Whiplash-associated disorders

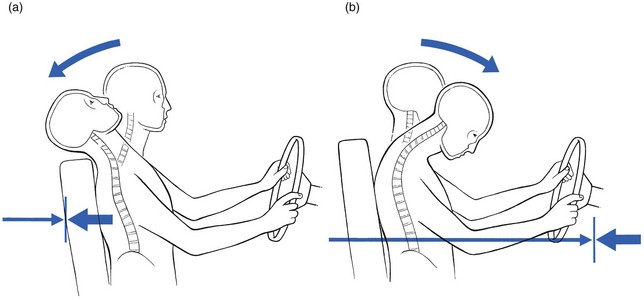

When a vehicle is struck from the rear, the occupants rarely have any warning and do not brace the muscles to prevent head movement. As a result, the body is propelled forwards and the neck hyperextends backwards well beyond the normal range of allowable movement (Fig. 10.1). This violent motion is followed by a less rapid forwards recoil into flexion that can often result in a head injury if the head impinges on the windscreen.

Definition

Medical literature, in an attempt to find a proper definition, has so far described ‘whiplash injury’ in terms of the mechanism of the accident, the type of lesion that is caused or the clinical appearance after the injury. In 19951 the Quebec Task Force (QTF) proposed the following definition:

Incidence

The incidence is not precisely known. A figure of 1 per 1000 people per year has been suggested.2

Other studies in Canada mention 5000 whiplash cases a year in the province of Quebec, accounting for 20% of all insurance claims after motor vehicle accidents.3,4

In the United States 11 300 000 car accidents were reported for the year 1991, of which 2 690 000 were rear-end collisions and caused 85% of all whiplash injuries.5

Classification

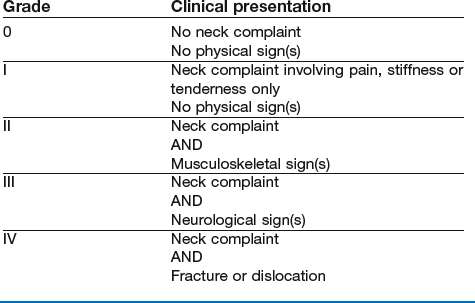

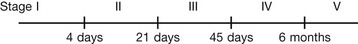

The QTF, persuaded that proper diagnosis is difficult to achieve, has proposed two classifications: one according to the severity of the symptoms and signs (grades) (Box 10.1) and one according to the time elapsed since the accident (stages) (Box 10.2).

Pathology

Depending on the movement of the head during the accident, several lesions may occur, ranking from severe to moderate to slight. Hyperextension is the most common mechanism, followed by hyperflexion and lateral flexion.6

Severe lesions

Hyperextension and distraction of the neck may rupture the anterior longitudinal ligament as well as some discs. A ruptured disc can lead to backward displacement of the vertebra lying above it – the upper facets then slide downwards on the lower – with damage to the spinal cord as a result.7 Spinal cord injuries after motor vehicle accidents occur most often in young car users in the 15–24 year age group.8,9

Hyperflexion injury may lead to fractures of the vertebral body – most fractures of the atlas10 and of the axis11 are the result of motor vehicle accidents – and/or to disruption of posterior ligaments and occasionally facet joint luxation.

Other lesions

Discodural and discoradicular interactions

Recent retrospective studies have shown that the occurrence of disc lesions after whiplash injury is quite high12,13 and one prospective study indicates the value of clinical diagnosis.14 Most disc lesions are endplate avulsions and ruptures of the anterior annulus fibrosus.

As the result of the hyperextension element during the trauma the disc may have fissured. The subsequent flexion or hyperflexion element causes displacement of disc material in a posterior direction. Davis et al describe a number of posterolateral disc lesions with radicular symptoms as the result of a hyperextension whiplash trauma.12 These herniations seemed to develop only after the acute phase and it took a few weeks for the radicular symptoms to appear. In postmortem studies Taylor et al describe the intervertebral disc as the most frequently damaged structure.15–17 Jónsson et al18 Also confirmed the large number of disc lesions after whiplash, and during surgery were able to confirm the findings from magnetic resonance imaging (MRI).

Posterocentral protrusions lead to central, bilateral or unilateral pain in a multisegmental distribution: pain in the neck, trapezius and upper scapular area. On examination a symmetrical (mimicking a full articular pattern) or asymmetrical pattern of limitation is found. In acute cases the picture may be torticollis-like. For a detailed description of disc pathology, see page 145.

Facet joint problems

Whiplash may also lead to problems at the level of the zygapophyseal joint capsules.19 Lord et al undertook a placebo-controlled prevalence study after whiplash and found that chronic cervical facet joint pain was common.20

Pain is felt unilaterally and is usually quite localized. A convergent or divergent motion pattern may occur, although any asymmetrical pattern is compatible. (Facet joint pathology is discussed on p. 163).

Ligamentous lesions

Ligaments can become overstretched, leading to minor lesions,12 or may become adherent as the result of post-traumatic immobilization. They present with vague stretching pain felt at the end of range of those movements that stretch the ligament (see p. 168).

Muscular lesions

Muscular lesions, mostly anteriorly, are described in clinical studies,21,22 on echography,23 in experiments in animals24,25 and in postmortem studies.26 Muscles, particularly their occipital insertions, can be strained during injury. The subsequent pain will be quite localized and can be elicited during either contraction or stretching – the contractile tissue pattern (see p. 169).

Medicolegal consequences

The different parties involved in the approach to WAD are:

• The patient who is seeking help and a refund of money. For most patients the two elements do not influence each other but for a number of people the compensation claim is essential. This may result in absence from work, illness behaviour, social disability, malingering and fraud.

• Doctors who are looking for a diagnosis. Physicians treating the patient wish to reach a diagnosis and to confirm it with technical investigations. They also – because of the often-complex nature of the syndrome – use an extensive pattern of treatment techniques. Doctors who work for the insurance company are sometimes biased and tend to over-diagnose the condition as ‘psychogenic’ or ‘simulation’.

• Insurance companies who are trying to minimize their payments. As the result of the lack of consensus about diagnosis and treatment of WAD, insurance companies see their compensation payments and indemnities rise considerably. They exert pressure on governments in order to keep these expenses under control.

• Lawyers who are protecting either the insurance company or the patient. Discussions about confirmation of the lesions and the consequences for patients’ professional activities lead to an increase in litigation.

It is clear that eligibility for compensation for pain and suffering furthers the perseverance of symptoms and a tendency to chronicity. Where this compensation can be eliminated, a decrease in incidence and an improved prognosis are seen.27

Psychological problems

Most WAD start as an ordinary trauma followed by purely physical disturbance. When subsequent treatment is unable to rehabilitate the patient after a short period of time, secondary emotional and psychological changes may supervene. They raise the patient’s awareness of neck pain and subsequently aggravate and perpetuate the pain, or even turn a simple neckache into chronic pain and disability.28

Diagnosis

Clinical picture

Technical investigations in post-traumatic neck patients are mandatory but the decision as to which imaging technique to use should be based on clinical grounds. Radiographs in patients with soft tissue injuries are often negative: no fractures or luxations are found. The finding most commonly obtained is loss of the normal cervical curvature on a lateral view.29 CT and MRI are not very helpful in recent cases but may become important when the condition persists, although their use is still controversial. Scintigraphy may be useful to screen for occult fractures.30

The reader is referred to the section on non-discogenic disorders (see Ch. 9) for further information about the diagnosis of non-mechanical conditions.

Symptoms

The examiner should enquire about the mechanism and velocity of the trauma so that a judgement can be made about the severity of the injury and so that a prognosis can be reached.31 Other important information relates to the time interval between the accident and the onset of symptoms, which often is 2–3 days.32 Many patients have associated low back pain33 and this is noted and assessed later.

Signs

Articular signs – pain on movement with or without limitation – suggest involvement of the intervertebral joint or the facet joints, certainly when movement is shown to be restricted. Discodural or discoradicular interactions are considered when articular signs are accompanied by dural or radicular signs (see p. 145). When there is no dural or nerve root involvement, the possibility of a condition involving the facet joint exists; the pain is purely unilateral, i.e. when either a convergent or a divergent pattern is found. Limitation of movement indicates that the joints are responsible.

End-range pain is typical of ligamentous or muscular conditions, the latter also giving rise to positive resisted movements (see p. 169).

Because combined lesions are not at all uncommon, the clinical picture may become difficult and therefore hard to interpret. It should be looked at in the light of the anatomical findings and compared to the clinical pictures known to occur in the cervical spine (see Ch. 8).

Natural history

The natural history of WAD is difficult to predict. An extensive study in Switzerland found that 30% of patients still complained of symptoms, even 4–7 years after the accident.34 Another study showed that increasing age and the severity of the initial neck pain were predictors of lasting symptoms after 6 months.35 Objective neurological signs and degenerative changes on radiographs or MRI (spondylosis, diminution of the diameter of the spinal canal) may be associated with a poor prognosis.

Chronicity

Not all patients will develop chronic symptoms after whiplash injury. In most instances it is a benign, self-limiting condition. All patients destined to recover will do so in the first 2–3 months after trauma. Those who do not may claim symptoms for several more years. Recent studies have indicated that between 14 and 42% of patients develop chronic symptoms and that about 10% have permanent difficulties,36–42 although patients may improve even after many years.43 A predisposing factor for chronicity could be pre-existing spondylosis.44

In those countries where the entity of ‘chronic pain’ resulting from rear-end collisions is not known and consequently there is no fear of long-term disability leading to indemnity and litigation, symptoms after whiplash injury are self-limiting, lasting for only a short period of time, and there is no evolution towards the chronic stage.45

Therapeutic approach

Such an approach is also recommended by the QTF in order to avoid prolonged disability.46 An early return to work is advocated as one of the best measures to avoid chronicity. Immobilizing measures such as bed rest and collars are best avoided.

Specific treatment

When a discal pattern is found and thus a discodural or discoradicular interaction is present, manipulation is performed immediately because it is unwise to leave the displacement untreated; posterocentral protrusions draw out osteophytes fairly quickly, and this may lead to a situation in which extension or one rotation becomes permanently blocked. Because a posterocentral protrusion is present, great care must be taken in the choice of techniques and operation; rotation movements are avoided and the therapist must be experienced. In acute cases with gross deviation, manipulation is performed every day. Traction in the direction of the deviation, followed by pure traction manipulations without articular movement, quickly leads to full recovery. The more moderate and long-standing cases require more treatments, performed once or twice a week over a few weeks. The techniques for posterocentral protrusions are used: straight pull, lateral flexion, anteroposterior gliding and traction with leverage (see p. 201).

Facet joint lesions can be treated either with steroid infiltration or with deep transverse massage; in more chronic cases slow stretching is used (see p. 201).

References

1. Scientific Monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Spine. 1995; 20(8S):22S.

2. Barnsley, L, Lord, S, Bogduk, N, Whiplash injuries. Pain 1994; 58:283–307. ![]()

3. Girard N. Statistiques descriptives sur la nature des blessures. Québec: Régie de l’assurance automobile du Québec, Direction des services médicaux et de la réadaptation, April. Internal Document, 1989.

4. Giroux, M. Les Blessures à la colonne cervicale: importance du problème. Le Médecin du Québec. 1991; Sept:22–26.

5. Van Goethem, JWM, Biltjes, IGGM, van den Hauwe, L, et al, Whiplash injuries: is there a role for imaging? Eur J Radiol 1995; 22:8–14. ![]()

6. Hohl, M. Soft-tissue neck injuries. In: Sherk HH, ed. The Cervical Spine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott; 1989:436–441.

7. Kinoshita, H, Pathology of hyperextension injuries of the cervical spine. Paraplegia 1994; 32:367–374. ![]()

8. Northrup, BE. Evaluation and early treatment of acute injuries to the spine and spinal cord. In: Clark CR, ed. The Cervical Spine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:541–549.

9. Myers, BS, McElhaney, JH. Cervical Spine Injury Mechanisms. Biomechanics and Prevention. New York: Springer; 1993.

10. Kurz, LT. Fractures of the first cervical vertebra. In: Clark CR, ed. The Cervical Spine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:409–413.

11. Clark, CR, White, AA, III., Fractures of the dens: a multicenter study. J Bone Joint Surg 1985; 67A:1340–1348. ![]()

12. Davis, S, Teresi, L, Bradley, W, et al, Cervical spine hyperextension injuries: MR findings. Radiology 1991; 180:245–251. ![]()

13. Hamer, AJ, Gargan, MF, Bannister, GC, Nelson, RJ, Whiplash injury and surgically treated cervical disc disease. Injury 1993; 24:549–550. ![]()

14. Pettersson, K, Hildingsson, C, Toolanen, G, et al, Disc pathology after whiplash injury. A prospective magnetic resonance imaging and clinical investigation. Spine. 1997;22(3):283–287. ![]()

15. Taylor, JR, Finch, PM, Neck sprain. J Aust Fam Physician 1993; 22:1623–1629. ![]()

16. Taylor, JR, Twomey, LT, Acute injuries to cervical joints: an autopsy study of neck sprain. Spine. 1993;18(9):1115–1122. ![]()

17. Taylor, JR, Twoney, LT, Disc injuries in cervical trauma. Lancet 1991; 338:1340–1343. ![]()

18. Jónsson, H, Jr., Cesarini, K, Sahlstedt, B, Rauschning, W, Findings and outcome in whiplash-type neck distorsions. Spine 1994; 19:2733–2743. ![]()

19. Ketroser, DB, Whiplash, chronic neck pain, and zygapophyseal joint disorders. A selective review. Minn Med J. 2000;83(2):51–54. ![]()

20. Lord, SM, Barnsley, L, Wallis, BJ, Bogduk, N, Chronic cervical zygapophysial joint pain after whiplash. A placebo-controlled prevalence study. Spine. 1996;21(15):1737–1745. ![]()

21. Frankel, VH. Pathomechanics of whiplash injuries to the neck. In: Morley TP, ed. Current Controversies in Neurosurgery. Philadelphia: Saunders; 1996:39–50.

22. Jeffreys, E. Soft tissue injuries of the cervical spine. In: Disorders of the Cervical Spine. London: Butterworth; 1980:81–89.

23. Martino, F, Ettore, GC, Cafaro, E, et al, L’Ecographia musculo-tendinea nei traumi distorvi acuti del collo. Radiol Med Torino 1992; 83:211–215. ![]()

24. Macnab, I, Whiplash injuries of the neck. Manitoba Med Rev 1966; 46:172–174. ![]()

25. La Rocca, H, Acceleration injuries of the neck. Clin Neurosurg 1978; 25:209–217. ![]()

26. Jónsson, H, Jr., Bring, G, Rauschning, W, Sahlstedt, B, Hidden cervical spine injuries in traffic accident victims with skull fractures. J Spinal Discord 1991; 4:251–263. ![]()

27. Cassidy, JD, Carroll, LJ, Coté, P, et al, Effect of eliminating compensation for pain and suffering on the outcome of insurance claims for whiplash injury. NEJM. 2000;342(16):1179–1186. ![]()

28. Waddell, G. The Back Pain Revolution. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone; 1998.

29. Daffner, RH, Evaluation of cervical injuries. Sem Roentgenol 1992; 27:239–253. ![]()

30. Kitchel, SH. Soft-tissue neck injuries. In: Clark CR, ed. The Cervical Spine. 3rd ed. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1998:351–355.

31. Gebhard, JS, Donaldson, DH, Brown, CW, Soft tissue injuries of the cervical spine. Orthop Rev. 1994;(Suppl 1):9–17. ![]()

32. Jolliffe, VM, Soft tissue injury of the cervical spine: consider the nature of the accident. BMJ 1993; 307:439–440. ![]()

33. Taylor, JR, Finch, PM, Neck sprain. Aust Fam Physician 1993; 22:1623–1625. ![]()

34. Dvorak, J, Valach, L, Schmidt, S. Cervical spine injuries in Switzerland. J Manual Med. 1989; 4:7–16.

35. Radanov, BP, di Stefano, G, Schnidrig, A, Ballinari, P, Role of psychosocial stress in recovery from common whiplash. Lancet 1991; 338:712–715. ![]()

36. Hodgson, SP, Grundy, M. Whiplash injuries: their long-term prognosis and its relationship to compensation. Neuro-Orthop. 1989; 7:88–91.

37. Hildingsson, C, Toolanen, G, Outcome after soft-tissue injury of the cervical spine. A prospective study of 93 car-accident victims. Acta Orthop Scand 1990; 61:357–359. ![]()

38. Pettersson, K, Kärrholm, J, Toolanen, G, Hildingsson, C, Decreased width of the spinal canal in patients with chronic symptoms after whiplash injury. Spine. 1995;20(15):1664–1667. ![]()

39. Barnsley, L, Lord, S, Bogduk, N, Clinical review. Whiplash injury. Pain 1994; 58:283–307. ![]()

40. Maimaris, C, Barnes, MR, Allen, MJ, ‘Whiplash injuries’ of the neck: a retrospective study. Injury 1988; 19:393–396. ![]()

41. Gargan, MF, Bannister, GC, Long-term prognosis of soft-tissue injuries of the neck. J Bone Joint Surg 1990; 72B:901–903. ![]()

42. Olsson, I, Bunketorp, O, Carlsson, G, et al. An in-depth study of neck injuries in rear end collisions. In: Proceedings of the International IRCOBI Conference on the Biomechanics of Impacts. France: Bron-Lyon; 1990:269–280.

43. Olivegren, H, Jerkvall, N, Hagstrom, Y, Carlsson, J, The long-term prognosis of whiplash-associated disorders (WAD). Eur Spine J. 1999;8(5):366–370. ![]()

44. Bonuccelli, U, Paverse, N, Lucetti, C, et al, Late whiplash syndrome: a clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Functional Neurol. 1999;14(4):219–225. ![]()

45. Obelieniene, D, Schrader, H, Bovim, G, et al, Pain after whiplash: a prospective controlled inception cohort study. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 1999;66(3):279–283. ![]()

46. Scientific Monograph of the Quebec Task Force on Whiplash-Associated Disorders. Spine. 1995; 20(8S):36S.