Chapter 8 What Is the Optimal Method of Managing a Patient with Cervical Myelopathy?

Cervical spondylotic myelopathy (CSM) is the most common cause of spinal cord dysfunction in the elderly and the most common cause of nontraumatic spastic paraparesis and quadriparesis.1 Although CSM is a common disorder, the treatment of CSM remains controversial in terms of “surgery or conservative management,” “surgical indication and timing of surgery,” “surgical approach,” and “type of surgery.” This chapter reviews and discusses evidence-based literature on the optimal management of CSM.

SURGERY VERSUS CONSERVATIVE MANAGEMENT: TIMING OF SURGERY

Knowledge of the natural history of CSM is critical in decision making for treatment of CSM. However, few studies and no Level I evidence studies are available. Early studies on the course of CSM suggest that most patients with myelopathy experience progressive neurological worsening, most commonly with episodic deterioration.2–4 In contrast, another long-term study of myelopathic patients by Lees and Turner5 shows that a long period of nonprogression was the rule and progressive deterioration was the exception. A small cohort study of 24 patients, treated by collar immobilization and followed for a mean duration of 6.5 years, found that the conditions of approximately one third of patients improved, one third deteriorated, and one third were stable.6 Similar results were confirmed by Nurick.7 In the majority of CSM cases, there is an initial phase of deterioration, followed by a stable period lasting a number of years, during which the degree of disability does not change significantly for those mildly affected. In general, older patients and those with motor deficits are more likely to experience development of progressive deterioration. As a result, Nurick7 states that surgery should be reserved for those with progressive disability and those older than 60 years. Patients with milder disease may have a better prognosis.8 However, some authors state that patients treated conservatively show progressive neurologic deterioration.9,10 In addition, patients with CSM may be at increased risk for spinal cord injury after minor trauma,11 which supports early intervention for even mildly symptomatic patients. Few direct comparisons of conservative and operative treatment in patients with myelopathy exist even in the recent literature. A nonrandomized cohort study comparing medical and surgical treatment in 43 patients, 23 of whom were treated without surgery, reported significant worsening of their ability to perform activities of daily living, with worsening of neurologic symptoms.12 In contrast, 20 surgically treated patients had a significant improvement in functional status and overall pain with improvement also observed in neurologic symptoms. Although this study demonstrates that the results of surgical treatment are better than those of conservative management, it lacks randomization and had significant treatment selection bias. In the 2002 Cochrane review on the role of surgery for cervical myelopathy,13 one small study reports 49 patients with mild or moderate myelopathy who were randomized to surgery versus conservative treatment. Although age and sex ratios were similar between the two groups, the conservative group had slightly better modified Japanese Orthopaedic Association (mJOA) scores, suggesting a possible bias in treatment allocation. At 6 months, mJOA scores and gait scores were better in the conservatively treated group. But no differences were reported at 2 years. In addition, a subgroup with severe disability improved after surgical intervention.13 A more recent 3-year, prospective, randomized study of 68 patients with mild-to-moderate nonprogressive CSM did not demonstrate a significant difference in outcomes (mJOA score and self-evaluation) between surgically and nonsurgically treated patients.14 In addition, timed 10-m walk in the nonsurgical group was significantly better than that in the surgical group. The authors conclude that their results could mean that the conservative approach can treat CSM with a degree of success similar to that of surgery for at least 3 years, supporting rather than proving the “wait and see” strategy.14 This study failed to prove that surgical intervention has any advantage over conservative management. However, the poor specificity of the mJOA scoring scale, the small number of randomized patients, and relatively short follow-up period for this disorder (3 years) may account for the apparent lack of any lasting beneficial effect of surgery on the natural history of cervical myelopathy. In addition, the potential risk for spinal cord injury after minor trauma, which is impossible to quantify, should be considered when conservative management is selected.

Kadanka and colleagues’15 more recent study of a subclass analysis demonstrated that the patients with a good outcome in the surgically treated group had a more serious clinical picture (expressed in mJOA score and slower walk). They conclude that surgery is more suitable for patients who are clinically worse and have a spinal canal transverse area of less than 70 mm2.15 Once moderate signs and symptoms develop, patients are less likely to improve on their own and would likely benefit from surgical intervention.16

One crucial question is what group of patients will experience development of CSM and clinically pro-gress. Bednarik and investigators17 conducted a prospective cohort study of clinically asymptomatic cervical cord compression cases (66 cases). Patients were managed to determine which patients experienced development of clinical signs of cervical myelopathy. During a median 4-year follow-up period, clinical signs of myelopathy were detected in 13 patients (19.7%). These signs were also associated with symptomatic cervical radiculopathy, electromyographic evidence of an anterior horn lesion, and abnormal somatosensory-evoked potentials.

Little information is available on nonoperative treatment of cervical myelopathy. Cervical collars have been recommended for symptomatic relief but have no effect on long-term outcomes, including neurologic progression. Although a recent study demonstrated the effectiveness of “rigorous” conservative management including 3- or 4-hour cervical traction, cervical orthosis, drug therapy, and exercise therapy,18 manipulation and traction are generally considered to be contraindicated because of the potential for aggravation of neurologic symptoms.2

SELECTION OF THE SURGICAL APPROACH

Selection of the appropriate surgical approach is based on a complete understanding of the factors responsible for the cord dysfunction. Because abnormal radiographic findings are common even in asymptomatic patients,17,19 clinicians need to be careful to correlate the patient’s complaints, physical examination, and imaging results to discern the precise diagnosis. The purpose of surgery is to decompress neural elements, restore lordosis, and stabilize the spine to prevent additional degeneration at the affected level. Surgery for CSM has been performed by anterior, posterior, and combined approaches; each has unique advantages and disadvantages. The decision of which surgical approach to use is based on multiple factors, including the source of spinal cord compression, the number of vertebral segments involved in the disease process, cervical alignment, the magnitude of coexisting neck pain, patient comorbidities, and the surgeon’s familiarity with various techniques. Therefore, the selection of surgical approach remains controversial, especially in patients with multilevel degenerative disease.

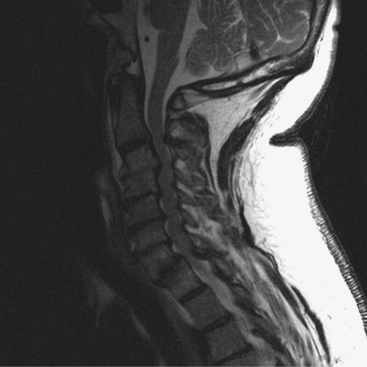

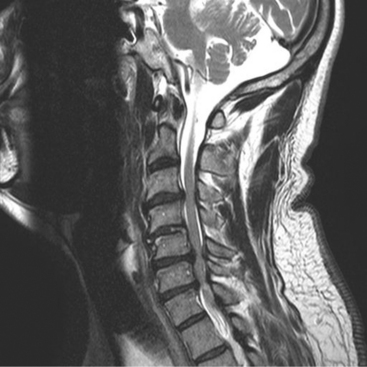

In general, primarily ventral pathology causing cord compression, particularly if it is focal rather than contiguous over multiple levels (Fig. 8-1), is best treated via an anterior approach.20 An anterior approach provides for direct visualization and removal of the offending pathologic lesion without manipulation of the cord. When a neutral or kyphotic cervical sagittal alignment is present, anterior procedures may also serve to restore physiologic lordosis. Restoration of lordosis allows for shifting of the cord dorsally to diminish the effect of anterior compression. After anterior decompression, spinal column stability is restored through segmental arthrodesis, which may have the added benefit of eliminating painful motion from the spondylotic motion segment.21 In contrast, if the compression is posterior and related primarily to facet hypertrophy or buckling ligamentum flavum, posterior decompression should be considered.9 However, the optimal surgical approach for the treatment of cervical myelopathy resulting from stenosis at three or more levels remains controversial. In addition to the earlier discussion, some other principles can assist in the selection of the appropriate approach, although an element of the surgeon’s preference will also be involved.22 An anterior arthrodesis of three or more motion segments is associated with a greater incidence of nonunion and graft-related problems than one- or two-level procedures.23–25 A posterior procedure, including laminectomy with or without fusion or laminoplasty, can achieve an indirect decompression and may be an excellent alternative to anterior decompression if the spine is lordotic21 (Fig. 8-2). If the spine is kyphotic, however, a posterior approach may be contraindicated because the spinal cord cannot displace dorsally from the anterior compressive structures, and a ventral approach is indicated. If the patient’s spine is straight, either procedure can be used.10

Other considerations include patient’s age and overall medical condition. Anterior surgery is more prolonged, and patients with multiple levels will be more likely to have dysphagia and voice problems after surgery; therefore, posterior surgery may be preferable if the alignment is not kyphotic for an older or a high medical risk patient.22

Although the optimal selection of surgical approach for CSM involving three or more motion segments in the presence of a lordotic sagittal alignment remains controversial (Fig. 8-3), few comparative studies are available. In 1985, one study compared the results of laminectomy versus corpectomy and anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) for the treatment of multilevel CSM, and demonstrated that multilevel corpectomy has a significantly greater rate of recovery and decreased late neurologic deterioration compared with laminectomy.26 These results disfavor laminectomy mainly because of the well-known sequelae, such as segmental instability, kyphosis, and perineural adhesions.27–36 In Japan, relatively poor outcomes associated with cervical laminectomy led to the evolution of laminoplasty, which remarkably reduced the sequelae after laminectomy.37–40 A radiographic analysis of cervical alignment after laminectomy and laminoplasty in humans demonstrated that segmental kyphosis was present in 33% of laminectomy patients and 6% of laminoplasty patients at an average of 6 years after surgery.41 A later study compared the results of laminoplasty with subtotal corpectomy42 and reported that there were no significant differences in either the maximum JOA recovery rate or the final recovery rate for the two procedures. However, a notable difference was the overall incidence rate of complications (29% for corpectomy and 7% for laminoplasty). A similar retrospective study43 showed that both procedures had similar rates of maintained neurologic improvement, and the disadvantages noted for the two procedures were pseudarthrosis (26%) and asymptomatic adjacent segment degeneration in a majority of patients after corpectomy, and decreased range of motion and axial discomfort (40%) after laminoplasty. A more recent prospective cohort study demonstrated that patients undergoing both procedures enjoyed a similar degree of subjective and objective neurologic improvement, but the incidence of complications was significantly greater for patients in the corpectomy cohort, especially persistent dysphagia and dysphonia.44 The authors conclude that laminoplasty may be the preferred method of treatment for multilevel cervical myelopathy in the absence of preoperative kyphosis. Another interesting observation of this study was that the laminoplasty cohort tended to require less pain medication at final follow-up than did the multilevel corpectomy cohort.44

Surgical indications of the combined approach to CSM are limited. A combined anterior and posterior approach may be considered for the following patients: (1) those with both anterior and posterior compression, which is difficult to treat with a single approach; (2) those with a loss of lordosis (either straightening or kyphosis) in addition to multilevel (three or more disc spaces) severe anterior compression from an osteocartilaginous spur or ossification of posterior longitudinal ligament (OPLL)45,46; or (3) those with severe osteoporosis, diabetes, or heavy nicotine use who have a poor rate of spinal fusion with ventral surgery alone.46 Some studies demonstrate that a single-stage combined procedure maximizes the decompression and reduces the graft-related surgical complications, as well as reducing perioperative complications when compared with staged combined procedures.45–47

ANTERIOR APPROACH

Anterior decompression and fusion has been widely applied to the treatment of cervical stenosis resulting from herniated discs, spondylosis, or OPLL. When the pathology occurs at the level of the intervertebral disc, ACDF provides sufficient access to the stenotic focus. Clinical studies have demonstrated that successful arthrodesis can be achieved in 92% to 96% of patients after single-level ACDF with satisfactory clinical results.21,48–50 Selection of surgical procedure (multilevel discectomy vs. cervical corpectomy) in multilevel pathology is controversial.51,52 Few studies directly compare multilevel ACDFs and corpectomy. In general, if compressive lesions are present at the level of the disc only, either a single-level or a multilevel ventral discectomy should be performed. However, if the lesion is behind the vertebral body, a corpectomy should be performed.

The advantage of performing a multilevel ACDF instead of a single-level or multilevel corpectomy and fusion is that with the multilevel discectomy, postdecompression segmental fixation can be achieved by placing screws into the intervening vertebral bodies. It is easier to restore sagittal balance after a multilevel ventral cervical discectomy as opposed to a cervical corpectomy by using this strategy.53 However, the disadvantage of multilevel ACDFs is that the incidence of nonunion increases with the number of levels being fused, although the rate of neurologic improvement remains high for multilevel ACDFs.54 The recently reported fusion rate for a one-level ACDF using autograft iliac crest without plating (two graft–host sites) was 96%.49 This decreased to a 75% fusion rate when a two-level ACDF was performed and to a 56% fusion rate with a three-level ACDF (six graft–host fusion sites).55

Corpectomy is an alternate option to improve the fusion rate after multilevel anterior decompression. Only two points must fuse in a corpectomy, as compared with multiple surfaces that must fuse with multilevel ACDFs. The additional advantage of a single-level or multilevel cervical corpectomy is the ability to decompress lesions behind the vertebral bodies.46 The studies that compared the fusion rate after multilevel ACDF and corpectomy reported the nonunion rate in corpectomy was 7% to 10% compared with 34% to 36% for patients undergoing multilevel ACDFs.23,25 Based on these factors, corpectomy may be considered preferable to multilevel ACDF, especially in higher-risk patients, such as smokers, patients with diabetes, or revision cases.21

The disadvantage of a cervical corpectomy is dislodgement of the graft, which often requires revision. Some reports have documented that the early strut dislocation rate was 8.7% to 21%.56–58 Various plate designs, including static plates, buttress plates, and more recently, dynamic plates, have been introduced to prevent anterior strut graft dislodgement and to decrease the rate of nonunion after corpectomy.59–61 However, early experience with static plating with multilevel corpectomies has shown that such plates might increase the incidence of strut graft dislodgement.24 Early designs of ventral cervical plates were not dynamic and shielded the bone graft from load bearing. Consequently, these designs did not exploit Wolff’s law, in which bone heals better when subjected to some loading stress to achieve subsequent fusion.46 Anterior cervical buttress plates were designed to prevent graft dislodgement whereas allowing for physiologic patterns of force application through the anterior column. However, failure at the implant–host bone interface and subsequent strut graft dislodgement were observed after multilevel corpectomy.62 Some studies have suggested additional posterior fusion to increase the rate of fusion and decrease the incidence of graft- and implant-related complication.46,63 A new generation of dynamic anterior plates has been developed to avoid the failures of static and buttress plates. These new plates resolved the stress-shielding problem by providing variable-angle screws, which allow for rotational pivoting at the screw–plate interface or interlocking sliding plates, which allow a certain degree of settling. As a result of this rotational pivoting or settling, these plates allow for increased loads to be placed on the disc space, thereby exploiting Wolff’s law to achieve fusion across the disc space or the corpectomy defect.64 However, no randomized clinical trials or even large matched-cohort studies are available to compare plated versus nonplated cervical corpectomy models. The role of these plates in a multilevel anterior decompression procedure remains inconclusive.

Autograft iliac crest has been widely used for anterior cervical surgery with an excellent fusion rate. However, reported patient morbidity rate with autograft iliac crest was greater than 20%, mainly because of donor site complications, including pain, hernia, and lateral femoral cutaneous nerve injury.65,66 In addition, limited bone stock and curved shape of the iliac crest are issues when replacing more than two levels with a corpectomy. Allograft is an alternative option to avoid these complicating factors of autograft. However, fusion rates with allograft are generally not as high as autograft. Multiple studies have compared the use of autograft and allograft, which have revealed that autograft is superior to allograft in terms of fusion rate,50,67–69 time to fuse,50 and graft collapse.50,67, 69 The introduction of the ventral cervical plate has made the use of allograft more appealing. Ventral cervical plates have decreased subsidence and improved fusion rates,55,70 which now approach the fusion rate of autograft in ACDF procedures.71

Titanium cages are another option for graft. They are readily available, there is no limitation in supply (unlike allograft and autograft), they avoid donor-site morbidity (unlike autograft), and they avoid the risk for infection from a donor cadaver (unlike allograft). When combined with ventral plate fixation, titanium cages perform well biomechanically in resisting flexion, extension, and lateral bending.72 Recent prospective, randomized studies comparing ACDF with autograft versus titanium cages have demonstrated that ACDF with titanium cage had a lower risk for complications, less requirement for graft harvest,73 and better clinical outcome of radiculopathy74 compared with autograft. Fusion rate,73 subsidence, and flexion deformity74 are not different between the two groups.

Cervical arthroplasty has recently become another alternative option for treatment of cervical degenerative disc disease (DDD). Cervical disc arthroplasty has the potential of maintaining anatomical disc space height, normal segmental lordosis, and physiologic motion patterns after surgery. These characteristics may reduce or delay the onset of DDD at adjacent cervical spinal motion segments after anterior cervical decompressive surgery,75–78 although conclusive evidence has yet to be shown. Compared with ACDF, prospective, randomized, clinical trials have demonstrated that cervical disc arthroplasty maintained physiologic segmental motion, improved clinical outcomes, and reduced rate of secondary surgeries.75,76, 79

POSTERIOR APPROACH

The posterior approach has been most commonly used for the management of cervical myelopathy involving three or more levels. The advantages of the posterior approach are to avoid the technical problems encountered with anterior cervical approach resulting from obesity, a short neck, barrel chest, anterior soft-tissue pathologic lesions, and a previous anterior surgery, as well as to avoid the potential for injury to the esophagus, trachea, and laryngeal nerves.21 Disadvantages of the posterior approach include iatrogenic cord or root trauma,80 nerve root dysfunction (especially C5 nerve root),30,40,81–84 late neurologic deterioration associated with kyphotic deformity,26,85 and axial symptoms, such as neck pain, stiffness, fatigue, or shoulder discomfort.86

Historically, laminectomy has been regarded as the standard posterior procedure for the treatment of multilevel CSM with satisfactory results in a high percentage of patients.34,35, 41, 87 However, significant problems were associated with postlaminectomy segmental instability and kyphosis secondary to iatrogenic destabilization of the cervical spine. Also, development of a scar membrane around the dura can cause neurologic worsening in a subset of patients.34,35, 41, 87 Some studies have shown that resection of greater than 50% of the facet joint significantly compromises facet strength88 and results in segmental hypermobility,50 whereas biomechanically, as little as a 25% facetectomy affects stability after multilevel laminectomy.89 Another biomechanical study demonstrated that 36% of load transmission was through the anterior (vertebral bodies) columns, whereas 64% was through the posterior columns.90 Therefore, the posterior neural arch is responsible for most of the load transmission in the cervical spine, and significant loss of integrity of this posterior arch-facet complex can result in instability, causing the weight-bearing axis to shift anteriorly.91 Kyphosis progresses subsequent to this loss of sagittal balance, which places the cervical musculature at a mechanical disadvantage, requiring constant contractions to maintain upright head posture. This progression causes most of the weight to be borne by the discs and anterior vertebral bodies, which may lead to further degeneration and spondylosis.92,93

The addition of posterior cervical fusion with instrumentation is an option that attempts to avoid the development of a postlaminectomy kyphotic deformity.93–96 Fusion also allows for a more extensive laminectomy and foraminotomy without jeopardizing stability. Recently, lateral mass fixation, involving fixation of a small plate or rod to the lateral masses with screws, has been widely applied.57,97–101 These devices provide superb flexural stability and resist torsion and extension significantly better than spinous process wiring.102 The enhanced stability can decrease or eliminate the need for a postoperative orthosis. Disadvantages of these procedures include nonunion, hardware failure, adjacent segment degeneration, high cost, and potential injury to the nerve root and vertebral artery.103,104

Laminoplasty, which was developed in Japan in the late 1970s39 with numerous modification since that time,38,105–108 is another valid option to avoid the development of a postlaminectomy kyphosis. This procedure, by leaving the dorsal stabilizing structures in situ, is thought to mitigate the development of kyphosis and, with subsequent bone fusion, to stabilize the cervical spine with an improved outcome.109 However, laminoplasty performed on patients with cervical kyphosis has resulted in less vertebral canal enlargement and functional recovery than those patients with a lordotic alignment. Additional factors associated with inferior outcomes are cord atrophy, long duration of symptoms, advanced age, severe cord compression, and radiculopathy.110,111 Laminoplasty is not considered a fusion procedure. However, most patients experience a significant loss of subaxial motion after the procedure and some do go on to fusion.112

Few prospective comparative studies between the procedures available exist. A study comparing laminectomy and laminoplasty has demonstrated that patients with both procedures improved in gait, strength, sensation, pain, and degree of myelopathy. However, laminoplasty was associated with fewer late complications.113 Another matched cohort study of laminoplasty and laminectomy with fusion demonstrated that laminoplasty was favorable because of less procedural complications, although patients in both groups showed no statistical difference in improvement of strength, dexterity, sensation, pain, and gait.103 The high complication rate (9/13 patients) in the laminectomy fusion group, included instrumentation failure, nonunion, and development of myelopathy. In contrast, the laminoplasty group had no complications. This may be biased because of the surgeon’s procedural familiarity with laminoplasty, rather than laminectomy with fusion.

RECOMMENDATIONS

| Summary of Recommendations | ||

|---|---|---|

| STATEMENT | LEVEL OF EVIDENCE/GRADE OF RECOMMENDATION | REFERENCES |

1 Young WF. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: A common cause of spinal cord dysfunction in older persons. Am Fam Physician. 2000;62:1064-1073.

2 Clarke E, Robinson PK. Cervical myelopathy: A complication of cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1956;79:483-510.

3 Spillane JD, Lloyd GH. The diagnosis of lesions of the spinal cord in association with ‘osteoarhritic’ disease of the cervical spine. Brain. 1952;75:177-186.

4 Symon L, Lavender P. The surgical treatment of cervical spondylitic myelopathy. Neurology. 1967;17:117-127.

5 Lees F, Turner JW. Natural history and prognosis of cervical spondylosis. Br Med J. 1963;2:1607-1610.

6 Roberts AH. Myelopathy due to cervical spondylosis treated by collar immobilization. Neurology. 1966;16:951-954.

7 Nurick S. The pathogenesis of the spinal cord disorder associated with cervical spondylosis. Brain. 1972;95:87-100.

8 Rao R. Neck pain, cervical radiculopathy, and cervical myelopathy: Pathophysiology, natural history, and clinical evaluation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 2002;84:1872-1881.

9 Epstein JA, Epstein NE. The surgical management of cervical spinal stenosis, spondylosis, and myeloradiculopathy by means of the posterior approach. In: Sherk HH, Dunn EJ, Eismont FJ, et al, editors. The Cervical Spine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1989:625-643.

10 McCormick WE, Steinmetz MP, Benzel EC. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Make the difficult diagnosis, then refer for surgery. Cleve Clin J Med. 2003;70:899-904.

11 Firooznia H, Ahn JH, Rafii M, Ragnarsson KT. Sudden quadriplegia after a minor trauma: The role of preexisting spinal stenosis. Surg Neurol. 1985;23:165-168.

12 Sampath P, Bendebba M, Davis JD, Ducker TB. Outcome of patients treated for cervical myelopathy: A prospective multicenter study with independent clinical review. Spine. 2000;25:670-676.

13 Fouyas IP, Statham PF, Sandercock PA. Cochrane review on the role of surgery in cervical spondylotic radiculomyelopathy. Spine. 2002;27:736-747.

14 Kadanka Z, Mares M, Bednanik J, et al. Approaches to spondylotic cervical myelopathy: Conservative versus surgical results in a 3-year follow-up study. Spine. 2002;27:2205-2210.

15 Kadanka Z, Mares M, Bednarik J, et al. Predictive factors for spondylotic cervical myelopathy treated conservatively or surgically. Eur J Neurol. 2005;12:55-63.

16 Emery SE. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Diagnosis and treatment. J Am Acad Orthop Surg. 2001;9:376-388.

17 Bednarik J, Kadanka Z, Dusek L, et al. Presymptomatic spondylotic cervical cord compression. Spine. 2004;29:2260-2269.

18 Yoshimatsu H, Nagata K, Goto H, et al. Conservative treatment for cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Prediction of treatment effects by multivariate analysis. Spine J. 2001;1:269-273.

19 Boden SD, McCowin PR, Davis DO. Abnormal magnetic-resonance scans of the cervical spine in asymptomatic subjects: A prospective investigation. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1990;72:1178-1184.

20 Matz PG, Pritchard PR, Hadley MN. Anterior cervical approach for the treatment of cervical myelopathy. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(supp1 1):S64-S70.

21 Edwards CC2nd, Riew KD, Anderson PA, et al. Cervical myelopathy. Current diagnostic and treatment strategies. Spine J. 2003;3:68-81.

22 Hillard VH, Apfelbaum RI. Surgical management of cervical myelopathy: Indications and techniques for multilevel cervical discectomy. Spine J.; 6 suppl; 2006; 242S-251S.

23 Swank M, Lowery G, Bhat A. Improved arthrodesis with strut-grafting and instrumentation: Multi-level interbody grafting or strut graft reconstruction. Eur Spine J. 1997;6:138-143.

24 Vaccaro AR, Falatyn SP, Scuderi GJ. Early failure of long segment anterior cervical plate fixation. J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:410-415.

25 Hilibrand A, Fye M, Emery S. Improved arthrodesis with strut-grafting after multi-level anterior cervical decompression. Spine. 2002;27:146-151.

26 Yonenobu K, Fuji T, Ono K, et al. Choice of surgical treatment for multisegmental cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 1985;10:710-716.

27 Butler JC, Whitecloud TSIII. Postlaminectomy kyphosis: Causes and surgical management. Orthop Clin North Am. 1992;23:505-511.

28 Cerisoli M, Vernizzi E, Guilioni M. Cervical spine changes following laminectomy: Clinico-radiological study. J Neurosurg Sci. 1980;24:63-70.

29 Crandall PH, Gregorious FK. Long-term follow-up of surgical treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 1977;2:139-146.

30 Dai L, Ni B, Yuan W, Jia L. Radiculopathy after laminectomy for cervical compression myelopathy. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 1998;80:846-849.

31 Guigui P, Lefevre C, Lassale B, Deburge A. Static, dynamic changes of the cervical spine after laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Rev Chir Orthop Reparatrice Appar Mot. 1998;84:17-25.

32 Ishida Y, Suzuki K, Ohmori K, et al. Critical analysis of extensive cervical laminectomy. Neurosurgery. 1989;24:215-222.

33 Lonstein JE. Post-laminectomy kyphosis. Clin Orthop. 1977;128:93-100.

34 Mikawa Y, Shikata J, Yamamuro T. Spinal deformity and instability after multilevel cervical laminectomy. Spine. 1987;12:6-11.

35 Morimoto T, Okuno S, Nakase H, et al. Cervical myelopathy due to dynamic compression by the laminectomy membrane: Dynamic MR imaging study. J Spinal Disord. 1999;12:172-173.

36 Sim FH, Suien HJ, Bickel WH, Janes JM. Swan neck deformity following extensive cervical laminectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1974;56:564-580.

37 Hirabayashi K. Expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myelopathy [in Japanese]. Jpn J Surg. 1978;32:1159-1163.

38 Kurokawa T, Tsuyama N, Tanaka H, et al. Enlargement of spinal canal by the sagittal splitting of the spinous process. Bessatsu Seikei Geka. 1982;2:234-240.

39 Oyama M, Hattori S, Moriwaki N. A new method of posterior decompression [in Japanese]. Cent Jpn J Orthop Traumat Surg. 1973;16:792-794.

40 Tomita K, Kawahara N, Toribatake Y, Heller JG. Expansive midline T-saw laminoplasty (modified spinous process-splitting) for the management of cervical myelopathy. Spine. 1998;23:32-37.

41 Matsunaga S, Sakou T, Nakansisi K. Analysis of the cervical spine alignment following laminoplasty and laminectomy. Spinal Cord. 1999;37:20-24.

42 Yonenobu H, Hosono N, Iwasaki M, et al. Laminoplasty versus subtotal corpectomy: A comparative study of results in multisegmental cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 1992;17:1281-1284.

43 Wada E, Suzuki S, Kanazawa A. Subtotal corpectomy versus laminoplasty for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy: A long-term follow-up study of over 10 years. Spine. 2001;26:1443-1447.

44 Edwards CC2nd, Heller JG, Murakami H. Corpectomy versus laminoplasty for multilevel cervical myelopathy: An independent matched-cohort analysis. Spine. 2002;27:1168-1175.

45 Schultz KDJr, McLaughlin MR, Haid RWJr, et al. Single-stage anterior-posterior decompression and stabilization for complex cervical spine disorders. J Neurosurg. 2000;93(2 suppl):214-221.

46 Mummaneni PV, Haid RW, Rodts GEJr. Combined ventral and dorsal surgery for myelopathy and myeloradiculopathy. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(1 supp1 1):S82-S89.

47 McAfee PC, Bohlman HH, Ducker TB, et al. One-stage anterior cervical decompression and posterior stabilization. A study of one hundred patients with a minimum of two years of follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1995;77:1791-1800.

48 Bosacco D, Berman A, Levenberg R. Surgical results in anterior cervical discectomy and fusion using a countersunk interlocking autogenous iliac bone graft. Orthopedics. 1992;15:923-925.

49 Emery SE, Bolesta MJ, Banks MA, Jones PK. Robinson anterior cervical fusion—comparison of the standard and modified techniques. Spine. 1994;19:660-663.

50 Zdeblick TA, Ducker TB. The use of freeze-dried allograft bone for anterior cervical fusions. Spine. 1991;16:726-729.

51 Barnes B, Haid RW, Rodts GE Jr: Multilevel ACDF vs. corpectomy: Significantly better outcomes with corpectomy at 19 month follow-up. Platform presentation at the Congress of Neurological Surgeons Annual Meeting, October 2002, Philadelphia.

52 Emery SE, Bohlman HH, Bolesta MJ, Jones PK. Anterior cervical decompression and arthrodesis for the treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Two to seventeen-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1998;80:941-951.

53 Kaiser MG, Haid RWJr, Subach BR, et al. Anterior cervical plating enhances arthrodesis after discectomy and fusion with cortical allograft. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:229-238.

54 Zhang Z, Yin H, Yang K. Anterior intervertebral disc excision and bone grafting in cervical spondylotic myelopathy. Spine. 1983;5:16-19.

55 Wang JC, McDonough PW, Endow KK, Delamarter RB. Increased fusion rates with cervical plating for two-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion. Spine. 2000;25:41-45.

56 Whitecloud TS, LaRocca H. Fibular strut graft in reconstructive surgery of the cervical spine. Spine. 1976;1:33-43.

57 Zdeblick TA, Bohlman HH. Cervical kyphosis and myelopathy. Treatment by anterior corpectomy and strut-grafting. J Bone Joint Surg Am. 1989;71:170-182.

58 Macdonald RL, Fehlings MG, Tator CH, et al. Multilevel anterior cervical corpectomy and fibular allograft fusion for cervical myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:990-997.

59 An HS, Gordin R, Renner K. Anatomic considerations for plate-screw fixation of the cervical spine. Spine. 1991;16:548-551.

60 Grubb MR, Currier BL, Shih JS. Biomechanical evaluation of anterior cervical spine stabilization. Spine. 1998;15:886-892.

61 Katsuura A, Hakuda S, Imanaka T, et al. Anterior cervical plate used in degenerative disease can maintain cervical lordosis. J Spinal Dis. 1996;9:470-476.

62 Riew KD, Sethi NS, Devney J, et al. Complications of buttress plate stabilization of cervical corpectomy. Spine. 1999;24:2404-2410.

63 Epstein N. Anterior cervical discectomy and fusion without plate instrumentation in 178 patients. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:1-8.

64 Mummaneni PV, Srinivasan JK, Haid RW, Mizuno J. Overview of anterior cervical plating. Spinal Surg. 2002;16:207-216.

65 Heary RF, Schlenk RP, Sacchieri TA, et al. Persistent iliac crest donor site pain: Independent outcome assessment. Neurosurgery. 2002;50:510-517.

66 Sasso RC, Ruggiero RAJr, Reilly TM, Hall PV. Early reconstruction failures after multi-level cervical corpectomy. Spine. 2003;28:140-142.

67 An HS, Simpson JM, Glover JM, Stephany J. Comparison between allograft plus demineralized bone matrix versus autograft in anterior cervical fusion: A prospective multicenter study. Spine. 1995;20:2211-2216.

68 Bishop RC, Moore KA, Hadley MN. Anterior cervical interbody fusion using autogenic and allogenic bone graft substrate: A prospective comparative analysis. J Neurosurg. 1996;85:206-210.

69 Floyd T, Ohnmeiss D. A meta-analysis of autograft versus allograft in anterior cervical fusion. Eur Spine J. 2000;9:398-403.

70 Caspar W, Geisler FH, Pitzen T, Johnson TA. Anterior cervical plate stabilization in one- and two-level degenerative disease: Overtreatment or benefit? J Spinal Disord. 1998;11:1-11.

71 Deutsch H, Haid R, Rodts GJr, Mummaneni PV. The decision-making process: Allograft versus autograft. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(suppl):S98-S102.

72 Kandziora F, Pflugmacher R, Schafer J, et al. Biomechanical comparison of cervical spine interbody fusion cages. Spine. 2001;26:1850-1857.

73 Hacker RJ, Cauthen JC, Gilbert TJ, Griffith SL. A prospective randomized multicenter clinical evaluation of an anterior cervical fusion cage. Spine. 2000;25:2646-2654.

74 Lind BI, Zoega B, Rosen H. Autograft versus interbody fusion cage without plate fixation in the cervical spine: A randomized clinical study using radiostereometry. Eur Spine J. 2007;16:1251-1256.

75 Cummins BH, Robertson JT, Gill SS. Surgical experience with an implanted artificial cervical joint. J Neurosurg. 1998;88:943-948.

76 Goffin J, Van Calenbergh F, van Loon J, et al. Intermediate follow-up after treatment of degenerative disc disease by the Bryan Cervical Disc Prosthesis: Single-level and bi-level. Spine. 2003;28:2673-2678.

77 Mummaneni PV, Haid RW. The future in the care of the cervical spine: Interbody fusion and arthroplasty. J Neurosurg Spine. 2004;1:155-159.

78 Wigfield CC, Gill S, Nelson R, et al. Influence of an artificial cervical joint compared with fusion on adjacent-level motion in the treatment of degenerative cervical disc disease. J Neurosurg. 2002;96(1 suppl):17-21.

79 Goffin J, Casey A, Kehr P, et al. Preliminary clinical experience with the Bryan Cervical Disc prosthesis. Neurosurgery. 2002;51:840-847.

80 Kirita Y. Posterior decompression or the cervical spondylosis and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament in the cervical spine [in Japanese]. Surgery. 1976;30:287-302.

81 Kawaguchi Y, Kanamori M, Hirokazu I: Minimum 10-year followup after en block cervical laminoplasty. Presented at the Cervical Spine Research Society, November 30, 2000 to December 2, 2000, Charleston, SC.

82 Yonenobu K, Yamamoto T, Ono K: Laminoplasty for myelopathy: Indications, results, outcome and complications. In Clark (ed): The Cervical Spine, 3rd ed. Philadelphia, 1998, pp 849–864.

83 Yonenobu K, Hosono N, Iwasaki M, et al. Neurologic complications of surgery for cervical compression myelopathy. Spine. 1991;16:1277-1282.

84 Dante SJ, Heary R, Kramer D. Cervical laminectomy for myelopathy. Oper Techn Orthop. 1996;6:30-37.

85 Kaptain GJ, Simmons NE, Replogle RE, et al. Incidence and outcome of kyphotic deformity following laminectomy for cervical spondylotic myelopathy. J Neurosurg. 2000;93:1999-2004.

86 Hosono N, Yonenobu K, Ono K. Neck and shoulder pain after laminoplasty: A noticeable complication. Spine. 1996;21:1969-1973.

87 Snow RB, Weiner H. Cervical laminectomy and foraminotomy as surgical treatment of cervical spondylosis: A follow-up study with analysis of failures. J Spinal Disord. 1993;6:245-250.

88 Raynor RB, Pugh J, Shapiro I. Cervical facetectomy and its effect on spine strength. J Neurosurg. 1995;63:278-282.

89 Nowinski GP, Visarius H, Nolte LP, et al. A biomechanical comparison of cervical laminoplasty and cervical laminectomy with progressive facetectomy. Spine. 1993;18:1995-2004.

90 Pal PP, Cooper HH. The vertical stability of the cervical spine. Spine. 1988;13:447-449.

91 Raynor RB, Moskovich R, Zidel P, Pugh J. Alterations in primary and coupled neck motions after facetectomy. Neurosurgery. 1987;21:681-687.

92 Albert TJ, Vacarro A. Postlaminectomy kyphosis. Spine. 1998;23:2738-2745.

93 Houten JK, Cooper PR. Laminectomy and posterior cervical plating for multilevel cervical spondylotic myelopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament: Effects on cervical alignment, spinal cord compression, and neurological outcome. Neurosurgery. 2003;52:1081-1088.

94 Kumar VG, Rea GL, Mervis LJ, et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy—functional and radiographic long-term outcome after laminectomy and posterior fusion. Neurosurgery. 1999;44:771-777.

95 Miyazaki K, Hirohuji E, Ono S. Extensive simultaneous multi-segmental laminectomy and posterior decompression with posterolateral fusion. J Jpn Res Soc. 1994;5:167.

96 Maurer PK, Ellenbogen RG, Eckland J, et al. Cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Treatment with posterior decompression and Luque rectangle bone fusion. Neurosurgery. 1991;28:680-683.

97 Cherney WB, Sonntag VK, Douglas RA. Lateral mass posterior plating and facet fusion for cervical spine instability. Barrow Neurol Inst Q. 1991;7:2-11.

98 Cooper PR, Cohen A, Rosiello A, Koslow M. Posterior stabilization of cervical spine fractures and subluxations using plates and screws. Neurosurgery. 1988;23:300-306.

99 Magerl F, Grob D, Seemann P. Stable dorsal fusion of the cervical spine (C2-Th1) using hook plates. Kehr P, Weidner A, editors. Cervical Spine.; vol 1; 1987; Springer-Verlag: New York; 217-221.

100 Roy-Camille R, Saillant G, Mazel C. Internal fixation of the unstable cervical spine by a posterior osteosynthesis with plates and screws. In: Cervical Spine Research Society, editor. The Cervical Spine. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1989:390-403.

101 Weidner A. Internal fixation with metal plates and screws. In: Cervical Spine Research Society, editor. The Cervical Spine. 2nd ed. Philadelphia: JB Lippincott; 1989:404-421.

102 Sato T. Radiological follow-up of motion in the cervical spine after surgery [in Japanese]. Nippon Seikeigeka Gakkai Zasshi. 1992;66:607-620.

103 Heller JG, Edwards CC2nd, Murakami H, Rodts GE. Laminoplasty versus laminectomy and fusion for multilevel cervical myelopathy: An independent matched cohort analysis. Spine. 2001;26:1330-1336.

104 Wellman BJ, Follett KA, Traynelis VC. Complications of posterior articular mass plate fixation of the subaxial cervical spine in 43 consecutive patients. Spine. 1998;23:193-200.

105 Hirabayashi K, Watanabe K, Wakano K, et al. Expansive open-door laminoplasty for cervical spinal stenotic myelopathy. Spine. 1983;8:693-699.

106 Kokubun S, Sato T, Ishii Y, Tanaka Y. Cervical myelopathy in the Japanese. Clin Orthop Relat Res. 1996;323:129-138.

107 Nakano N, Nakano T, Nakano K. Comparison of the results of laminectomy and open-door laminoplasty for cervical spondylotic myeloradiculopathy and ossification of the posterior longitudinal ligament. Spine. 1988;13:792-794.

108 Tsuji H. Laminoplasty for patients with compressive myelopathy due to so-called spinal canal stenosis in cervical and thoracic regions. Spine. 1982;7:28-34.

109 Vitarbo E, Sheth RN, Levi AD. Open-door expansile cervical laminoplasty. Neurosurgery. 2007;60(suppl 1):S154-S159.

110 Kohno K, Kumon Y, Oka Y. Evaluation of prognostic factors following expansive laminoplasty for cervical spinal stenotic myelopathy. Surg Neurol. 1997;48:237-245.

111 Lee TT, Manzano GR, Green BA. Modified open-door cervical expansive laminoplasty for spondylotic myelopathy: Operative technique, outcome and predictors of gait improvement. J Neurosurg. 1997;86:64-68.

112 Edwards CC, Heller JG, Silcox DH. “T-saw” laminoplasty for the management of cervical spondylotic myelopathy: Clinical and radiographic outcome. Spine. 2000;25:1788-1794.

113 Kaminsky SB, Clark CR, Traynelis VC. Operative treatment of cervical spondylotic myelopathy and radiculopathy. A comparison of laminectomy and laminoplasty at five year average follow-up. Iowa Orthop J. 2004;24:95-105.