37 When to Refer/Mohs Surgery

When to Refer

Clinicians should not be hesitant to perform a skin biopsy. Multiple methods are available (see Chapters 8 through 11). Complications are so rare, and the benefits are so great, that all clinicians, especially those in primary care, should consider mastering this skill. If one wants to limit procedural acumen solely to skin biopsies, then referral would be necessary for many findings. However, the average primary care clinician should be able to evaluate and treat 95% of all dermatologic conditions that come into the office using the techniques described in this text. Cryotherapy, electrosurgery, injection techniques, laceration repair, and simple incisions/excisions will be adequate to treat the majority of conditions. When the excisions become larger and more complicated, it is then that many patients may need to be referred.

Other, More Rare and Potentially Aggressive Cancers

The following are examples of when most primary care clinicians might consider a referral1–6:

Mohs Surgery

Mohs surgery is a technique in which careful mapping of a lesion (usually an NMSC) is performed using marking dye at the time of the removal.7,8 The lesion is excised and immediately processed histologically. Areas of residual tumor are identified under the microscope by the Mohs surgeon and further excision completed in the specific areas needed. It is generally performed in an office under local anesthesia. The advantage is that the entire tumor can be removed with cure rates as high as 99%. The disadvantages are the time and costs to perform the procedure. Most reviews have found it to be cost effective for high-risk cancers. Potential indications for Mohs are noted in Box 37-1. Medicare will cover reimbursement for Mohs micrographic surgery for the diagnoses and indications listed in Box 37-2.

Box 37-1

Indications for Mohs Micrographic Surgery in Patients with High-Risk Skin Cancers

Source: Adapted from National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers. Version 1.2010. Accessed online April 13, 2010, at http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nmsc.pdf.

Box 37-2 Medicare Covers Reimbursement for Mohs Surgery for these Diagnoses

Patient Selection

Examples of patients that were referred for Mohs surgery including those with the following lesions:

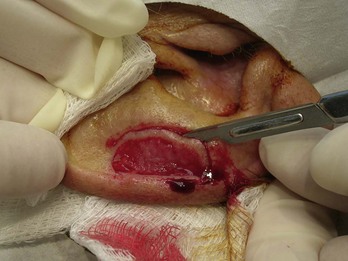

Performing Mohs Surgery

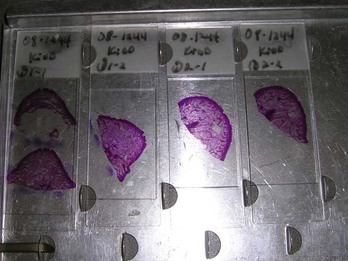

FIGURE 37-9 Mohs slides in the tray ready to be viewed under the microscope.

(Copyright Richard P. Usatine, MD.)

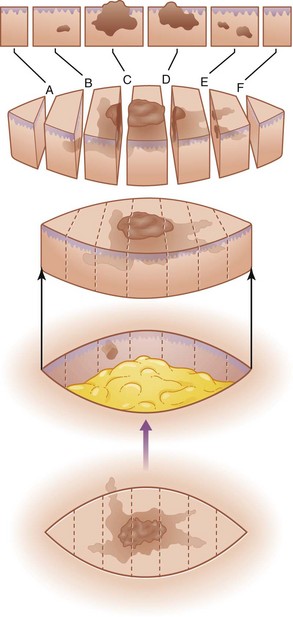

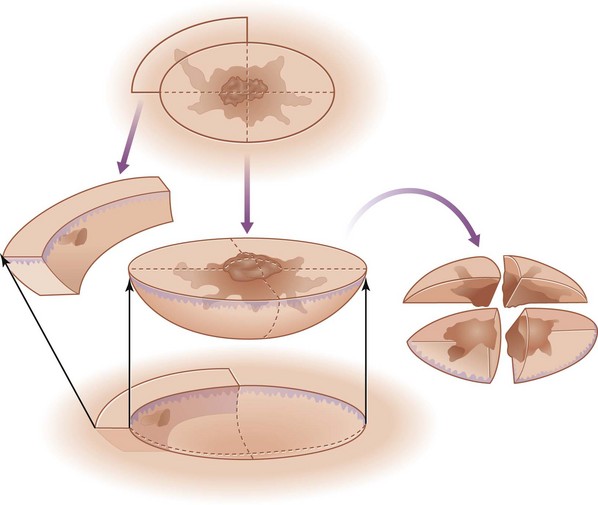

Standard pathology for an ellipse involves bread loaf examination of the tissue (Figure 37-10). Mohs surgery is done with a more complete examination of the margin (Figure 37-11).

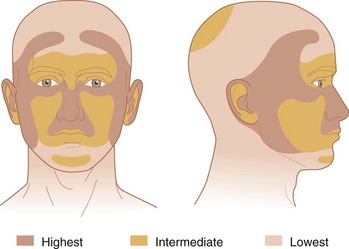

One way to consider who to refer is to look at Figure 37-12 of the H-zone and the levels of recurrence risk. The H-zone resembles the letter “H” and is the highest risk area.

1. Evidence-Based Clinical Practice Guidelines: Treatment of Cutaneous Melanoma. Arlington Heights, IL: American Society of Plastic Surgeons, May 2007.

2. Guidelines of care for cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma: Committee on Guidelines of Care. Task Force on Cutaneous Squamous Cell Carcinoma. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1993;28(4):628.

3. Motley R, Kersey P, Lawrence C. Multiprofessional guidelines for management of the patient with primary cutaneous squamous cell carcinoma. Br J Dermatol. 2002;146:18-25.

4. Stulberg DL, Crandell B, Fawcett RS. Diagnosis and treatment of basal cell and squamous cell carcinoma. Am Fam Physician. 2004;70:1481-1488.

5. National Comprehensive Cancer Network. Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Basal Cell and Squamous Cell Skin Cancers. Version 1 http://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/PDF/nmsc.pdf, 2010. Accessed online April 18, 2010, at

6. Habif T. Clinical Dermatology: A Color Guide to Diagnosis and Therapy, 4th ed. Philadelphia: Mosby; 2004.

7. Bowen GM, White GL, Gerwels JW. Mohs micrographic surgery. Am Fam Physician. 2005;72:845-848.

8. Shriner DL, McCoy DK, Goldberg DJ, Wagner RF. Mohs micrographic surgery. J Am Dermatol. 1998;39:79-97.