Chapter 32 What Is the Optimal Treatment for Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis?

Slipped capital femoral epiphysis (SCFE) is an adolescent hip disorder in which there is a displacement of the capital femoral epiphysis from the metaphysis through the physis. Most cases are “idiopathic,” although they may also occur from a known endocrine disorder,1–3 renal failure osteodystrophy,4 or previous radiation therapy.3,5, 6 This chapter is limited to the idiopathic SCFE. SCFEs are classified both by their clinical nature and magnitude. The traditional clini-cal classification was acute, chronic, and acute on chronic,7–11 and it was based on the patient’s history, physical examination, and roentgenograms. An acute SCFE case is defined as those with symptoms for less than 3 weeks with an abrupt displacement through the proximal physis in which there was a preexisting epiphyseolysis.7 Chronic SCFE cases account for 85% of all slips12 and present with more than 3 weeks of groin, thigh, and knee pain, often for months to years. These patients often have a history of exacerbations and remissions of the pain and limp. Acute-on-chronic SCFEs are those with chronic symptoms initially and the subsequent development of acute symptoms. A newer, more clinically useful classification is dependent on physeal stability, which imparts a prognosis to the hip regarding subsequent avascular necrosis (AVN).13 A stable SCFE is defined as one where the child is able to ambulate, with or without crutches. An unstable SCFE is defined as one where the child cannot ambulate, with or without crutches. Unstable SCFE cases have a much greater incidence rate of AVN, up to 50% in some series, compared with stable SCFEs (nearly 0%).13

OPTIONS

Once a diagnosis of SCFE is made, treatment is indicated to prevent slip progression14–16 and to avoid complications, especially AVN and chondrolysis. Multiple treatment options are available, each having specific advantages and disadvantages. These options are divided into those for patients with stable SCFE and those for patients with unstable SCFE.

Treatment options for a stable SCFE include: (1) in situ stabilization with a single screw8,9,17-21 or multiple pins17,22–25; (2) epiphyseodesis25–30; (3) open reduction with corrective osteotomy through the physis and internal fixation18,22,30–39; (4) basilar neck osteotomy40–42; (5) intertrochanteric osteotomy24,42-46; and (6) surgical dislocation of the hip with transphyseal callus removal, reduction, and fixation.47–51

LEVELS OF EVIDENCE

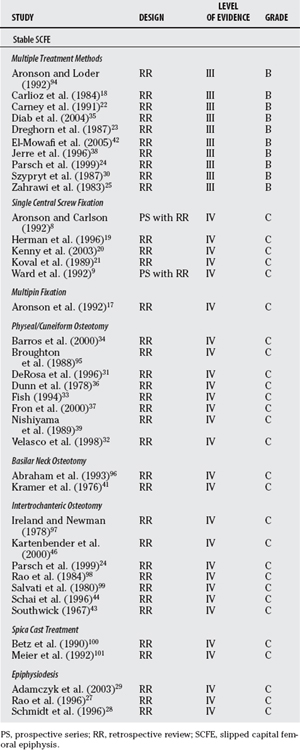

The treatment of SCFE has been one of gradual evolution over time. The available studies (Table 32-1) are, at best, Level III; no randomized, controlled studies and few prospective comparative studies involve SCFE. For this reason, I review the few Level III and the most appropriate Level IV series, compare and contrast them regarding long-term outcomes and complications, synthesize the data, and propose as best as possible the optimal treatment of SCFE.

As a background to considering the various different treatments for SCFE, it is first necessary to understand the long-term natural history of the untreated SCFE and the long-term outcomes from SCFEs treated many years ago. The two major concerns in the untreated individual with SCFE are the risk for further progression and the risk for degenerative joint disease in adult life. Few long-term studies of patients with SCFE and even fewer untreated individual are included in these series.11,22,52–56 Ordeberg and researchers57 studied a series of patients with SCFE without primary treatment 20 to 40 years after diagnosis. Few patients had restrictions in working capacity or social life. However, there was a risk for slip progression as long as the physis remained open.58 Carney and coauthors22 reported on 35 patients with SCFE who were initially observed; in 6 hips (17%), gradual progression occurred, with 5 becoming severe. An additional 11 patients had an acute episode superimposed on the chronic SCFE; all progressed to severe displacement and required surgical stabilization.

Howorth59 (Level V evidence) states that SCFE is likely the most frequent cause of degenerative joint disease of the hip in middle life, and a common source of pain and disability. This is not necessarily supported by other studies. The number of patients with known SCFE is low (average 5%) in reviewing large series of patients with degenerative joint disease.60–62 The severity of deformity in the untreated SCFE is known to correlate with the long-term prognosis regarding degenerative joint disease.22,52, 54, 56, 63, 64 Oram54 reports on 22 patients with untreated SCFEs; patients with moderate SCFEs retained good function for years, whereas patients with severe SCFEs experienced development of degenerative joint disease within 15 years. Jerre63,64 and Ross and colleagues56 report increasingly poor results with longer follow-up periods; many patients responded well early on but experienced development of increasing symptoms and decreasing function with increasing age. Carney and Weinstein52 studied the natural history of the untreated, chronic SCFE in 31 hips at an average follow-up period of 41 years. The average Iowa Hip Rating was 92 in the 17 patients with mild SCFE, 87 in the 11 patients with moderate SCFE, and 75 in the 3 patients with severe SCFE. Although a patient with a mild SCFE appears to have a favorable prognosis, patients with moderate and severe SCFE have a high incidence of degenerative joint disease. Poor results, however, can occasionally be seen even with minimal SCFEs.11,22, 52, 56 In summary, the natural history of chronic (stable) SCFE is favorable provided that displacement is mild and remains so. Thus, all treatments should stabilize the SCFE and prevent complications.

What are the long-term historical results of treatment? Wilson and coworkers65 reviewed 300 hips treated between 1936 and 1960. Good results were seen in 81% of those treated with in situ fixation and in 60% of those with deformity correction. Hall53 reviewed 138 patients; excellent results were seen in 80% of those treated with multiple pin fixation; realignment with osteotomy of the femoral neck resulted in a 38% AVN rate with 36% poor results. Ordeberg and researchers66 reviewed 44 patients with untreated SCFE followed for more than 30 years. Symptomatic treatment or fixation in situ gave excellent results, with only 2% needing a secondary reconstructive procedure. Closed reduction or spica cast treatment had a combined rate of AVN and chondrolysis of 13%, with 35% needing a reconstructive procedure; femoral neck osteotomy resulted in a combined rate of AVN and chondrolysis of 30%, with 15% needing a reconstructive procedure.57 Carney and coauthors22 report on 155 hips at a mean follow-up of 41 years. Poorer results were associated with more severe slips and realignment; chondrolysis (16%) and AVN (12%) were more common with increasing slip severity. All these long-term studies support the use of in situ fixation as the treatment of choice for SCFE regardless of slip severity. Realignment was associated with significant complications and poorer results. It must be remembered, however, that the surgical fixation techniques and imaging modalities used in these historical series are much different from those currently used.

Stable Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

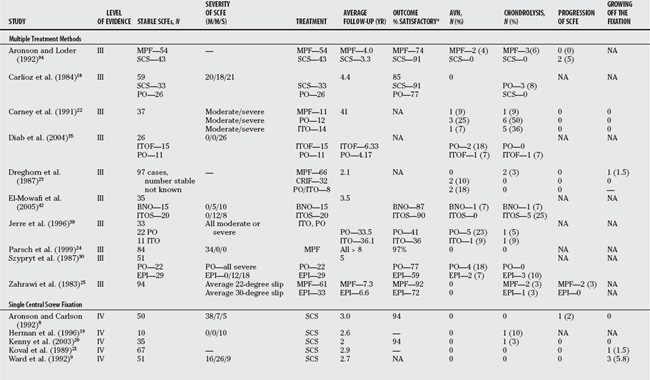

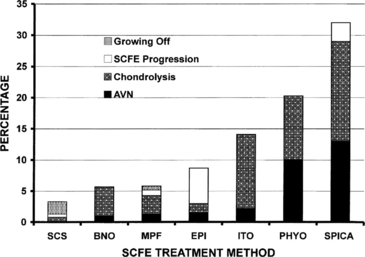

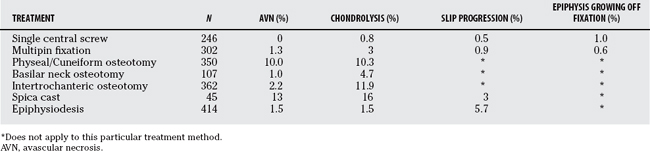

The incidence rates of AVN range from 0% to 10%, of chondrolysis from 0.8% to 16%, and slip progression from 0.5% to 5.7% (Tables 32-2, 32-3, and 32-4). The lowest rates of AVN, chondrolysis, and slip progression in aggregate are those treated with a single central screw (see Table 32-4). The advantages of single-screw fixation for a patient with a stable SCFE include a high success rate, a low incidence rate of further slippage, and a low incidence rate of complications.8,67, 68

TABLE 32-3 Compiled Results of Outcomes for Different Methods of Treatment in Stable Idiopathic Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

TABLE 32-4 Summary of Literature Results in the Treatment of Stable, Idiopathic Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

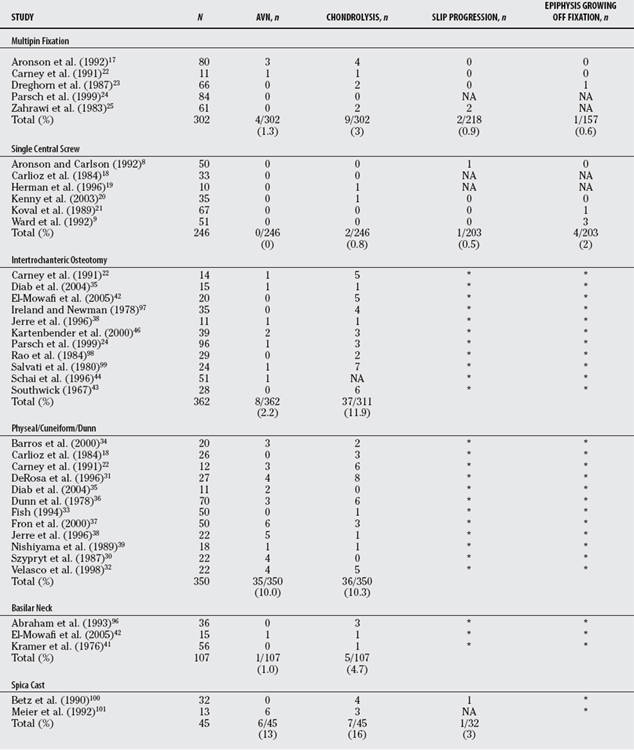

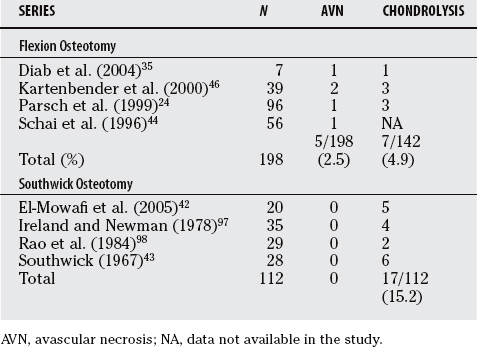

Osteotomies are used in an attempt to correct the deformity associated with SCFE. The overall incidence rate of both chondrolysis and AVN in 350 cases of physeal/cuneiform osteotomy compiled from the literature was 10%. Because of this high risk for AVN and subsequent poor results in most series, a physeal cuneiform osteotomy is not recommended in the treatment of SCFE. A compensating base-of-neck osteotomy is an attempt to maintain the advantages of a physeal osteotomy (deformity correction) but with a lower risk for AVN. Indeed, the incidence rate of AVN is less with basilar neck osteotomies compared with the cuneiform osteotomy (10% vs. 1%). The intertrochanteric osteotomy is an attempt to improve hip motion, obtain some correction of the deformity (albeit a compensatory correction), and completely avoid AVN. The compiled results demonstrate that AVN still occurs with a 2.2% incidence rate and also carries a significant risk for chondrolysis (11.9%). The results of intertrochanteric osteotomy using the Southwick technique are much poorer than those of in situ single-screw fixation.43,44, 69 The simpler Imhäuser flexion intertrochanteric osteotomy24,45, 46 has replaced the Southwick osteotomy. Because it is not a valgus, limb-lengthening osteotomy, the increase in joint pressure created by the traditional Southwick osteotomy, a likely cause of chondrolysis, is avoided. When comparing the results (Table 32-5) between the flexion and Southwick types of osteotomies, the rate of AVN and chondrolysis is 2.5% (5/198) and 4.9% (7/142) for the flexion osteotomy and 0% (0/112) and 15.2% (17/112) for the Southwick osteotomy. Although the rate of chondrolysis is lower for the flexion osteotomy, there is an increase in the rate of AVN with the flexion osteotomy.

TABLE 32-5 Comparisons between the Flexion and Southwick Types of Intertrochanteric Osteotomies in the Treatment of Stable, Idiopathic Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

In conclusion, when reviewing all the evidence and published series to date, it is clear that the optimal treatment for the stable, idiopathic SCFE is single central screw fixation (Figs. 32-1 and 32-2).

Unstable Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

The treatment for the unstable SCFE is controversial as shown by survey studies of both North American70 and European71 pediatric orthopedic surgeons. An urgent/emergent treatment was favored by 88% of North American and European surgeons; a manipulative reduction was favored by 32% of European and 12% of North American surgeons, whereas more North American surgeons (84%) favored an incidental reduction. Single-screw fixation was recommended by 57% of North American surgeons and 79% of European surgeons, with double-screw fixation being recommended by 40% of North American and only 18% of European surgeons. Capsular decompression was recommended by 29% of the European and 35% of the North American surgeons. This Level V evidence clearly indicates that the best treatment for an unstable SCFE is not yet known.

In the initial study that described the unstable SCFE, the risk for AVN was 47%.13 It was 88% in those when operative stabilization occurred less than 48 hours after the onset of symptoms versus 32% in those more than 48 hours. However, the cause-and-effect relation between the timing of operative stabilization and the development of AVN could not be determined.

Several authors have attempted to answer these questions (Table 32-6). Some72–74 believe that reduction reduces the incidence of AVN, others75,76 believe that reduction has no influence on the development of AVN, and a few77 believe that reduction increases the incidence of AVN. Peterson and colleagues,73 in 91 patients with unstable SCFEs at an average follow-up period of 44 months, note that the incidence rate of AVN was 7% when a closed reduction was performed less than 24 hours from presentation and 20% when performed more than 24 hours from presentation. The authors believe that the acute displacement of the femoral epiphysis compromises the blood flow, which may be restored by a timely reduction of the SCFE. Gordon and coworkers72 support this concept, with no cases of AVN in 10 patients with unstable SCFE treated within 24 hours by reduction, arthrotomy, and double-screw fixation. Maeda and researchers,78 using angiography, demonstrated restoration of blood supply to the epiphysis after reduction of an unstable SCFE. Phillips and coauthors74 reviewed 14 patients with unstable SCFE, and noted no complication in those who were treated with early reduction and stabilization. By contrast, Tokmakova and coworkers77 reviewed 36 patients with unstable SCFEs and noted a 58% AVN incidence rate. Their multiple logistic regression analysis showed that a complete or partial reduction of an unstable SCFE increased the chances of AVN; they thus recommend in situ fixation with a single central screw as the treatment for the unstable SCFE. Kalogrianitis and investigators79 recommend that the reduction be performed within 24 hours, and that after that the epiphysis is much more susceptible to AVN and thus to defer definitive treatment until at least 1 week has passed.

TABLE 32-6 Treatment Outcomes for Prophylactic Fixation of the Opposite Hip in Children with Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Several studies address the number of screws that should be used in the patient with unstable SCFE, but nearly all are in vitro animal models and different than the clinical situation. Karol and researchers80 and Kibiloski and colleagues81 compared single- and double-screw fixation in a calf model, testing in both a single load to failure and the effects of physiologic shear loading. Double-screw fixation did not double the strength compared with single-screw fixation for either a single load to failure or simulated walking. Both articles recommend protected weight bearing in the postoperative period for the unstable SCFE regardless of whether 1 or 2 screws are used. Again, in an immature bovine model, Kishan and coworkers82 evaluated one and two screws in varying degrees of configuration at physiologically relevant loads, and they found no significant differences among three different screw configurations, but that double-screw constructs were 66% stiffer and 66% stronger than single-screw constructs. In an immature porcine model, Snyder and coauthors83 studied torsional strength after removal of the perichondrium at the physeal level (analogous to the situation, the unstable SCFE where the perichondrium at the physeal level has been compromised). Two-screw fixation after removal of the perichondrium provided 43% of the stiffness and 74% of the strength of the intact physis in torsion.

Prophylactic Treatment of the Opposite Hip

The risk for a contralateral SCFE developing in a patient with unilateral SCFE is reported to be 2335 times greater than the risk for an initial SCFE,84 yet even if the bilaterality incidence rate is 60%, then 40% of children with SCFE will have unnecessary surgery if prophylactic fixation is performed on all children with idiopathic SCFE. Prophylactic fixation is recommended by some researchers,85–87 whereas close observation is recommended by others.88,89 Therefore, what is the level of evidence regarding prophylactic fixation?

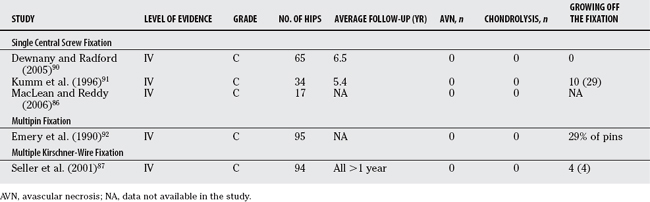

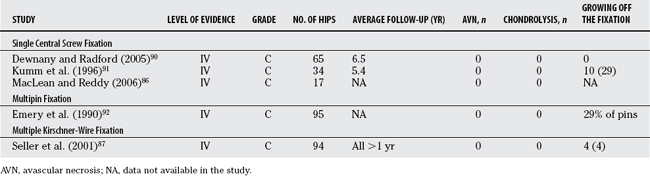

First, is prophylactic fixation safe? Few series report the results of prophylactic fixation86,87,90–92 (Table 32-7). The combined number of hips treated prophylactically in these 5 studies is 305. No AVN or chondrolysis was found, although in some cases, the epiphysis grew off the fixation (7.3% in the 3 series in which it was recorded accurately87,90, 91). Thus, it seems relatively clear that with today’s methods of single central screw fixation, prophylactic fixation can be performed with a low incidence of complications.

TABLE 32-7 Treatment Outcomes for Prophylactic Fixation of the Opposite Hip in Children with Slipped Capital Femoral Epiphysis

Considering this relative safety, it then becomes necessary to determine when prophylactic fixation should be performed in child with a unilateral stable, idiopathic SCFE. A POSNA membership survey (Level V evidence) recommends prophylactic fixation of the opposite hip70 in only 12.2% of cases. Two recent studies using decision analysis models have been performed to assist in this dilemma, but they have come to differing conclusions. Schultz and investigators84 developed a model with probabilities for the occurrence of a contralateral SCFE. They conclude that prophylactic fixation of the contralateral hip was beneficial to the long-term outcome of the hip, but cautioned that the clinician use sound clinical judgment with respect to the age, sex, and endocrine status of the patient, including the preferences of the patient and family, before recommending prophylactic fixation of the contralateral hip. Kocher and coworkers93 similarly used a decision analysis model with probabilities for the occurrence of a contralateral SCFE and reached the conclusion that when the probability of a contralateral SCFE is greater than 27% or in cases where reliable follow-up is not feasible, then prophylactic fixation of the contralateral hip is favored. The difference between these studies is how the probabilities of a contralateral SCFE were determined. Schultz and investigators84 used values from the literature for various incidences and probabilities of events (e.g., AVN, chondrolysis, severity of SCFE, etc.). Kocher and coworkers93 used a questionnaire to determine patient preferences in a group of children without SCFE; the questionnaire posed scenarios for different outcomes and asked the patients to rate pre-ferences regarding prophylactic fixation in that framework. Unfortunately, these decision analysis models have not yet answered this controversial question: What are the exact indications for prophylactic treatment? Table 32-8 provides a summary of recommendations for the treatment of SCFE.

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

|---|---|---|

1 Loder RT, Wittenberg B, DeSilva G. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis associated with endocrine disorders. J Pediatr Orthop. 1995;15:349-356.

2 Wells D, King JD, Roe TF, et al. Review of slipped capital femoral epiphysis associated with endocrine disease. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:610-614.

3 McAffee PC, Cady RB. Endocrinologic and metabolic factors in atypical presentations of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Report of four cases and review of the literature. Clin Orthop. 1983;180:188-196.

4 Loder RT, Hensinger RN. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis associated with renal failure osteodystrophy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:205-211.

5 Loder RT, Hensinger RN, Alburger PD, et al. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis associated with radiation therapy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1998;18:630-636.

6 Liu S-C, Tsai C-C, Huang C-H. Atypical slipped capital femoral epiphysis after radiotherapy and chemotherapy. Clin Orthop. 2004;426:212-218.

7 Fahey JJ, O’Brien ET. Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47-A:1105-1127.

8 Aronson DD, Carlson WE. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: A prospective study of fixation with a single screw. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74-A:810-819.

9 Ward WT, Stefko J, Wood KB, et al. Fixation with a single screw for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74-A:799-809.

10 Aadalen RJ, Weiner DS, Hoyt W, et al. Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56-A:1473-1487.

11 Boyer DW, Mickelson MR, Ponseti IV. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Long-term follow-up of one hundred and twenty-one patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1981;63-A:85-95.

12 Loder RT, Aronson DD, Greenfield ML. The epidemiology of bilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. A study of children in Michigan. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75-A:1141-1147.

13 Loder RT, Richards BS, Shapiro PS, et al. Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis: The importance of physeal stability. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1993;75-A:1134-1140.

14 Kocher MS, Bishop JA, Weed B, et al. Delay in diagnosis of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Pediatrics. 2004;113:e322-e325.

15 Loder RT, Starnes T, Dikos G, et al. Demographic predictors of severity of stable slipped capital femoral epiphyses. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2006;88-A:97-105.

16 Rahme D, Comley A, Foster B, et al. Consequences of diagnostic delays in slipped capital femoral epiphyhsis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2006;15:93-97.

17 Aronson DD, Peterson DA, Miller DV. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: The case for internal fixation in situ. Clin Orthop. 1992;281:115-122.

18 Carlioz H, Vogt JC, Barba L, et al. Treatment of slipped upper femoral epiphysis: 80 cases operated on over 10 years (1968–1978). J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4:153-161.

19 Herman MJ, Dormans JP, Davidson RS, et al. Screw fixation of grade III slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1996;322:77-85.

20 Kenny P, Higgisn T, Sedhom M, et al. Slipped upper femoral epiphysis. A retrospective, clinical and radiological study of fixation with a single screw. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2003;12:97-99.

21 Koval KJ, Lehman WB, Rose D, et al. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a cannulated-screw technique. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71-A:1370-1377.

22 Carney BT, Weinstein SW, Noble J. Long-term follow-up of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1991;73-A:667-674.

23 Dreghorn CR, Knight D, Mainds CC, et al. Slipped upper femoral epiphysis-a review of 12 years of experience in Glasgow (1972–1983). J Pediatr Orthop. 1987;7:283-287.

24 Parsch K, Bühl T, Weller S. Intertrochanteric corrective osteotomy for moderate and severe chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1999;8:223-230.

25 Zahrawi FB, Stephens TL, Spencer GEJr, et al. Comparitive study of pinning in situ and open epiphysiodesis in 105 patients with slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1983;177:160-168.

26 Weiner DS, Weiner S, Melby A, et al. A 30-year experience with bone graft epiphysiodesis in the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1984;4:145-152.

27 Rao SB, Crawford AH, Burger RR, et al. Open bone peg epiphysiodesis for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:37-48.

28 Schmidt TL, Cimino WG, Seidel FG. Allograft epiphysiodesis for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1996;322:61-76.

29 Adamczyk MJ, Weiner DS, Hawk D. A 50-year experience with bone graft epiphysiodesis in the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2003;23:578-583.

30 Szypryt EP, Clement DA, Colton CL. Open reduction or epiphysiodesis for slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1987;69-B:737-742.

31 DeRosa GP, Mullins RC, Kling TFJr. Cuneiform osteotomy of the femoral neck in severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1996;322:48-60.

32 Velasco R, Schai PA, Exner GU. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: A long-term follow-up study after open reduction of the femoral head combined with subcapital wedge resection. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1998;7:43-52.

33 Fish JB. Cuneiform osteotomy of the femoral neck in the treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1994;76-A:46-59.

34 Barros JW, Tukiama G, Fontoura C, et al. Trapezoid osteotomy for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Int Orthop. 2000;24:83-87.

35 Diab M, Hresko MT, Millis MB. Intertrochanteric versus subcapital osteotomy in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 2004;427:204-212.

36 Dunn DM, Angel JC. Replacement of the femoral head by open operation in severe adolescent slipping of the upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60-B:394-403.

37 Fron D, Forgues D, Mayrargue E, et al. Follow-up study of severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis treated with Dunn’s osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:320-325.

38 Jerre R, Billing L, Karlsson J. Long-term results after realignment operations for slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1996;78-B:745-750.

39 Nishiyama K, Sakamaki T, Ishii Y. Follow-up of the subcapital wedge osteotomy for severe chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1989;9:412-416.

40 Barmada R, Bruch RF, Gimbel JS, et al. Base of the neck extracapsular osteotomy for correction of deformity in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1978;132:98-101.

41 Kramer WG, Craig WA, Noel S. Compensating osteotomy at the base of the femoral neck for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1976;58-A:796-800.

42 El-Mowafi H, El-Adl G, El-Lakkany MR. Extracapsular base of neck osteotomy versus Southwick oseotomy in treatment of moderate to severe chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:171-177.

43 Southwick WO. Osteotomy through the lesser trochanter for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1967;49-A:807-835.

44 Schai PA, Exner GU, Hansch O. Prevention of secondary coxarthrosis in slipped capital femoral epiphysis: A long-term follow-up study after corrective intertrochanteric osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5:135-143.

45 Kamegaya M, Saisu T, Ochiai N, et al. Preopertive assessment for intertrochanteric femoral osteotomies in severe chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis using computed tomography. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:71-78.

46 Kartenbender K, Cordier W, Katthagen B-D. Long-term follow-up study after corrective Imhäuser osteotomy for severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:749-756.

47 Leunig M, Casillas MM, Hamlet M, et al. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Early mechanical damage to the acetabular cartilage by a prominent femoral metaphysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 2000;71:370-375.

48 Ganz R, Gill TJ, Gautier E, et al. Surgical dislocation of the adult hip. A technique with full access to the femoral head and acetabulum without the risk of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83-B:1119-1124.

49 Spencer S, Millis MB, Kim Y-J. Early results of treatment for hip impingement syndrome in slipped capital femoral epiphysis and pistol grip deformity of the femoral head-neck junction using the surgical dislocation technique. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:281-285.

50 Beck M, Leunig M, Parvizi J, et al. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement. Part II. Midterm results of surgical treatment. Clin Orthop. 2004;418:67-73.

51 Lavigne M, Parvizi J, Beck M, et al. Anterior femoroacetabular impingement. Part 1. Techniques of joint preserving surgery. Clin Orthop. 2004;418:61-66.

52 Carney BT, Weinstein SL. Natural history of untreated chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1996;322:43-47.

53 Hall JE. The results of treatment of slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1957;39-B:659-673.

54 Oram V. Epiphysiolysis of the head of the femur. A follow-up examination with special reference to end results and the social prognosis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1953;23:100-120.

55 Ponseti I, Barta CK. Evaluation of treatment of slipping of the capital femoral epiphysis. Surg Gynecol Obstet. 1948;86:87-97.

56 Ross PM, Lyne ED, Morawa LG. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Long term results after 10–38 years. Clin Orthop. 1979;141:176-180.

57 Ordeberg G, Hansson LI, Sandström S. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis in southern Sweden. Clin Orthop. 1987;220:148-154.

58 Jerre R, Hansson G, Wallin J, et al. Does a single device prevent further slipping of the epiphysis in children with slipped capital femoral epiphysis? Arch Orthop Trauma Surg. 1997;116:348-351.

59 Howorth B. History. Slipping of the capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1966;48:12-32.

60 Johnston RC, Larson CB. Results of treatment of hip disorders with cup arthroplasty. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1969;51-A:1461.

61 Murray RO. The etiology of primary osteoarthritis of the hip. Br J Radiol. 1965;38:810-824.

62 Solomon L. Patterns of osteoarthritis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1976;58-B:176-183.

63 Jerre T. A study in slipped upper femoral epiphysis with special reference to late functional and reontgenological results and the value of closed reduction. Acta Orthop Scand. 6(suppl), 1950.

64 Jerre T. Early complications of osteosynthesis with a three flanged nail in situ for slipped epiphysis. Acta Orthop Scand. 1958;27:126.

65 Wilson PD, Jacobs B, Schecter L. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis. An end-result study. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1965;47-A:1128-1145.

66 Ordeberg G, Hansson LI, Sandström S. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis in southern Sweden. Long-term results with no treatment or symptomatic primary treatment. Clin Orthop Relat Res.; 191; 1984; 95-104.

67 Goodman WW, Johnson JT, Robertson WWJr. Single screw fixation for acute and acute-on-chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Clin Orthop. 1996;322:86-90.

68 Stevens DB, Short BA, Burch JM. In situ fixation of the slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a single screw. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5:85-89.

69 Southwick WO. Compression fixation after biplane intertrochanteric osteotomy for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1973;55-A:1218-1224.

70 Mooney JFIII, Sanders JO, Browne RH, et al. Management of unstable/acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Results of a survey of the POSNA membership. J Pediatr Orthop. 2005;25:162-166.

71 Witbreuk M, Besselaar P, Eastwood D. Current practice in the management of the acute/unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis in the United Kingdom and the Netherlands: Results of a survey of the membership of the British Society of Children’s Orthopaedic Surgery and the Wekrgroep Kinder Orthopaedie. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2007;16:79-83.

72 Gordon JE, Abrahams MS, Dobbs MB, et al. Early reduction, arthrotomy, and cannulated screw fixation in unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis treatment. J Pediatr Orthop. 2002;22:352-358.

73 Peterson MD, Weiner DS, Green NE, et al. Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis: The value and safety of urgent manipulative reduction. J Pediatr Orthop. 1997;17:648-654.

74 Phillips SA, Griffiths WEG, Clarke NMP. The timing and reduction and stabilisation of the acute, unstable slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2001;83-B:1046-1049.

75 Fallath S, Letts M. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis: An analysis of treatment outcome according to physeal stability. Can J Surg. 2004;47:284-289.

76 Rattey T, Piehl F, Wright JG. Acute slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Review of outcomes and rates of avascular necrosis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1996;78-A:398-402.

77 Tokmakova KP, Stanton RP, Mason DE. Factors influencing the development of osteonecrosis in patients treated for slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2003;85-A:798-801.

78 Maeda S, Kita A, Funayama K, et al. Vascular supply to slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2001;21:664-667.

79 Kalogrianitis S, Tan CK, Kemp GJ, et al. Does unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis require urgent stabilization? J Pediatr Orthop B. 2007;16:6-9.

80 Karol LA, Doane RM, Cornicelli SF, et al. Single versus double screw fixation for treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis: A biomechanical analysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:741-745.

81 Kibiloski LJ, Doane RM, Karol LA, et al. Biomechanical analysis of single- versus double-screw fixation in slipped capital femoral epiphysis at physiological load levels. J Pediatr Orthop. 1994;14:627-630.

82 Kishan S, Upasani V, Mahar A, et al. Biomechanical stability of single-screw versus two-screw fixation of an unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis model: Effect of screw position in the femoral neck. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:601-605.

83 Snyder RR, Williams JL, Schmidt TL, et al. Torsional strength of double- versus single-screw fixation in a pig model of unstable slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2006;26:295-299.

84 Schultz WR, Weinstein JN, Weinstein SL, et al. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Evaluation of long-term outcome for the contralateral hip with use of decision analysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84-A:1305-1314.

85 Hägglund G. The contralateral hip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 1996;5:158-161.

86 MacLean JGB, Reddy SK. The contralateral slip. An avoidable complication and indication for prophylactic pinning in slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2006;88-B:1497-1501.

87 Seller K, Raab P, Wild A, et al. Risk-benefit analysis of prophylactic pinning in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop B. 2001;10-B:192-196.

88 Castro FPJr., Bennett JT, Doulens K. Epidemiological perspective on prophylactic pinning in patients with unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 2000;20:745-748.

89 Jerre R, Billing L, Hansson G, et al. The contralateral hip in patients primarily treated for unilateral slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1994;76-B:563-567.

90 Dewnany G, Radford P. Prophylactic contralateral fixation in slipped upper epiphysis: Is it safe? J Pediatr Orthop B. 2005;14:429-433.

91 Kumm DA, Schmidt J, Eisenburger S-H, et al. Prophylactic dynamic screw fixation of the asymptomatic hip in slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Pediatr Orthop. 1996;16:249-253.

92 Emery RJH, Todd RC, Dunn DM. Prophylactic pinning slipped upper femoral epiphysis. Prevention of complications. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1990;72-B:217-219.

93 Kocher MS, Bishop JA, Hresko MT, et al. Prophylactic pinning of the contralateral hip after unilateral slipped capital femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2004;86-A:2658-2665.

94 Aronson DD, Loder RT. Slipped capital femoral epiphysis in Black children. J Pediatr Orthop. 1992;12:74-79.

95 Broughton NS, Todd RC, Dunn DM, et al. Open reduction of the severely slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1988;70-B:435-439.

96 Abraham E, Garst J, Barmada R. Treatment of moderate to severe slipped capital femoral epiphysis with extracapsular base of neck osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop. 1993;13:294-302.

97 Ireland J, Newman PH. Triplane osteotomy for severely slipped upper femoral epiphysis. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1978;60-B:390-393.

98 Rao JP, Francis AM, Siwek CW. The treatment of chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis by biplane osteotomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1984;66-A:1169-1175.

99 Salvati EA, Robinson HJJr, O’Dowd TJ. Southwick osteotomy for severe chronic slipped capital femoral epiphysis: Results and complications. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1980;62-A:561-570.

100 Betz RR, Steel HH, Emper WD, et al. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis. Spica cast immobilization. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72-A:587-600.

101 Meier MC, Meyer LC, Ferguson RL. Treatment of slipped capital femoral epiphysis with a spica cast. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1992;74-A:1522-1529.