Chapter 64 What Is the Relation Between Malunion and Function for Lower Extremity Tibial Diaphyseal Fractures?

Tibial diaphyseal fractures are one of the most common fractures of the long bones.1 Controversy remains, however, over the best way to manage these fractures, with authors arguing not only over operative techniques but also between surgical and nonsurgical management. With any treatment, however, one thing is agreed on, there is an inherent risk for healing with some degree of residual malalignment. Indeed, in a recent systematic review of the treatment of distal-third tibial shaft fractures, for example, incidence rates of malunion (as defined by the authors of the included studies) ranged from 13.1% to 16.2% depending on treatment choice.2

Two major issues should be considered when discussing malunion. The first is what actually constitutes a malunion; that is, what are the limits of an acceptable reduction? Second, will a malunion result in any long-term adverse sequelae to the patient? If the malunion does not cause adverse sequelae, then does it actually matter? To make the argument completely circular, is it actually a malunion, radiographic issues aside? Surgeons’ definition of angular malunion has been shown to range from less than 5 to 20 degrees, and a majority of surgeons defined significant shortening as greater than 15 mm.3 However, some would argue that asymptomatic angulation be considered an anatomic deviation rather than malunion per se.4

EVIDENCE

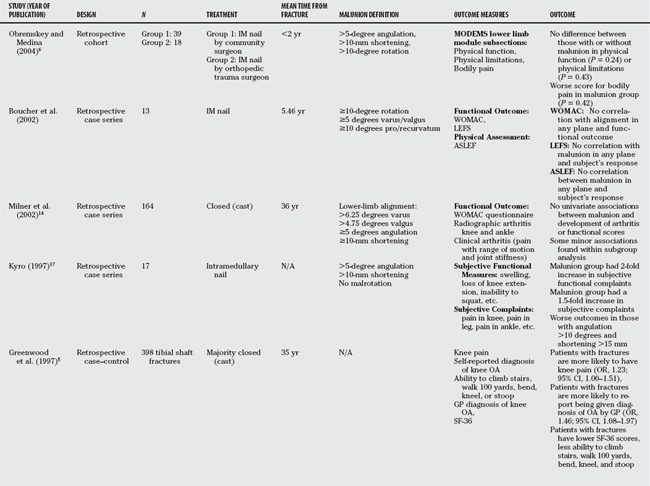

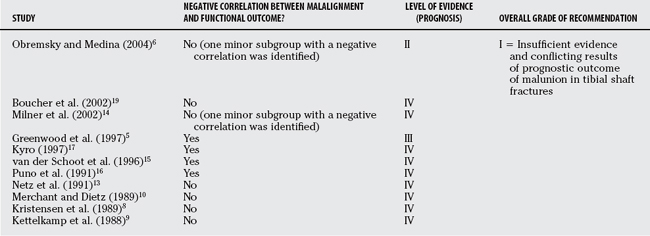

For a number of reasons, reports are conflicting regarding the effect of malunion on the long-term functional outcome after tibial shaft fractures. These include a general lack of consensus as to what constitutes a malunion, retrospective reporting with incomplete follow-up and varying times of follow-up (from 10–40 years), a lack of standardized technique to radiographically measure malunion, and the use of multiple and varied functional outcome measures between studies (some that are nonstandardized and nonvalidated) (Table 64-1).

Before assessing whether malunion of the tibial shaft affects long-term functional outcome, it is important to understand the long-term outcome in those with a tibial shaft fracture in general. Greenwood and colleagues5 retrospectively reviewed 398 patients with tibial shaft fractures (it was not stated how the fractures were all treated just that “most were treated with cast therapy”) and compared these with a cohort of 1573 age- and sex-matched control subjects.5 Outcome measures were subjective reporting of knee pain, ability to walk 100 yards, bend, kneel, and stoop, and a general practitioner’s diagnosis of osteoarthritis. The 36-Item Short Form Health Survey (SF-36) outcome instrument was also used. Greenwood and colleagues5 found that patients with a tibial shaft fracture had more knee pain (odds ratio, 1.23; 95% confidence interval [CI], 1.00–1.51) and an increase in having a diagnosis of osteoarthritis (odds ratio, 1.46; 95% CI, 1.08–1.97). They also found a statistically significant incidence of a decreased ability of the patients with fractures to climb stairs, bend, kneel, or stoop. Interestingly, even though the odds ratios themselves suggested a slightly increased risk for knee pain or diagnosis of osteoarthritis, the confidence intervals either include 1 or come close to 1, suggesting that these results are trends as opposed to true statistical differences. However, because the same trend was seen throughout all domains of the outcome measures, it may be that the study was underpowered and these trends are accurate estimates of the truth.

Malunion Does Not Affect Long-Term Functional Outcome

One retrospective cohort study was identified that attempted to correlate malunion with functional outcome6 (Level of Evidence II, retrospective cohort). In this study, two different groups of surgeons (community surgeons and orthopedic trauma surgeons) each treated a cohort of patients with an intramedullary nail. Between the groups it was demonstrated that the community surgeon group had a greater malunion rate.6 Using the Musculoskeletal Outcomes Data Evaluation and Management Scale (MODEMS) lower functional extremity score, they found no significant functional differences between those with a malunion as compared with those without within the subset scales of physical function and physical limitations. However, within the bodily function subscale, they found a slightly statistically significantly worse outcome in the malunion group (P = 0.042). This should be interpreted with caution, however, because multiple subgroup analysis may potentially result in spuriously positive findings.7 Also, this study was primarily addressing the issue of whether orthopedic trauma surgeons had less malunions and was underpowered to detect a difference comparing those with a malunion and those without.

Smaller observational case series are available that suggest that the long-term effect of malunion of tibial shaft fractures does not affect functional outcome.8–10 Merchant and Dietz10 reviewed 37 tibial fractures with a mean follow-up period of 29 years10 (Level of Evidence IV, retrospective case series). They assessed both clinical and radiographic outcome of both the knee and ankle. With the outcome scores used (Iowa knee evaluation and the Iowa knee evaluation modified by the authors for the ankle), 78% of the ankles and 92% of the knees of the study group were rated as good or excellent. With the radiographic outcome used (author derived from a synthesis of previously published scores), 76% of the ankles and 92% of the knees in the study group had a good or excellent result. When subgroup analysis was done, they found no statistically significant difference in function between those whose tibial angulation in any plane was less than 5 degrees compared with those whose angulation was 5 to 10 degrees or more than 10 degrees. Given their numbers, however, these statistical comparisons may be underpowered, potentially resulting in a beta or type II statistical error.

Kristensen and coworkers8 examined 17 patients with a tibial angular deformity of more than 10 degrees a minimum of 20 years after their injury.8 Using clinical outcome criteria according to Cedell11 and radiographic criteria according to Magnusson,12 they found no evidence of knee or ankle arthritis in their study population.8 Netz and coauthors13 reviewed their series of tibial fractures treated with cast application and found no correlation of patients’ subjective complaints, clinical examination, or muscle force analysis with angular deformity or leg-length discrepancy.13

More recently, Milner and investigators14 evaluated 167 subjects after an average follow-up period of 36 years from the initial injury. They used a validated functional outcome score (the Western Ontario and McMaster Osteoarthritis Index [WOMAC]) to assess knee function and an author-derived clinical and radiographic arthritis score. They found no significant association between the development of knee or ankle arthritis and tibial malalignment. There was, however, a trend for those limbs in varus malalignment to have more frequent evidence of medial compartment knee arthritis and for those limbs in either varus or valgus malalignment to be associated with subtalar stiffness.14

Malunion Does Affect Long-Term Functional Outcome

Observational case series have been identified that suggest that tibial malalignment does, in fact, correlate with the extent of knee or ankle arthritis and, therefore, the functional outcome of the patient. van der Schoot and coauthors15 suggest that malaligned fractures show more degenerative changes with a correlation between symptoms in the knee and radiographic arthritis.15 This correlation, however, did not hold for ankle symptoms and radiographic ankle arthritis. Puno and researchers16 assessed 28 tibial fractures correlating joint malalignment and clinical outcome. They found that greater ankle malalignment correlated with poorer clinical results. However, this correlation did not hold for malalignment about the knee. Similar results have been associated with malunions after an intramedullary nail. Kyro17 evaluated a group of 17 patients and found that those with a malunion had an increased number of subjective functional findings (such as swelling of the lower limb, loss of knee, ankle, or subtalar motion, or squatting difficulties) and subjective complaints (pain in the knee, leg, ankle or foot, swelling, and problems with walking, running, squatting or working).

ARE THE RESULTS OF THESE STUDIES VALID?

All studies are retrospective in nature, and the majority is case series reviews. This allows for the potential introduction of bias at a number of levels including a selection bias, recall bias, and measurement bias, among others. Indeed, it has been shown that observational studies can both overestimate and underestimate treatment effects.18 Between the studies, the lack of standardized and fully validated outcome measures limits the inferences that can be made. Most of the studies had a small sample size, and thus could have been underpowered to detect differences between groups (type II error). As well, some of the studies performed a number of subgroup analyses with small numbers of patients that may lead to spuriously positive findings of statistical significance suggesting that these positive results should be interpreted with caution.7

EVIDENCE-BASED BOTTOM LINE

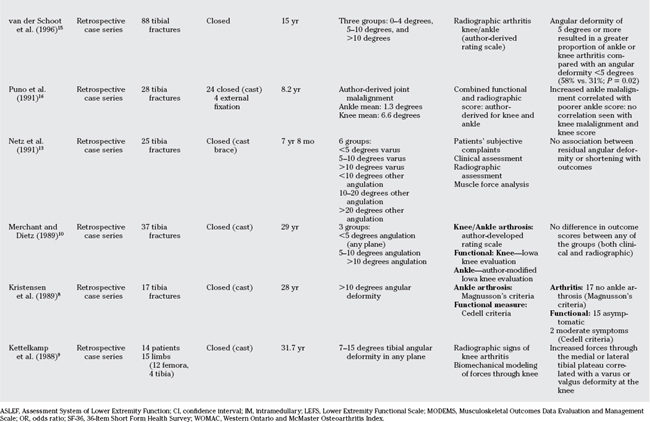

Based on the current available evidence, the following has been reported (Table 64-2):

1 Court-Brown C, McQueen MM, Tornetta PIII. Tibia and fibula diaphyseal fractures. In: Tornetta PIII, Einhorn T, editors. Trauma. Philadelphia: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006:339-353.

2 Zelle BA, Bhandari M, Espiritu M, et al. Treatment of distal tibia fractures without articular involvement: A systematic review of 1125 fractures. J Orthop Trauma. 2006;20:76-79.

3 Bhandari M, Guyatt GH, Swiontkowski MF, et al. A lack of consensus in the assessment of fracture healing among orthopaedic surgeons. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16:562-566.

4 Sarmiento A. On the behavior of closed tibial fractures: Clinical/radiological correlations. J Orthop Trauma. 2000;14:199-205.

5 Greenwood DC, Muir KR, Doherty M, et al. Conservatively managed tibial shaft fractures in Nottingham, UK: Are pain, osteoarthritis, and disability long-term complications? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1997;51:701-704.

6 Obremskey WT, Medina M. Comparison of intramedullary nailing of distal third tibial shaft fractures: Before and after traumatologists. Orthopedics. 2004;27:1180-1184.

7 Bhandari M, Devereaux PJ, Li P, et al. Misuse of baseline comparison tests and subgroup analyses in surgical trials. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 2006;447:247-251.

8 Kristensen KD, Kiaer T, Blicher J. No arthrosis of the ankle 20 years after malaligned tibial-shaft fracture. Acta Orthop Scand. 1989;60:208-209.

9 Kettelkamp DB, Hillberry BM, Murrish DE, Heck DA. Degenerative arthritis of the knee secondary to fracture malunion. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1988;234:159-169.

10 Merchant TC, Dietz FR. Long-term follow-up after fractures of the tibial and fibular shafts. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:599-606.

11 Cedell CA. Supination-outward rotation injuries of the ankle. A clinical and roentgenological study with special reference to the operative treatment. Acta Orthop Scand.; suppl 110; 1967; 3.

12 Magnusson R. On the late results in non-operated cases of malleolar fractures. clinical-roentgenological-statistical study: fractures by external rotation. Acta Chirugica Scandinavica. 1944;1:1-36.

13 Netz P, Olsson E, Ringertz H, Stark A. Functional restitution after lower leg fractures. A long-term follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1991;110:238-241.

14 Milner SA, Davis TRC, Muir KR, et al. Long-term outcome after tibial shaft fracture: Is malunion important? J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:971-980.

15 van der Schoot DK, Den Outer AJ, Bode PJ, et al. Degenerative changes at the knee and ankle related to malunion of tibial fractures. 15-year follow-up of 88 patients. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78:722-725.

16 Puno RM, Vaughan JJ, Stetten ML, Johnson JR. Long-term effects of tibial angular malunion on the knee and ankle joints. J Orthop Trauma. 1991;5:247-254.

17 Kyro A. Malunion after intramedullary nailing of tibial shaft fractures. Ann Chir Gynaecol. 1997;86:56-64.

18 Bhandari M, Tornetta PIII, Ellis T, et al. Hierarchy of evidence: Differences in results between non-randomized studies and randomized trials in patients with femoral neck fractures. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 2004;124:10-16.

19 Boucher M, Leone J, Pierrynowski M. Three-dimensional assessment of tibial malunion after intramedullary nailing: a preliminary study. J Orthop Trauma. 2002;16(7):473-483.