5 When to test for Helicobacter pylori and what to do with a positive test

Case

A 47-year-old executive consults you because his older brother, aged 61, has recently been diagnosed with gastric cancer. The patient advises you he wants to have testing for the stomach bacteria that causes gastric cancer. The patient is asymptomatic and in particular has no history of epigastric pain, fullness after meals, early satiety, vomiting, weight loss, dysphagia or gastrointestinal bleeding. He is a non-smoker. No other family members have been affected by gastric cancer to his knowledge. The patient was born in Australia to parents of British descent. The patient has been taking low-dose aspirin for cardiovascular health reasons, but has not been taking non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. He has no known drug allergies. Physical examination is completely normal.

After a full discussion, the patient still wishes to go ahead with testing.

Pathogenesis

H. pylori is most often acquired in childhood by close contact with other infected families and, once acquired, persists for life in most cases. The mode of transmission is probably oral (via saliva or vomit) and, in the developing world, faecal spread. Virtually 100% of infected individuals develop gastritis; the lifetime risk of peptic ulcer disease in those infected is approximately 20%.

Management Guidelines

Testing for H. pylori infection

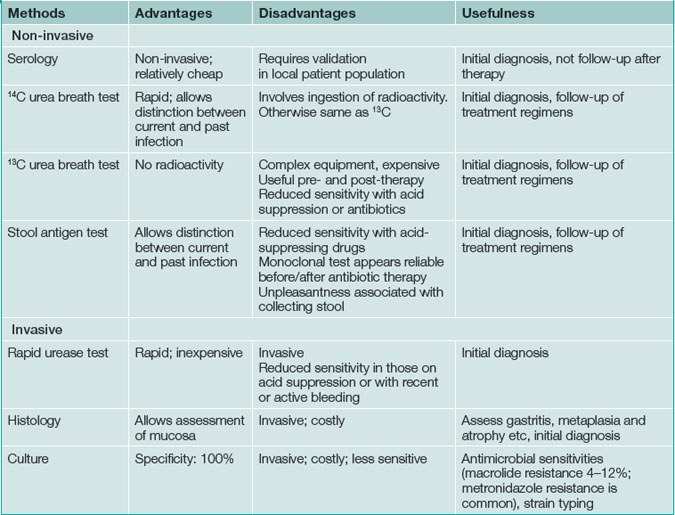

Testing for H pylori infection should be performed only if the clinician plans to offer treatment to patients with a positive result (Box 5.1). The advantages and disadvantages of tests for H. pylori are summarised in Table 5.1.

Non-invasive (non-endoscopic) tests

Serology (laboratory enzyme-linked immuno-sorbent assay [ELISA]) is widely available and relatively inexpensive but is not the test of choice in most circumstances. Serologic testing can determine whether a patient has had H. pylori infection in the past, but cannot definitively identify the presence of current infection. A positive result may be obtained even after the infection has cleared. The sensitivity and specificity are about 80%; consequently, serology risks missing approximately one of every five cases of H. pylori infection or, conversely, administering unnecessary treatment to patients who are no longer infected.

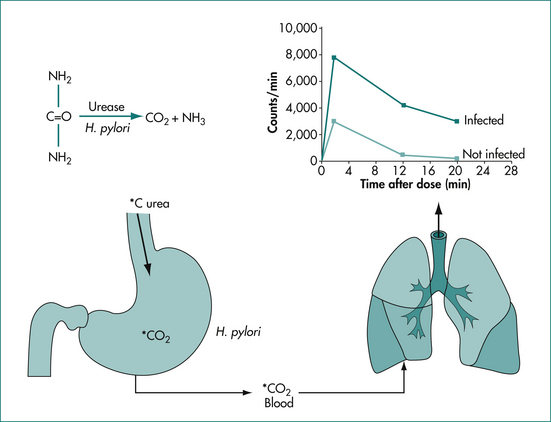

Urea breath testing is an excellent non-invasive method of assessing the presence of H. pylori via the urease activity of the organism (Fig 5.1). In a patient with infection, the patient ingests urea labelled with either the isotope 13C (which is non-radioactive) or the isotope 14C (using a low dose so there is low radioactivity). If infection is present, there is breakdown of the urea via urease produced by the bacteria; the excessive labelled carbon dioxide produced can be quantified in expired breath. The 14C test is contraindicated in pregnant women and children. This technique offers excellent positive and negative predictive values, regardless of the background prevalence of H. pylori. Moreover, the test is useful both before and after treatment. Accurate results are also more often achieved in the setting of upper-gastrointestinal bleeding with this test. Sensitivity is reduced by medications such as proton pump inhibitors, bismuth and antibiotics, which decrease the H. pylori density on which the test is based. Patients should be off acid suppression medications for at least 1 week before testing by the urea breath test for infection if possible; if the test is negative and the patient is or recently has been on acid suppression drugs, testing with an alternative method or repeating the test later should be considered.

Endoscopic tests

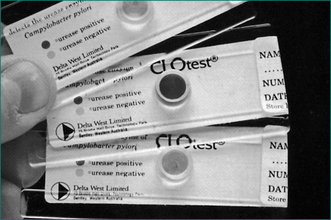

H. pylori infection can be diagnosed at endoscopy by a screening test, the rapid urease test, which has a high sensitivity and specificity (over 95%) (Fig 5.2). It involves placing a biopsy in a pH-sensitive medium containing urea. Urease produced by the bacteria splits the urea to ammonia that changes the pH and produces a colour change. The various commercially available biopsy urease tests have comparable diagnostic accuracy, with excellent specificity (93% to 100%) and very good sensitivity (89–98%). It should be noted, however, that the sensitivity is reduced in patients who have taken proton pump inhibitors within the preceding 1–2 weeks. In addition, biopsy testing may yield false-negative results in patients with ulcers that are actively bleeding, and therefore all bleeding ulcer patients should be re-evaluated, preferably using urea breath testing if initially biopsy tests for the infection are negative.

Gastric histology offers excellent sensitivity and specificity, but is much more costly than biopsy urease testing. Moreover, the accurate detection of H. pylori depends on the site, number, and size of gastric biopsies. To optimise the diagnostic yield, multiple biopsy samples should be obtained from both the antrum and gastric body. All samples can be placed into a single container to reduce costs. As in the case of biopsy urease testing, the sensitivity of histology is decreased in the presence of proton pump inhibitor therapy such that the diagnosis of H. pylori infection will probably be missed in more than one-third of patients. The main advantages of this technique are its ability to check for pathological changes associated with infection (such as atrophy or intestinal metaplasia) and to diagnose mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) lymphoma. Usually, the gastroenterologist will take samples for histology if there is cause for concern based on the visual findings or if a gastric ulcer is present.

Treatment

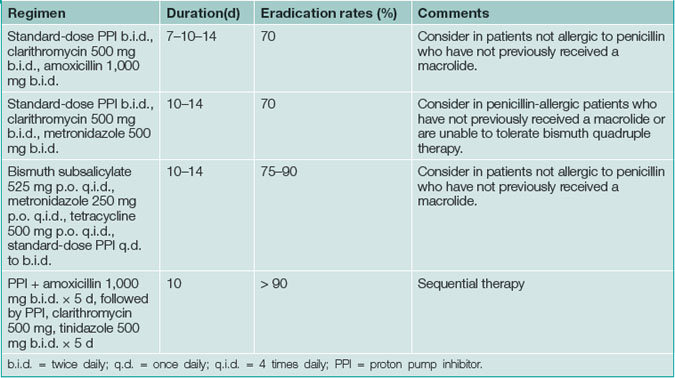

All patients must be tested for H. pylori infection prior to prescribing specific treatment. Suppression of H. pylori is easy with a single antibiotic but unhelpful; eradication (i.e. cure) of infection is essential. Therapy for H. pylori first line consists of acid suppression plus antibiotics in most cases, as this approach is synergistic (Table 5.2).

Compliance with treatment is key to success but side effects can limit adherence (Table 5.3). Patients should be warned about potential side effects and to call before stopping therapy. Among the most serious side effects is C. difficile colitis, which is rare.

Table 5.3 Most common side effects related to H. pylori treatments

| Treatment | Most common side effects |

|---|---|

| PPIs | Headache, diarrhoea |

| Clarithromycin | GI upset, diarrhoea, altered taste, C. difficile colitis |

| Amoxicillin | GI upset, headache, diarrhoea, C. difficile colitis |

| Metronidazole | Metallic taste, dyspepsia |

| Tetracycline | GI upset, photosensitivity, tooth discoloration |

| Bismuth compounds | Darkening of tongue/stool, nausea, GI upset |

GI = gastrointestinal; PPI = proton pump inhibitor.

Integrating H. pylori testing and treatment into clinical practice

Treatment failure

If two attempts to treat the infection fail, specialist consultation is advised. Culture of the organism and testing for antibiotic sensitivities may be considered. Salvage treatment regimens include (1) a 10-day course of a standard dose of proton pump inhibitor, amoxicillin (1 g), and levofloxacin (250 mg), all given twice daily, or (2) a proton pump inhibitor twice daily, rifabutin (300 mg once daily), and amoxicillin (1 g twice daily) for 10 days.

Key Points

Chey W.D., Wong B.C.Y. Practice Parameters Committee of the American College of Gastroenterology. American College of Gastroenterology guideline on the management of Helicobacter pylori infection. Am J Gastroenterol. 2007;102:1808-1825.

Ford A., Talley N.J. Does H elicobacter pylori really cause duodenal ulcers? Yes. BMJ. 2009;339:b2784.

Laine L., Estrada R., Trujilo M., et al. Effect of proton-pump inhibitor therapy on diagnostic testing for Helicobacter pylori. Ann Intern Med. 1998;129:547-550.

Loy C.T., Irwig L.M., Katelaris P.H., et al. Do commercial serological kits for Helicobacter pylori infection differ in accuracy? A meta-analysis. Am J Gastroenterol. 1996;91:1138-1144.

Talley N.J., Fock K.M., Moayyedi P. Gastric Cancer Consensus conference recommends Helicobacter pylori screening and treatment in asymptomatic persons from high-risk populations to prevent gastric cancer. Am J Gastroenterol. 2008;103:510-514.

Zullo A., Gatta L., De Francesco V., et al. High rate of Helicobacter pylori eradication with sequential therapy in elderly patients with peptic ulcer: a prospective controlled study. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2005;21:1419-1424.