Chapter 1 Why focus on risk?

Clinical risk assessment should be motivated primarily by the intention to provide a patient with better treatment and care.1

This book is designed to assist clinical practice by providing the knowledge and skills to apply sound risk management techniques in day-to-day work. The purpose of applying these risk management techniques is to provide better outcomes for patients, staff and the community. The risk management processes contained in this book aim to ensure that all reasonable steps to promote wellbeing and provide adequate safeguards against avoidable harm have been taken during a patient’s treatment and care. Understanding and pursuing the assessment (and management) of risk to oneself and others is part of the required standard of ordinary clinical practice.2 This book is primarily a clinical guide, but can also be used as a teaching tool.

Principles of risk management

Much medical effort goes into managing the risks of complications of disease processes rather than managing the symptoms of the disease itself. Hypertension is the classic example, with no symptoms but plenty of treatments, all aiming to reduce the risk of complications such as strokes and myocardial infarctions. Psychiatry’s misfortune has been to choose diseases where the complications … are homicide, suicide or reduced capacity for self-care and vulnerability.4

This problem becomes the nub of risk management within mental health. On the one hand clinicians try to treat the illness while at the same time managing the risk, which is often a complication of the disease process rather than a symptom of the disease itself. ‘Risk, especially violence, can be a preventable complication of some types of mental disorder.’5

Risk to others

• Guidelines for the Assessment and Management of Risk to Others, 2006. Available from www.tepou.co.nz/page/tepou_23.php

• Violence: The short-term management of disturbed/violent behaviour in inpatient psychiatric settings and Emergency Departments (EDs). Available from National Institute of Clinical Excellence: http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG/Published

Self-harm

• Australasian Self-harm Guidelines. Summary in Australasian Psychiatry, 2003 (11)2: 150–5.

• Guidelines for the Management of Deliberate Self-harm in Young People. Available from Australasian College of Emergency Medicine and Royal Australian and New Zealand College of Psychiatrists.

• Self-harm: The Short-Term Physical and Psychological Management and Secondary Prevention of Self-harm in Primary and Secondary Care. Available from National Institute of Clinical Excellence: http://www.nice.org.uk/Guidance/CG/Published

This book is only one step in learning about risk assessment and management. Further steps include:

• Implementing the clinical skills learned and gaining familiarity with the process of risk assessment and management. Being unfamiliar with a task can increase the likelihood of error by a factor of 17.6

• Team and individual support through team meetings, seeking advice from a senior colleague, supervision, audits, reviews, second opinions, etc.

The development of a risk culture within mental health services

In the 1960s insurance companies in the United States coined the phrase ‘risk management’8 and around the same time an increasing number of medical lawsuits led to insurance companies applying the same concepts to the health sector.9 Over the last 50 years there has been a movement towards greater accountability for all professionals and a parallel movement of consumer empowerment. Litigation and complaints have continued to become an ever-present component of clinical practice whilst the culture of blame in which we live has become more pronounced.10

Political focus and media commentary on (risk) have increased. Society has become, in general, more risk averse.11 Across all media, people with a mental disorder are portrayed in a negative manner, and typically as dangerous.12 The pendulum may be swinging, however, with calls for the culture of blame to be given up.13 Some clinicians feel that they work in a riskier environment but it may be that this is a response to increased scrutiny and accountability of their work. Consumer empowerment and access to information has allowed patients to become more aware of treatment options and more able to demand the best quality of care available. This change should be welcomed. Clinicians have had to adapt to this new environment: some have been more successful than others. Some clinicians may be more defensive in their practice as a result of anxiety driven by a fear of accountability and a fear of complaints being laid against them. ‘The effects of this (blame) culture appear to be counterproductive, leading to defensive practice, and undermining both professional morale and recruitment into the profession.’14

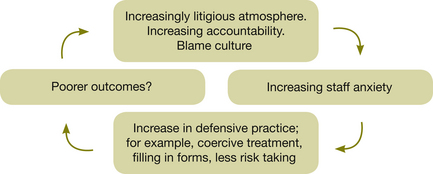

Clinicians may think they are in the vicious circle outlined in Figure 1.1.15

The blame culture is unlikely to change in the near future. Clinicians are increasingly accountable, which is appropriate, but if increased accountability is allowed to heighten anxiety, clinical practice will be stifled.

The danger of frequent legislative changes, and a growing emphasis on blame attribution when things go wrong, is that professionals can feel that they lack expertise in implementing unfamiliar procedures or using new terminology. It is important to remember that the basic standards of good clinical practice have changed very little and adherence to them will avoid most pitfalls.16

Out of concern about the ‘blame culture’, Carson (2008)17 developed proposals which were to be understood as an integrated program for tackling blame culture. The evidence and theory to support these proposals were presented in a recent book by Carson and Bain (2008).18

Carson’s proposals for tackling the blame culture are outlined below. He says they are self-evident ‘truths’ about risk-taking, and are generally agreed with by professional associations and employers. As this should improve staff morale, and reduce the risk of litigation, employers ought to embrace these principles.19

• Risk is part of life so by definition, it is inevitable that harm will sometimes occur, irrespective of the quality of risk decisions and risk management.

• The quality of a risk decision cannot properly be impugned just because harm resulted. Equally a risk decision should not be assumed good just because no harm occurred. And failure to make any necessary decision may be the cause of harm, and deserves censure.

• When judging a risk decision, both the risk assessment and risk management should be considered, including the quantity and quality of resources made available for the latter.

• By definition, risk assessment involves imperfect knowledge and risk management involves finite resources.

• Risk assessment inevitably involves difficult decisions about values. That others would have made different decisions does not, on its own, indicate that a poor or improper decision was made.

• Anyone, including managers, supervisors, systems designers and employers (i.e. not only those in the front line) can be the cause of poor risk decision-making, such as where insufficient or inappropriate support, advice, information, training or other resources are provided.

• If risk-taking is to improve then there must be an analysis of good decision-making, not just inquiries where harm results. People will learn more useful lessons from what works than from what does not work.

• There can be no liability for negligence if the risk decision did not cause loss.

• If a clinician made a poor risk decision, but the harm would have happened anyway because of other factors, there is no liability in the law of negligence. (However, an inquiry, or disciplinary hearing, would still be entitled to condemn the decision-maker as the inquiry needs to consider the quality of the decision.)

• The most important requirement for the law of negligence is that the risk decision was one which no responsible body of co-professionals would have made. A judge has to decide what is professionally acceptable. The ready availability of clear, current, professionally endorsed standards and values should reduce litigation. If complainants can readily observe that the standards and practices involved in their cases were consistent with contemporary practice, they are less likely to risk being sued.20 The benchmark was defined in Bolam v Friern Hospital [1957] 2 All ER 118;1 WLR 582: ‘A doctor is not guilty of negligence if he has acted in accordance with a practice accepted as proper by a responsible body of medical men skilled in that particular art’.21

• Risk management facilitates a pro-active approach.

• Through risk management clinicians are better prepared for crises.

• Loss of control is less likely through risk management.

• Adverse outcomes can be better prepared for.

• Risk management assists in better utilisation of resources.

• Best practice within resource limitations is possible through risk management.

• Positive outcomes from reviews and inquiries are more likely when using risk management.

1 Mullen P.E. Dangerousness, risk and the prediction of probability. In: New Oxford Textbook of Psychiatry. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2001.

2 Winestock M. Risk assessment: ‘a word to the wise’. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 1996;2:3–9.

3 Carson D. Developing models of risk to aid cooperation between law and psychiatry. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health. 1996;6:6–10.

4 Maden A. Violence risk assessment: the question is not whether but how. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2005;29:121–122.

5 Maden A. Treating Violence: a Guide to Risk Management in Mental Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press; 2007.

6 Williams J. A database method for assessing and reducing human error to improve operational performance. In: Hagen W., ed. ILEEE Fourth Conference on Human Factors and Power Plants. New York: Institute for Electrical and Electronic Engineers; 1988:200–231.

7 Snowden P. Practical aspects of clinical risk assessment and management. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170(suppl 32):32–34.

8 Matthews R. Healthcare Risk Management in Dental Practice. Healthcare Risk Management Bulletin. 1992;4:7–8.

10 Szmukler G. Blame culture, risk assessment: ‘numbers’ and ‘values’. Psychiatric Bulletin. 2003;27:205–207.

11 Royal College of Psychiatrists 2008 Rethinking Risk to Others in Mental Health Services. Final report of a scoping group. Royal College of Psychiatrists Report CR 150, June.

12 Rose D., Knight M., Fleischmann P., et al. Scoping Study: Public and Media Perceptions of Risk to General Public Posed by Individuals with Mental Ill Health. Service User Research Enterprise (SURE). London: Kings College; 2007.

13 Morgan JF 2007 Giving up the Culture of Blame. Briefing Document for the Royal College of Psychiatrists, February.

15 Adapted fromHarrison G. Risk assessment in a climate of litigation. British Journal of Psychiatry. April 1997;170(Suppl):37–39.

17 Carson D. Justifying risk decisions. Criminal Behaviour and Mental Health (Editorial). 2008;18:139–144.

18 Carson D., Bain A.J. Professional Risk and Working with People: Decision-making in Health, Social Care and Criminal Justice. London: Jessica Kingsley; 2008.

21 Harrison G. Risk assessment in a climate of litigation. British Journal of Psychiatry. 1997;170(Suppl):37–39. April