Chapter 46 What Is the Role of Splinting for Comfort?

External immobilization is used in three situations: the provisional (and sometimes the definitive) nonoperative treatment of unstable bone and soft-tissue injuries, the treatment of stable bone and soft-tissue injuries, and after surgical fracture or soft-tissue stabilization.

Unstable injuries involve bone or soft-tissue discontinuity to the extent that the pieces move independently with minimal force. Immobilizing unstable limb injuries is a basic principle of emergency fracture management designed to decrease pain and to minimize additional soft-tissue damage and hemorrhage. Provisional immobilization of unstable injuries may be followed by surgical intervention or definitive nonoperative treatment. External immobilization such as casting for the definitive treatment of unstable injuries usually requires that at least one adjacent joint near the injury is immobilized to prevent displacement during healing. When the decision is made to treat an unstable injury (e.g., a displaced tibia fracture) without surgery, the deleterious effects of joint immobilization,1 such as muscle atrophy, weakness, and joint stiffness, are generally unavoidable. For unstable injuries, some form of immobilization is mandatory.

EVIDENCE

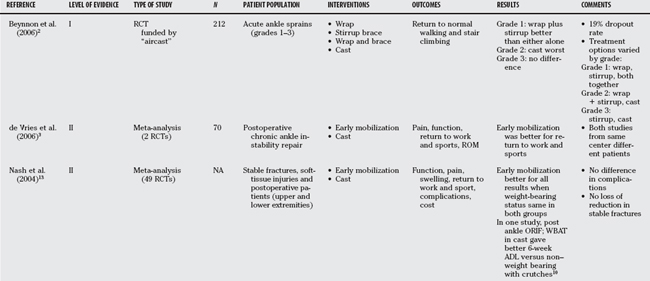

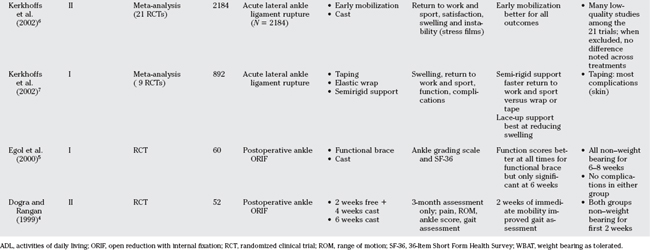

A number of randomized clinical trials of varying quality have been undertaken to address the issue of immobilization versus functional treatment for stable injuries and after open reduction and internal fixation of ankle fractures. Most of these studies have been summarized in meta-analyses (Table 46-1). Most studies have dealt with ankle injuries.2–10 Few studies have addressed upper extremity injuries.11–13

Ankle Sprain

Faster return to normal activities such as work and sport with functional mobilization versus rigid immobilization has been the most consistent finding across trials. An industry-sponsored randomized clinical trial2 (Level I) graded the degree of ankle sprain and then randomized grade 1 sprains to an elastic wrap, an ankle stirrup brace, or a combination of both2 (Fig. 46-1). Grade 2 sprains were randomized to the same groups as grade 1 sprains or a cast, and grade 3 sprains were allocated to either a stirrup brace or cast. For grade 1 sprains, the combination of an elastic wrap under an ankle stirrup resulted in a return to normal walking and stair climbing that was roughly twice as fast as either alone (4–6 vs. 10–12 weeks; P < 0.01). For grade 2 sprains, the combination of elastic wrap beneath an ankle stirrup brace was similar to a wrap alone or a brace alone, with these functional treatments all resulting in a significant decrease in the time to normal weight bearing and stair climbing versus cast immobilization (10–12 vs. 24–28 weeks; P < 0.01). There was no difference in return to these activities for grade 3 sprains treated with either stirrup bracing or cast immobilization (18–21 weeks for both groups with grade 3 sprains). When comparing the different types of functional treatments, Kerkhoff and colleagues7 note that a semirigid brace led to faster return to work (4.2 days; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 2.4–6.1 days) and sport (relative risk [RR], 9.6; 95% CI, 6.3–12.9) than an elastic bandage alone. Lace-up ankle supports were best at decreasing swelling, with elastic bandages the worst for swelling (RR, 5.5; 95% CI, 1.7–17.8). Taping led to the most skin irritations.

FIGURE 46-1 Combination of both elastic wrap and ankle stirrup brace.

(From Beynnon BD, et al: A prospective, randomized clinical investigation of the treatment of firsttime ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med 34:1401-1412, 2006, reprinted with permission of SAGE Publications.)

Kerkhoff and colleagues’ systematic review6 (Level II) reports on early mobilization with “functional treatment” versus cast immobilization for ankle sprains. Functional treatment was defined as any treatment that did not rigidly immobilize the ankle joint, but that may involve elastic wraps, braces, or other support. All patients were allowed weight bearing as tolerated. A second review compared the various forms of functional treatment7 (Level I). Return to work was faster (8.2 days; 95% CI, 6.3–10.2 days), as was return to sport (4.9 days; 95% CI, 1.5–8.3 days). Patients were also more likely to be satisfied with functional treatment (RR, 1.8; 95% CI, 1.1–3.1), and they suffered less swelling at 6 to 12 weeks of follow-up (RR, 1.7. 95% CI, 1.2–2.6). Instability on stress films was less likely at follow-up after functional treatment (RR, 2.6; 95% CI, 1.2–4.0). When only the highest quality studies were included, return to work remained significantly faster in functionally treated patients (12.9 days; 95% CI, 7.1–18.7 days).

Ankle Instability Surgery

de Vries and coauthors3 summarize the results of two studies6,7 that compared functional treatment versus immobilization after surgical repair for chronic ankle instability. Patients experienced faster return to work (1.8 days; 95% CI, 0.9–2.7 days) and earlier return to sport (3 days; 95% CI, 2–4 days) with functional treatment versus immobilization. Pain scores and Tegner function score favored functional treatment but did not reach significance.3

Ankle Fracture Fixation

The studies that address the issue of ankle fracture fixation are difficult to summarize.4,5, 10, 13 Some immobilize both groups for varying periods, and some allow weight bearing in the casted group but not the functional treatment group, and still others exclude patients with osteoporosis and questionable fixation from randomization considering these patients ineligible for potential functional treatment. Is early functional treatment safe? None of the comparisons notes an increased rate of wound problems or loss of fixation, but the study issues noted earlier demand that this result be interpreted with caution. When similar weight-bearing protocols were used in the functional and the casted group after ankle fracture fixation, there is a consistent finding of faster return to work and to function with early mobilization4,5, 13 (Level II), with no difference in function noted across treatment groups by 3 months given the available sample sizes. Egol and researchers5 note better vitality and general health scores (36-item short form [SF-36]) at 6 weeks with early functional treatment. These authors also note a significantly faster return to work in the functional group (53.8 vs. 106.5 days; P = 0.007).

Weight bearing after ankle fixation improved patient satisfaction and allowed faster return to activities of daily living10,13 (Level II). Weight bearing was accompanied by cast immobilization. A 2-week period of non–weight bearing associated with range-of-motion exercises followed by 4 weeks of weight bearing in a cast gave similar results at 3 months as 6 weeks of continuous cast immobilization, except that the gait pattern was more symmetric in the early mobilization group.4

Other Injuries

Nash and coworkers13 summarize the evidence from 49 randomized clinical trials regarding immobilization versus functional treatment for stable fractures or soft-tissue injuries and for postoperative treatment14 (Level II). Early functional treatment was not associated with displacement of stable fractures and was not associated with increased wound problems. Patients generally preferred early mobilization and experienced earlier return to work and sport, decreased pain, swelling, and stiffness.13,14

AREAS OF UNCERTAINTY

Patients generally benefit from being able to use their limbs after injury for weight bearing. Early mobility helps speed return to work and sports, and there appears to be little danger that “stable” injuries will become unstable if treated with mobilization and early function. Table 46-2 provides a summary of recommendations.

| RECOMMENDATION | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION |

|---|---|

ORIF, open reduction with internal fixation; WBAT, weight bearing as tolerated.

1 Pathare NC, et al. Deficit in human muscle strength with cast immobilization: Contribution of inorganic phosphate. Eur J Appl Physiol. 2006;98:71-78.

2 Beynnon BD, et al. A prospective, randomized clinical investigation of the treatment of first-time ankle sprains. Am J Sports Med. 2006;34:1401-1412.

3 de Vries JS, et al. Interventions for treating chronic ankle instability. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4:CD004124.

4 Dogra AS, Rangan A. Early mobiliation versus immobiliation of surgically treated ankle fractures. Prospective randomised control trial. Injury. 1999;30:417-419.

5 Egol KA, Dolan R, Koval KJ. Functional outcome of surgery for fractures of the ankle. A prospective, randomised comparison of management in a cast or a functional brace. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000;82:246-249.

6 Kerkhoffs GM, et al. Immobiliation and functional treatment for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD003762.

7 Kerkhoffs GM, et al. Different functional treatment strategies for acute lateral ankle ligament injuries in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2002;3:CD002938.

8 Margo K. The Air-Stirrup brace with elastic wrap improved function in first incident grade 1 or 2 lateral ankle ligament sprain. Evid Based Med. 2007;12:48.

9 Swiontkowski MF, et al. Interobserver variation in the AO/OTA fracture classification system for pilon fractures: Is there a problem? J Orthop Trauma. 1997;11:467-470.

10 van Laarhoven CJ, Meeuwis JD, van der Werken C. Postoperative treatment of internally fixed ankle fractures: A prospective randomised study. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:395-399.

11 Plint AC, et al. A randomized, controlled trial of removable splinting versus casting for wrist buckle fractures in children. Pediatrics. 2006;117:691-697.

12 Handoll HH, Pearce PK. Interventions for isolated diaphyseal fractures of the ulna in adults. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;2:CD000523.

13 Nash CE, et al. Resting injured limbs delays recovery: A systematic review. J Fam Pract. 2004;53:706-712.

14 Kreder HJ. Commentary: Review; early mobilisation is better than cast immobilisation for injured limbs. Evid Based Med. 2000;10:118.