Chapter 87 When Should a Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty Be Considered?

The first unicompartmental knee arthroplasty (UKA), the Polycentric, was released in 1968 by Gunston,1 after which UKA became a viable treatment option for selected patients with unicompartmental osteoarthritis. Initial results for UKA in the 1970s were somewhat unimpressive, perhaps suggestive of the learning curve associated with the introduction of a novel technology.2 After publication of improved UKA results in the 1980s and continued refinement of patient selection, technology, and surgical procedure, Kozinn and Scott3 published what have now become referred to as the “classic” indications for UKA.4 These inclusion and exclusion criteria were selected for an elderly, nonobese patient with noninflammatory medial compartment arthritis and intact ligaments. Although an important and widely quoted publication, the development of the classic indications for UKA was largely based on observational series often using survivorship as the sole outcome metric. Survivorship of UKA demonstrated equivalent survivorship in the first decade between UKA and total knee arthroplasty (TKA), but worse survivorship for UKA in the second decade. Thus, UKA was initially seen as a definitive procedure that would not need to be revised in an elderly patient.

Interest in UKA has been renewed since the 1990s associated with newer designs and minimally invasive surgery (MIS).5 This renewed interest may also be associated with the unmet burden of middle-aged patients with unicompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee.6 Without the underpinnings of strong evidenced-based indications, UKA is increasingly being recommended as a bridging procedure for younger patients with isolated osteoarthritis of the medial or lateral compartment,7 in addition to a definitive procedure in the older patient. Furthermore, some authors have expanded the indications to include patients with anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) deficiency and patients with significant patella-femoral arthritis. The variability and lack of consensus of indications for UKA have led to a reported range of potential candidates for UKA in a knee arthroplasty population of between 5% and 30%.8 Despite the fact that UKA preceded TKA and the renewed interest in UKA, the cumulative revision rates for UKA have not improved in Sweden since the 1970s. This is in distinction to TKA, which has seen a significant reduction in cumulative revision rate (CRR) over the same period.

OPTIONS

Proximal tibial osteotomy has similar indications for a UKA, including lack of significant flexion contracture with intact range of motion. The results generally demonstrate 80% survivorship at 5 years and 60% survivorship at 10 years.10 The result, however, is often cosmetically unsatisfying and questions remain regarding the results of salvage procedures after UKA, such as TKA.11 The traditional method, and that with the most evidence, is the closing wedge osteotomy, as described by Coventry.12 Opening wedge osteotomy and opening wedge hemicallostosis osteotomy have become increasing popular.13,14 Although long-term data are lacking, the techniques are appealing in that they tend to be more “physiologic” with respect to joint biomechanics because the osteotomy is usually performed below the tubercle, and they have been suggested to be more reproducible and reduce the incidence of adverse effects such as reversed tibial slope, intra-articular fracture, patellar baja, and medial proximal tibial overhang with metaphyseal-diaphyseal mismatch11,15 (Level of Evidence IV). Proximal tibial osteotomy is generally reserved for younger patients with higher levels of demand (Level of Evidence V).

TKA has similar or better survivorship to UKA in the first decade and better survivorship in the second decade.16,17 As such, TKA is more reliable and is appropriate for older patients who may outlive their UKA. TKA has similar satisfaction rates to medial UKA (82%).18 TKA has the major advantage over UKA of being able to accommodate major ligament releases and resections, including the ACL and PCL, as well as significant bone resection to address deformity. The survivorship of TKA is adversely affected by younger age and obesity.19–22

Fresh osteochondral allografting has been recommended for the treatment of large focal defects. Matched osteochondral surfaces are transplanted from the donor to the recipient host, often with an unloading osteotomy. Reasonable success rates have been reported, but this technique has limitations in that it requires immunosuppressive drugs, carries the risk for disease transfer, and requires a large catchment area to find suitable donors.23,24 This technique has had limited success at a few centers around the world. Chondral transplant has been advocated for focal defects in one of the femoral condyles.25–27 Although it has been possible to grow chondrocytes in vitro, results of transplanted chondrocytes have been mixed because of the large biomechanical forces to which the immature chondral cells are exposed.

Arthroscopic debridement of the knee for unicompartmental arthroplasty has been shown in general to be ineffective28 (Level of Evidence I). However, evidence suggests that arthroscopic debridement can relieve symptoms temporarily for patients with mechanical symptoms, such as catching or locking, associated with arthritis28 (Level of Evidence I).

EVIDENCE

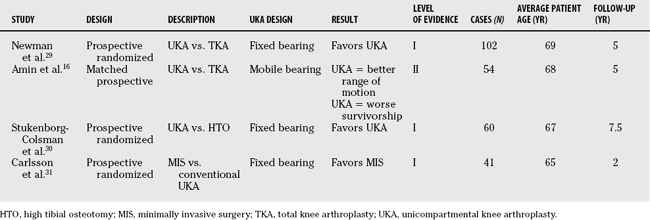

Unfortunately, UKA studies in the literature with high levels of evidence are limited (Table 87-1). In a randomized trial, Newman and colleagues29 compared 52 TKAs with 50 fixed-bearing UKAs. All patients were selected for surgery as candidates for UKA using the classic indications of intact cruciate ligaments: “normal” other compartments, flexion deformity less than 15 degrees, and varus/valgus less than 15 degrees. The mean age at surgery was 69 years. Patients in the UKA group had less morbidity, shorter length of stays, and better range of motion both in the short and the long term (109.3 vs. 102.6 degrees). Two failures occurred in the UKA group and one in the TKA group, with an additional pending failure. The number of knees able to flex greater than 120 degrees was proportionally greater in the UKA group. Pain relief was similar in both groups using the Bristol Knee Score. The authors conclude that UKA gives better results than TKA at 5 years in patients who meet the conservative criteria for UKA (Level of Evidence I).

TABLE 87-1 Summary of Studies with Levels of Evidence Greater Than II for Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

Amin and coworkers16 report on a matched study of 54 consecutive UKAs compared with 54 consecutive TKAs. The two groups of patients were matched for age, sex, body mass index, preoperative range of movement, and preoperative Knee Society scores. The mean follow-up period was 59 months in both groups. Classic selection criteria were used for the UKA group. The UKA was mobile bearing. The survivorship for the UKA group at 5 years was 88% compared with 100% for the TKA group. Subjective outcomes were similar for both groups. The range of motion was greater for the UKA group. This study differed from Newman and colleagues’29 work in that the patients with TKA were not candidates for UKA, and the UKA was mobile bearing (Level of Evidence III).

Stukenborg-Colsman and investigators30 completed a prospective, randomized trial comparing UKA with proximal tibial osteotomy. The selection criteria for the patients were medial unicompartmental osteoarthritis, varus malalignment less than 10, flexion contraction less than 15 degrees, minimal ligament instability, and age older than 60 years. The osteotomies were performed according to Coventry’s12 technique and the UKAs were fixed bearing. Thirty-two patients received osteotomies and 28 received UKAs with mean follow-up period of 7.5 years. The UKA group had fewer intraoperative and postoperative complications, had a greater percentage of patients with good or excellent results on the Knee Society Score, and had a better 7- to 10-year survivorship rate of 77% compared with 60%. The authors conclude that UKA offered better long-term results compared with Coventry-type proximal tibial osteotomy in patients older than 60 years (Level of Evidence I).

UKA has experienced a resurgence in interest since the last 1990s partly because of its adaptability to MIS. Despite the popularity of MIS, most data to support its use are anecdotal or of a low quality of evidence. Furthermore, reported MIS results are most often associated with a specific implant of interest, hence the results may not be generalizable to all implant/instrument types. Carlsson and coauthors31 have reported on the only randomized trial comparing a conventional approach in 20 patients with MIS in 21 patients, using a fixed-bearing UKA. Patients were selected for the study who had intact ligaments and unicompartmental disease; however, moderate patella-femoral arthritis was accepted. Average patient age was 64 years, and the length of follow-up was 2 years. Patients receiving the MIS approach had significantly shorter hospital stays (3 vs. 6 days). However, the subjective outcomes (Hospital for Special Surgery Score) were the same for both groups, as were the clinical outcomes such as alignment and range of motion. Precise and accurate radiostereometric analysis (RSA) data demonstrated similar migration patterns in both patients, suggesting that the long-term survivorship should be the same for both groups (Level of Evidence I).

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Acceptable Degree of Patella-Femoral Joint Arthritis

Classic indications for UKA suggest that rest pain in the patella-femoral joint is a relative contraindication to UKA, whereas asymptomatic patella-femoral arthritis is not. However, full-thickness cartilage lesions in the patella-femoral groove have been suggested to be a contraindication to surgery.3 Some authors more recently have suggested that significant patella-femoral arthritis, including that associated with pain, is not a contraindication.32 No randomized trials published to date address this issue.

Obesity

Previous literature suggests that UKA should be avoided in obese patients.3 More recent articles have refuted this notion, which appears to be based on anecdote and the expectation that increased body mass index will lead to increased load on a small area of tibia. Tabor and coauthors33 report that on a 20-year follow-up of UKA, the survivorship of the UKAs in the obese group was actually better than the nonobese group, whereas Berend and Lombardi32 report increased failures in a retrospective review (Level of Evidence II). Few data address differences in functional outcome between the two groups.

Mobile versus Fixed Bearing

Early failure patterns in UKA treatment included delamination and failure of the polyethylene bearing. Partly in an effort to address this, a more congruent but mobile-bearing polyethylene was developed. In a small, randomized trial to look at this issue, Li and researchers34 randomized 56 UKAs to a fixed-bearing versus a mobile-bearing device. In their study, the mobile-bearing knees had better kinematics, a lower incidence of radiolucency, but no difference in multiple subjective outcome questionnaires at 2 years34 (Level of Evidence II). The increased incidence of radiolucent lines is significant but difficult to interpret because radiolucent lines do not necessarily correlate with failure. Also, other that one being mobile bearing and the other fixed, the two designs of knees studied were quite disparate, and these differences in design may just as easily account for the improved kinematics. Emerson and coauthors35 report on 50 matched mobile-bearing UKAs with 51 fixed-bearing UKAs with 7.7 years of follow-up. The mobile-bearing group demonstrated a survivorship rate of 99% at 11 years, whereas the fixed-bearing group had a rate of 93%. However, the two groups had significantly different postoperative alignment, forcing the authors to conclude that the results could be attributable to surgical technique and prosthesis design (Level of Evidence III). Gleeson9 reports on the early results of a prospective study comparing 47 mobile-bearing UKAs with 57 fixed bearings. At 2 years, the mobile-bearing group had a greater failure rate, mostly because of polyethylene dislocation, and better subjective pain scores (Level of Evidence II). According to the Swedish Knee Registry,20 mobile-bearing UKAs have a greater rate of mechanical failures but a lower rate of failure for polyethylene wear than do fixed-bearing designs36 (Level of Evidence III).

Lateral Compartment Unicompartmental Knee Arthroplasty

Considerable debate is included in the literature regarding UKA of the lateral compartment. Initially, before tricondylar knee systems, it was not uncommon to use a UKA for lateral joint disease.37 In a nonrandomized, consecutive series comparing lateral with medial UKAs in 159 knees, the authors conclude that lateral UKA is a viable alternative to TKA (Level of Evidence III). However, in a large series investigating satisfaction after UKA and TKA in more than 29,000 patients from the Swedish Knee Registry, satisfaction rates after lateral UKA were significantly lower than for medial UKA18 (Level of Evidence III). Because of significant differences in the kinematics between the medial and lateral compartments, some authors have recommended caution when using meniscal bearings in the lateral compartment38,39 (Level of Evidence V).

Anterior Cruciate Ligament Deficiency

ACL deficiency has been defined in the early literature as a contraindication for UKA3 (Level of Evidence V). The concern has been that ACL laxity can ultimately culminate in increased polyethylene wear because of the altered joint kinematics, particularly with anteroposterior translation.40,41 Both favorable and unfavorable results have been reported with UKA in patients with ACL deficiency.41 ACL reconstruction at the same time as UKA has been reported in a matched series of 15 patients receiving UKA with ACL reconstruction and 15 patients receiving UKA with an intact ACL. Similar excellent short-term outcomes were reported for both groups42 (Level of Evidence III).

GUIDELINES

No published guidelines are specific to patient selection for UKA from any of the major international orthopedic or arthritis care organizations. The “classic” indications for UKA have been described by Kozinn and Scott,3 and have generally been accepted by the orthopedic community as such. However, the “classic” indications are not necessarily believed to be the contemporary indications.

UKA in younger patients has shown favorable outcomes in selected series. These series are usually from high-volume UKA knee surgeons, often with advanced knowledge of the prosthesis in question. As such, it is difficult to extrapolate the results to the larger surgical community. The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Registry has reported that in the experience of all surgeons living in one nation using multiple prostheses design and techniques, the survivorship of UKA in patients younger than 60 years is worse than in those older than 6019 (Level of Evidence III). UKA eventually will fail in the younger patient population, and it is unclear as to the survivorship of revised UKA relative to TKA. Based on the available evidence, UKA should be used judiciously in obese and highly active patients (grade C). Reports of good outcomes in UKA with ACL reconstruction and significant arthritic changes in the patella-femoral joint tend to be prosthetic specific from expert UKA surgeons. I do not recommend the routine use of UKA in these circumstances (grade C).

Given that a volume effect has been reported on more technically demanding implants, such as mobile-bearing designs,43 the casual UKA surgeon should strongly consider simpler designs with larger incisions, if necessary (grade C). Ideally, potential UKA patients would be referred to a small enough number of surgeons with a particular interest in UKA to take maximum advantage of the surgical learning curve, and ensure greater consistency and reproducibility in patient selection.

A significant need exists for appropriate studies with high levels of evidence to address the areas of controversy and to further define who are the best candidates for UKA. Table 87-2 provides a summary of recommendations.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

| A | 29 | |

* Classic indications: isolated medial compartment osteoarthritis, flexion deformity less than 15 degrees, varus/valgus less than 15 degress, intact anterior cruciate ligament

1 Gunston FH. Polycentric knee arthroplasty. Prosthetic simulation of normal knee movement. J Bone Joint Surg. 1971;53:272-277.

2 Scott RD. Unicondylar arthroplasty: Redefining itself. Orthopedics. 2003;26:951-952.

3 Kozinn SC, Scott R. Unicondylar knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:145-150.

4 Scott RD, Santore RF. Unicondylar unicompartmental replacement for osteoarthritis of the knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63:536-544.

5 Meek RM, Masri BA, Duncan CP. Minimally invasive unicompartmental knee replacement: Rationale and correct indications. Orthop Clin N Am. 2004;35:191-200.

6 Canadian Institute for Health Information. Canadian Joint Replacement Registry (CJRR) 2006 Report—Hip and Total Knee Replacements in Canada. Toronto Ontario: Canadian Institute for Health Information, 2006.

7 Price AJ, Dodd CA, Svard UG, Murray DW. Oxford medial unicompartmental knee arthroplasty in patients younger and older than 60 years of age. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2005;87:1488-1492.

8 Mont MA, Stuchin SA, Paley D, Sharkey PF, Parvisi J, et al. Different surgical options for monocompartmental osteoarthritis of the knee: High tibial osteotomy versus unicompartmental knee arthroplasty versus total knee arthroplasty: Indications, techniques, results, and controversies. Instruc Course Lect. 2004;53:265-283.

9 Gleeson RE, Evans R, Ackroyd CE, Webb J, Newman JH. Fixed or mobile bearing unicompartmental knee replacement? A comparative cohort study. Knee. 2004;11(5):379-384.

10 Naudie D, Bourne RB, Rorabeck CH, Bourne TJ. The Install Award. Survivorship of the high tibial valgus osteotomy. A 10- to 22-year follow-up study. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 367; 1999; 18-27.

11 Windsor RE, Insall JN, Vince KG. Technical considerations of total knee arthroplasty after proximal tibial osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1988;70:547-555.

12 Coventry MB. Osteotomy of the upper portion of the tibia for degenerative arthritis of the knee. A preliminary report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47:984-990.

13 Amendola A, Fowler PJ, Litchfield R, Kirkley S, Clatworthy M. Opening wedge high tibial osteotomy using a novel technique: Early results and complications. J Knee Surg. 2004;17:164-169.

14 Weale AE, Lee AS, MacEachern AG. High tibial osteotomy using a dynamic axial external fixator. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 382; 2001; 154-167.

15 Insall J, Salvati E. Patella position in the normal knee joint. Radiology. 1971;101:101-104.

16 Amin AK, et al. Unicompartmental or total knee arthroplasty? Results from a matched study. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;451:101-106.

17 Scott RD, Cobb AG, McQueary FG, Thornhill TS. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. Eight- to 12-year follow-up evaluation with survivorship analysis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 271; 1991; 96-100.

18 Robertsson O, Dunbar M, Pehrsson T, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Patient satisfaction after knee arthroplasty: A report on 27,372 knees operated on between 1981 and 1995 in Sweden. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:262-267.

19 Harrysson OL, Robertsson O, Nayfeh JF. Higher cumulative revision rate of knee arthroplasties in younger patients with osteoarthritis. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 421; 2004; 162-168.

20 Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register. Annual Report 2006—The Swedish Knee Arthroplasty Register 2006. Lund, Sweden: Department of Orthopedics, Lund University Hospital, 2006.

21 Gillespie GN, Porteous AJ. Obesity and knee arthroplasty. Knee. 2007;14:81-86.

22 Amin AK, Clayton RA, Patton JT, Gaston M, Cook RE, Brenkel IJ. Total knee replacement in morbidly obese patients. Results of a prospective, matched study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:1321-1326.

23 Gross AE, Shasha N, Aubin P. Long-term followup of the use of fresh osteochondral allografts for posttraumatic knee defects. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 435; 2005; 79-87.

24 Maury AC, Safir O, Heras FL, Pritzker KP, Gross AE. Twenty-five-year chondrocyte viability in fresh osteochondral allograft. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2007;89:159-165.

25 Gillogly SD, Myers TH, Reinold MM. Treatment of full-thickness chondral defects in the knee with autologous chondrocyte implantation. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther. 2006;36:751-764.

26 Lahav A, Burks RT, Greis PE, Chapman AW, Ford GM, Fink BP. Clinical outcomes following osteochondral autologous transplantation (OATS). J Knee Surg. 2006;19:169-173.

27 Steinwachs M, Kreuz PC. Autologous chondrocyte implantation in chondral defects of the knee with a type I/III collagen membrane: A prospective study with a 3-year follow-up. Arthroscopy. 2007;23:381-387.

28 Bradley JD, Heilman DK, Katz BP, Gsell P, Wallick JE, Brandt KD. Tidal irrigation as treatment for knee osteoarthritis: A sham-controlled, randomized, double-blinded evaluation. Arthritis Rheum. 2002;46:100-108.

29 Newman JH, Ackroyd CE, Shah NA. Unicompartmental or total knee replacement? Five-year results of a prospective, randomised trial of 102 osteoarthritic knees with unicompartmental arthritis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:862-865.

30 Stukenborg-Colsman C, Wirth CJ, Lazovic D, Wefer A. High tibial osteotomy versus unicompartmental joint replacement in unicompartmental knee joint osteoarthritis: 7-10-year follow-up prospective randomised study. Knee. 2001;8:187-194.

31 Carlsson LV, Albrektsson BE, Regner LR. Minimally invasive surgery vs conventional exposure using the Miller-Galante unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: A randomized radiostereometric study. J Arthroplasty. 2006;21:151-156.

32 Berend KR, Lombardi AVJr. Liberal indications for minimally invasive oxford unicondylar arthroplasty provide rapid functional recovery and pain relief. Surg Technol Int. 2007;16:193-197.

33 Tabor OBJr, Tabor OB, Bernard M, Wan JY. Unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: Long-term success in middle-age and obese patients. J Surg Orthop Adv. 2005;14:59-63.

34 Li MG, Yao F, Joss B, Ioppolo J, Nivbrant B, Wood D. Mobile vs. fixed bearing unicondylar knee arthroplasty: A randomized study on short term clinical outcomes and knee kinematics. Knee. 2006;13:365-370.

35 Emerson RHJr, Hansborough T, Reitman RD, Rosenfeldt W, Higgins LL. Comparison of a mobile with a fixed-bearing unicompartmental knee implant. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 404; 2002; 62-70.

36 Lewold S, Goodman S, Knutson K, Robertsson O, Lidgren L. Oxford meniscal bearing knee versus the Marmor knee in unicompartmental arthroplasty for arthrosis. A Swedish multicenter survival study. J Arthroplasty. 1995;10:722-731.

37 Lewold S, Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lidgren L. Revision of unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: Outcome in 1,135 cases from the Swedish Knee Arthroplasty study. Acta Orthop Scand. 1998;69:469-474.

38 Robinson BJ, Rees JL, Price AJ, Beard DJ, Murray DM, OHKG. Oxford Hip and Knee Group. A kinematic study of lateral unicompartmental arthroplasty. Knee. 2002;9:237-240.

39 Robinson BJ, Rees JL, Price AJ, Beard DJ, Murray DW, McLardy Smith P, Dodd CA. Dislocation of the bearing of the Oxford lateral unicompartmental arthroplasty. A radiological assessment. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2002;84:653-657.

40 Suggs JF, Li G, Park SE, Steffensmeier S, Rubash HE, Freiberg AA. Function of the anterior cruciate ligament after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty: An in vitro robotic study. J Arthroplasty. 2004;19:224-229.

41 Engh GA, Ammeen D. Is an intact anterior cruciate ligament needed in order to have a well-functioning unicondylar knee replacement?. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 428; 2004; 170-173.

42 Pandit H, Beard DJ, Jenkins C, Kimstra Y, Thomas NP, Dodd CA, Murray DW. Combined anterior cruciate reconstruction and Oxford unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88:887-892.

43 Robertsson O, Knutson K, Lewold S, Lidgren L. The routine of surgical management reduces failure after unicompartmental knee arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83:45-49.