio (INR) values for various procedures is beyond the scope of this chapter. Suffice it to say, you do not want to exceed those values in a wilderness setting! Persons with certain cardiac conditions or recent prosthetic implants should be premedicated with an antibiotic2,50 (see Boxes 30-1 to 30-3). Consider the emotional state of the victim, and decide if sedation is prudent.

Teeth are inflexible and brittle. Heavy forces, especially if applied quickly (high acceleration), break teeth. Bone has more flexibility, the degree of which depends on the individual patient. Judiciously applied, moderate forces slowly expand the bone. The tooth will eventually be delivered in the same direction as if it continued to erupt. However, do not attempt to “pull” the tooth in that direction initially. The direction of force needed to loosen a tooth depends on the anatomy of the root. A straight, conical root can be loosened by twisting forces. This technique often works well on the upper front teeth. Sometimes a tooth can be removed by alternating 30 seconds of steady pressure toward the cheek with 30 seconds of steady pressure in the opposite direction, until the root gradually loosens.52

A variety of instruments can be used to apply force to the tooth. Elevators are firmly wedged between tooth and bone in the interproximal area. Avoid putting pressure on the adjacent tooth. Forceps should be applied as far apically as possible. Spend plenty of time working the forceps well under the gingiva. Lower molars are often removed with “cowhorn” forceps, which, in addition to applying the usual forces, are designed to apply force to the tooth in a coronal direction simply by squeezing the handles. However, an experienced exodontist using careful technique and a single forceps (the No. 151 universal extraction forceps) (Figure 30-14) will have success extracting almost any nonimpacted tooth, whereas a reckless operator using dozens of specialized instruments will have difficulty.21,52

Dental Trauma

Wilderness recreation creates many opportunities for traumatic injury. One recent survey of 9543 consecutive trauma patients registered with an oral and maxillofacial surgery service found that 31% were sports related. Of those, 44% could be considered “backcountry” trauma, mostly resulting from skiing and snowboarding. The study was done in Innsbruck, Austria.49

It is essential to quickly evaluate the general condition of an injured victim (see Chapter 21). The primary survey identifies and corrects any inadequacy in respiration or circulation. The mouth and pharynx should be examined for foreign bodies such as blood clots, tooth or bone fragments, or dentures. If the airway is still obstructed, it may be necessary to perform a chin lift or jaw thrust or insert an oropharyngeal airway to hold the tongue forward (see Chapter 20). Care should be taken not to hyperextend the neck because of the possibility of a cervical spine fracture. If there is no indication of a neck fracture, sometimes merely placing the victim on his or her side rather than in a supine position facilitates respiratory exchange. If all these measures fail, endotracheal intubation or performance of a cricothyrotomy or, less commonly, a tracheotomy may be necessary.5 Once a victim’s airway is secured and he or she is hemodynamically stable, perform a secondary survey.

Question the victim about the time and nature of the accident, symptoms, loss of consciousness, nausea, vomiting, visual disturbances, and headache. A baseline mental status examination and cranial nerve assessment may be warranted. Clean the face, mouth, head, and neck of blood and debris. This unmasks soft tissue injuries and facilitates diagnosis. Gently reflect the lips with teeth closed to examine soft tissues and occlusion. Examine any lacerations carefully to determine if they penetrate through the lip or contain foreign material. Examine all of the teeth for fractures. A blow to the chin or whiplash injury may produce fractures of the posterior teeth as the mandible is forcibly closed. Examine fractured teeth carefully for pulp exposure. This will require drying the tooth with gauze. Tap each tooth with an instrument handle. Tenderness denotes injury to the periodontal ligament, whereas a high-pitched, metallic sound indicates ankylosis as occurs in lateral luxation or intrusion. Test each tooth for abnormal mobility. Electrical pulp vitality testing, dental radiographs, and soft tissue radiographs should be obtained if available.4,16

See Chapter 31 for injuries to the face, head, and jaws.

A classification of traumatic injuries to the teeth and supporting structures is given in Box 30-7. Note that these injuries often occur in combination, with one tooth exhibiting two or more injuries, or several teeth exhibiting various sequelae of trauma. Each injury requires definitive treatment, but proper emergency care improves the prognosis and makes the victim more comfortable. Treatment of most injuries requires, or is at least facilitated by, infiltration of a local anesthetic.

BOX 30-7

Classification of Dental Trauma

From Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM: Textbook and color atlas of traumatic injuries to the teeth, ed 3, St Louis, 1994, Mosby.

Specific Dental Injuries

Uncomplicated Crown–Root Fracture

Diagnosis and treatment of this condition are identical to the uncomplicated crown fracture, except that the fracture is nearly vertical, leaving a small, chisel-shaped fragment attached only by the palatal gingiva (Figure 30-15). Removal of this mobile fragment makes the victim much more comfortable.

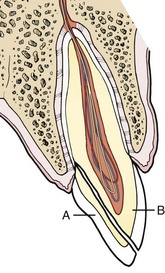

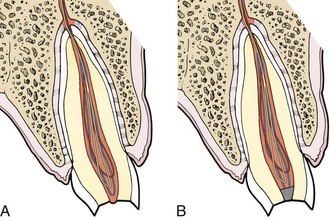

Complicated Crown Fracture

In this injury, the pulp has been exposed. A small exposure that has not been grossly contaminated is capped with calcium hydroxide (Dycal) or IRM. If the exposure is larger than 1 mm or if the pulp tissue has been exposed for more than 24 hours, amputate approximately 2 mm of tissue with a sharp, sterile instrument. If bleeding continues for more than a few minutes, use a cotton pellet soaked in local anesthetic solution, hydrogen peroxide, or Dycal to obtain hemostasis. Fill the top of the canal with Dycal or IRM, and protect the tooth as for a crown fracture (Figure 30-16).

Complicated Crown–Root Fracture

The tooth has been fractured obliquely, resulting in a mobile fragment attached to the palatal gingiva as well as a pulp exposure. First, remove the mobile fragment as in a crown–root fracture, then treat the pulp exposure as in a complicated crown fracture.4 It is possible to glue tooth fragments together with 2-octyl cyanoacrylate (Dermabond) for a day or two.20

Root Fracture

A root fracture may be difficult to diagnose without radiographs. There is slight to severe malposition of the crown, but this could be caused by extrusion of the entire tooth or a root fracture with luxation of the coronal portion. Reposition the tooth as precisely as possible, and splint rigidly (see Splinting, later). Hard tissue union of the fragments usually occurs within 3 months. If the coronal portion of the tooth proves impossible to stabilize and definitive treatment is days away, remove the mobile fragment, but do not attempt to extract the apical fragment.4,16

Intrusion

A tooth that has been driven into the bone by a vertical force demonstrates little mobility and a high-pitched, metallic tone on percussion. Emergency treatment is palliative only. Endodontic treatment (to prevent inflammatory root resorption) and orthodontic extrusion should begin within 2 weeks of injury. Intrusion is associated with a poor long-term prognosis.4

Lateral Luxation

In this injury, the tooth is often displaced by a horizontal blow, yet it is not mobile because the apex is locked into its new position in the alveolar bone. A high, metallic tone on percussion is another clue that this has occurred. This injury and its treatment are painful. Figure 30-17 shows how two fingers are used to reduce the tooth. One finger guides the apex down and back, while the other repositions the crown. This requires judicious, but sometimes quite firm, application of force. The tooth may snap back into position and be quite stable. Check the tooth the next day. Breakdown of marginal bone and inflammation may cause the tooth to become mobile. Splinting is necessary if mobility is present, whether this occurs immediately after reduction or is detected later.16

Exarticulation

When a tooth is totally avulsed from bone, the prognosis after replantation depends on the health of the periodontal ligament cells, some of which are still attached to the root surface and some of which line the socket wall.14,36 To preserve the vitality of these cells, certain guidelines should be observed. Keep the time before replantation to a minimum. Immediate replacement is ideal (Figure 30-18). If the tooth must be stored, keep it moist. Less than 20 minutes in air is associated with a good prognosis and longer than 1 hour with a poor prognosis.4,14 If possible, the tooth should be stored in a Save-A-Tooth, which uses a soft mesh to suspend the tooth in Hanks’ balanced salt solution. Alternative transport mediums are whole milk, saline, the victim’s saliva, sports drinks, and water, in that order of preference. The concept is to preserve the health of the periodontal ligament cells in the most isotonic, pH-balanced solution at hand. If no container is available, use a plastic bag, plastic wrap, or saturated cloth to keep the tooth from drying. Handle the tooth by the crown only. Never scrub, curette, or use a disinfectant on the root surface; gently rinse with saline to remove debris. When removing clotted blood from the socket, use gentle irrigation and suction, and avoid scraping the socket walls. Examine the socket for fracture of the alveolar wall. If present, reduce the fractured bone with a blunt instrument. Ease the tooth back into place with slow, steady pressure. After replantation, splint the tooth nonrigidly for 1 week. Suture any gingival lacerations after splinting. Administer an antibiotic for 5 days, and give appropriate antitetanus prophylaxis. Endodontic therapy should be instituted within 2 weeks.4,36

The preferred approach to tooth avulsion or severe luxation is immediate reduction in the field, followed by evacuation for definitive treatment. The next most desirable option is to store the tooth properly and transport victim and tooth for replantation within a few hours of injury. If the extraoral dry time exceeds 60 minutes, the periodontal ligament cells are presumed necrotic and should be removed by curettage. The root is then treated before replantation. Sodium fluoride 2.4% with a pH of 5.5 has been shown to improve prognosis, as have enamel matrix proteins (Emdogain).48

If field conditions prevent all of the aforementioned treatments, a delayed replantation procedure is indicated. Store the tooth dry. Three weeks after the injury, the necrotic pulp tissue is removed and the tooth is disinfected, fluoridated, and surgically replanted. The aim of delayed replantation is to produce ankylosis between tooth and bone.4

Soft Tissue Injuries

Wounds of the oral mucosa and face should be treated after repair of the dental injuries and jaw fractures. Time is more critical when treating intraoral, hard tissue injuries. Also, lacerations are likely to be reopened if closed before intraoral manipulations. See Chapter 31 for diagnosis and treatment of facial soft tissue injuries and Chapter 22 for wound care.

Splinting

When the goal of splinting is to establish a normal, fibrous union between the tooth and the bone, a short-term, nonrigid technique is used. When hard tissue union is desired (e.g., root fracture or alveolar segment fracture), longer-term rigid splinting is used.4 Ideally, a single avulsed or loosened tooth is usually bonded to the adjacent tooth or teeth with the acid etch and composite technique.4,16 For fractures of the jaws or alveolar segments, arch bars and wire splints are often used. The rescuer lacking adequate materials must use ingenuity and improvisation to splint teeth. During a very short evacuation, the victim could hold the tooth in approximate position by closing (biting gently) on a gauze pad. Softened wax can be adapted to a loosened tooth and the teeth on either side to lend support. If the victim has an athletic mouth guard with him or her, this can also be used. Figure 30-19 shows how a suture can be used to hold a tooth in place for a period of a few days. For a sturdier splint, a crude arch bar can be cut from a SAM Splint or made from a paper clip and dead-soft wire obtained from copper wiring or twist ties.

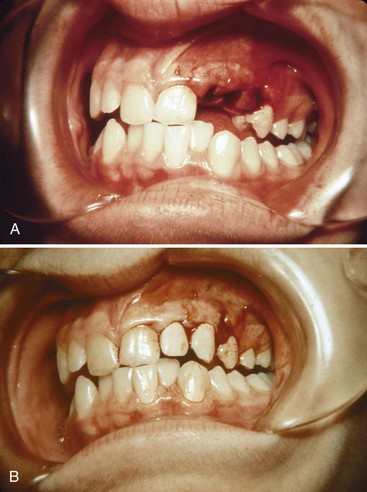

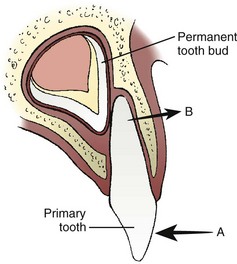

Injuries to Primary Teeth

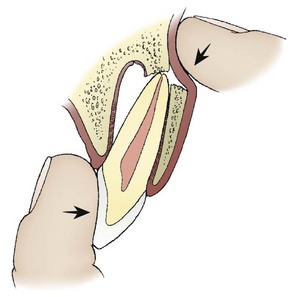

Injuries to the deciduous teeth offer unique challenges, not the least of which is behavioral management of a young child. Splinting is very difficult because of the small amount of tooth structure available. In general, heroic efforts should not be made to save primary teeth.4,16 Exarticulated deciduous teeth should not be replanted. Severely extruded teeth, infected teeth, or those intruded into the developing permanent tooth should be extracted. Because the permanent tooth follicle lies to the lingual side of the primary tooth root, the typical frontal impact displaces the crown toward the palate, but levers the root apex away from the permanent tooth (Figure 30-20). Most minor subluxations and luxations require only symptomatic treatment. As long as the displaced tooth does not interfere with occlusion, reduction is contraindicated. Spontaneous repositioning often occurs over a period of weeks. Fragments of primary roots need not be extracted because normal resorption will still occur.

Local Anesthesia

Local anesthesia is a prerequisite to many emergency dental, oral, and maxillofacial procedures. Anesthesia of any upper tooth and the associated buccal soft tissues can be obtained by infiltration. Approximately 2 mL of a local anesthetic solution is placed as close to the apex of the tooth as possible, just above the periosteum. By holding the syringe parallel to the long axis of the tooth, the needle tip is guided in the proper direction (Figure 30-21). Articaine (Septocaine) 4% with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine has become the most widely used local anesthetic in dentistry.51 Two percent lidocaine with 1 : 100,000 epinephrine is also commonly used, and bupivacaine (Marcaine) 2% with 1 : 200,000 epinephrine is useful for long-term pain relief. Other available local anesthetics can be substituted.

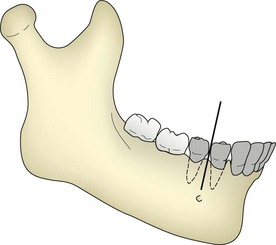

The mental nerve block is a simple method for obtaining anesthesia of the teeth and buccal mucosa from the second premolar forward. Proceed as for the infiltration, except that the target area is the mental foramen, located between apices of the lower first and second premolars (Figure 30-22). After depositing the solution, gently massage the area for about 30 seconds.

FIGURE 30-22 Technique for blocking the inferior alveolar nerve near the mental foramen. The shaded teeth will be anesthetized.

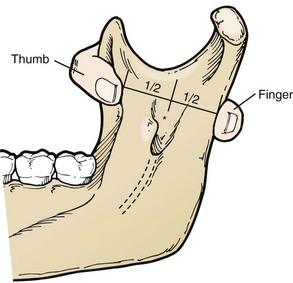

The inferior alveolar nerve block is more difficult to learn but produces anesthesia of all the lower teeth up to the midline, as well as the buccal soft tissues forward of the mental foramen. The lingual nerve is also blocked by this injection, producing numbness of the anterior two-thirds of the tongue and lingual gingiva. Figure 30-23 shows how the deepest concavity on the anterior border of the mandibular ramus is palpated by the thumb while the deepest concavity on the posterior border is palpated by the index finger. The target area is then halfway between the rescuer’s thumb and index finger.47 Figure 30-24 shows how the syringe is kept parallel to the plane of the lower teeth and how to puncture the mucosa just medial to the rescuer’s thumbnail. When bone is contacted in the target area, the anesthetic solution is deposited. Experienced dentists miss the target area, and thus fail to produce adequate anesthesia, in approximately 10% of injections.

Dental First-Aid Kit

A more complete kit for extended expeditions should include a No. 151 universal extraction forceps (see Figure 30-13, online) and a straight elevator for extracting teeth. A mouth mirror, Orabase with benzocaine, orthodontic wax, dental floss, dental syringe, 30-gauge needles, and anesthetic cartridges complete the kit. These items fit in a small case and weigh about 14 oz. A custom dental first-aid kit is preferred over commercial dental “travel kits,” which contain unnecessary items and lack essential ones.

In an outdoor situation, techniques must often be adapted or improvised depending on the items available. For example, Figure 30-18 shows how a suture can be used to splint an avulsed or extruded tooth. A temporary filling can be fashioned from softened candle wax, an emery board can be used to smooth a sharp tooth, or a pocket knife can be used to perform a drainage procedure.

Prevention

Helmets are essential for preventing trauma in rock climbing, whitewater kayaking, and mountain biking. It is estimated that custom-made mouth guards prevent over 200,000 injuries every year in interscholastic sports.34 Their use in backcountry recreation, now almost nonexistent, would probably prevent many dental injuries if used in appropriate circumstances. Despite commercial claims to the contrary, there is no scientific evidence that mouth guards can prevent traumatic brain injury.18

1 Ahovus-Saloranta D. Antibiotics for acute maxillary sinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2008;139:486.

2 American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. Information statement. http://www.aaos.org/about/papers/advistmt/1033.asp.

3 American Association of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgeons. Position paper on bisphosphonate-related osteonecrosis of the jaws. September 25 http://www.aaoms.org/docs/position_papers/osteonecrosis.pdf, 2006.

4 Andreasen JO, Andreasen FM. Essentials of traumatic injuries to the teeth, ed 2. St Louis: Mosby; 2000.

5 Anonymous. Battlefield advanced trauma life support. J Roy Army Med Corp. 2002;148:270.

6 Antonelli JR. Acute dental pain: I. Diagnosis and emergency treatment. Compendium. 1990;11:492.

7 Aubertin MA, Horbelt C, Wasson W, et al. Medication use in geriatric populations: Dental implications of frequently prescribed medications. Gen Dent. 2010;58:100.

8 Baker D, Eisen D. Valacyclovir for prevention of recurrent herpes labialis: 2 double-blind, placebo-controlled studies. Cutis. 2003;71:239.

9 Bender IB. Pulpal pain diagnosis: A review. J Endodont. 2000;26:175.

10 Blank LW. Clinical guidelines for managing mandibular dysfunction. Gen Dent. 1998;46:592.

11 Bridgeman A, Wisenfeld D, Newland S. Major maxillofacial infections: An evaluation of 107 cases. Aust Dent J. 1995;41:281.

12 Bridgeman A, Wisenfeld D, Newland S. Anatomical considerations in the diagnosis and management of acute maxillofacial bacterial infections. Aust Dent J. 1996;41:238.

13 Chow AW. Life-threatening infections of the head and neck. Clin Infect Dis. 1992;14:991.

14 Diangelis AJ, Bakland LK. Traumatic dental injuries: Current treatment concepts. J Am Dent Assoc. 1998;129:1401.

15 Femiano F, Lanza A, Buonaiuto C, et al. Guidelines for diagnosis and management of aphthous stomatitis. Pediatr Infect Dis J.. 2007;26:728.

16 Flores MT, Andreasen JO, Bakland LK, et al. Guidelines for the evaluation and management of traumatic dental injuries. Dent Traumatol. 2001;17:193.

17 Green AW, Flower EA, New NE. Mortality associated with odontogenic infection. Br Dent J. 2001;190:529.

18 Halstead PD. The role of intraoral protective appliances in the reduction of mild traumatic brain injury. Compendium. 2009;30:18.

19 Harvey R, Hannan SA, Badia L, et al. Nasal saline irrigations for the symptoms of chronic rhinosinusitis. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2007;137:532.

20 Hile LM, Linklater DR. Use of 2-otcyl cyanoacrylate for the repair of a fractured molar tooth. Ann Emerg Med. 2006;47:424.

21 Hooley JR, Golden DP. Surgical extractions. Dent Clin North Am. 1994;38:217.

22 Kobs G, Bernhardt O, Kocher T, et al. Oral parafunctions and positive clinical examination findings. Stomatologija. 2005;7:81.

23 Kuriyama T, Williams DW, Yanagisawa M, et al. Antimicrobial susceptibility of 800 anaerobic isolates from patients with dentoalveolar infection to 13 oral antibiotics. Oral Microbiol Immunol.. 2007;22:285.

24 Laskin D. Anatomic considerations in diagnosis and treatment of odontogenic infections. J Am Dent Assoc. 1964;69:308.

25 Lausten LL, Glaros AG, Williams K. Inter-examiner reliability of physical assessment methods for assessing temporomandibular disorders. Gen Dent. 2004;52:509.

26 Markman S, Khan J, Howard J. Elusive dental pain. Gen Dent. 2010;58:e62. (serial online) http://www.agd.org/publications/gd/issues/2010/mar/pageflip.html

27 Marx RE, Sawatari Y, Fortin M, et al. Bisphosphonate-induced exposed bone of the jaws: Risk factors, recognition, prevention and treatment. J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2005;63:1567.

28 Matthew DC, Sutherland S, Basrani B. Emergency management of acute apical abscesses in the permanent dentition: A systematic review of the literature. J Can Dent Assoc. 2003;69:660a.

29 Miller CS, Cunningham LL, Lindroth JE, et al. The efficacy of valacyclovir in preventing recurrent herpes simplex virus infections associated with dental procedures. J Am Dent Assoc. 2004;135:1311.

30 Moss HD, Toscano N, Holtzclaw D. Recognition and management of odontogenic referred pain. Gen Dent. 2009;57:388.

31 National Institutes of Health. Management of temporomandibular disorders: National Institutes of Health technology assessment conference statement. J Am Dent Assoc. 1996;127:1595.

32 Okeson JP. Bell’s orofacial pains, ed 5. Chicago: Quintessence; 1995.

33 Okeson JP, editor. Orofacial pain: Guidelines for assessment, diagnosis and management, ed 4. Quintessence, Carol Stream, Ill, 2008;55.

34 Padilla R, Dorney B, Balidov S. Prevention of oral injuries. Can Dent Assoc J. 1996;24:30.

35 Powell SL, Robertson L, Doy BJ. Dental nerve blocks: Toothache remedies for the acute care setting. Postgrad Med. 2000;107:229.

36 Ram D, Cohenca N. Therapeutic protocols for avulsed permanent teeth: Review and clinical update. Pediatr Dent. 2004;26:251.

37 Ratcliff S, Becker IM, Quinn L. Type and incidence of cracks in posterior teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 2001;86:168.

38 Ruggiero SL, Gralow J, Marx RE, et al. Practical guidelines for the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of osteonecrosis of the jaw in patients with cancer. J Clin Oncol Prac. 2006;2:7.

39 Sands T, Pynn BR, Katsikeris N. Odontogenic infections: Microbiology, antibiotics, and management. Oral Health. 1995;85:11.

40 Sarlani E, Balciunas B, Grace EG. Orofacial pain: I. Assessment and management of musculoskeletal and neuropathic causes. AACN Clin Issues. 2005;16:333.

41 Shabahang S. American Association of Endodontics Research and Scientific Affairs Committee: State of the art and science of endodontics. J Am Dent Assoc. 2005;136:41.

42 Shankland WE. Temporomandibular disorders: Standard treatment options. Gen Dent. 2004;54:349.

43 Spruance SL, Jones TM, Blatter MM, et al. High-dose, short-duration, early valacyclovir therapy for episodic treatment of cold sores: Results of two randomized, placebo-controlled multicenter studies. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2003;47:1072.

44 St Pierre SA, Bartlett BL, Schlosser BJ. Practical management measures for patients with recurrent herpes labialis. Skin Therapy Lett. 2009;14:1.

45 Svirsky JA. Recurrent aphthous ulcerations. Va Dent J. 1992;69:8.

46 Swift JQ, Gulden WS. Antibiotic therapy: Managing odontogenic infections. Dent Clin North Am. 2002;46:623.

47 Trebus DL, Singh G, Meyer RD. Anatomical basis for inferior alveolar nerve block. Gen Dent. 1998;46:632.

48 Trope M. Clinical management of the avulsed tooth: Present strategies and future directions. Dent Traumatol. 2002;18:1.

49 Tulli T, Hacht O, Hohlrieder M, et al. Dentofacial trauma in sport accidents. Gen Dent. 2002;50:274.

50 Wilson W, Taubert KA, Gewitz M, et al. Prevention of infective endocarditis: Guidelines from the American Heart Association—A guideline from the American Heart Association Rheumatic Fever, Endocarditis and Kawasaki Disease Committee, Council on Cardiovascular Disease in the Young, and the Council on Clinical Cardiology, Council on Cardiovascular Surgery and Anesthesia, and the Quality of Care and Outcomes Research Interdisciplinary Working Group. J Am Dent Assoc. 2008;139:3S.

51 Yagiela JA. Recent developments in local anesthesia and oral sedation. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2004;25:697.

52 Zambito RF, Zambito ML. Exodonture: Technique and art. NY State Dent J. 1992;58:33.